On the Jews and Their Lies

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

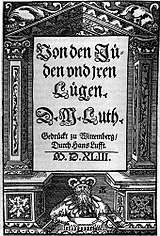

On the Jews and Their Lies (German: Von den Jüden und iren Lügen; in modern spelling Von den Juden und ihren Lügen) is a 65,000-word treatise written by German Reformation leader Martin Luther in 1543.

The treatise is a polemic condemning the Jewish religion from a Christian viewpoint. Luther writes that those who continue to adhere to Judaism are a "base, whoring people, that is, no people of God, and their boast of lineage, circumcision, and law must be accounted as filth."[1] Luther wrote that they are "full of the devil's feces ... which they wallow in like swine,"[2] and the synagogue is an "incorrigible whore and an evil slut ..."[3] He argues that their synagogues and schools be set on fire, their prayer books destroyed, rabbis forbidden to preach, homes razed, and property and money confiscated. They should be shown no mercy or kindness,[4] afforded no legal protection,[5] and these "poisonous envenomed worms" should be drafted into forced labor or expelled for all time.[6] He also seems to tolerate the murder of Jews, writing "[w]e are at fault in not slaying them."[7]

The formerly prevailing scholarly view[8] since the Second World War is that the treatise exercised a major influence on Germany's attitude toward its Jewish citizens in the centuries between the Reformation and the Holocaust. Four hundred years after it was written, the National Socialists displayed On the Jews and Their Lies during Nuremberg rallies, and the city of Nuremberg presented a first edition to Julius Streicher, editor of the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, the newspaper describing it as the most radically antisemitic tract ever published.[9] Against this view, theologian Johannes Wallmann writes that the treatise had no continuity of influence in Germany, and was in fact largely ignored during the 18th and 19th centuries.[10] Hans Hillerbrand argues that to focus on Luther's role in the development of German antisemitism is to underestimate the "larger peculiarities of German history."[11]. Scottish history of empire author Niall Ferguson observes in his 2006 work The War of the World that by the 1930s Germany's Jews were among the most integrated in Europe, a view that accords with the use of images from the Polish Ghetto to attack 'disguised' German Jews in the anti-semitic film The Eternal Jew. Unlike the Nazis, Luther did not hold that the Jewish race was inferior, only that the Jewish religion refused to recognise Jesus as the Messiah.[citation needed]

Since the 1980s, some Lutheran church bodies have formally denounced and dissociated themselves from Luther's writings on the Jews. In November 1998, on the 60th anniversary of Kristallnacht, the Lutheran Church of Bavaria issued a statement: "It is imperative for the Lutheran Church, which knows itself to be indebted to the work and tradition of Martin Luther, to take seriously also his anti-Jewish utterances, to acknowledge their theological function, and to reflect on their consequences. It has to distance itself from every [expression of] anti-Judaism in Lutheran theology."[12]

Contents |

[edit] Evolution of Luther's views

Luther's attitude toward the Jews changed over his life. In his earlier period, until around 1536, he expressed concern for their situation and was enthusiastic at the prospect of converting them to Christianity, but in his later period, he denounced them and urged their harsh persecution and even seemed to accept their murder as guiltless.[13]

Michael Berenbaum writes that Luther's reliance on the Bible as the sole source of Christian authority fed his later fury toward Jews over their rejection of Jesus as the messiah.[14] For Luther, salvation depended on the belief that Jesus was the Son of God, a belief that adherents of Judaism do not share. Early in his life, Luther had argued that the Jews had been prevented from converting to Christianity by the proclamation of what he believed to be an impure gospel by the Catholic Church, and he believed they would respond favorably to the evangelical message if it were presented to them gently. He expressed concern for the poor conditions in which they were forced to live, and insisted that anyone denying that Jesus was born a Jew was committing heresy.[14]

Luther's first known comment on the Jews is in a letter written to Reverend Spalatin in 1514:

| “ | Conversion of the Jews will be the work of God alone operating from within, and not of man working — or rather playing — from without. If these offences be taken away, worse will follow. For they are thus given over by the wrath of God to reprobation, that they may become incorrigible, as Ecclesiastes says, for every one who is incorrigible is rendered worse rather than better by correction. [15] | ” |

Graham Noble writes that Luther wanted to save Jews, in his own terms, not exterminate them, but beneath his apparent reasonableness toward them, there was a "biting intolerance," which produced "ever more furious demands for their conversion to his own brand of Christianity" (Noble, 1-2). When they failed to convert, he turned on them.[16]

In 1519 Luther challenged the doctrine Servitus Judaeorum ("Servitude of the Jews"), established in Corpus Juris Civilis by Justinian I in 529. He wrote: "Absurd theologians defend hatred for the Jews. ... What Jew would consent to enter our ranks when he sees the cruelty and enmity we wreak on them—that in our behavior towards them we less resemble Christians than beasts?" [17]

In his commentary on the Magnificat, Luther is critical of the emphasis Judaism places on the Torah, the first five books of the Old Testament. He states that they "undertook to keep the law by their own strength, and failed to learn from it their needy and cursed state." [18] Yet, he concludes, that God's grace will continue for Jews as Abraham's descendants for all time, since they may always become Christians. [19] "We ought...not to treat the Jews in so unkindly a spirit, for there are future Christians among them." [20]

In his 1523 essay That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew, Luther condemned the inhuman treatment of the Jews and urged Christians to treat them kindly. Luther's fervent desire was that Jews would hear the Gospel proclaimed clearly and be moved to convert to Christianity. Thus he argued:

| “ | If I had been a Jew and had seen such dolts and blockheads govern and teach the Christian faith, I would sooner have become a hog than a Christian. They have dealt with the Jews as if they were dogs rather than human beings; they have done little else than deride them and seize their property. When they baptize them they show them nothing of Christian doctrine or life, but only subject them to popishness and monkery...If the apostles, who also were Jews, had dealt with us Gentiles as we Gentiles deal with the Jews, there would never have been a Christian among the Gentiles ... When we are inclined to boast of our position [as Christians] we should remember that we are but Gentiles, while the Jews are of the lineage of Christ. We are aliens and in-laws; they are blood relatives, cousins, and brothers of our Lord. Therefore, if one is to boast of flesh and blood the Jews are actually nearer to Christ than we are...If we really want to help them, we must be guided in our dealings with them not by papal law but by the law of Christian love. We must receive them cordially, and permit them to trade and work with us, that they may have occasion and opportunity to associate with us, hear our Christian teaching, and witness our Christian life. If some of them should prove stiff-necked, what of it? After all, we ourselves are not all good Christians either. [21] | ” |

A few years later, in 1528, Luther reported an epic bout of diarrhea brought on by his consumption of Kosher food. In a letter to Melancthon, Luther suggested that the Jewish community had attempted to poison him. Luther further suggested that Kosher foods, which he believed to be disagreeable with the constitution of Gentiles, were eaten by the Jews (who, presumably, would not experience adverse effects from their consumption) as a show of superiority over the Gentiles and as a means of separating themselves from the mainstream German culture. He suggested that Kosher foods be banned from Christian nations.[citation needed]

In August 1536 Luther's prince, Elector of Saxony John Frederick, issued a mandate that prohibited Jews from inhabiting, engaging in business in, or passing through his realm. An Alsatian shtadlan, Rabbi Josel of Rosheim, asked a reformer Wolfgang Capito to approach Luther in order to obtain an audience with the prince, but Luther refused every intercession. [22] In response to Josel, Luther referred to his unsuccessful attempts to convert the Jews: "... I would willingly do my best for your people but I will not contribute to your [Jewish] obstinacy by my own kind actions. You must find another intermediary with my good lord." [23] Heiko Oberman notes this event as significant in Luther’s attitude toward the Jews: "Even today this refusal is often judged to be the decisive turning point in Luther’s career from friendliness to hostility toward the Jews." [24]

Paul Johnson writes that "Luther was not content with verbal abuse. Even before he wrote his anti-Semitic pamphlet, he got Jews expelled from Saxony in 1537, and in the 1540s he drove them from many German towns; he tried unsuccessfully to get the elector to expel them from Brandenburg in 1543."[25]

[edit] On the Jews and Their Lies

Luther read Der gantze Jüdisch Glaub (The Whole Jewish Belief) in 1539.[27] The antisemitic book had been published in 1530 by Anton Margaritha, a convert from Judaism to Christianity who had become a Lutheran. Josel of Rosheim held a public debate with Margaritha in the same year before Charles V and his court at Augsburg at which Josel was decisively victorious, resulting in Margaritha's expulsion from the Empire.[28]

It is believed that Luther was influenced by Margaritha's book in Luther's On the Jews and Their Lies, written in 1543, three years before his death. In his book, Luther recommends that Jews be deprived of money, civil rights, religious teaching, and education, and that they be forced to labor on the land, or else be expelled from Germany and possibly killed.

- I had made up my mind to write no more either about the Jews or against them. But since I learned that these miserable and accursed people do not cease to lure to themselves even us, that is, the Christians, I have published this little book, so that I might be found among those who opposed such poisonous activities of the Jews who warned the Christians to be on their guard against them.[29]

Luther stated in his introductory remarks that he was writing in response to a pamphlet, unidentified by historians, written by an unidentified Jew or Jews, sent to him by Count Wolfgang Schlick of Falkenau:

- Dear sir and good friend[30], I have received a treatise in which a Jew engages in dialog with a Christian. He dares to pervert the scriptural passages which we cite in testimony to our faith, concerning our Lord Christ and Mary his mother, and to interpret them quite differently. With this argument he thinks he can destroy the basis of our faith.[31]

He refers to Jews as "a brood of vipers and children of the devil" (from Matthew 12:34), "miserable, blind, and senseless," "truly stupid fools," "thieves and robbers," "lazy rogues," "daily murderers," and "vermin," and likens them to "gangrene." He then goes on to recommend that Jewish synagogues and schools be burned, their homes razed and destroyed, their writings confiscated, their rabbis forbidden to teach, their travel restricted, that lending money be outlawed for them, and that they be forced to earn their wages in farming. Luther advised "[i]f we wish to wash our hands of the Jews' blasphemy and not share in their guilt, we have to part company with them. They must be driven from our country" and "we must drive them out like mad dogs."

In conclusion, he wrote:

- There is no other explanation for this than the one cited earlier from Moses — namely, that God has struck [the Jews] with 'madness and blindness and confusion of mind.' So we are even at fault in not avenging all this innocent blood of our Lord and of the Christians which they shed for three hundred years after the destruction of Jerusalem, and the blood of the children they have shed since then (which still shines forth from their eyes and their skin). We are at fault in not slaying them. Rather we allow them to live freely in our midst despite all their murdering, cursing, blaspheming, lying, and defaming; we protect and shield their synagogues, houses, life, and property. In this way we make them lazy and secure and encourage them to fleece us boldly of our money and goods, as well as to mock and deride us, with a view to finally overcoming us, killing us all for such a great sin, and robbing us of all our property (as they daily pray and hope). Now tell me whether they do not have every reason to be the enemies of us accursed Goyim, to curse us and to strive for our final, complete, and eternal ruin! [32]

Luther advocated an eight-point plan to get rid of the Jews either by religious conversion or by expulsion:

- "First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them. ..."

- "Second, I advise that their houses also be razed and destroyed. ..."

- "Third, I advise that all their prayer books and Talmudic writings, in which such idolatry, lies, cursing and blasphemy are taught, be taken from them. ..."

- "Fourth, I advise that their rabbis be forbidden to teach henceforth on pain of loss of life and limb. ..."

- "Fifth, I advise that safe-conduct on the highways be abolished completely for the Jews. ..."

- "Sixth, I advise that usury be prohibited to them, and that all cash and treasure of silver and gold be taken from them. ... Such money should now be used in ... the following [way]... Whenever a Jew is sincerely converted, he should be handed [a certain amount]..."

- "Seventh, I commend putting a flail, an ax, a hoe, a spade, a distaff, or a spindle into the hands of young, strong Jews and Jewesses and letting them earn their bread in the sweat of their brow... For it is not fitting that they should let us accursed Goyim toil in the sweat of our faces while they, the holy people, idle away their time behind the stove, feasting and farting, and on top of all, boasting blasphemously of their lordship over the Christians by means of our sweat. No, one should toss out these lazy rogues by the seat of their pants."

- "If we wish to wash our hands of the Jews' blasphemy and not share in their guilt, we have to part company with them. They must be driven from our country" and "we must drive them out like mad dogs." [33]

Luther's arguments and accusations: Luther's first argument is that all races are equal, therefore the Jews should not boast about their lineage. [34]

- "there is no difference whatsoever with regard to birth or flesh and blood, as reason must tell us. Therefore" neither Jew nor Gentile should boast "before God of their physical birth . . . since we both partake of one birth, one flesh and blood, from the very first, best, and holiest ancestors. Neither one can reproach or upbraid the other about some peculiarity without implicating himself at the same time." (148).

In On the Jews and Their Lies, Luther made a number of accusations against the Jews:

- "In the first place, they defame our Lord Jesus Christ, calling him a sorcerer and tool of the devil.[35] This they do because they cannot deny his miracles. Thus they imitate their forefathers, who said, 'He casts out demons by Beelzebub, the prince of demons' Luke 11:15."[36]

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Luther, Martin. On the Jews and Their Lies, 154, 167, 229, cited in Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 111.

- ^ Obermann, Heiko. Luthers Werke. Erlangen 1854, 32:282, 298, in Grisar, Hartmann. Luther. St. Louis 1915, 4:286 and 5:406, cited in Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 113.

- ^ Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 112.

- ^ Michael, Robert. "Luther, Luther Scholars, and the Jews," Encounter 46:4, (Autumn 1985), p. 342.

- ^ Michael, Robert. "Luther, Luther Scholars, and the Jews," Encounter 46:4, (Autumn 1985), p. 343.

- ^ Luther, Martin. On the Jews and Their Lies, Trans. Martin H. Bertram, in Luther's Works. (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971).

- ^ Luther, Martin. On the Jews and Their Lies, cited in Robert Michael. "Luther, Luther Scholars, and the Jews," Encounter 46 (Autumn 1985) No. 4:343-344.

- ^

- Wallmann, Johannes. "The Reception of Luther's Writings on the Jews from the Reformation to the End of the 19th Century", Lutheran Quarterly, n.s. 1 (Spring 1987) 1:72-97. Wallmann writes: "The assertion that Luther's expressions of anti-Jewish sentiment have been of major and persistent influence in the centuries after the Reformation, and that there exists a continuity between Christian anti-Judaism and modern racially oriented antisemitism, is at present wide-spread in the literature; since the Second World War it has understandably become the prevailing opinion."

- Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006; see chapter 4 "The Germanies from Luther to Hitler," pp. 105-151.

- Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007. Hillerbrand writes: "[H]is strident pronouncements against the Jews, especially toward the end of his life, have raised the question of whether Luther significantly encouraged the development of German antisemitism. Although many scholars have taken this view, this perspective puts far too much emphasis on Luther and not enough on the larger peculiarities of German history."

- ^ Ellis, Marc H. Hitler and the Holocaust, Christian Anti-Semitism", Baylor University Center for American and Jewish Studies, Spring 2004, slide 14. Also see Nuremberg Trial Proceedings, Vol. 12, p. 318, Avalon Project, Yale Law School, April 19, 1946.

- ^ Wallmann, Johannes. "The Reception of Luther's Writings on the Jews from the Reformation to the End of the 19th Century", Lutheran Quarterly, n.s. 1, Spring 1987, 1:72-97.

- ^ Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007.

- ^ "Christians and Jews: A Declaration of the Lutheran Church of Bavaria", November 24, 1998, also printed in Freiburger Rundbrief, 6:3 (1999), pp.191-197. For other statements from Lutheran bodies, see:

- "Q&A: Luther's Anti-Semitism", Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod;

- "Declaration of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America to the Jewish Community", Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, April 18, 1994;

- "Statement by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada to the Jewish Communities in Canada", Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada, July 12-16, 1995;

- "Time to Turn", The Evangelical [Protestant] Churches in Austria and the Jews. Declaration of the General Synod of the Evangelical Church A.B. and H.B., October 28, 1998.

- ^ "Luther, Martin", JewishEncyclopedia.com. See also the note supra referring to Robert Michael.

- ^ a b Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Martin Luther, "Luther to George Spalatin," in Luther's Correspondence and Other Contemporaneous Letters, trans. Henry Preserved Smith (Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society, 1913), 1:29.

- ^ Michael, Robert. "Luther, Luther Scholars, and the Jews," Encounter 46 (Autumn 1985) No. 4:343-344.)

- ^ Luther quoted in Elliot Rosenberg, But Were They Good for the Jews? (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1997), p.65.

- ^ Martin Luther, The Magnificat, Trans. A. T. W. Steinhaeuser, in Luther's Works (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1956), 21:354.

- ^ Russell Briese, "Martin Luther and the Jews," Lutheran Forum 34 (2000) No. 2:32.

- ^ Luther, Magnificat, 21:354f.

- ^ Martin Luther, "That Jesus Christ was Born a Jew," Trans. Walter I. Brandt, in Luther's Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1962), pp. 200-201, 229.

- ^ Martin Brecht, Martin Luther (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1985-1993), 3:336.

- ^ Luther’s letter to Rabbi Josel as cited by Gordon Rupp, Martin Luther and the Jews (London: The Council of Christians and Jews, 1972), 14. According to [1], this paragraph is not available in the English edition of Luther’s works.

- ^ Heiko Oberman, Luther: Man Between God and the Devil (New York: Image Books, 1989), p.293.

- ^ Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews, p. 242.

- ^ The references cited in the Passionary for this woodcut: 1 John 2:14-16, Matthew 10:8, and The Apology of the Augsburg Confession, Article 8, Of the Church

- ^ [2] p.18.

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ Luther's Works, Martin Bertram, trans., Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971, 47:137

- ^ Luther’s correspondent Count Schlick

- ^ Luther's Works, Martin Bertram, trans., Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971, 47:137.

- ^ Martin Luther, On the Jews and Their Lies, Trans. Martin H. Bertram, in Luther's Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971), 47:267.

- ^ Luther, On the Jews, 47:268-288, 292.

- ^ Page number citations are to Luther's Works, Vol. 47: The Christian in Society IV. (translated by M. Bertram) Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1999, ©1971.

- ^ "Most of these and the following charges are contained in the works of Margaritha and Porchetus which Luther had consulted (cf. Introduction), and beyond this, were part of the common medieval tradition. In many cases, the charges and countercharges are traceable to the earliest polemics between Jews and Christians in the first and second centuries." (Luther's Works, Vol. 47, footnote 159).

- ^ Luther, Martin: Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan (Hrsg.); Oswald, Hilton C. (Hrsg.); Lehmann, Helmut T. (Hrsg.) Trans. by Martin H. Bertram: Luther's Works, Vol. 47: The Christian in Society IV. Philadelphia : Fortress Press, 1999, ©1971, 47:256.

[edit] Bibliography

- Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1978. ISBN 0-687-16894-5.

- Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther, 3 vols. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1985-1993. ISBN 0-8006-0738-4, ISBN 0-8006-2463-7, ISBN 0-8006-2704-0.

- Gavriel, Mardell J. The Anti-Semitism of Martin Luther: A Psychohistorical Exploration. Ph.D. diss., Chicago School of Professional Psychology, 1996.

- Goldhagen, Daniel. Hitler's Willing Executioners. Vintage, 1997. ISBN 0-679-77268-5.

- Halpérin, Jean, and Arne Sovik, eds. Luther, Lutheranism and the Jews: A Record of the Second Consultation between Representatives of The International Jewish Committee for Interreligious Consultation and the Lutheran World Federation Held in Stockholm, Sweden, 11-13 July 1983. Geneva: LWF, 1984.

- Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-06-091533-1.

- Kaennel, Lucie. Luther était-il antisémite? (Luther: Was He an Antisemite?). Entrée Libre N° 38. Geneva: Labor et Fides, 1997. ISBN 2-8309-0869-4.

- Kittelson, James M. Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1986. ISBN 0-8066-2240-7.

- Luther, Martin. "On the Jews and Their Lies, 1543". Martin H. Bertram, trans. In Luther's Works. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971. 47:137-306.

- Oberman, Heiko A. The Roots of Anti-Semitism in the Age of Renaissance and Reformation. James I. Porter, trans. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984. ISBN 0-8006-0709-0.

- Rosenberg, Elliot, But Were They Good for the Jews? (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1997). ISBN 1-55972-436-6.

- Roynesdal, Olaf. Martin Luther and the Jews. Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 1986.

- Rupp, Gordon. Martin Luther: Hitler's Cause or Cure? In Reply to Peter F. Wiener. London: Lutterworth Press, 1945.

- Siemon-Netto, Uwe. The Fabricated Luther: the Rise and Fall of the Shirer Myth. Peter L. Berger, Foreword. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1995. ISBN 0-570-04800-1.

- Siemon-Netto, Uwe. "Luther and the Jews". Lutheran Witness 123 (2004)No. 4:16-19. (PDF)

- Steigmann-Gall, Richard. The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919-1945. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-82371-4.

- Tjernagel, Neelak S. Martin Luther and the Jewish People. Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House, 1985. ISBN 0-8100-0213-2.

- Wallmann, Johannes. "The Reception of Luther's Writings on the Jews from the Reformation to the End of the 19th Century." Lutheran Quarterly 1 (Spring 1987) 1:72-97.

- Wiener, Peter F. Martin Luther: Hitler's Spiritual Ancestor, Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 1945;[3]

[edit] External links

- Antisemitism - Reformation from the Florida Holocaust Museum.

- Luther and the Jews (PDF) by Siemon-Netto, Uwe. Lutheran Witness 123 (2004) No. 4:16-19.

- Martin Luther article in Jewish Encyclopedia (1906 ed.) by Gotthard Deutsch

- Martin Luther’s Attitude Toward The Jews by James Swan

- Martin Luther And The Jews by Mark Albrecht

- Luther's Letter to Bernhard, a Converted Jew (1523)

- The Jews and Their Lies (abridged English version published by CPA Book Publisher, Boring, Oregon at archive.org)

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||