AKS primality test

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The AKS primality test (also known as Agrawal-Kayal-Saxena primality test and cyclotomic AKS test) is a deterministic primality-proving algorithm created and published by three Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur computer scientists, Manindra Agrawal, Neeraj Kayal, and Nitin Saxena on August 6, 2002 in a paper titled PRIMES is in P.[1] The authors received many accolades, including the 2006 Gödel Prize and the 2006 Fulkerson Prize for this work.

The algorithm determines whether a number is prime or composite within polynomial time, and was soon improved by others. In 2005, Carl Pomerance and H. W. Lenstra, Jr. demonstrated a variant of AKS that runs in O(log6+ε(n)) operations where n is the number to be tested, a marked improvement over the initial O(log12+ε(n)) bound in the original algorithm [2].

Contents |

[edit] Importance

The key significance of AKS is that it was the first published primality-proving algorithm to be simultaneously general, polynomial, deterministic, and unconditional. Previous algorithms have achieved any three of these properties, but not all four.

- The AKS algorithm can be used to verify the primality of any general number given. Many fast primality tests are known that only work for numbers with certain properties. The Lucas–Lehmer test for Mersenne numbers only works for Mersenne numbers while Pépin's test can only be applied to Fermat numbers.

- The maximum running time of the algorithm can be expressed as a polynomial over the number of digits in the target number. ECPP and APR conclusively prove or disprove that a given number is prime, but are not known to have polynomial time bounds for all inputs.

- The algorithm guarantees to deterministically distinguish whether the target number is prime or composite. Randomized tests like Miller-Rabin and Baillie-PSW can test any given number for primality in polynomial time, but are known only to produce a probabilistic result.

- The correctness of AKS is not conditional on any subsidiary unproven hypothesis. In contrast, the Miller test is fully deterministic and runs in polynomial time over all inputs, but its correctness depends on the truth of the yet-unproven generalized Riemann hypothesis.

[edit] Concepts

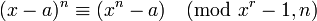

The AKS primality test is based upon the equivalence

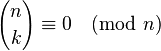

for a coprime to n, which is true if and only if n is prime. This is a generalization of Fermat's little theorem extended to polynomials and can be easily proven using the binomial theorem together with the following property of the binomial coefficient:

for all 0 < k < n if and only if n is prime.

for all 0 < k < n if and only if n is prime.

While this equivalence constitutes a primality test in itself, verifying it takes exponential time. Therefore AKS makes use of a related equivalence

which is the same as:

for some polynomials f and g. This equivalence can be checked in polynomial time, which is quicker than exponential time. Note that all primes satisfy this equivalence (choosing g = 0 in (3) gives (1), which holds for n prime). However, some composite numbers also satisfy the equivalence. The proof of correctness for AKS consists of showing that there exists a suitably small r and suitably small set of integers A such that if the equivalence holds for all such a in A then n must be prime.

[edit] Algorithm

The original[1] algorithm is as follows:

- Input: integer n > 1.

- If n = ab for integers a > 0 and b > 1, output composite.

- Find the smallest r such that or(n) > log2(n).

- If 1 < gcd(a,n) < n for some a ≤ r, output composite.

- If n ≤ r, output prime.

- For a = 1 to

do

do

- if (X+a)n≠ Xn+a (mod Xr − 1,n), output composite;

- Output prime.

Here or(n) is the multiplicative order of n modulo r. Furthermore, by log we mean the binary logarithm and  is Euler's totient function of r.

is Euler's totient function of r.

First of all, if n is a prime number, the algorithm will always return prime: since n is prime, steps 1. and 3. will never return composite. Step 5. will also never return composite because (2) is true for all prime numbers n. Therefore, the algorithm will return prime either in step 4. or step 6.

Conversely, if n is composite, the algorithm will always return composite: suppose the algorithm returns prime, then this will happen in either step 4. or step 6. In the first case, since n ≤ r, n has a factor a ≤ r such that 1 < gcd(a,n) < n, which would return composite. The remaining possibility is that the algorithm returns prime in step 6. In the original article[1] it is proven that this will not happen, because the multiple equalities tested in step 5. are sufficient to guarantee that the output is composite.

Proving that the algorithm is correct is achieved by proving two key facts, first by proving that the r from step 2. can always be found and second by proving the above two claims. Furthermore, the paper[1] concerned itself with establishing its asymptotic time complexity.

[edit] Running time

Since the running times of step 2. and step 5. are entirely dependent on the magnitude of r, proving an upper bound on r was sufficient to show that the asymptotic time complexity of the algorithm is O(log12 + ε(n)), where ε is a small number. In other words, the algorithm takes less time than a constant times the twelfth (plus ε) power of the number of digits in n.

However the upper bound proven in the paper is quite loose; indeed, a widely held conjecture about the distribution of the Sophie Germain primes would, if true, immediately cut the worst case down to O(log6 + ε(n)).

In the following months after the discovery new variants appeared (Lenstra 2002, Pomerance 2002, Berrizbeitia 2003, Cheng 2003, Bernstein 2003a/b, Lenstra and Pomerance 2003) which improved AKS' speed by orders of magnitude. Due to the existence of the many variants, Crandall and Papadopoulos refer to the "AKS-class" of algorithms in their scientific paper "On the implementation of AKS-class primality tests" published in March 2003.

[edit] AKS Updated

In response to some of these variants and other feedback the paper "PRIMES is in P" was republished with a new formulation of the AKS algorithm and its proof of correctness. While the basic idea remained the same, r was chosen in a new manner and the proof of correctness was more coherently organized. While the previous proof relied on many different methods the new version relied almost exclusively on the behavior of cyclotomic polynomials over finite fields.

Again the AKS algorithm consists of two parts, and the first step is to find a suitable r; however, in the new version r is the smallest number such that or(n) > log2(n).

In the second step the equivalence

is again tested, this time for all positive integers less than  log(n).

log(n).

These changes improved the flow of the proof of correctness. It also allowed for an improved bound on the time complexity which is now O(log10.5(n)).

Hendrik Lenstra and Carl Pomerance show how to choose polynomials in the test such that a time bound of Õ(log6(n)) is achieved [2].

[edit] References

- ^ a b c d Manindra Agrawal, Neeraj Kayal, Nitin Saxena, "PRIMES is in P", Annals of Mathematics 160 (2004), no. 2, pp. 781–793.

- ^ a b H. W. Lenstra, Jr. and Carl Pomerance, "Primality Testing with Gaussian Periods", preliminary version July 20, 2005.

[edit] External links

- Eric W. Weisstein, AKS Primality Test at MathWorld.

- R. Crandall, Apple ACG, and J. Papadopoulos (March 18, 2003): On the implementation of AKS-class primality tests (PDF)

- Article by Borneman, containing photos and information about the three Indian scientists (PDF)

- Andrew Granville: It is easy to determine whether a given integer is prime

- The Prime Facts: From Euclid to AKS, by Scott Aaronson (PDF)

- The PRIMES is in P little FAQ by Anton Stiglic

- 2006 Gödel Prize Citation

- 2006 Fulkerson Prize Citation

- The AKS "PRIMES in P" Algorithm Resource

|

|||||||||||||||||