The Birth of a Nation

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The Birth of a Nation | |

theatrical poster |

|

| Directed by | D. W. Griffith |

|---|---|

| Produced by | D. W. Griffith Harry Aitken[1] |

| Written by | T. F. Dixon, Jr. Frank E. Woods D.W. Griffith |

| Starring | Lillian Gish Henry B. Walthall Mae Marsh |

| Music by | Joseph Carl Breil |

| Cinematography | G.W. Bitzer |

| Editing by | D. W. Griffith Joseph Henabery James Smith Rose Smith Raoul Walsh |

| Distributed by | Epoch Film Co. |

| Release date(s) | 8 February 1915 (LA) |

| Running time | 190 minutes (at 16 frame/s) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent film English titles |

| Budget | $110,000 (est.) |

The Birth of a Nation (also known as The Clansman), is a 1915 silent film directed by D. W. Griffith; Set during and after the American Civil War, the film was based on Thomas Dixon's The Clansman, a novel and play. The Birth of a Nation is noted for its innovative technical and narrative achievements, and its status as the first Hollywood "blockbuster." It has provoked great controversy for its treatment of white supremacy and its positive portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan.[2]

Contents |

[edit] Plot

This silent film was originally presented in two parts separated by an intermission. Part 1 depicted pre-Civil War America, introducing two juxtaposed families: the Northern Stonemans, consisting of abolitionist Congressman Austin Stoneman (based on real-life Reconstruction-era Congressman Thaddeus Stevens), his two sons, and his daughter, Elsie, and the Southern Camerons, a family including two daughters (Margaret and Flora) and three sons, most notably Ben.

The Stoneman boys visit the Camerons at their South Carolina estate, representing the Old South. The eldest Stoneman boy falls in love with Margaret Cameron, and Ben Cameron idolizes a picture of Elsie Stoneman. When the Civil War begins, all the young men join their respective armies. A black militia (with a white leader) ransacks the Cameron house. The Cameron women are rescued when Confederate soldiers rout the militia. Meanwhile, the youngest Stoneman and two Cameron boys are killed in the war. Ben Cameron is wounded after a heroic battle in which he gains the nickname, "the Little Colonel," by which he is referred for the rest of the film. The Little Colonel is taken to a Northern hospital where he meets Elsie, who is working there as a nurse. The war ends and Abraham Lincoln is assassinated at Ford's Theater, allowing Austin Stoneman and other radical congressmen to punish the South for secession using radical measures supposedly typical of this period of the Reconstruction era.

Part 2 depicts Reconstruction. Stoneman and his mulatto protegé, Silas Lynch, go to South Carolina to observe their agenda of empowering Southern blacks via election fraud. Meanwhile, Ben, inspired by observing white children pretending to be ghosts to scare off black children, devises a plan to reverse perceived powerlessness of Southern whites by forming the Ku Klux Klan, although his membership in the group angers Elsie.

Then Gus, a former slave who has educated himself and gained a title of recognition through the army, proposes to marry Flora. Scared by Gus' hostile advances, she flees into the forest, pursued by Gus. Trapped on a precipice, Flora leaps to her death. In response, the Klan hunts Gus, lynches him, and leaves his corpse on Lieutenant Governor Silas Lynch's doorstep. In retaliation, Lynch orders a crackdown on the Klan. The Camerons flee from the black militia and hide out in a small hut, home to two former Union soldiers, who agree to assist their former Southern foes in defending their Aryan birthright, according to the caption.

Meanwhile, with Austin Stoneman gone, Lynch tries to force Elsie to marry him. Disguised Klansmen discover her situation and leave to get reinforcements. The Klan, now at full strength, rides to her rescue and takes the opportunity to disperse the rioting "crazed negroes." Simultaneously, Lynch's militia surrounds and attacks the hut where the Camerons are hiding, but the Klan saves them just in time. Victorious, the Klansmen celebrate in the streets, and the film cuts to the next election where the Klan successfully disenfranchises black voters and disarms the blacks. The film concludes with a double honeymoon of Phil Stoneman with Margaret Cameron and Ben Cameron with Elsie Stoneman. The final frame shows masses oppressed by a mythical god of war suddenly finding themselves at peace under the image of Christ. The final title rhetorically asks: "Dare we dream of a golden day when the bestial War shall rule no more? But instead-the gentle Prince in the Hall of Brotherly Love in the City of Peace."

[edit] Production

The film was based on Thomas Dixon's novels The Clansman and The Leopard's Spots. Griffith, whose father had served as a colonel in the Confederate Army, agreed to pay Thomas Dixon $10,000 for the rights to his play The Clansman. Since he ran out of money and could afford only $2,500 of the original option, Griffith offered Dixon 25 percent interest in the picture. Dixon reluctantly agreed. The film's unprecedented success made him rich. Dixon's proceeds were the largest sum any author had received for a motion picture story and amounted to several million dollars.

Griffith's budget started at US$40,000, but the film finally cost $112,000[3] (the equivalent of $2.2 million in 2007[4]). As a result, Griffith had to seek new sources of capital for his film. A ticket to the film cost a record $2 (the equivalent of $40 in 2007[4]). It remained the most profitable film of all time until it was dethroned by Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937.

West Point engineers provided technical advice on the Civil War battle scenes. They provided Griffith with the masses of artillery used in the film.[5]

The film premiered on February 8, 1915, at Clune's Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles.

At its premiere the film was entitled The Clansman but the title was later changed to The Birth of a Nation to reflect Griffith's belief that the United States emerged out of the American Civil War and Reconstruction, ostensibly ended by the Klan, as a unified nation.

[edit] Responses

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, founded in 1909, protested premieres of the film in numerous cities. It also conducted a public education campaign, publishing articles protesting the film's fabrications and inaccuracies, organizing petitions against it, and conducting education on the facts of the war and Reconstruction. [6]

When the film was shown, riots broke out in Boston, Philadelphia and other major cities. Chicago, Denver, Kansas City, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh and St. Louis refused to allow the film to open. The film's inflammatory character was a catalyst for gangs of whites to attack blacks. In Lafayette, Indiana, after seeing the movie, a white man murdered a black teenager. [7]

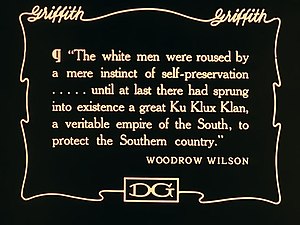

Thomas Dixon, author of the source play The Clansman, was a former classmate of President Woodrow Wilson at Johns Hopkins University. Dixon arranged a screening at the White House, for Wilson, members of his cabinet, and their families. Wilson was reported to have commented of the film that "it is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true". In Wilson: the new freedom, Arthur Link quotes Wilson's aide, Joseph Tumulty, who denied Wilson said this and also claims that "the President was entirely unaware of the nature of the play before it was presented and at no time has expressed his approbation of it."[8]

Relentless in publicizing the film, Dixon himself was apparently the source for the quotation, which has been repeated so often in print that it has taken on a separate life. Dixon went so far as to promote the film as "Federally endorsed". After controversy over the film had grown, Wilson wrote that he disapproved of the "unfortunate production."[9] D. W. Griffith would also respond to the film's negative critical reception with his next film Intolerance.

In 1918 Emmett J. Scott helped produce and John W. Noble directed The Birth of a Race in response. The film portrayed a positive image of blacks. Although the film was panned by white critics, it was well-received by black critics and moviegoers attending segregated theaters.[citation needed] Also in 1919, director/producer/writer Oscar Micheaux released Within Our Gates, another response. Notably, he reversed a key scene of Griffith's film by depicting a white man assaulting a black woman.

[edit] Ideology

The film is controversial due to its interpretation of history. University of Houston historian Steven Mintz summarizes its message as follows: Reconstruction was a disaster, blacks could never be integrated into white society as equals, and the violent actions of the Ku Klux Klan were justified to reestablish honest government.[10] The film suggested that the Ku Klux Klan restored order to the post-war South, which was depicted as endangered by abolitionists, freedmen, and carpetbagging Republican politicians from the North. This reflects the so-called Dunning School of historiography.

This version was vigorously disputed by W.E.B. Du Bois and other black historians upon its release, and most historians of all backgrounds today, who point out African Americans' loyalty and contributions during the Civil War years and Reconstruction, including the establishment of universal public education. Some historians, such as E. Merton Coulter in his The South Under Reconstruction (1947), maintained the Dunning School view after World War II. However, today this argument is largely seen as a product of Anglo-American racism of the early twentieth century, by which many Americans held that black Americans were unequal as citizens.

The civil rights movement and other social movements created a new generation of historians, such as leftist scholar Eric Foner, who led a reassessment of Reconstruction. Building on Du Bois' work but also adding new sources, they focused on achievements of the African American and white Republican coalitions, such as establishment of universal public education and charitable institutions in the South and extension of suffrage to black men. In response, the Southern-dominated Democratic Party and its affiliated white militias used extensive terrorism, intimidation and outright assassinations to suppress African-American leaders and voting in the 1870s and to regain power.[11]

[edit] Significance

Released in 1915, the film has been credited with securing the future of feature-length films (any film over 60 minutes in length), as well as solidifying the visual language of cinema.

In its day, it was the highest grossing film, taking in more than $10 million, according to the box cover of the Shepard version of the DVD (equivalent to $200 million in 2007).[4]

The website Rotten Tomatoes, which compiles reviews from various sources, indicates the film has a 100% "fresh" (positive) rating.[12]

In 1992 the United States Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry. Despite its controversial story, the film has been praised by film critics such as Roger Ebert, who said: "'The Birth of a Nation' is not a bad film because it argues for evil. Like Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, it is a great film that argues for evil. To understand how it does so is to learn a great deal about film, and even something about evil."[13]

According to a 2002 article in the Los Angeles Times, the film facilitated the refounding of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.[14] As late as the 1970s, the Ku Klux Klan continued to use the film as a recruitment tool.

American Film Institute recognition

[edit] Cast

[edit] Sequel

A sequel was released to theaters one year later, in 1916, called The Fall of a Nation. The film was directed by Thomas Dixon, who adapted it from the novel of the same name. The film has three acts and a prologue.[15] Despite its success in the foreign market, the film was not a success among the American audience[16] and is now considered a lost film.

[edit] In popular culture

In 2008, DJ Spooky remixed Griffith's film as Rebirth of a Nation.

David Robertson's novel Booth includes a passage in which the film is shown at the Old Grover's National Theatre in Washington in 1916, providing a key plot point.

In Forrest Gump, a scene is depicted with the title character's great grandfather as the lead klansman.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

[edit] Notes

- ^ D. W. Griffith: Hollywood Independent

- ^ MJ Movie Reviews - Birth of a Nation, The (1915) by Dan DeVore

- ^ William K. Everson, American Silent Film. New York: Da Capo Press, 1978, p. 78

- ^ a b c Consumer Price Index calculator at Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis website

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q. "When Hollywood's Big Guns Come Right From the Source." The New York Times, 10 June 2002.

- ^ NAACP - Timeline

- ^ The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow . Jim Crow Stories . The Birth of a Nation | PBS

- ^ Letter from J. M. Tumulty, secretary to President Wilson, to the Boston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, quoted in Link, Wilson.

- ^ Woodrow Wilson to Joseph P. Tumulty, April 28, 1915 in Wilson, Papers, 33:86.

- ^ Digital History

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War. New York: Farrar Strauss and Giroux, 2006, p. 150-154

- ^ "The Birth of a Nation Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment, Inc. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/birth_of_a_nation/. Retrieved on 2008-07-19.

- ^ rogerebert.com: The Birth of a Nation

- ^ A Painful Present as Historians Confront a Nation's Bloody Past

- ^ The Fall of a Nation (1916) at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ Slide, Anthony (2004). American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon. University Press of Kentucky. pp. p.102. ISBN 0813123283. http://books.google.com/books?id=Ng_fyVJVMz4C.

[edit] Bibliography

- Addams, Jane, in Crisis: A Record of Darker Races, X (May 1915), 19, 41, and (June 1915), 88.

- Brodie, Fawn M. Thaddeus Stevens, Scourge of the South (New York, 1959) p. 86-93. Corrects the historical record as to Dixon's false representation of Stevens in this film with regard to his racial views and relations with his housekeeper.

- Chalmers, David M. Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan (New York: 1965) p. 30 *Cook, Raymond Allen. Fire from the Flint: The Amazing Careers of Thomas Dixon (Winston-Salem, N.C., 1968).

- Franklin, John Hope, "Propaganda as History" pp. 10-23 in Race and History: Selected Essays 1938-1988 (Louisiana State University Press: 1989); first published in The Massachusetts Review 1979. Describes the history of the novel, The Clan and this film.

- Franklin, John Hope, Reconstruction After the Civil War, (Chicago, 1961) p. 5-7

- Korngold, Ralph, Thaddeus Stevens. A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great (New York: 1955) pp. 72-76. corrects Dixon's false characterization of Stevens' racial views and of his dealings with his housekeeper.

- Leab, Daniel J., From Sambo to Superspade, (Boston, 1975) p. 23-39

- New York Times, roundup of reviews of this film, March 7, 1915.

- The New Republica, II (March 20, 1915), 185

- Simkins, Francis B., "New Viewpoints of Southern Reconstruction," Journal of Southern History, V (February, 1939), pp. 49-61.

- Stokes, Melvyn, 'D. W. Griffith's "The Birth of a Nation": A History of "The Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time"' (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007). The latest study of the film's making and subsequent career.

- Williamson, Joel, After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina During Reconstruction (Chapel Hill, 1965). This book corrects Dixon's false reporting of Reconstruction, as shown in his novel, his play and this film.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Birth of a Nation |

- The Birth of a Nation at the Internet Movie Database

- The Birth of a Nation at the TCM Movie Database

- The Birth of a Nation at Allmovie

- Watch complete film on Internet Archive

- Detailed account of the movie

- "Art (and History) by Lightning Flash": The Birth of a Nation and Black Protest

- The Birth of a Nation on Roger Ebert's list of great movies

- The Birth of a Nation on filmsite.org, a web site offering comprehensive summaries of classic films

- The Myth of a Nation by Jonathan Lapper, challenging some of the "firsts" listed by film historians

- Souvenir Guide for The Birth of a Nation, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Literature

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||