Beau Brummell

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

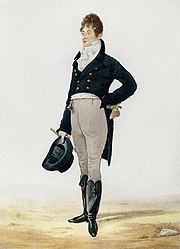

Beau Brummell, né George Bryan Brummell (7 June 1778, London, England – 30 March 1840, Caen, France), was the arbiter of men's fashion in Regency England and a friend of the Prince Regent, the future King George IV. He established the mode of men wearing understated, but fitted, beautifully cut clothes including dark suits and full length trousers, adorned with an elaborately-knotted cravat.[1]

Beau Brummell is credited with introducing and establishing as fashion the modern man's suit, worn with a tie.[2] He claimed to take five hours to dress, and recommended that boots be polished with champagne.[3] His style of dress was known as dandyism.[4]

Contents |

[edit] Biography

George was the son of the private secretary of Lord North. He was fair complexioned, and had "a high nose, which was broken down by a kick from a horse soon after he went into the Tenth Dragoons...."[5] His father died in 1794, leaving him an inheritance of over 20,000 pounds. He was an undergraduate at Oriel College, and later embarked upon a military career, joining the Tenth Light Dragoons. It was during this time he came to the attention of Prince George, the Prince of Wales. Through the influence of the Prince, Brummell had been promoted to captain by 1796. When his regiment was sent from London to Manchester, however, he resigned his commission. [6]

Beau Brummell took a house on Chesterfield Street in Mayfair, and, for a time, avoided extravagance and gaming. For example, he kept horses but no carriages. He was included in Prince George's circle. Here, he made an impression with his elegant understated manner of dress and clever remarks. His fastidious attention to cleaning his teeth, shaving, and bathing daily became popular.

He was influenced by his wealthy friends as well. He began spending and gambling as though his fortune were as great as theirs. This was not a problem while he could still float credit. Brummell, Lord Alvanley, Henry Mildmay and Henry Pierrepoint were considered the prime movers of Watier's, dubbed "the Dandy Club" by Byron. They were also the four hosts of the masquerade ball in July 1813 at which the Prince Regent greeted Alvanley and Pierrepoint, but then "cut" Brummell and Mildmay by snubbing them, staring them in the face but not speaking to them[7]. This provoked Brummell's infamous remark, "Alvanley, who's your fat friend?". This finalized the long-developed rift between them, dated by Campbell to 1811, the year the Prince became Regent and began abandoning all his old Whig friends. Normally, the loss of royal favour to a favourite was doom, but Brummell ran as much on the approval and friendship of other rulers of the several fashion circles. He became the anomaly of a favourite flourishing without a patron, still in charge of fashion and courted by large segments of society. [8]

However, his spiralling debt spun out of control, and he tried to recover by devices that only dug the hole deeper. [9] In 1816, he fled to France to escape debtor's prison from the demands for payment in full of thousands of pounds sterling owed. Usually, Brummell's gambling debts, as "debts of honour", were always paid immediately. The one exception to this was the final wager recorded for him in White's betting book. Recorded March, 1815, the debt was marked "not paid, 20th January, 1816".[10]

He lived the remainder of his life in France, acquiring an appointment to the consulate at Caen due to the influence of Lord Alvanley and the Marquess of Worcester, only in the reign of William IV. This provided him with a small annuity. He died penniless and insane from strokes and syphilis in Caen in 1840.

A statue of Brummell by Irena Sedlecka was erected on London's Jermyn Street in 2002.[11]

[edit] In popular culture

Brummell appears as a character in Arthur Conan Doyle's 1896 historical novel Rodney Stone. In the novel, the title character's uncle, Charles Tregellis, is the center of the London fashion world, until Brummell ultimately supplants him. Tregellis' subsequent death from mortification serves as a deus ex machina in that it resolves Rodney Stone's family poverty, as his rich uncle bequeaths a sum to his sister.

Brummell's life was later dramatised in

- an 1890 stage play by American playwright Clyde Fitch;

- a 1924 movie with John Barrymore and Mary Astor;

- a 1931 operetta by Reynaldo Hahn, also broadcast by Radio-Lille (1963);

- a 1937 production on Lux Radio Theater with Robert Montgomery as Brummell and Gene Lockhart as the Prince; (during the introduction of this episode, Cecil B. DeMille calls for prayers for finding Amelia Earhart);

- a 1954 movie remake, Beau Brummell, with Stewart Granger playing the title role.[12] The character of Lady Patricia Belham was invented for this film in order to present Brummell as unambiguously heterosexual, in accordance with the PCA's strictures.

- A 2006 BBC television drama, Beau Brummell: This Charming Man starring James Purefoy as Brummell, and first broadcast on BBC Four in June 2006.[13]

Georgette Heyer, author of a number of Regency romance novels, included Brummell as a character in her 1935 novel Regency Buck.

Brummell is a minor character in T. Coraghessan Boyle's 1993 novel, "Water Music".

Watchmaker LeCoultre made a watch named after him during the 1940s and 1950s. It is an extremely simple watch with no numbers and a small modern face.

The Puig Beauty & Fashion Group has a eau de cologne named after Brummel.

Brummell's name was adopted by the faux-British Invasion band The Beau Brummels who had top 40 hit records in 1965.

Brummell's name was also used by an English group, Beau Brummell Esquire and His Noble Men, who released at least one single, "I Know, Know, Know" b/w "Shopping Around" (Columbia DB 7447), in 1965. The "A side" song was written by Beau Brummell Esquire; the "B side" song is credited to Tepper-Bennett-Schroeder, a trio of professional song writers who had previously written hits for Cliff Richard.

Brummell is the detective-hero of a series of period mysteries by Rosemary Stevens, including Death on a Silver Tray (2000), The Tainted Snuff Box (2001), The Bloodied Cravat (2002), and Murder in the Pleasure Gardens (2003).

The Beau Brummel store in New York City's trendy SoHo neighborhood offers a line of traditional menswear, including the eponymous Beau Brummel suit, which Regis Philbin has worn on television in Live with Regis and Kelly and Who Wants to be a Millionaire.

Billy Joel references Brummell in his hit 1980 song "It's Still Rock and Roll to Me." He sings about wearing pink sidewinders (which are apparently a type of dance shoe) and bright orange pants.

In the 1982 film Annie (film), the song "You're Never Fully Dressed Without a Smile" features the lyrics, "Your clothes may be Beau Brummelly- They stand out a mile..." referencing Brummell's eclectic manner of dress.

Marc Bolan, as a young mod, told Town Magazine in 1962 that, after reading his biography, he saw Brummel as a great influence stating "He was just like us really, you know, came up from nothing".

[edit] References and footnotes

- ^ "A Poet of Cloth", a Spring 2006 article on Brummell's cravats from Cabinet magazine

- ^ Kelly, Ian (September 17, 2005), "The man who invented the suit", The Times Online, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,23113-1782054_1,00.html, retrieved on 2008-02-01

- ^ Beau Brummell and the Birth of Regency Fashion, from the Jane Austen Centre's online magazine

- ^ Barbey d'Aurevilly, Jules. Of Dandyism and of George Brummell. Translated by Douglas Ainslie. New York: PAJ Publications, 1988.

- ^ Jesse, William (1844), The Life of George Brummell, Esq., Commonly Called Beau Brummell, Great Britain: Saunders and Otley, p. 383

- ^ Jesse

- ^ The Wits and Beaux of Society, Volume 2, Grace and Phillip Wharton, 1861

- ^ Kelly, Campbell, Jerrold

- ^ Campbell

- ^ The Regency Underworld, Donald A Lowe

- ^ Memorial to Brummell from londonremembers.com

- ^ Beau Brummell at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ James Purefoy as Brummell in a BBC television drama

[edit] Further reading

- Barbey d'Aurevilly, Jules. Of Dandyism and Of George Brummell, 1845

- Campbell, Kathleen. Beau Brummell. London: Hammond, 1948

- Jesse, Captain William. The Life of Beau Brummell. London: The Navarre Society Limited, 1927.

- Kelly, Ian. Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style. Hodder & Stoughton, 2005

- Lewis, Melville. Beau Brummell: His Life and Letters. New York: Doran, 1925

- Moers, Ellen. The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm. London: Secker and Warburg, 1960.

- Nicolay, Claire. Origins and Reception of Regency Dandyism: Brummell to Baudelaire. Ph. D. diss., Loyola U of Chicago, 1998.

- Wharton, Grace and Philip. Wits and Beaux of Society. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1861.