Jim Henson

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- For other uses of "Henson", see: Henson.

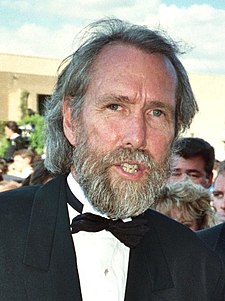

| Jim Henson | |

at the 1989 Emmy Awards.

|

|

| Born | James Maury Henson September 24, 1936 Greenville, Mississippi, USA |

|---|---|

| Died | May 16, 1990 (aged 53) New York, New York, USA |

| Occupation | Puppeteer, film director and television producer |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Henson (m. 1959–1990) |

| Children | Lisa Henson Cheryl Henson Brian Henson John Henson Heather Henson |

James Maury "Jim" Henson (September 24, 1936, Greenville, Mississippi – May 16, 1990, New York, New York), was one of the most widely known puppeteers in American history.[1] He was the creator of The Muppets, and the leading force behind their long run in the television series Sesame Street and The Muppet Show and films such as The Muppet Movie (1979) and creator of advanced puppets for projects like Fraggle Rock, The Dark Crystal, Labyrinth and Return Of The Jedi. He was also an Oscar-nominated film director, Emmy Award-winning television producer, and the founder of The Jim Henson Company, the Jim Henson Foundation, and Jim Henson's Creature Shop.

Henson's sudden death on May 16, 1990, of Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome (STSS, not to be confused with TSS), resulted in an outpouring of public and professional affection. There have since been numerous tributes and dedications in his memory. Henson’s companies, which are now run by his children, continue to produce films and television shows.

On September 26, 1992, Henson was posthumously awarded the Courage of Conscience Award for being a "Humanitarian, muppeteer, producer and director of films for children that encourage tolerance, interracial values, equality and fair play."[2]

Contents |

[edit] Early life

Jim Henson was the younger of two boys. His parents were Paul Henson, agronomist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Elizabeth Marcella Henson.[3] After spending his early childhood in Leland, Mississippi, he moved with his family to Hyattsville, Maryland, near Washington, DC, in the late 1940s. Henson was raised as a Christian Scientist;[4] he later remembered the arrival of the family's first television as "the biggest event of his adolescence,"[5] being heavily influenced by radio ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and the early television puppets of Burr Tillstrom (on Kukla, Fran and Ollie) and Bil and Cora Baird.[5]

In 1954, while attending Northwestern High School, he began working for WTOP-TV creating puppets for a Saturday morning children's show. After graduating from high school, Henson enrolled at University of Maryland, College Park as a studio arts major, thinking he might become a commercial artist.[6] A puppetry class offered in the applied arts department introduced him to the craft and textiles courses in the College of Home Economics, and he graduated with a B.S. in home economics in 1960. As a freshman, he was asked to create Sam and Friends, a five-minute puppet show for WRC-TV. The characters on Sam and Friends were already recognizable Muppets, and the show included a primitive version of what would become Henson's most famous character, Kermit the Frog.[7]

In the show, he began experimenting with techniques that would change the way puppetry was used on television, including using the frame defined by the camera shot to allow the puppeteer to work from off-camera. Henson believed that television puppets needed to have "life and sensitivity,"[8] and so, at a time when many puppets were made out of carved wood, Henson began making characters from flexible, fabric-covered foam rubber, allowing them to express a wider array of emotions.[3] In contrast to a marionette, whose arms are manipulated by strings, Henson used rods to move his muppets' arms, allowing for greater control of expression. Additionally, Henson wanted the muppet characters to "speak" more creatively than previous puppets, which had seemed to have random mouth movements; he used, and directed his muppeteers to use, precision mouth movements to match the dialogue.

When Henson began work on Sam and Friends, he asked fellow University of Maryland freshman, Jane Nebel, to assist him. The show was a financial success, but after graduating from college, Jim began to have doubts about going into a career as a puppeteer. He wandered off to Europe for several months, where he was inspired by European puppeteers who looked on their work as a form of art.[9] Henson returned to the United States and he and Jane began dating. They were married in 1959 and had five children: Lisa (b. 1960), Cheryl (b. 1962), Brian (b. 1963), John (b. 1965) and Heather (b. 1970).

[edit] Struggles and projects in the 1960s

Despite the success of Sam and Friends, which ran for six years, Henson spent much of the next two decades working in commercials, talk shows, and children's projects before being able to realize his dream of the Muppets as "entertainment for everybody".[5] The popularity of his work on Sam and Friends in the late fifties led to a series of guest appearances on network talk and variety shows. Henson himself appeared as a guest on many shows, including The Ed Sullivan Show. This greatly increased exposure led to hundreds of commercial appearances by Henson characters through the sixties.

Among the most popular of Henson's commercials was a series for the local Wilkins Coffee company in Washington, D.C.,[10] in which his Muppets were able to get away with a greater level of slapstick violence than might have been acceptable with human actors. In the first Wilkins ad, a Muppet named Wilkins is poised behind a cannon seen in profile. Another Muppet named Wontkins is in front of its barrel. Wilkins asks, "What do you think of Wilkins Coffee?" to which Wontkins responds gruffly, "Never tasted it!" Wilkins fires the cannon and blows Wontkins away, then turns the cannon directly toward the viewer and ends the ad with, "Now, what do you think of Wilkins?" Henson later explained, "Till then, [advertising] agencies believed that the hard sell was the only way to get their message over on television. We took a very different approach. We tried to sell things by making people laugh."[11] The first seven-second commercial for Wilkins was an immediate hit and was syndicated and reshot by Henson for local coffee companies across the United States;[10] he ultimately produced more than 300 coffee ads.[11] The same setup was used to pitch Kraml Milk in the Chicago, Il., area.

In 1963, Henson and his wife moved to New York City, where the newly formed Muppets, Inc. would reside for some time. When Jane quit muppeteering to raise their children, Henson hired writer Jerry Juhl in 1961 and puppeteer Frank Oz in 1963 to replace her;[12] Henson later credited both with developing much of the humor and character of his Muppets.[13] Henson and Oz, particularly, developed a close friendship and a performing partnership that lasted 27 years; their teamwork is particularly evident in their portrayals of the characters of Bert and Ernie and Kermit and Fozzie Bear.[14]

Henson's sixties talk show appearances culminated when he devised Rowlf, a piano-playing anthropomorphic dog. Rowlf became the first Muppet to make regular appearances on a network show, The Jimmy Dean Show. From 1964 to 1968, Henson began exploring film-making and produced a series of experimental films. His nine-minute Time Piece was nominated by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for an Oscar for Short Film in 1966. Jim Henson also produced another experimental film, The NBC-TV movie The Cube, in 1969.

[edit] Sesame Street

In 1969, Joan Ganz Cooney and the team at the Children's Television Workshop asked Henson to work on Sesame Street, a visionary children's program for public television. Part of the show was set aside for a series of funny, colorful puppet characters living on the titular street. These included Oscar the Grouch, Bert and Ernie, Cookie Monster, and Big Bird. Henson performed the characters of Ernie, game-show host Guy Smiley, and Kermit, who appeared as a roving television news reporter. It was around this time that a frill was added around Kermit's neck to make him more frog-like. The collar was also used to cover the joint where the neck met the body of the Muppet.

At first, Henson's Muppets appeared separately from the realistic segments on the street, but after a poor test screening in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the show was revamped to integrate the two and place much greater emphasis on Henson's work. Though Henson would often downplay his role in Sesame Street's success, Cooney frequently praised his work and, in 1990, the Public Broadcasting Service called him "the spark that ignited our fledgling broadcast service."[5] The success of Sesame Street also allowed Henson to stop producing commercials. He later remembered that "it was a pleasure to get out of that world."[10]

Concurrently with the first years of Sesame Street, Henson directed Tales From Muppetland, a short series of TV movie specials aimed at a young audience and hosted by Kermit the Frog. The series included Hey, Cinderella!, The Frog Prince, and The Muppet Musicians of Bremen. These specials were comedic tellings of classic fairy-tale stories.

[edit] Finding a wider audience

Henson, Oz, and his team targeted an adult audience with a series of sketches on the first season of the groundbreaking comedy series Saturday Night Live (SNL). Eleven sketches, set mostly in the Land of Gorch, aired between October 1975 and January 1976, with four additional appearances in March, April, May, and September. Henson recalled that "I saw what [creator Lorne Michaels] was going for and I really liked it and wanted to be a part of it, but somehow what we were trying to do and what his writers could write for it never jelled."[10] The SNL writers never got comfortable writing for the characters, and frequently disparaged Henson's creations; one, Michael O'Donoghue, memorably quipped, "I won't write for felt."[15]

Around the time of his characters' final appearances on SNL, Henson began developing two projects featuring the Muppets: a Broadway show and a weekly television series.[10] The series was initially rejected by the American networks, who believed that Muppets would only appeal to children; in 1976, Henson was finally able to convince British impresario Lew Grade to finance the show, which would be shot in the United Kingdom and syndicated across the globe.[9] That same year, he abandoned work on the Broadway show and moved his creative team to England, where The Muppet Show began filming. The show featured Kermit as host, and a variety of other memorable characters including Miss Piggy, Gonzo the Great, and Fozzie Bear. Henson's role in Muppet productions was often compared by his co-workers to Kermit's role on The Muppet Show: a shy, gentle boss with "a whim of steel"[14] who "[ran] things as firmly as it is possible to run an explosion in a mattress factory."[16] Carroll Spinney, the puppeteer of Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch, remembered that Henson "would never say he didn't like something. He would just go 'Hmm.' That was famous. And if he liked it, he would say, 'Lovely!' "[4] Henson himself recognized Kermit as an alter-ego, though he thought that Kermit was bolder than he was; he once said of Kermit, "He can say things I hold back."[17]

[edit] Transition to the big screen

Three years after the start of The Muppet Show, the Muppets appeared in their first theatrical feature film, 1979's The Muppet Movie. The film was both a critical and financial success;[18] it made US$65.2 million domestically and (at the time) was the 61st highest-grossing film ever made.[19] A song from the film, "The Rainbow Connection," sung by Henson as Kermit, hit #25 on the Billboard Hot 100 and was nominated for an Academy Award. In 1981, a Henson-directed sequel, The Great Muppet Caper, followed, and Henson decided to end the still-popular Muppet Show to concentrate on making films.[3] From time to time, the Muppet characters continued to appear in made-for-TV-movies and television specials.

In addition to his own puppetry projects, Henson also aided others in their work. In 1979, he was asked by the producers of the Star Wars film The Empire Strikes Back to aid make-up artist Stuart Freeborn in the creation and articulation of enigmatic Jedi Master Yoda. Henson suggested to Star Wars creator George Lucas that he use Frank Oz as the puppeteer and voice of Yoda. Oz voiced Yoda in Empire and each of the four subsequent Star Wars films, and the naturalistic, lifelike Yoda became one of the most popular characters in the Star Wars films.[20]

In 1982, Henson founded the Jim Henson Foundation to promote and develop the art of puppetry in the United States. Around that time, he also began creating darker and more realistic fantasy films that did not feature the Muppets and displayed "a growing, brooding interest in mortality."[14] With 1982's The Dark Crystal, which he co-directed with Frank Oz and also co-wrote, Henson said he was "trying to go toward a sense of realism—toward a reality of creatures that are actually alive [where] it's not so much a symbol of the thing, but you're trying to [present] the thing itself."[10] To provide a visual style distinct from the Muppets, the puppets in The Dark Crystal were based on conceptual artwork by Brian Froud.

Crystal was a financial and critical success, and, a year later, the Muppet-starring The Muppets Take Manhattan (directed by Frank Oz) did fair box-office business, grossing $25.5 million domestically and ranking as one of the top 40 films of 1984.[21] However, 1986's Labyrinth, a Crystal-like fantasy that Henson directed by himself, was considered (in part due to its cost) a commercial disappointment. Despite some positive reviews (The New York Times called it "a fabulous film"),[22] the commercial failure of Labyrinth demoralized Henson to the point that son Brian Henson remembered the time of its release as being "the closest I've seen him to turning in on himself and getting quite depressed."[14] (The film later became a cult classic.)[23] Henson and his wife also separated the same year, although they remained close for the rest of his life.[4] Jane later said that Jim was so involved with his work that he had very little time to spend with her or their children.[4] All five of his children began working with Muppets at an early age, partly because, Cheryl Henson remembered, "One of the best ways of being around him was to work with him."[8]

[edit] Later work

Though he was still engaged in creating children's programming, such as the successful eighties shows Fraggle Rock and the animated Muppet Babies, Henson continued to explore darker, mature themes with the folk tale and mythology oriented show The Storyteller (1988). The Storyteller won an Emmy for Outstanding Children's Program but was cancelled after nine episodes. The next year, Henson returned to television with The Jim Henson Hour, which mixed lighthearted Muppet fare with riskier material. The show was critically well-received and won Henson another Emmy for Outstanding Directing in a Variety or Music Program, but was cancelled after 13 episodes due to low ratings. Henson blamed its failure on NBC's constant rescheduling.[24]

In late 1989, Henson entered into negotiations to sell his company to The Walt Disney Company for almost $150 million, hoping that, with Disney handling business matters he would "be able to spend a lot more of my time on the creative side of things."[24] By 1990, he had completed production on a television special, The Muppets at Walt Disney World, and a Disney World (Later Disney's California Adventure as well) attraction, Jim Henson's Muppet*Vision 3D, and was developing film ideas and a television series titled Muppet High.[4]

[edit] Natural History Project and Dinosaurs

In the late 1980s, Henson worked with illustrator/designer William Stout on a feature film starring animatronic dinosaurs with the working title of The Natural History Project. In 1991, news stories written around the premiere of the Jim Henson Company-produced Dinosaurs sitcom highlighted the show's connection to Henson, who had died the year before. "Jim Henson dreamed up the show's basic concept about three years ago," said a New York Times article in April 1991. "'He wanted it to be a sitcom with a pretty standard structure, with the biggest differences being that it's a family of dinosaurs and their society has this strange toxic life style,' said [his son] Brian Henson. But until The Simpsons took off, said Alex Rockwell, a vice president of the Henson organization, 'people thought it was a crazy idea.'"[25] A New Yorker article said that Henson continued to work on a dinosaur project (presumably the Dinosaurs concept) until the "last months of his life."[26]

[edit] Death

While busy with these later projects, Henson began to experience flu-like symptoms.[4]

On May 4, 1990, Henson made an appearance on The Arsenio Hall Show. At the time, he mentioned to his publicist that he was tired and had a sore throat, but felt that it would go away.

On May 12, 1990, Henson traveled to Ahoskie, North Carolina, with his daughter Cheryl to visit his father and stepmother. The next day, feeling tired and sick, he consulted a physician in North Carolina, who could find no evidence of pneumonia by physical examination and prescribed no treatment except aspirin.[27] Henson returned to New York on an earlier flight and canceled a Muppet recording session scheduled for May 14.

Henson's wife Jane, from whom he was separated, came to visit and sat with him talking throughout the evening. By 2 a.m. on May 15, 1990 he was having trouble breathing and began coughing up blood. He suggested to Jane that he might be dying, but did not want to bother going to the hospital. She later told People Magazine that it was likely due to his desire not to be a bother to people.[4]

At 4 a.m., he finally agreed to go to New York Hospital, at which point his body was rapidly shutting down. By the time he was admitted at 4:58 a.m., he could no longer breathe on his own and had abscesses in his lungs. He was placed on a mechanical ventilator to help him breathe, but his condition deteriorated rapidly into septic shock despite aggressive treatment with multiple antibiotics. On Wednesday May 16, 1990, 21 hours and 23 minutes after he was admitted, at 1:21 a.m., Henson died from organ failure at the age of 53 at New York Hospital.

The cause of death was first reported as streptococcus pneumonia, a bacterial infection.[5] Bacterial pneumonia is usually caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, an alpha-hemolytic species of Streptococcus. Henson, however, died of organ failure due to infection by Streptococcus pyogenes, a severe Group A streptococcal infection, that engulfed his body.[28] S. pyogenes is the bacterial species that causes scarlet fever, rheumatic fever and, in Henson's case, Toxic Shock Syndrome.

Two separate memorial services were held for Henson, one in New York City at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine and one in London, England, at St. Paul's Cathedral. As per Henson's wishes, no one in attendance wore black, and a Dixieland jazz band finished the service by performing "When The Saints Go Marching In." Harry Belafonte sang "Turn the World Around," a song he had debuted on The Muppet Show, as each member of the audience waved, with a puppeteer's rod, an individual, brightly-colored foam butterfly.[29] Later, Big Bird (performed by Carroll Spinney) walked out onto the stage and sang Kermit the Frog's signature song, "Bein' Green."[30]

In the final minutes of the two-and-a-half hour service, six of the core Muppet performers sang, in their characters' voices, a medley of Jim Henson's favorite songs, culminating in a performance of "Just One Person" that began with Richard Hunt singing alone, as Scooter. "As each verse progressed," Henson employee Chris Barry recalled, "each Muppeteer joined in with their own Muppets until the stage was filled with all the Muppet performers and their beloved characters."[30] The funeral was later described by LIFE as "an epic and almost unbearably moving event." The image of a growing number of performers singing "Just One Person" was recreated for the 1990 television special The Muppets Celebrate Jim Henson and inspired screenwriter Richard Curtis, who attended the London service, to write the growing-orchestra wedding scene of his 2003 film Love Actually.[31]

Jim was cremated at Ferncliff Cemetery. His ashes were scattered in Santa Fe, New Mexico, at his ranch.[32]

[edit] Business legacy

The Jim Henson Company and the Jim Henson Foundation continued after his death, producing new series and specials. Jim Henson's Creature Shop, founded by Henson, also continues to build creatures for a large number of other films and series (most recently the science fiction production Farscape, the film adaptation of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, and the movie MirrorMask) and is considered one of the most advanced and well respected creators of film creatures. His son Brian and daughter Lisa are currently the co-chairs and co-CEOs of the company; his daughter Cheryl is the president of the foundation. Steve Whitmire, a veteran member of the Muppet puppeteering crew, has assumed the roles of Kermit the Frog and Ernie, the most famous characters formerly played by Jim Henson.[33]

On February 17, 2004, it was announced that the Muppets (excluding the Sesame Street characters, which are separately owned by Sesame Workshop) and the Bear in the Big Blue House properties had been sold by Henson's heirs to The Walt Disney Company. The Jim Henson Company retains the Creature Shop, as well as the rest of its film and television library including Fraggle Rock, Farscape, The Dark Crystal, and Labyrinth.[34]

In February 2008, the Empire Film Group announced that it was planning to produce and distribute Henson, a film chronicling the life and achievements of Jim Henson. The film's screenplay was written by Robert D. Slane, and Empire plans to attract "a major director, such as Penny Marshall" and "notable star cast in key roles."[35]

[edit] Tributes

- The Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta, Georgia, has acquired more than 700 puppets created by Henson and his studio, including some of the earliest Muppets. Many of these are displayed in the museum exhibit Jim Henson: Puppeteer. In September 2008, the Center for Puppetry Arts opened Jim Henson: Wonders From His Workshop, highlighting creations from Fraggle Rock, Labyrinth, and other later works.

- Henson is honored both as himself and as Kermit the Frog on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. The only other person to receive this honor is Mel Blanc, the voice actor of Bugs Bunny.

- The classes of 1994, 1998, and 1999 at the University of Maryland, College Park, Henson's alma mater, commissioned a life-size statue of Henson and Kermit the Frog, which was dedicated on September 24, 2003, Henson's 67th birthday. The statue cost $217,000, and is displayed outside Maryland's student union.[36] In 2006, Maryland introduced 50 statues of their school mascot, Testudo the Terrapin, with various designs chosen by different sponsoring groups. Among them was Kertle, a statue by Washington DC artist Elizabeth Baldwin designed to look like Kermit the Frog.

- The theater at his alma mater, Northwestern High School, in Hyattsville, MD, is named in his honor.

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze and The Muppet Christmas Carol are both dedicated to him.

- The television special The Muppets Celebrate Jim Henson allowed the Muppets themselves to pay tribute to Henson. The special featured interviews with Steven Spielberg and others.

- A museum was built in memory of Henson in Leland, Mississippi. Official certificates from the Mississippi Legislature honoring Jim Henson and Muppets paraphernalia are on display.

- Tom Smith's Henson tribute song, "A Boy and His Frog," won the Pegasus Award for Best Filk Song in 1991.

- Stephen Lynch produced a song titled "Jim Henson's Dead," in which he pays homage to many of the characters from The Muppet Show and Sesame Street.

- J. G. Thirlwell (under the alias Foetus In Excelsis Corruptus) performed a reworked version of Elton John's "Rocket Man" titled "Puppet Dude," with the lyrics altered to refer to Jim Henson. This can be found on the Male live album.

- Apple Computer's "Think Different" advertising campaign featured Henson.

- Oury Atlan, Thibaut Berland, and Damien Ferri wrote, directed, and animated a 3D tribute to Henson entitled Over Time that was shown as part of the 2005 Electronic Theater at SIGGRAPH.

- Henson was featured in the Boyz II Men video, "It's So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday."

- Henson featured in The American Adventure in Epcot at the Walt Disney World Resort.

- Vintage footage of Henson was featured in an American Express credit card commercial in 2008.

- Philip Roth often quotes Jim Henson in his Sabbath's Theater as the "great regret" for Mickey Sabbath.

[edit] References

[edit] Bibliography

- Finch, Christopher (1981). Of Muppets and Men: The Making of The Muppet Show'. New York: Muppet Press/Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-52085-8.

- Finch, Christopher (1993). Jim Henson: The Works—The Art, the Magic, the Imagination. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-41203-4.

[edit] Notes

- ^ HowStuffWorks.com

- ^ The Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Recipients List

- ^ a b c Padgett, John B.. "Jim Henson". The Mississippi Writers Page. University of Mississippi Department of English. 1999-02-17. http://www.olemiss.edu/mwp/dir/henson_jim/index.html. Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schindehette, Susan; Podolsky, J.D (1990-06-18). "Legacy of a Gentle Genius" (reprint). People. http://www.muppetcentral.com/articles/tributes/henson/hensonarticle5.shtml. Retrieved on 2007-05-06.

- ^ a b c d e Blau, Eleanor (1990-05-17). "Jim Henson, Puppeteer, Dies; The Muppets’ Creator Was 53". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CE5DF163BF934A25756C0A966958260. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

- ^ Finch (1993). p. 9.

- ^ Finch (1993). p. 102.

- ^ a b Collins, James (1998-06-08). "Time 100: Jim Henson". TIME. http://www.time.com/time/time100/artists/profile/henson.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

- ^ a b "The Man Behind the Frog". TIME. 1978-12-25. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,948401,00.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris, Judy (1998-09-21). "Muppet Master: An Interview with Jim Henson". Muppet Central. http://www.muppetcentral.com/articles/interviews/jim1.shtml. Retrieved on 2007-05-05.

- ^ a b Finch (1993). p. 22.

- ^ Plume, Kenneth. "Interview with Frank Oz". IGN FilmForce. IGN, 2000-02-10. http://movies.ign.com/articles/035/035842p1.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-06.

- ^ Freeman, Don (1979). "Muppets On His Hands". The Saturday Evening Post 251.8. pp. 50–53, 126.

- ^ a b c d Harrigan, Stephen (July 1990). "It’s Not Easy Being Blue" (reprint). LIFE. http://www.muppetcentral.com/articles/tributes/henson/hensonarticle6.shtml. Retrieved on 2007-05-06.

- ^ Shales, Tom; Miller, James Andrew (2002). Live From New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 79–80. ISBN 0-316-78146-0.

- ^ Skow, John (1978-12-25). "Those Marvelous Muppets". TIME. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,948400,00.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

- ^ Seligmann, J.; Leonard, E. (1990-05-28). "Jim Henson: 1936–1990". Newsweek.

- ^ Finch (1993). p. 128.

- ^ "The Muppet Movie", Box Office Mojo. Retrieved on 2007-07-11.

- ^ Finch (1993). p. 176.

- ^ "1984 Yearly Box Office Results", Box Office Mojo. Retrieved on 2007-07-11.

- ^ Darnton, Nina (1986-06-27). "Jim Henson's "Labyrinth"". The New York Times. http://movies2.nytimes.com/mem/movies/review.html?res=9A0DE5DC1139F934A15755C0A960948260. Retrieved on 2007-05-06.

- ^ Sparrow, A.E.. "Return to Labyrinth Vol. 1 Review". IGN.com. http://comics.ign.com/articles/732/732053p1.html. 2006-09-11. Retrieved on 2007-07-10.

- ^ a b "Dialogue on Film: Jim Henson". American Film (American Film Institute): pp. 18–21. November 1989.

- ^ Kahn, Eve M. "All in the Modern Stone Age Family", The New York Times (Apr. 14, 1991). Accessed Feb. 20, 2009.

- ^ Owen, David. "Looking Out for Kermit", The New Yorker (Aug. 16, 1993.)

- ^ Angier, Natalie (1990-05-17). "An Aggressive Infection, Abrupt and Overwhelming". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CEFD6113BF934A25756C0A966958260. Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

- ^ Altman, Lawrence (1990-05-29). "The Doctor's World; Henson Death Shows Danger of Pneumonia". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CE7D6133BF93AA15756C0A966958260&sec=health&spon=&pagewanted=all. Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

- ^ Blau, Eleanor (1990-05-22). "Henson Is Remembered as a Man With Artistry, Humanity and Fun". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CE2DF143CF931A15756C0A966958260. Retrieved on 2007-05-14.

- ^ a b Barry, Chris. "Saying "Goodbye" to Jim". JimHillMedia.com. http://jimhillmedia.com/blogs/chris_barry/archive/2005/09/08/1722.aspx. 2005-09-08. Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

- ^ Curtis, Richard (screenwriter). Love Actually audio commentary [DVD]. 2004-04-24.

- ^ http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=2210&FLid=16911114&FLgrid=2210&

- ^ Plume, Kenneth (1999-07-19). "Ratting Out: An Interview with Muppeteer Steve Whitmire". Muppet Central. http://www.muppetcentral.com/articles/interviews/whitmire3.shtml. Retrieved on 2007-07-11.

- ^ Meier, Barry (2004-02-18). "Kermit and Miss Piggy Join Stable of Walt Disney Stars". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9905EFDE123DF93BA25751C0A9629C8B63. Retrieved on 2008-04-08.

- ^ "Empire Film Group Acquires Rights to Jim Henson Screenplay", Empire Film Group Press & Publicity, 2008-02-04. Retrieved on 2008-02-07.His wife had an affair with his sister for five years; which caused dramatic stress

- ^ "Jim Henson Statue & Memorial FAQ". UMD Newsdesk. University of Maryland. 2004-07-28. http://www.newsdesk.umd.edu/images/Henson/Articles/FAQ.html. Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Jim Henson |

- The Jim Henson Legacy

- Jim Henson at the Internet Movie Database

- Muppet Wiki: Jim Henson

- Art Directors Club biography and portrait

- The Jim Henson Works at the University of Maryland: 70+ digital videos available to students, scholars and visitors at the University of Maryland (College Park, MD)

- TIME 100: The Most Important People of the Century (Artists & Entertainers)

- Jim Henson on Muppet Wiki, an external wiki

|

||||||||