Dynamic programming

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In mathematics and computer science, dynamic programming is a method of solving problems that exhibit the properties of overlapping subproblems and optimal substructure (described below). The method takes much less time than naive methods.

The term was originally used in the 1940s by Richard Bellman to describe the process of solving problems where one needs to find the best decisions one after another. By 1953, he had refined this to the modern meaning.[1] The field was founded as a systems analysis and engineering topic that is recognized by the IEEE. Bellman's contribution is remembered in the name of the Bellman equation, a central result of dynamic programming which restates an optimization problem in recursive form.

The word "programming" in "dynamic programming" has no particular connection to computer programming at all, and instead comes from the term "mathematical programming", a synonym for optimization. Thus, the "program" is the optimal plan for action that is produced. For instance, a finalized schedule of events at an exhibition is sometimes called a program. Programming, in this sense, means finding an acceptable plan of action, an algorithm.

Contents |

[edit] Overview

Optimal substructure means that optimal solutions of subproblems can be used to find the optimal solutions of the overall problem. For example, the shortest path to a goal from a vertex in a graph can be found by first computing the shortest path to the goal from all adjacent vertices, and then using this to pick the best overall path, as shown in Figure 1. In general, we can solve a problem with optimal substructure using a three-step process:

- Break the problem into smaller subproblems.

- Solve these problems optimally using this three-step process recursively.

- Use these optimal solutions to construct an optimal solution for the original problem.

The subproblems are, themselves, solved by dividing them into sub-subproblems, and so on, until we reach some simple case that is solvable in constant time.

To say that a problem has overlapping subproblems is to say that the same subproblems are used to solve many different larger problems. For example, in the Fibonacci sequence, F3 = F1 + F2 and F4 = F2 + F3 — computing each number involves computing F2. Because both F3 and F4 are needed to compute F5, a naive approach to computing F5 may end up computing F2 twice or more. This applies whenever overlapping subproblems are present: a naive approach may waste time recomputing optimal solutions to subproblems it has already solved.

In order to avoid this, we instead save the solutions to problems we have already solved. Then, if we need to solve the same problem later, we can retrieve and reuse our already-computed solution. This approach is called memoization (not memorization, although this term also fits). If we are sure we won't need a particular solution anymore, we can throw it away to save space. In some cases, we can even compute the solutions to subproblems we know that we'll need in advance.

In summary, dynamic programming makes use of:

Dynamic programming usually takes one of two approaches:

- Top-down approach: The problem is broken into subproblems, and these subproblems are solved and the solutions remembered, in case they need to be solved again. This is recursion and memoization combined together.

- Bottom-up approach: All subproblems that might be needed are solved in advance and then used to build up solutions to larger problems. This approach is slightly better in stack space and number of function calls, but it is sometimes not intuitive to figure out all the subproblems needed for solving the given problem.

Some programming languages can automatically memoize the result of a function call with a particular set of arguments, in order to speed up call-by-name evaluation (this mechanism is referred to as call-by-need). Some languages make it possible portably (e.g. Scheme, Common Lisp or Perl), some need special extensions (e.g. C++, see [2]). Some languages have automatic memoization built in. In any case, this is only possible for a referentially transparent function.

[edit] Examples

[edit] Fibonacci sequence

A naive implementation of a function finding the nth member of the Fibonacci sequence, based directly on the mathematical definition:

function fib(n)

if n = 0 return 0

if n = 1 return 1

return fib(n − 1) + fib(n − 2)

Notice that if we call, say, fib(5), we produce a call tree that calls the function on the same value many different times:

fib(5)fib(4) + fib(3)(fib(3) + fib(2)) + (fib(2) + fib(1))((fib(2) + fib(1)) + (fib(1) + fib(0))) + ((fib(1) + fib(0)) + fib(1))(((fib(1) + fib(0)) + fib(1)) + (fib(1) + fib(0))) + ((fib(1) + fib(0)) + fib(1))

In particular, fib(2) was calculated three times from scratch. In larger examples, many more values of fib, or subproblems, are recalculated, leading to an exponential time algorithm.

Now, suppose we have a simple map object, m, which maps each value of fib that has already been calculated to its result, and we modify our function to use it and update it. The resulting function requires only O(n) time instead of exponential time:

var m := map(0 → 0, 1 → 1)

function fib(n)

if map m does not contain key n

m[n] := fib(n − 1) + fib(n − 2)

return m[n]

This technique of saving values that have already been calculated is called memoization; this is the top-down approach, since we first break the problem into subproblems and then calculate and store values.

In the bottom-up approach we calculate the smaller values of fib first, then build larger values from them. This method also uses linear (O(n)) time since it contains a loop that repeats n − 1 times, however it only takes constant (O(1)) space, in contrast to the top-down approach which requires O(n) space to store the map.

function fib(n)

var previousFib := 0, currentFib := 1

if n = 0

return 0

else if n = 1

return 1

repeat n − 1 times

var newFib := previousFib + currentFib

previousFib := currentFib

currentFib := newFib

return currentFib

In both these examples, we only calculate fib(2) one time, and then use it to calculate both fib(4) and fib(3), instead of computing it every time either of them is evaluated.

[edit] A type of balanced 0-1 matrix

Consider the problem of assigning values, either zero or one, to the positions of an n x n matrix, n even, so that each row and each column contains exactly n/2 zeros and n/2 ones. For example, when n = 4, three possible solutions are

+ - - - - + + - - - - + + - - - - + | 0 1 0 1 | | 0 0 1 1 | | 1 1 0 0 | | 1 0 1 0 | and | 0 0 1 1 | and | 0 0 1 1 | | 0 1 0 1 | | 1 1 0 0 | | 1 1 0 0 | | 1 0 1 0 | | 1 1 0 0 | | 0 0 1 1 | + - - - - + + - - - - + + - - - - +

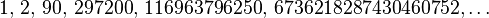

We ask how many different assignments there are for a given n. There are at least three possible approaches: brute force, backtracking and dynamic programming. Brute force consists of checking all assignments of zeros and ones and counting those that have balanced rows and columns (n/2 zeros and n/2 ones). As there are  possible assignments, this strategy is not practicable except maybe up to n = 6. Backtracking for this problem consists of choosing some order of the matrix elements and recursively placing ones or zeros, while checking that in every row and column the number of elements that have not been assigned plus the number of ones or zeros are both at least n/2. While more sophisticated than brute force, this approach will visit every solution once, making it impracticable for n larger than six, since the number of solutions is already 116963796250 for n=8, as we shall see. Dynamic programming makes it possible to count the number of solutions without visiting them all.

possible assignments, this strategy is not practicable except maybe up to n = 6. Backtracking for this problem consists of choosing some order of the matrix elements and recursively placing ones or zeros, while checking that in every row and column the number of elements that have not been assigned plus the number of ones or zeros are both at least n/2. While more sophisticated than brute force, this approach will visit every solution once, making it impracticable for n larger than six, since the number of solutions is already 116963796250 for n=8, as we shall see. Dynamic programming makes it possible to count the number of solutions without visiting them all.

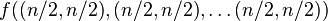

We consider  boards, where 1 < = k < = n whose k rows contain n / 2 zeros and n / 2 ones. The function f to which memoization is applied maps vectors of n pairs of integers to the number of admissible boards (solutions). There is one pair for each column and its two components indicate respectively the number of ones and zeros that have yet to be placed in that column. We seek the value of

boards, where 1 < = k < = n whose k rows contain n / 2 zeros and n / 2 ones. The function f to which memoization is applied maps vectors of n pairs of integers to the number of admissible boards (solutions). There is one pair for each column and its two components indicate respectively the number of ones and zeros that have yet to be placed in that column. We seek the value of  (n arguments or one vector of n elements). The process of subproblem creation involves iterating over every one of

(n arguments or one vector of n elements). The process of subproblem creation involves iterating over every one of  possible assignments for the top row of the board, and going through every column, subtracting one from the appropriate element of the pair for that column, depending on whether the assignment for the top row contained a zero or a one at that position. If any one of the results is negative, then the assignment is invalid and does not contribute to the set of solutions (recursion stops). Otherwise, we have an assignment for the top row of the

possible assignments for the top row of the board, and going through every column, subtracting one from the appropriate element of the pair for that column, depending on whether the assignment for the top row contained a zero or a one at that position. If any one of the results is negative, then the assignment is invalid and does not contribute to the set of solutions (recursion stops). Otherwise, we have an assignment for the top row of the  board and recursively compute the number of solutions to the remaining

board and recursively compute the number of solutions to the remaining  board, adding the numbers of solutions for every admissible assignment of the top row and returning the sum, which is being memoized. The base case is the trivial subproblem, which occurs for a

board, adding the numbers of solutions for every admissible assignment of the top row and returning the sum, which is being memoized. The base case is the trivial subproblem, which occurs for a  board. The number of solutions for this board is either zero or one, depending on whether the vector is a permutation of n/2 (0, 1) and n/2 (1, 0) pairs or not.

board. The number of solutions for this board is either zero or one, depending on whether the vector is a permutation of n/2 (0, 1) and n/2 (1, 0) pairs or not.

For example, in the two boards shown above the sequences of vectors would be

((2, 2) (2, 2) (2, 2) (2, 2)) ((2, 2) (2, 2) (2, 2) (2, 2)) k = 4 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 ((1, 2) (2, 1) (1, 2) (2, 1)) ((1, 2) (1, 2) (2, 1) (2, 1)) k = 3 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 ((1, 1) (1, 1) (1, 1) (1, 1)) ((0, 2) (0, 2) (2, 0) (2, 0)) k = 2 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 ((0, 1) (1, 0) (0, 1) (1, 0)) ((0, 1) (0, 1) (1, 0) (1, 0)) k = 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 ((0, 0) (0, 0) (0, 0) (0, 0)) ((0, 0) (0, 0), (0, 0) (0, 0))

The number of solutions (sequence A058527 in OEIS) is

Links to the Perl source of the backtracking approach, as well as a MAPLE and a C implementation of the dynamic programming approach may be found among the external links.

[edit] Checkerboard

Consider a checkerboard with n × n squares and a cost-function c(i, j) which returns a cost associated with square i,j (i being the row, j being the column). For instance (on a 5 × 5 checkerboard),

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 2 |

| 2 | - | 6 | 7 | 0 | - |

| 1 | - | - | 5* | - | - |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Thus c(1, 3) = 5

Let us say you had a checker that could start at any square on the first rank (i.e., row) and you wanted to know the shortest path (sum of the costs of the visited squares are at a minimum) to get to the last rank, assuming the checker could move only diagonally left forward, diagonally right forward, or straight forward. That is, a checker on (1,3) can move to (2,2), (2,3) or (2,4).

| 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | |||||

| 3 | |||||

| 2 | x | x | x | ||

| 1 | o | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

This problem exhibits optimal substructure. That is, the solution to the entire problem relies on solutions to subproblems. Let us define a function q(i, j) as

- q(i, j) = the minimum cost to reach square (i, j)

If we can find the values of this function for all the squares at rank n, we pick the minimum and follow that path backwards to get the shortest path.

Note that q(i, j) is equal to the minimum cost to get to any of the three squares below it (since those are the only squares that can reach it) plus c(i, j). For instance:

| 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | A | ||||

| 3 | B | C | D | ||

| 2 | |||||

| 1 | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Now, let us define q(i, j) in somewhat more general terms:

The first line of this equation is there to make the recursive property simpler (when dealing with the edges, so we need only one recursion). The second line says what happens in the last rank, to provide a base case. The third line, the recursion, is the important part. It is similar to the A,B,C,D example. From this definition we can make a straightforward recursive code for q(i, j). In the following pseudocode, n is the size of the board, c(i, j) is the cost-function, and min() returns the minimum of a number of values:

function minCost(i, j)

if j < 1 or j > n

return infinity

else if i = 5

return c(i, j)

else

return min( minCost(i+1, j-1), minCost(i+1, j), minCost(i+1, j+1) ) + c(i, j)

It should be noted that this function only computes the path-cost, not the actual path. We will get to the path soon. This, like the Fibonacci-numbers example, is horribly slow since it spends mountains of time recomputing the same shortest paths over and over. However, we can compute it much faster in a bottom-up fashion if we use a two-dimensional array q[i, j] instead of a function. Why do we do that? Simply because when using a function we recompute the same path over and over, and we can choose what values to compute first.

We also need to know what the actual path is. The path problem we can solve using another array p[i, j], a predecessor array. This array basically says where paths come from. Consider the following code:

function computeShortestPathArrays()

for x from 1 to n

q[1, x] := c(1, x)

for y from 1 to n

q[y, 0] := infinity

q[y, n + 1] := infinity

for y from 2 to n

for x from 1 to n

m := min(q[y-1, x-1], q[y-1, x], q[y-1, x+1])

q[y, x] := m + c(y, x)

if m = q[y-1, x-1]

p[y, x] := -1

else if m = q[y-1, x]

p[y, x] := 0

else

p[y, x] := 1

Now the rest is a simple matter of finding the minimum and printing it.

function computeShortestPath()

computeShortestPathArrays()

minIndex := 1

min := q[n, 1]

for i from 2 to n

if q[n, i] < min

minIndex := i

min := q[n, i]

printPath(n, minIndex)

function printPath(y, x)

print(x)

print("<-")

if y = 2

print(x + p[y, x])

else

printPath(y-1, x + p[y, x])

[edit] Sequence alignment

Sequence alignment is an important application where dynamic programming is essential. Typically, the problem consists of transforming one sequence into another using edit operations that replace, insert, or remove an element. Each operation has an associated cost, and the goal is to find the sequence of edits with the lowest total cost.

The problem can be stated naturally as a recursion, a sequence A is optimally edited into a sequence B by either:

- inserting the first character of B, and performing an optimal alignment of A and the tail of B

- deleting the first character of A, and performing the optimal alignment of the tail of A and B

- replacing the first character of A with the first character of B, and performing optimal alignments of the tails of A and B.

The partial alignments can be tabulated in a matrix, where cell (i,j) contains the cost of the optimal alignment of A[1..i] to B[1..j]. The cost in cell (i,j) can be calculated by adding the cost of the relevant operations to the cost of its neighboring cells, and selecting the optimum.

Different variants exist, see Smith-Waterman and Needleman-Wunsch.

[edit] Algorithms that use dynamic programming

- Many string algorithms including longest common subsequence, longest increasing subsequence, longest common substring.

- Many algorithmic problems on graphs can be solved efficiently for graphs of bounded treewidth or bounded clique-width by using dynamic programming on a tree decomposition of the graph.

- The Cocke-Younger-Kasami (CYK) algorithm which determines whether and how a given string can be generated by a given context-free grammar

- The use of transposition tables and refutation tables in computer chess

- The Viterbi algorithm (used for hidden Markov models)

- The Earley algorithm (a type of chart parser)

- The Needleman-Wunsch and other algorithms used in bioinformatics, including sequence alignment, structural alignment, RNA structure prediction.

- Levenshtein distance (edit distance)

- Floyd's All-Pairs shortest path algorithm

- Optimizing the order for chain matrix multiplication

- Pseudopolynomial time algorithms for the Subset Sum and Knapsack and Partition problem Problems

- The dynamic time warping algorithm for computing the global distance between two time series

- The Selinger (a.k.a System R) algorithm for relational database query optimization

- De Boor algorithm for evaluating B-spline curves

- Duckworth-Lewis method for resolving the problem when games of cricket are interrupted

- The Value Iteration method for solving Markov decision processes

- Some graphic image edge following selection methods such as the "magnet" selection tool in Photoshop

- Interval scheduling

- Word wrap

- Travelling salesman problem

- Segmented least squares method

- Beat tracking in Music Information Retrieval.

- Adaptive Critic training strategy for artificial neural networks

- Stereo algorithms for solving the Correspondence problem used in stereo vision.

- Selling an asset for several time periods.

- Optimal production/inventory management.

- Seam carving (content aware image resizing)

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- Adda, Jerome, and Cooper, Russell, 2003. Dynamic Economics. MIT Press. An accessible introduction to dynamic programming in economics. The link contains sample programs.

- Richard Bellman, 1957, Dynamic Programming, Princeton University Press. Dover paperback edition (2003), ISBN 0486428095.

- Bertsekas, D. P., 2000. Dynamic Programming and Optimal Control, Vols. 1 & 2, 2nd ed. Athena Scientific. ISBN 1-886529-09-4.

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein, 2001. Introduction to Algorithms, 2nd ed. MIT Press & McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Especially pp. 323–69.

- Giegerich, R., Meyer, C., and Steffen, P., 2004, "A Discipline of Dynamic Programming over Sequence Data," Science of Computer Programming 51: 215-263.

- Nancy Stokey, and Robert E. Lucas, with Edward Prescott, 1989. Recursive Methods in Economic Dynamics. Harvard Univ. Press.

- S. P. Meyn, 2007. Control Techniques for Complex Networks, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[edit] External links

- An Introduction to Dynamic Programming

- Dyna, a declarative programming language for dynamic programming algorithms

- Wagner, David B., 1995, "Dynamic Programming." An introductory article on dynamic programming in Mathematica.

- Ohio State University: CIS 680: class notes on dynamic programming, by Eitan M. Gurari

- A Tutorial on Dynamic programming

- MIT course on algorithms - Includes a video lecture on DP along with lecture notes

- More DP Notes

- King, Ian, 2002 (1987), "A Simple Introduction to Dynamic Programming in Macroeconomic Models." An introduction to dynamic programming as an important tool in economic theory.

- Dynamic Programming: from novice to advanced A TopCoder.com article by Dumitru on Dynamic Programming

- Algebraic Dynamic Programming - a formalized framework for dynamic programming, including an entry-level course to DP, University of Bielefeld

- Dreyfus, Stuart, "Richard Bellman on the birth of Dynamic Programming."

- Dynamic programming tutorial

- A Gentle Introduction to Dynamic Programming and the Viterbi Algorithm