Least squares

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The method of least squares or ordinary least squares (OLS) is used to approximately solve overdetermined systems. Least squares is often applied in statistical contexts, particularly regression analysis.

Least squares can be interpreted as a method of fitting data. The best fit in the least-squares sense is that instance of the model for which the sum of squared residuals has its least value, a residual being the difference between an observed value and the value given by the model. The method was first described by Carl Friedrich Gauss around 1794.[1] Least squares corresponds to the maximum likelihood criterion if the experimental errors have a normal distribution and can also be derived as a method of moments estimator. Regression analysis is available in most statistical software packages.

The discussion is presented in terms of polynomial functions but any function can be used in least-squares data fitting. For example, a Fourier series fit is optimal in the least-squares sense.

Contents |

[edit] History

[edit] Context

The method of least squares grew out of the fields of astronomy and geodesy as scientists and mathematicians sought to provide solutions to the challenges of navigating the Earth's oceans during the Age of Exploration. The accurate description of the behavior of celestial bodies was key to enabling ships to sail in open seas where before sailors had relied on land sightings to determine the positions of their ships.

The method was the culmination of several advances that took place during the course of the eighteenth century[2]:

- The combination of different observations taken under the same conditions as opposed to simply trying one's best to observe and record a single observation accurately. This approach was notably used by Tobias Mayer while studying the librations of the moon.

- The combination of different observations as being the best estimate of the true value; errors decrease with aggregation rather than increase, perhaps first expressed by Roger Cotes.

- The combination of different observations taken under different conditions as notably performed by Roger Joseph Boscovich in his work on the shape of the earth and Pierre-Simon Laplace in his work in explaining the differences in motion of Jupiter and Saturn.

- The development of a criterion that can be evaluated to determine when the solution with the minimum error has been achieved, developed by Laplace in his Method of Situation.

[edit] The method itself

Carl Friedrich Gauss is credited with developing the fundamentals of the basis for least-squares analysis in 1795 at the age of eighteen. Legendre was the first to publish the method, however.

An early demonstration of the strength of Gauss's method came when it was used to predict the future location of the newly discovered asteroid Ceres. On January 1, 1801, the Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi discovered Ceres and was able to track its path for 40 days before it was lost in the glare of the sun. Based on this data, it was desired to determine the location of Ceres after it emerged from behind the sun without solving the complicated Kepler's nonlinear equations of planetary motion. The only predictions that successfully allowed Hungarian astronomer Franz Xaver von Zach to relocate Ceres were those performed by the 24-year-old Gauss using least-squares analysis.

Gauss did not publish the method until 1809, when it appeared in volume two of his work on celestial mechanics, Theoria Motus Corporum Coelestium in sectionibus conicis solem ambientium. In 1829, Gauss was able to state that the least-squares approach to regression analysis is optimal in the sense that in a linear model where the errors have a mean of zero, are uncorrelated, and have equal variances, the best linear unbiased estimators of the coefficients is the least-squares estimators. This result is known as the Gauss–Markov theorem.

The idea of least-squares analysis was also independently formulated by the Frenchman Adrien-Marie Legendre in 1805 and the American Robert Adrain in 1808.

[edit] Problem statement

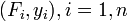

The objective consists of adjusting the parameters of a model function so as to best fit a data set. A simple data set consists of n points (data pairs)  , i = 1, ..., n, where

, i = 1, ..., n, where  is an independent variable and

is an independent variable and  is a dependent variable whose value is found by observation. The model function has the form

is a dependent variable whose value is found by observation. The model function has the form  , where the m adjustable parameters are held in the vector

, where the m adjustable parameters are held in the vector  . We wish to find those parameter values for which the model "best" fits the data. The least squares method defines "best" as when the sum, S, of squared residuals

. We wish to find those parameter values for which the model "best" fits the data. The least squares method defines "best" as when the sum, S, of squared residuals

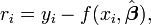

is a minimum. A residual is defined as the difference between the values of the dependent variable and the predicted values from the estimated model,

An example of a model is that of the straight line. Denoting the intercept as β0 and the slope as β1, the model function is given by

See the example of linear least squares for a fully worked out example of this model.

A data point may consist of more than one independent variable. For an example, when fitting a plane to a set of height measurements, the plane is a function of two independent variables, x and z, say. In the most general case there may be one or more independent variables and one or more dependent variables at each data point.

[edit] Solving the least squares problem

Least squares problems fall into two categories, linear and non-linear. The linear least squares problem has a closed form solution, but the non-linear problem does not and is usually solved by iterative refinement; at each iteration the system is approximated by a linear one, so the core calculation is similar in both cases.

The minimum of the sum of squares is found by setting the gradient to zero. Since the model contains m parameters there are m gradient equations.

and since  the gradient equations become

the gradient equations become

The gradient equations apply to all least squares problems. Each particular problem requires particular expressions for the model and its partial derivatives.

[edit] Linear least squares

A regression model is a linear one when the model comprises a linear combination of the parameters, i.e.

where the coefficients, φj, are functions of xi.

Letting

we can then see that in that case the least square estimate (or estimator, if we are in the context of a random sample),  is given by

is given by

For a derivation of this estimate see Linear least squares.

[edit] Non-linear least squares

There is no closed-form solution to a non-linear least squares problem. Instead, numerical algorithms are used to find the value of the parameters β which minimize the objective. Most algorithms involve choosing initial values for the parameters. Then, the parameters are refined iteratively, that is, the values are obtained by successive approximation.

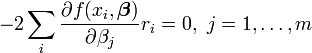

k is an iteration number and the vector of increments,  is known as the shift vector. In some commonly used algorithms, at each iteration the model may be linearized by approximation to a first-order Taylor series expansion about

is known as the shift vector. In some commonly used algorithms, at each iteration the model may be linearized by approximation to a first-order Taylor series expansion about

The Jacobian, J, is a function of constants, the independent variable and the parameters, so it changes from one iteration to the next. The residuals are given by

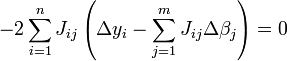

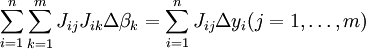

and the gradient equations become

which, on rearrangement, become m simultaneous linear equations, the normal equations.

The normal equations are written in matrix notation as

These are the defining equations of the Gauss–Newton algorithm.

[edit] Differences between linear and non-linear least squares

- The model function, f, in LLSQ (linear least squares) is a linear combination of parameters of the form

The model may represent a straight line, a parabola or any other polynomial-type function. In NLLSQ (non-linear least squares) the parameters appear as functions, such as β2,eβx and so forth. If the derivatives

The model may represent a straight line, a parabola or any other polynomial-type function. In NLLSQ (non-linear least squares) the parameters appear as functions, such as β2,eβx and so forth. If the derivatives  are either constant or depend only on the values of the independent variable, the model is linear in the parameters. Otherwise the model is non-linear.

are either constant or depend only on the values of the independent variable, the model is linear in the parameters. Otherwise the model is non-linear. - Many solution algorithms for NLLSQ require initial values for the parameters, LLSQ does not.

- Many solution algorithms for NLLSQ require that the Jacobian be calculated. Analytical expressions for the partial derivatives can be complicated. If analytical expressions are impossible to obtain the partial derivatives must be calculated by numerical approximation.

- In NLLSQ non-convergence (failure of the algorithm to find a minimum) is a common phenomenon whereas the LLSQ is globally concave so non-convergence is not an issue.

- NLLSQ is usually an iterative process. The iterative process has to be terminated when a convergence criterion is satisfied. LLSQ solutions can be computed using direct methods, although problems with large numbers of parameters are typically solved with iterative methods, such as the Gauss–Seidel method.

- In LLSQ the solution is unique, but in NLLSQ there may be multiple minima in the sum of squares.

- Under the condition that the errors are uncorrelated with the predictor variables, LLSQ yields unbiased estimates, but even under that condition NLLSQ estimates are generally biased.

These differences must be considered whenever the solution to a non-linear least squares problem is being sought.

[edit] Least squares, regression analysis and statistics

The methods of least squares and regression analysis are conceptually different. However, the method of least squares is often used to generate estimators and other statistics in regression analysis.

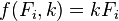

Consider a simple example drawn from physics. A spring should obey Hooke's law which states that the extension of a spring is proportional to the force, F, applied to it.

constitutes the model, where F is the independent variable. To estimate the force constant, k, a series of n measurements with different forces will produce a set of data,  , where yi is a measured spring extension. Each experimental observation will contain some error. If we denote this error

, where yi is a measured spring extension. Each experimental observation will contain some error. If we denote this error  , we may specify an empirical model for our observations,

, we may specify an empirical model for our observations,

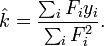

There are many methods we might use to estimate the unknown parameter k. Noting that the n equations for the m observations in our data comprise an overdetermined system with one unknown and n equations, we may choose to estimate k using least squares. The sum of squares to be minimized is

The least squares estimate of the force constant, k, is given by

Here it is assumed that application of the force causes the spring to expand and, having derived the force constant by least squares fitting, the extension can be predicted from Hooke's law.

In regression analysis the researcher specifies an empirical model. For example, a very common model is the straight line model which is used to test if there is a linear relationship between dependent and independent variable. If a linear relationship is found to exist, the variables are said to be correlated. However, correlation does not prove causation, as both variables may be correlated with other, hidden, variables, or the dependent variable may "reverse" cause the independent variables, or the variables may be otherwise spuriously correlated. For example, suppose there is a correlation between deaths by drowning and the volume of ice cream sales at a particular beach. Yet, both the number of people going swimming and the volume of ice cream sales increase as the weather gets hotter, and presumably the number of deaths by drowning is correlated with the number of people going swimming. Perhaps an increase in swimmers causes both the other variables to increase.

In order to make statistical tests on the results it is necessary to make assumptions about the nature of the experimental errors. A common (but not necessary) assumption is that the errors belong to a Normal distribution. The central limit theorem supports the idea that this is a good assumption in many cases.

- The Gauss–Markov theorem. In a linear model in which the errors have expectation zero conditional on the independent variables, are uncorrelated and have equal variances, the best linear unbiased estimator of any linear combination of the observations, is its least-squares estimator. "Best" means that the least squares estimators of the parameters have minimum variance. The assumption of equal variance is valid when the errors all belong to the same distribution.

- In a linear model, if the errors belong to a Normal distribution the least squares estimators are also the maximum likelihood estimators.

However, if the errors are not normally distributed, a central limit theorem often nonetheless implies that the parameter estimates will be approximately normally distributed so long as the sample is reasonably large. For this reason, given the important property that the error is mean independent of the independent variables, the distribution of the error term is not an important issue in regression analysis. Specifically, it is not typically important whether the error term follows a normal distribution.

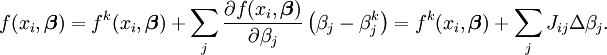

In a least squares calculation with unit weights, or in linear regression, the variance on the jth parameter, denoted  , is usually estimated with

, is usually estimated with

Confidence limits can be found if the probability distribution of the parameters is known, or an asymptotic approximation is made, or assumed. Likewise statistical tests on the residuals can be made if the probability distribution of the residuals is known or assumed. The probability distribution of any linear combination of the dependent variables can be derived if the probability distribution of experimental errors is known or assumed. Inference is particularly straightforward if the errors are assumed to follow a normal distribution, which implies that the parameter estimates and residuals will also be normally distributed conditional on the values of the independent variables.

[edit] Weighted least squares

- See also: Weighted mean

The expressions given above are based on the implicit assumption that the errors are uncorrelated with each other and with the independent variables and have equal variance. The Gauss–Markov theorem shows that, when this is so,  is a best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE). If, however, the measurements are uncorrelated but have different uncertainties, a modified approach might be adopted. Aitken showed that when a weighted sum of squared residuals is minimized,

is a best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE). If, however, the measurements are uncorrelated but have different uncertainties, a modified approach might be adopted. Aitken showed that when a weighted sum of squared residuals is minimized,  is BLUE if each weight is equal to the reciprocal of the variance of the measurement.

is BLUE if each weight is equal to the reciprocal of the variance of the measurement.

The gradient equations for this sum of squares are

which, in a linear least squares system give the modified normal equations

or

When the observational errors are uncorrelated the weight matrix, W, is diagonal. If the errors are correlated, the resulting estimator is BLUE if the weight matrix is equal to the inverse of the variance-covariance matrix of the observations.

When the errors are uncorrelated, it is convenient to simplify the calculations to factor the weight matrix as  . The normal equations can then be written as

. The normal equations can then be written as

where

For non-linear least squares systems a similar argument shows that the normal equations should be modified as follows.

Note that for empirical tests, the appropriate W is not known for sure and must be estimated. For this Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) techniques may be used.

[edit] Lasso method

In some contexts a regularized version of the least squares solution may be preferable. The LASSO algorithm, for example, finds a least-squares solution with the constraint that | β | 1, the L1-norm of the parameter vector, is no greater than a given value. Equivalently, it may solve an unconstrained minimization of the least-squares penalty with α | β | 1 added, where α is a constant. (This is the Lagrangian form of the constrained problem.) This problem may be solved using quadratic programming or more general convex optimization methods. The L1-regularized formulation is useful in some contexts due to its tendency to prefer solutions with fewer nonzero parameter values, effectively reducing the number of variables upon which the given solution is dependent [3].

[edit] See also

- L2 norm

- Least absolute deviation

- Measurement uncertainty

- Root mean square

- Squared deviations

- Iteratively re-weighted least squares

- Total least squares

- Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm

- Regression analysis

- Partial least squares regression

[edit] Notes

- ^ Bretscher, Otto (1995). Linear Algebra With Applications, 3rd ed.. Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice Hall.

- ^ Stigler, Stephen M. (1986). The History of Statistics: The Measurement of Uncertainty Before 1900. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- ^ Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. Royal. Statist. Soc B., Vol. 58, No. 1, pages 267–288

[edit] References

- Å. Björck, Numerical Methods for Least Squares Problems, SIAM, 1996 [1].

- C.R. Rao, H. Toutenburg, A. Fieger, C. Heumann, T. Nittner and S. Scheid, Linear Models: Least Squares and Alternatives, Springer Series in Statistics, 1999.

- T. Kariya, H. Kurata, Generalized Least Squares, Wiley, 2004.

- J. Wolberg, Data Analysis Using the Method of Least Squares: Extracting the Most Information from Experiments, Springer, 2005.

[edit] External links

- MIT Linear Algebra Lecture on Least Squares, from MIT OpenCourseWare

- Derivation of quadratic least squares

- Power Point Statistics Book -- Excellent slides providing an introductory regression example (University of Texas at Arlington)

|

||||||||||||||

![\hat{\text{var}}(\hat{\beta}_j)=\frac{S}{n-m}\left( \left[X^TX\right]^{-1}\right)_{jj}.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/f/e/a/fea70be68c2360badd21a309c208e08d.png)