The Ambassadors (Holbein)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

| The Ambassadors |

| Hans Holbein the Younger, 1533 |

| Oil on oak |

| 207 cm × 209.5 cm (81 in × 82 in) |

| National Gallery, London |

The Ambassadors (1533) is a painting by Hans Holbein the Younger in the National Gallery, London. As well as being a double portrait, the painting contains a still life of several meticulously rendered objects, the meaning of which is the cause of much debate. It is also a much-cited example of anamorphosis in painting.

Contents |

[edit] Description

Although a German-born artist who spent much time in England, Holbein displayed the influence of Early Netherlandish painters in this work. This influence can be noted most outwardly in the use of oil paint, the use of which for panel paintings had been developed a century before in Early Netherlandish painting. What is most "Flemish" of Holbein's use of oils is his use of the medium to render meticulous details that are mainly symbolic: as Van Eyck and the Master of Flemalle used extensive imagery to link their subjects to divinity, Holbein used symbols to link his figures to the age of exploration.

Among the clues to the figures' explorative associations are two globes (one terrestrial and one celestial), a quadrant, a torquetum, a polyhedral sundial and various textiles: the floor mosaic, based on a design from Westminster Abbey (the Cosmati pavement, before the High Altar), and the carpet on the upper shelf, which is most notably oriental. The choice for the inclusion of the two figures can furthermore be seen as symbolic. The figure on the left is in secular attire while the figure on the right is dressed in clerical clothes. They are flanking the table, which displays open books, symbols of religious knowledge and even a symbolic link to the Virgin, is therefore believed by some critics to be symbolic of a unification of capitalism and the Church.[citation needed]

In contrast, other scholars have suggested the painting contains overtones of religious strife. The conflicts between secular and religious authorities are here represented by Jean de Dinteville, a landowner, and Georges de Selve, a bishop. The commonly accepted symbol of discord, a lute with a broken string, is included next to a hymnbook in Martin Luther's translation, suggesting strife between scholars and the clergy.[1]

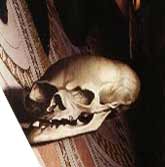

The most notable and famous of Holbein's symbols in the work, however, is the skewed skull which is placed in the bottom centre of the composition. The skull, rendered in anamorphic perspective, another invention of the Early Renaissance, is meant to be a visual puzzle as the viewer must approach the painting nearly from the side to see the form morph into an accurate rendering of a human skull. While the skull is evidently intended as a vanitas or memento mori, it is unclear why Holbein gave it such prominence in this painting. One possibility is that this painting represents three levels: the heavens (as portrayed by the astrolabe and other objects on the upper shelf), the living world (as evidenced by books and a musical instrument on the lower shelf), and death (signified by the skull). It has also been hypothesized that the painting is meant to hang in a stairwell, so that a person walking up the stairs from the painting's left would be startled by the appearance of the skull. A further possibility is that Holbein simply wished to show off his ability with the technique in order to secure future commissions.[2] Artists often incorporated skulls as a reminder of mortality, or at the very least, death. Holbein may have intended the skulls (one as a gray slash and the other as a medallion on Jean de Dinteville's hat) and the crucifixion in the corner to encourage contemplation of one's impending death and the resurection.[3]

[edit] Interpretation

Until the publication of Mary F. S. Hervey's Holbein's Ambassadors: The Picture and the Men in 1900, the identity of the two figures in the picture had been for a long time a matter of intense debate. In 1890, Sidney Colvin was the first to propose the figure on the left as Jean de Dinteville, Seigneur of Polisy (1504–1555), French ambassador to the court of Henry VIII for most of 1533. Shortly afterwards, the cleaning of the picture revealed that his seat of Polisy is one of only four places marked on the globe.[4] Hervey identified the man on the right as Georges de Selve (1508/09–1541), Bishop of Lavaur, after tracing the painting's history back to a seventeenth-century manuscript. According to art historian John Rowlands, de Selve is not wearing episcopal robes because he was not consecrated until 1534.[5] De Selve is known from two of de Dinteville's letters to his brother François de Dinteville, Bishop of Auxerre, to have visited London in the spring of 1533. On 23 May, Jean de Dinteville wrote: "Monsieur de Lavaur did me the honour of coming to see me, which was no small pleasure to me. There is no need for the grand maître to hear anything of it". The grand maître in question was Anne de Montmorency, the Marshal of France, a reference that has led some analysts to conclude that de Selve's mission was a secret one; but there is no other evidence to corroborate the theory.[6] On June 4, the ambassador wrote to his brother again, saying: "Monsieur de Lavaur came to see me, but has gone away again".[7]

Hervey's identification of the sitters has remained the standard one, affirmed in extended studies of the painting by Foister, Roy, and Wyld (1997), Zwingenberger (1999), and North (2004), who concludes that "the general coherence of the evidence assembled by Hervey is very satisfying"; however, North also notes that, despite Hervey's research, "[R]ival speculation did not stop at once and is still not entirely dead".[8] Recent opposition to the identification of de Selve has been based on an inventory of 1589, discovered by Riccardo Famiglietti, which names the man on the right as de Dinteville's brother François.[9] However, scholars have argued that this identification of 1589 was incorrect. John North, for example, remarks that "[T]his was a natural enough supposition to be made by a person with limited local knowledge, since the two brothers lived on the family estates together at the end of their lives, but it is almost certainly mistaken".[10] He points to a letter François de Dinteville wrote to Jean on 28 March 1533, in which he talks of an imminent meeting with the pope and makes no mention of visiting London. Unlike the man on the right of the picture, François was older than Jean de Dinteville. The inscription on the man on the right's book is "AETAT/IS SV Æ 25" (his age is 25); that on de Dinteville's dagger is "AET. SV Æ/ 29" (he is 29).[11]

[edit] See also

[edit] Footnotes

[edit] References

- Foister, Susan; Ashok Roy and Martin Wyld (1997). Making and Meaning: Holbein's Ambassadors. London: National Gallery Publications. ISBN 1857091736.

- Hervey, Mary (1900). Holbein's Ambassadors: The Picture and the Men. London: George Bell and Sons.

- Hudson, Giles (April, 2003). "The Vanity of the Sciences". Annals of Science 60 (2): pp. 201–205. doi:.

- Mamiya, Christin J. (2005). Gardner's Art Through the Ages 12th ed. California: Wadsworth/ Thomson Learning, Inc. ISBN 0155050907.

- North, John (2004). The Ambassadors' Secret: Holbein and the World of the Renaissance. London: Phoenix. ISBN 184212661X.

- Rowlands, John (1985). Holbein: The Paintings of Hans Holbein the Younger. Boston: David R. Godine. ISBN 0879235780.

- Zwingenberger, Jeanette (1999). The Shadow of Death in the Work of Hans Holbein the Younger. London: Parkstone Press. ISBN 1859954928.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: The Ambassadors (Holbein) |