Photorealism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Look up photo-realism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

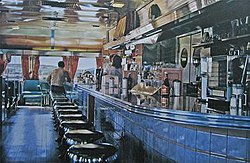

Photorealism is the genre of painting based on making a painting of a photograph. The term is primarily applied to paintings from the United States photorealism art movement that began in the late 1960s, early 1970s. More recently, a splinter art movement called hyperrealism has developed.

Contents |

[edit] Style and history

As a full-fledged art movement, Photorealism evolved from Pop Art[1][2] and as a counter to Abstract Expressionism[3][4] as well as Minimalist art movements[5][6][7] [8] in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the United States.[9] It is also sometimes labeled as Super-Realism, New Realism, Sharp Focus Realism, or Hyper-Realism.[10] The Photorealist genre is predominately made up of painters. The word Photorealism was coined by Louis K. Meisel in 1968 and appeared in print for the first time in 1970 in a Whitney Museum catalogue for the show "Twenty-two Realists."[11]

Louis K. Meisel, two years later, developed a five-point definition at the request of Stuart M. Speiser, who had commissioned a large collection of works by the Photorealists, which later developed into a traveling show known as "Photo-Realism 1973: The Stuart M. Speiser Collection," which was donated to the Smithsonian in 1978 and is shown in several of its museums as well as traveling under the auspices of SITE.[12] The definition was as follows:

1. The Photo-Realist uses the camera and photograph to gather information.

2. The Photo-Realist uses a mechanical or semimechanical means to transfer the information to the canvas.

3. The Photo-Realist must have the technical ability to make the finished work appear photographic.

4. The artist must have exhibited work as a Photo-Realist by 1972 to be considered one of the central Photo-Realists.

5. The artist must have devoted at least five years to the development and exhibition of Photo-Realist work.[13]

Photorealist painting cannot exist without the photograph. In Photorealism, change and movement must be frozen in time which must then be accurately represented by the artist.[14] Photorealists gather their imagery and information with the camera and photograph. Once the photograph is developed (usually onto a photographic slide) the artist will systematically transfer the image from the photographic slide onto canvases. This is done by either projecting the slide or grid techniques.[15] The resulting images are often direct copies of the original photograph but are usually larger than the original photograph or slide. This results in the photorealist style being tight and precise, often with an emphasis on imagery that requires a high level of technical prowess and virtuosity to simulate, such as reflections in specular surfaces and the geometric rigor of man-made environs.[16]

20th century photorealism can be contrasted with the similarly literal style found in trompe l'oeil paintings of the 19th century. However, trompe l'oeil paintings tended to be carefully designed, very shallow-space still-lifes, employing illusionistic devices such as the use of shadows to cause small objects to appear to exist above the surface of the painting. (Trompe l'oeil literally means "fool the eye.") The photorealism movement moved beyond this illusionism to tackle deeper spatial representations (e.g. urban landscapes) and took on much more varied and dynamic subject matter.

[edit] Artists

The first generation of American photorealists includes such painters as Richard Estes, Ralph Goings, Howard Kanovitz, Chuck Close, Charles Bell, Audrey Flack, Don Eddy, Robert Bechtle, Tom Blackwell, and Richard McLean.[17] Duane Hanson and John DeAndrea were the sculptors associated with photorealism famous for amazingly life-like painted sculptures of average people that were complete with simulated hair and real clothes. They were called Verists.[17] Often working independently of each other and with widely different starting points, photorealists routinely tackled mundane or familiar subjects in traditional art genres--landscapes (mostly urban rather than naturalistic), portraits, and still lifes. They essentially evolved from Pop art and carried Pop Art's return to imagery to its ultimate possibilities.[17]

[edit] At the Millennium

The height of the original photorealism movement was in the mid-1970s but the early 1990s saw a re-birth of interest in the genre. This renewed interest included original artists from the "first generation" as well as many younger photorealists. The evolution of photorealism brought an emergence of an advanced form of photorealistic painting; sometimes known as "Hyperrealism."[18] With the new technology in cameras and digital equipment, these artists are able to be far more precision-oriented than their predecessors. Although the original tradition of Photorealism is a frame of reference for the artists, they incorporate more detailed references in their work by use of better technology.[18] Many of the new Photorealists are building upon the foundation set by the original photorealists and the likenesses of their predecessors can be seen in such works by Photorealists Clive Head, Glennray Tutor, Kim Mendenhall, Raphaella Spence, Bertrand Meniel, Roberto Bernardi, Gottfried Helnwein, Bernardo Torrens, and Tony Brunelli.[18][19] The re-birth of Photorealism has been apparent in both the United States and Europe with the Internet being a huge factor in the spread of the genre.[18]

[edit] List of Photorealists

[edit] Original photorealists

[edit] Photorealists

[edit] References

[edit] Notes

- ^ Chase, Linda, Photorealism at the Millennium, The Not-So-Innocent Eye: Photorealism in Context. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 2002. pp 14-15.

- ^ Nochlin, Linda, The Realist Criminal and the Abstract Law II, Art In America. 61 (November - December 1973), P. 98.

- ^ Chase, Linda, Photorealism at the Millennium, The Not-So-Innocent Eye: Photorealism in Context. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 2002. pp 14-15.

- ^ Nochlin, Linda, The Realist Criminal and the Abstract Law II, Art In America. 61 (November - December 1973), P. 98.

- ^ Fleming, John and Honour, Hugh The Visual Arts: A History, 3rd Edition. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 1991. p. 709

- ^ Chase, Linda, Photorealism at the Millennium, The Not-So-Innocent Eye: Photorealism in Context. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 2002. pp 14-15.

- ^ Nochlin, Linda, The Realist Criminal and the Abstract Law II, Art In America. 61 (November - December 1973), P. 98.

- ^ Battock, Gregory. Preface to Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York, 1980. pp 8-10.

- ^ Battock, Gregory. Preface to Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York, 1980. pp 8-10.

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980. p. 12.

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980. p. 12.

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980. p. 12.

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980. p. 13.

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980. p. 13.

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980. p. 14.

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980. p. 15.

- ^ a b c Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980.

- ^ a b c d Chase, Linda, Photorealism at the Millennium, The Not-So-Innocent Eye: Photorealism in Context. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 2002.

- ^ Wilmerding, John. Richard Estes. Rizzoli. New York, 2006.

[edit] General References

- Photorealism by Louis K. Meisel. Abradale/Abrams, New York, NY, (1989). ISBN 978-0 810980921

- Photorealism Since 1980 by Louis K. Meisel. Harry N. Abrams, New York, NY, (1993). ISBN 978-0810937208

- Photorealism at the Millennium by Louis K. Meisel and Linda Chase. Harry N. Abrams, New York, NY, (2002). ISBN 978-0810934832

- Photorealism: The Liff Collection edited by Linda Chase. Naples Museum of Art, Naples, FL, (2001). ISBN 978-0970515810

- Charles Bell: The Complete Works, 1970-1990 by Henry Geldzahler, Louis K. Meisel, Abrams New York, NY, (1991). ISBN 978-0810931141

- Richard Estes: The Complete Paintings, 1966-1985 by Louis K. Meisel, John Perreault, Abrams New York, NY, (1986). ISBN 978-0810908816

- Richard Estes, by John Wilmerding. Rizzoli, New York, NY, (2006). ISBN 978-0847828074

- Robert Bechtle: A Retrospective by Michael Auping, Janet Bishop, Charles Ray, and Jonathan Weinberg. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, (2005). ISBN 978-0520245433

- Ralph Goings: Essay/Interview by Linda Chase. Harry N. Abrams, New York, NY, (1988). ISBN 978-0810910300

- Peinture et Photographie by Jean-Luc Chalumeau. Chêne, Paris, (2007). ISBN 978-284277731X

[edit] External links

- The Arts Trust

- Louis K. Meisel Gallery

- O.K. Harris Gallery

- Richard Estes information

- Chuck Close Online

- Ralph Goings' website

- John Baeder

- Audrey Flack's website

- Neil MacCormick

- Robert Neffson's Website

- Nathan Walsh

- Rod Penner

- [http://www.denispeterson.com/ Denis Peterson

- Clive Head

- Chiara Albertoni

- Bernardo Torrens

- Charles Bell