Hypnosis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- For the states induced by hypnotic drugs, see Sleep or Unconsciousness.

- Hypnotized redirects here. For the Shanadoo song, see Hypnotized (song). For the Plies song, see Hypnotized (Plies song).

Hypnosis is a mental state (state theory) or set of attitudes (nonstate theory) usually induced by a procedure known as a hypnotic induction, which is commonly composed of a series of preliminary instructions and suggestions. Hypnotic suggestions may be delivered by a hypnotist in the presence of the subject ("hetero-suggestion"), or may be self-administered ("self-suggestion" or "autosuggestion"). The use of hypnotism for therapeutic purposes is referred to as "hypnotherapy".

The words 'hypnosis' and 'hypnotism' both derive from the term "neuro-hypnotism" (nervous sleep) coined by the Scottish physician and surgeon James Braid around 1841 to distinguish his theory and practice from those developed by Franz Anton Mesmer and his followers ("Mesmerism" or "animal magnetism").

Although a popular misconception is that hypnosis is a form of unconsciousness resembling sleep, contemporary research suggests that it is actually a wakeful state of focused attention[1] and heightened suggestibility,[2] with diminished peripheral awareness.[3] In the first book on the subject, Neurypnology (1843), Braid described "hypnotism" as a state of physical relaxation ("nervous sleep") accompanied and induced by mental concentration ("abstraction").[4]

Contents |

[edit] Characteristics

Skeptics point out the difficulty distinguishing between hypnosis and the placebo effect, proposing that the state called hypnosis is

[...] so heavily reliant upon the effects of suggestion and belief that it would be hard to imagine how a credible placebo control could ever be devised for a hypnotism study.[5]"

However, hypnotism itself originated out of very early placebo controlled experiments, conducted by Braid and others. Many researchers and clinicians would therefore object that hypnotic suggestion is explicitly intended to make use of the placebo effect, e.g., Irving Kirsch has proposed a definition of hypnosis as a "non-deceptive mega-placebo", i.e., a method which openly makes use of suggestion and employs methods to amplify its effects. It is therefore surprisingly difficult to distinguish between the views of skeptics and proponents regarding hypnotism.

[edit] Definitions

The earliest definition of hypnosis was given by Braid, who coined the term "hypnotism" as an abbreviation for "neuro-hypnotism", or nervous sleep, which he opposed to normal sleep, and defined as:

a peculiar condition of the nervous system, induced by a fixed and abstracted attention of the mental and visual eye, on one object, not of an exciting nature.[6]

Braid elaborated upon this brief definition in a later work,

[...] the real origin and essence of the hypnotic condition, is the induction of a habit of abstraction or mental concentration, in which, as in reverie or spontaneous abstraction, the powers of the mind are so much engrossed with a single idea or train of thought, as, for the nonce, to render the individual unconscious of, or indifferently conscious to, all other ideas, impressions, or trains of thought. The hypnotic sleep, therefore, is the very antithesis or opposite mental and physical condition to that which precedes and accompanies common sleep [...] [7]

Braid therefore defined hypnotism as a state of mental concentration which often led to a form of progressive relaxation termed "nervous sleep". Later, in his The Physiology of Fascination (1855), Braid conceded that his original terminology was misleading, and argued that the term "hypnotism" or "nervous sleep" should be reserved for the minority (10%) of subjects who exhibited amnesia, substituting the term "monoideism", meaning concentration upon a single idea, as a description for the more alert state experienced by the others.

A contemporary account of hypnosis, derived from academic psychology, was provided in 2005, when the Society for Psychological Hypnosis, Division 30 of the American Psychological Association (APA), published the following formal definition,

The American Psychological Association's Definition of Hypnosis

Hypnosis typically involves an introduction to the procedure during which the subject is told that suggestions for imaginative experiences will be presented. The hypnotic induction is an extended initial suggestion for using one's imagination, and may contain further elaborations of the introduction. A hypnotic procedure is used to encourage and evaluate responses to suggestions. When using hypnosis, one person (the subject) is guided by another (the hypnotist) to respond to suggestions for changes in subjective experience, alterations in perception, sensation, emotion, thought or behaviour. Persons can also learn self-hypnosis, which is the act of administering hypnotic procedures on one's own. If the subject responds to hypnotic suggestions, it is generally inferred that hypnosis has been induced. Many believe that hypnotic responses and experiences are characteristic of a hypnotic state. While some think that it is not necessary to use the word "hypnosis" as part of the hypnotic induction, others view it as essential.

Details of hypnotic procedures and suggestions will differ depending on the goals of the practitioner and the purposes of the clinical or research endeavor. Procedures traditionally involve suggestions to relax, though relaxation is not necessary for hypnosis and a wide variety of suggestions can be used including those to become more alert. Suggestions that permit the extent of hypnosis to be assessed by comparing responses to standardised scales can be used in both clinical and research settings. While the majority of individuals are responsive to at least some suggestions, scores on standardised scales range from high to negligible.[8]

[edit] Induction

Hypnosis is normally preceded by a "hypnotic induction" technique. Traditionally this was interpreted as a method of putting the subject into a "hypnotic trance"; however subsequent "nonstate" theorists have viewed it differently, as a means of heightening client expectation, defining their role, focusing attention, etc. There are an enormous variety of different induction techniques used in hypnotism. However, by far the most influential method was the original "eye-fixation" technique of Braid, also known as "Braidism". Many variations of the eye-fixation approach exist, including the induction used in the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (SHSS), the most widely-used research tool in the field of hypnotism. Braid's original description of his induction is as follows,

James Braid's Original Eye-Fixation Hypnotic Induction Method

Take any bright object (I generally use my lancet case) between the thumb and fore and middle fingers of the left hand; hold it from about eight to fifteen inches from the eyes, at such position above the forehead as may be necessary to produce the greatest possible strain upon the eyes and eyelids, and enable the patient to maintain a steady fixed stare at the object.

The patient must be made to understand that he is to keep the eyes steadily fixed on the object, and the mind riveted on the idea of that one object. It will be observed, that owing to the consensual adjustment of the eyes, the pupils will be at first contracted: they will shortly begin to dilate, and after they have done so to a considerable extent, and have assumed a wavy motion, if the fore and middle fingers of the right hand, extended and a little separated, are carried from the object towards the eyes, most probably the eyelids will close involuntarily, with a vibratory motion. If this is not the case, or the patient allows the eyeballs to move, desire him to begin anew, giving him to understand that he is to allow the eyelids to close when the fingers are again carried towards the eyes, but that the eyeballs must be kept fixed, in the same position, and the mind riveted to the one idea of the object held above the eyes. It will generally be found, that the eyelids close with a vibratory motion, or become spasmodically closed.[9]

Braid himself later acknowledged that the hypnotic induction technique was not necessary in every case and subsequent researchers have generally found that on average it contributes less than previously expected to the effect of hypnotic suggestions (q.v., Barber, Spanos & Chaves, 1974). Many variations and alternatives to the original hypnotic induction techniques were subsequently developed. However, exactly 100 years after Braid introduced the method, another expert could still state: "It can be safely stated that nine out of ten hypnotic techniques call for reclining posture, muscular relaxation, and optical fixation followed by eye closure."[10]

[edit] Suggestion

When Braid first introduced hypnotism, he did not use the term "suggestion" but referred instead to the act of focusing the conscious mind of the subject upon a single dominant idea. Braid's main therapeutic strategy involved stimulating or reducing physiological functioning in different regions of the body. In his later works, however, Braid placed increasing emphasis upon the use of a variety of different verbal and non-verbal forms of suggestion, including the use of "waking suggestion" and self-hypnosis. Subsequently, Hippolyte Bernheim shifted the emphasis from the physical state of hypnosis on to the psychological process of verbal suggestion.

I define hypnotism as the induction of a peculiar psychical [i.e., mental] condition which increases the susceptibility to suggestion. Often, it is true, the [hypnotic] sleep that may be induced facilitates suggestion, but it is not the necessary preliminary. It is suggestion that rules hypnotism. (Hypnosis & Suggestion, 1884: 15)

Bernheim's conception of the primacy of verbal suggestion in hypnotism dominated the subject throughout the twentieth century, leading some authorities to declare him the father of modern hypnotism (Weitzenhoffer, 2000). Contemporary hypnotism makes use of a wide variety of different forms of suggestion including: direct verbal suggestions, "indirect" verbal suggestions such as requests or insinuations, metaphors and other rhetorical figures of speech, and non-verbal suggestion in the form of mental imagery, voice tonality, and physical manipulation. A distinction is commonly made between suggestions delivered "permissively" or in a more "authoritarian" manner. Some hypnotic suggestions are intended to bring about immediate responses, whereas others (post-hypnotic suggestions) are intended to trigger responses after a delay ranging from a few minutes to many years in some reported cases.

[edit] Consciousness vs. unconscious mind

Some hypnotists conceive of suggestions as being a form of communication directed primarily to the subject's conscious mind, whereas others view suggestion as a means of communicating with the "unconscious" or "subconscious" mind. These concepts were introduced into hypnotism at the end of 19th century by Sigmund Freud and Pierre Janet. The original Victorian pioneers of hypnotism, including Braid and Bernheim, did not employ these concepts but considered hypnotic suggestions to be addressed to the subject's conscious mind. Indeed, Braid actually defines hypnotism as focused (conscious) attention upon a dominant idea (or suggestion). Different views regarding the nature of the mind have led to different conceptions of suggestion. Hypnotists who believed that responses are mediated primarily by an "unconscious mind", like Milton Erickson, made more use of indirect suggestions, such as metaphors or stories, whose intended meaning may be concealed from the subject's conscious mind. The concept of subliminal suggestion also depends upon this view of the mind. By contrast, hypnotists who believed that responses to suggestion are primarily mediated by the conscious mind, such as Theodore Barber and Nicholas Spanos tended to make more use of direct verbal suggestions and instructions.

[edit] Ideo-dynamic reflex

The first neuro-psychological theory of hypnotic suggestion was introduced early on by James Braid who adopted his friend and colleague William Carpenter's theory of the ideo-motor reflex response to account for the phenomena of hypnotism. Carpenter had observed from close examination of everyday experience that under certain circumstances the mere idea of a muscular movement could be sufficient to produce a reflexive, or automatic, contraction or movement of the muscles involved, albeit in a very small degree. Braid extended Carpenter's theory to encompass the observation that a wide variety of bodily responses, other than muscular movement, can be thus affected, e.g., the idea of sucking a lemon can automatically stimulate salivation, a secretory response. Braid therefore adopted the term "ideo-dynamic", meaning "by the power of an idea" to explain a broad range of "psycho-physiological" (mind-body) phenomena. Braid coined the term "mono-ideodynamic" to refer to the theory that hypnotism operates by concentrating attention on a single idea in order to amplify the ideo-dynamic reflex response. Variations of the basic ideo-motor or ideo-dynamic theory of suggestion have continued to hold considerable influence over subsequent theories of hypnosis, including those of Clark L. Hull, Hans Eysenck, and Ernest Rossi. It should be noted that in Victorian psychology, the word "idea" encompasses any mental representation, e.g., including mental imagery, or memories, etc.

[edit] Post-hypnotic suggestion

Post-hypnotic suggestion can be used to change people's behaviour after emerging from hypnosis. One author wrote that "a person can act, some time later, on a suggestion seeded during the hypnotic session... A hypnotherapist told one of his patients, who was also a friend: 'When I touch you on the finger you will immediately be hypnotised.' Fourteen years later, at a dinner party, he touched him deliberately on the finger and his head fell back against the chair."[11]

[edit] Susceptibility

Braid made a rough distinction between different stages of hypnosis which he termed the first and second conscious stage of hypnotism, he later replaced this with a distinction between "sub-hypnotic", "full hypnotic", and "hypnotic coma" stages. Jean-Martin Charcot made a similar distinction between stages named somnambulism, lethargy, and catalepsy. However, Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault and Bernheim introduced more complex hypnotic "depth" scales, based on a combination of behavioural, physiological and subjective responses, some of which were due to direct suggestion and some of which were not. In the first few decades of the 20th century, these early clinical "depth" scales were superseded by more sophisticated "hypnotic susceptibility" scales based on experimental research. The most influential were the Davis-Husband and Friedlander-Sarbin scales developed in the 1930s. Andre Weitzenhoffer and Ernest R. Hilgard developed the Stanford Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility in 1959, consisting of 12 suggestion test items following a standardised hypnotic eye-fixation induction script, and this has become one of the most widely-referenced research tools in the field of hypnosis. Soon after, in 1962, Ronald Shor and Emily Carota Orne developed a similar group scale called the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility (HGSHS).

Whereas the older "depth scales" tried to infer the level of "hypnotic trance" based upon supposed observable signs, such as spontaneous amnesia, most subsequent scales measure the degree of observed or self-evaluated responsiveness to specific suggestion tests, such as direct suggestions of arm rigidity (catalepsy).

[edit] History

[edit] Precursors

According to his writings, Braid began to hear reports concerning the practices of various Oriental meditation techniques immediately after the publication of his major book on hypnotism, Neurypnology (1843). Braid first discusses hypnotism's historical precursors in a series of articles entitled Magic, Mesmerism, Hypnotism, etc., Historically & Physiologically Considered. He draws analogies between his own practice of hypnotism and various forms of Hindu yoga meditation and other ancient spiritual practices. Braid’s interest in meditation really developed when he was introduced to the Dabistān-i Mazāhib, the “School of Religions”, an ancient Persian text describing a wide variety of Oriental religious practices.

Last May [1843], a gentleman residing in Edinburgh, personally unknown to me, who had long resided in India, favored me with a letter expressing his approbation of the views which I had published on the nature and causes of hypnotic and mesmeric phenomena. In corroboration of my views, he referred to what he had previously witnessed in oriental regions, and recommended me to look into the “Dabistan,” a book lately published, for additional proof to the same effect. On much recommendation I immediately sent for a copy of the “Dabistan”, in which I found many statements corroborative of the fact, that the eastern saints are all self-hypnotisers, adopting means essentially the same as those which I had recommended for similar purposes.[13]

Although he disputed the religious interpretation given to these phenomena throughout this article and elsewhere in his writings, Braid seized upon these accounts of Oriental meditation as proof that the effects of hypnotism could be produced in solitude, without the presence of a magnetiser, and therefore saw this as evidence that the real precursor of hypnotism was to be sought in the ancient practices of meditation rather than in the more recent theory and practice of Mesmerism. As he later wrote,

Inasmuch as patients can throw themselves into the nervous sleep, and manifest all the usual phenomena of Mesmerism, through their own unaided efforts, as I have so repeatedly proved by causing them to maintain a steady fixed gaze at any point, concentrating their whole mental energies on the idea of the object looked at; or that the same may arise by the patient looking at the point of his own finger, or as the Magi of Persia and Yogi of India have practised for the last 2,400 years, for religious purposes, throwing themselves into their ecstatic trances by each maintaining a steady fixed gaze at the tip of his own nose; it is obvious that there is no need for an exoteric influence to produce the phenomena of Mesmerism. […] The great object in all these processes is to induce a habit of abstraction or concentration of attention, in which the subject is entirely absorbed with one idea, or train of ideas, whilst he is unconscious of, or indifferently conscious to, every other object, purpose, or action. [14]

[edit] Franz Mesmer

Franz Mesmer (1734-1815) believed that there was a magnetic force or "fluid" within the universe which influenced the health of the human body. He experimented with magnets to influence this field and so cause healing. By around 1774 he had concluded that the same effects could be created by passing the hands, at a distance, in front of the subject's body, referred to as making "Mesmeric passes." The word mesmerise originates from the name of Franz Mesmer; and was intentionally used to separate its users from the various "fluid" and "magnetic" theories embedded within the label "magnetist".

In 1784, at the request of King Louis XVI, Mesmer's theories were scrutinised by a series of French scientific committees, one of which included the American ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin. They also investigated the practices of a disaffected student of Mesmer, one Charles d'Eslon (1750-1786), and on the basis of their examination of d'Eslon's manner of working (not Mesmer's), and despite the fact that they accepted that the results that were claimed by Mesmer were in fact veridical, their placebo controlled experiments of d'Eslon's practices clearly demonstrate that the effects of Mesmerism were most likely due to belief and imagination rather than to any sort of invisible energy ("animal magnetism") being transmitted from the body of the Mesmerist.

In other words, despite accepting that Mesmer's practice seemed to have a certain efficacy, both committees totally rejected all of Mesmer's theories.

[edit] James Braid

Following the French committee's findings, in his Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind (1827), Dugald Stewart, an influential academic philosopher of the "Scottish School of Common Sense", encouraged physicians to salvage elements of Mesmerism by replacing the supernatural theory of "animal magnetism" with a new interpretation based upon "common sense" laws of physiology and psychology. Braid explicitly quotes the following passage from Stewart[15],

It appears to me, that the general conclusions established by Mesmer’s practice, with respect to the physical effects of the principle of imagination [...] are incomparably more curious than if he had actually demonstrated the existence of his boasted science [of "animal magnetism"]: nor can I see any good reason why a physician, who admits the efficacy of the moral [i.e., psychological] agents employed by Mesmer, should, in the exercise of his profession, scruple to copy whatever processes are necessary for subjecting them to his command, any more than that he should hesitate about employing a new physical agent, such as electricity or galvanism.[16]

In Braid's day, the Scottish School of Common Sense provided the dominant theories of academic psychology and Braid frequently refers to other philosophers within this tradition throughout his writings. Braid therefore revised the theory and practice of Mesmerism and developed his own method of "hypnotism" as a more rational and "common sense" alternative.

It may here be requisite for me to explain, that by the term Hypnotism, or Nervous Sleep, which frequently occurs in the following pages, I mean a peculiar condition of the nervous system, into which it may be thrown by artificial contrivance, and which differs, in several respects, from common sleep or the waking condition. I do not allege that this condition is induced through the transmission of a magnetic or occult influence from my body into that of my patients; nor do I profess, by my processes, to produce the higher [i.e., supernatural] phenomena of the Mesmerists. My pretensions are of a much more humble character, and are all consistent with generally admitted principles in physiological and psychological science. Hypnotism might therefore not inaptly be designated, Rational Mesmerism, in contra-distinction to the Transcendental Mesmerism of the Mesmerists.[17]

Despite briefly toying with the name "rational Mesmerism", Braid ultimately distanced his approach from Mesmer's and emphasised its uniqueness, carrying out many informal experiments throughout his career to refute the theories of Mesmerists and other supernatural practices, and demonstrate instead the role of ordinary physiological and psychological processes such as suggestion and focused attention in producing the effects observed.

Braid worked very closely with his friend and ally the eminent physiologist Professor William Benjamin Carpenter an early neuro-psychologist, who introduced the "ideo-motor reflex" theory of suggestion. Carpenter had observed many everyday examples of expectation and imagination apparently influencing the movement of muscles involuntarily.[18]

Braid soon assimilated Carpenter's observations into his own theory of hypnotism, realising that the effect of focusing attention was to enhance the ideo-motor reflex response. Braid extended Carpenter's theory to encompass the influence of the mind upon the body more generally, beyond the muscular system, and therefore referred to the "ideo-dynamic" response and coined the term "psycho-physiology" to refer to the study of interaction between the mind and body in general.

In his later works, Braid reserved the term "hypnotism" for the small minority of cases in which subjects entered a state of amnesia resembling sleep. For the rest, he spoke of "mono-ideodynamic" principle of action to emphasise that the eye-fixation induction technique worked by narrowing the focus of their attention to a single idea or train of thought ("monoideism") which thereby amplified the effect of the consequent "dominant idea" upon the subject's body by means of the ideo-dynamic principle.

[edit] Hysteria vs. suggestion

For several decades, Braid's work became more influential abroad than in his own country, except for a handful of followers, most notably Dr. John Milne Bramwell. The eminent neurologist Dr. George Miller Beard took Braid's theories to America. Meanwhile his works were translated into German by Wilhelm T. Preyer, Professor of Physiology at Jena University. The psychiatrist Albert Moll subsequently continued German research, publishing his Hypnotism in 1889. However, the study of hypnotism mainly became focused in France, after Braid's research was presented before the French Academy of Sciences by the eminent neurologist Dr. Étienne Eugène Azam who also translated Braid's last manuscript (On Hypnotism, 1860) into French. The French Academy of Science, who had previously examined Mesmerism in 1784, therefore subsequently examined the writings of Braid, shortly after his demise, at the request of Azam, Paul Broca, and others.

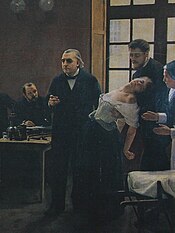

Azam's enthusiasm for hypnotism influenced Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault, a country doctor whose enormously popular group hypnotherapy clinic was discovered by Hippolyte Bernheim who subsequently became himself an influential hypnotist. The study of hypnotism subsequently became centred upon a fierce rivalry and debate between Jean-Martin Charcot and Hippolyte Bernheim, the two most influential figures in late 19th century hypnotism.

An important argument developed between Charcot's "Hysteria School", centered on Charcot's clinic at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital (thus, also known as the "Paris School" or the "Salpêtrière School") and Bernheim's "Suggestion School", centred on Bernheim's Nancy clinic (thus, also known as the "Nancy School" over the true nature of hypnosis. Charcot, influenced more by the Mesmerists, argued that hypnotism was an abnormal state of nervous functioning found only in certain hysterical women. He claimed that it was manifested in the form of a series of physical reactions which could be divided into distinct stages. Bernheim argued against Charcot that anyone could be hypnotised, that it was an extension of normal psychological functioning, and that its effects were variable being primarily due to suggestion. After several decades of debate, Bernheim's view eventually came to dominate and Charcot's theory of hypnosis is now seen as little more than a historical curiosity.

[edit] Pierre Janet

Pierre Janet (1859-1947) reported some initial studies on a hypnotic subject in 1882 which came to the attention of Charcot who subsequently appointed him director of the psychological laboratory at the Salpêtrière in 1889, after Janet completed his PhD in philosophy which dealt with the subject of psychological automatism. In 1898 Janet was appointed lecturer in psychology at the Sorbonne, and in 1902 he became chair of experimental and comparative psychology at the Collège de France. Janet reconciled elements of his views with those of Bernheim and his followers, developing his own sophisticated hypnotic psychotherapy based upon the concept of psychological dissociation which, at the turn of the century, rivalled Freud's attempt to provide a more comprehensive psychological theory of psychotherapy.

[edit] Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, subsequently studied hypnotism at Charcot's Paris school and briefly visited Bernheim's Nancy school.

Initially, Freud was an enthusiastic proponent of hypnotherapy, and soon began to emphasise and popularise the use of hypnotic regression and ab reaction (catharsis) as therapeutic methods. He wrote a favorable encyclopedia article on hypnotism, translated one of Bernheim's works into German, and published an influential series of case studies with his colleague Joseph Breuer entitled Studies on Hysteria (1895). This became the founding text of the subsequent tradition known as "hypno-analysis" or "regression hypnotherapy."

However, Freud gradually abandoned the use of hypnotism in favour of his developing methods of psychoanalysis, through free association and interpretation of the unconscious. Struggling with the great expense of time required for psychoanalysis to be successful, Freud later suggested that it might be combined with hypnotic suggestion once more in an attempt to hasten the outcome of treatment,

It is very probable, too, that the application of our therapy to numbers will compel us to alloy the pure gold of analysis plentifully with the copper of direct [hypnotic] suggestion. [19]

However, only a handful of Freud's followers were sufficiently qualified in hypnosis to attempt the synthesis. Their work had a limited influence on the gradual emergence of the hypno-therapeutic approaches now known variously as "hypnotic regression", "hypnotic progression", and "hypnoanalysis".

[edit] Émile Coué

Émile Coué (1857-1926) served for around two years as an assistant to Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault in his group hypnotic at Nancy. However, after practicing for several years as a hypnotherapist employing the methods of Liébeault and Bernheim's Nancy School, Coué gradually began to develop a new orientation called "conscious autosuggestion." Several years after Liébeault's death in 1904, Coué founded what became known as the New Nancy School, a loose collaboration of practitioners who taught and promoted his views. Coué's method did not emphasise "sleep" or deep relaxation and instead focused upon teaching groups of clients how to use autosuggestion by trial and error learning involving a specific series of suggestion tests. Although Coué argued that he was no longer using hypnosis, some of his followers, such as Charles Baudouin, viewed his approach as a form of light self-hypnosis. Coué's method became an internationally renowned self-help and psychotherapy technique, which contrasted with the methods of Freud's method of psychoanalysis and prefigured subsequent self-hypnosis techniques and, in some regards, the development of cognitive therapy.

[edit] Clark L. Hull

The next major event in the history of hypnotism came as a result of the progress of behavioural psychology in American university research. Clark L. Hull, an eminent American psychologist, published the first major compilation of laboratory studies on hypnosis, Hypnosis & Suggestibility (1933), in which he conclusively proved that the state of hypnosis and the state of sleep had nothing in common. Hull published many quantitative empirical findings derived from experiments using hypnosis and suggestion and thereby encouraged subsequent research into hypnosis by mainstream academic psychologists. Hull's behavioural psychology interpretation of hypnosis, in terms of conditioned reflexes, rivaled the Freudian psycho dynamic interpretation in terms of unconscious transference.

[edit] Milton Erickson

Milton H. Erickson, M.D. was one of the most influential post-war hypnotherapists. He wrote several books and journal articles on the subject. During the 1960s, Erickson was responsible for popularizing a new branch of hypnotherapy, which became known as Ericksonian hypnotherapy, eventually characterised by, amongst other things, the absence of a formal hypnotic inductions, and the use of indirect suggestion, "metaphor" (actually they were analogies, rather than "metaphors"), confusion techniques, and double binds. However, the lack of resemblance between Erickson's methods and those of traditional hypnotism led some of his contemporaries, such as André Weitzenhoffer, to seriously question whether he was actually practicing "hypnosis" at all, and the status of his approach in relation to traditional hypnotism has remained in question.

Erickson had no hesitation in presenting any suggested effect as being "hypnosis", whether or not the subject was in a hypnotic state. In fact, he was not hesitant in passing off behaviour that was dubiously hypnotic as being hypnotic. [20]

[edit] Cognitive-behavioural

In the latter half of the twentieth century, two factors contributed to the development of what subsequently became known as the cognitive-behavioural approach to hypnosis. 1) Cognitive and behavioural theories of the nature of hypnosis (influenced by the seminal theories of Sarbin[21] and Barber [22]) became increasingly influential. 2) The therapeutic practices of hypnotherapy and various forms of cognitive-behavioural therapy overlapped and influenced each other.[23] Although cognitive-behavioural theories of hypnosis must be distinguished from cognitive-behavioural approaches to hypnotherapy, they share similar concepts, terminology, and assumptions and have been integrated by influential researchers and clinicians such as Irving Kirsch, Steven Jay Lynn, and others [24].

Hypnosis was used during the 1950s, at the outset of cognitive-behavioural therapy, by early behaviour therapists such as Joseph Wolpe[25] and also by early cognitive therapists such as Albert Ellis[26]. The term "cognitive-behavioural" was subsequently introduced to describe their "nonstate" theory of hypnosis by Barber, Spanos & Chaves in Hypnotism: Imagination & Human Potentialities (1974)[27]. However, Clark L. Hull had introduced an influential behavioural psychology approach to the study of hypnosis as far back as 1933, which was preceded by Ivan Pavlov's own writings on the subject[28]. Indeed, the very earliest theories and practices of hypnotism, even those of Braid, resemble the cognitive-behavioural orientation in some respects[29].

[edit] Uses

[edit] Hypnotherapy

Modern hypnotherapy can be divided into several major sub-modalities, most notably regression hypnotherapy (or "hypnoanalysis"), Ericksonian hypnotherapy, and cognitive-behavioural hypnotherapy.

Hypnosis has been studied in many clinical situations with varying degrees of success.[30] It has been used as a painkiller,[31] an adjunct to weight loss,[32] a treatment of skin disease,[33] and a way to soothe anxious surgical patients. It has also been used as part of psychological therapy,[34] a method of habit control,[35] a way to relax,[36] and a tool to enhance sports performance.[37]

Self-hypnosis is popularly used by people who want to quit smoking and reduce stress, while stage hypnosis can be used to persuade people to perform unusual public feats.[38]

[edit] Medical applications

Hypnotherapy has been successfully used as a treatment for irritable bowel syndrome, a pair of researchers who recently reviewed the best studies in this area, conclude,

The evidence for hypnosis as an efficacious treatment of IBS was encouraging. Two of three studies that investigated the use of hypnosis for IBS were well designed and showed a clear effect for the hypnotic treatment of IBS. [40]

Hypnosis for IBS has also received moderate support as an evidence-based treatment in the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidance published for the UK health services.[41] It has been used as an alternative to chemical anaesthesia,[42][43][44] and it has been studied as a way to soothe skin ailments.[45]

A large number of clinical studies show that hypnosis can reduce the pain experienced by people undergoing burn-wound debridement, bone marrow aspirations, and childbirth. The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis found that hypnosis relieved the pain of 75% of 933 subjects participating in 27 different experiments.[46]

In 1996, the National Institutes of Health declared hypnosis effective in reducing pain from cancer and other chronic conditions.[46] Nausea and other symptoms related to incurable diseases may also be controlled with hypnosis.[47][48][49][50] For example, research done at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine studied two groups of patients facing surgery for breast cancer. The group that received hypnosis reported less pain, nausea, and anxiety post-surgery. There was a cost benefit as well: the average hypnosis patient reduced the cost of treatment by an average of $772.00.[51][52]

Hypnodermatology is the practice of treating skin diseases with hypnosis: this therapy has performed well in studies treating warts, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis.[53]

Hypnosis may be useful as an adjunct therapy for weight loss. A 1996 meta-analysis studying the effectiveness of hypnosis combined with cognitive-behavioural therapy found that people using both treatments lost more weight than people using CBT alone.[54]

[edit] Psychotherapy

Hypnotherapy is the use of hypnosis in psychotherapy.[55] It is used by licensed physicians, psychologists, and in stand-alone environments. Physicians and psychiatrists may use hypnosis to help treat depression, anxiety, eating disorders, sleep disorders, compulsive gaming, and posttraumatic stress disorder.[56][57]

Certified hypnotherapists who are not physicians or psychologists often do treatments for smoking cessation and weight loss. (Success rates vary: a meta-study researching hypnosis as a quit-smoking tool found it had a 20 to 30 percent success rate, similar to many other quit-smoking methods,[58] while a 2007 study of patients hospitalised for cardiac and pulmonary ailments found that smokers who used hypnosis to quit smoking doubled their chances of success.[59])

In a July 2001 article for Scientific American titled "The Truth and the Hype of Hypnosis", Michael Nash wrote that "...using hypnosis, scientists have temporarily created hallucinations, compulsions, certain types of memory loss, false memories, and delusions in the laboratory so that these phenomena can be studied in a controlled environment."[46]

Controversy surrounds the use of hypnotherapy to retrieve memories, especially those from early childhood or (alleged) past-lives. The American Medical Association and the American Psychological Association have cautioned against the use of repressed memory therapy in cases of alleged childhood trauma, stating that "it is impossible, without other corroborative evidence, to distinguish a true memory from a false one."[60] Past life regression, meanwhile, is often viewed with skepticism.[61]

[edit] Self-hypnosis

Self-hypnosis happens when a person hypnotises himself or herself, commonly involving the use of autosuggestion. The technique is often used to increase motivation for a diet, quit smoking, or reduce stress. People who practice self-hypnosis sometimes require assistance; some people use devices known as mind machines to assist in the process, while others use hypnotic recordings.

Self-hypnosis is said to be a skill one can improve as time goes by, and can help reduce stage fright, promote relaxation, and enhance physical well-being.[62]

[edit] Stage hypnosis

Stage hypnosis is a form of entertainment, traditionally employed in a club or theatre before an audience. Due to stage hypnotists' showmanship, many people believe that hypnosis is a form of mind control. However, the effects of stage hypnosis are probably due to a combination of relatively ordinary social psychological factors such as peer pressure, social compliance, participant selection, ordinary suggestibility, and some amount of physical manipulation, stagecraft, and trickery.[63] The desire to be the centre of attention, having an excuse to violate their own inner fear suppressors and the pressure to please are thought to convince subjects to 'play along'.[64][page number needed] Books written by stage hypnotists sometimes explicitly describe the use of deception in their acts, for example, Ormond McGill's New Encyclopedia of Stage Hypnosis describes an entire "fake hypnosis" act which depends upon the use of private whispers throughout.

[The hypnotist whispers off-microphone:] “We are going to have some good laughs on the audience and fool them… so when I tell you to do some funny things, do exactly as I secretly tell you. Okay? Swell.” (Then deliberately wink at the spectator in a friendly fashion.) [65]

Stage hypnosis traditionally employs three fundamental strategies,

- Participant compliance. Participants on stage tend to be compliant because of the social pressure felt in the situation constructed on stage, before an expectant audience.

- Participant selection. Preliminary suggestion tests, such as asking the audience to clasp their hands and suggesting they cannot be separated, are usually used to select out the most suggestible and compliant subjects from the audience. By asking for volunteers to mount the stage, the performer also tends to select the most extroverted members of the audience.

- Deception of the audience. Stage hypnotists are performers who traditionally, but not always, employ a variety of "sleight of hand" strategies to mislead their audience for dramatic effect.

The strategies of deception employed in traditional stage hypnosis can be categorised as follows,

- Off-microphone whispers. The hypnotist lowers his microphone and whispers secret instructions to the participant on stage, outside of the audience's hearing. These may involve requests to "play along" or fake hypnotic responses.

- Failure to challenge. The stage hypnotist pretends to challenge subjects to defy a suggestion, e.g., "You cannot stand up out of your chair because your backside is stuck down with glue." However, no specific cue is given to the participants to begin their effort ("Start trying now!"). This creates the illusion that a specific challenge has been issued and effort made to defy it.

- Fake hypnosis tricks. Stage hypnosis literature contains a large repertoire of sleight of hand tricks, of the kind used by professional illusionists. None of these tricks require any hypnosis or suggestion, but depend purely on physical manipulation and audience deception. The most famous example of this type is the "human plank" trick, which involves making a subject's body become rigid (cataleptic) and suspending them horizontally between two chairs, at which point the hypnotist will often stand upon their chest for dramatic effect. This has nothing to do with hypnosis, but simply depends on the fact that when subjects are positioned in the correct way they can support more weight than the audience tend to assume.

[edit] Other uses

Hypnotism has also been used in forensics, sports, education, physical therapy and rehabilitation.[66] Hypnotism has also been employed by artists for creative purposes most notably the surrealist circle of André Breton who employed hypnosis and automatic writing and sketches for creative purposes.

Some people have drawn analogies between certain aspects of hypnotism and areas such as crowd psychology, religious hysteria, and ritual trances in preliterate tribal cultures.[67][page number needed]

[edit] Theories

[edit] The State versus Nonstate Debate

The central theoretical disagreement in the history of hypnotism is known as the "state versus nonstate" debate. When Braid introduced the concept of hypnotism he equivocated over the nature of the "state", sometimes describing it as a specific sleep-like neurological state comparable to animal hibernation or yogic meditation, while at other times he emphasised that hypnotism encompassed a number of different stages or states which were essentially an extension of ordinary psychological and physiological processes. Overall, Braid appears to have moved from a more "special state" understanding of hypnotism, at the start of his career, toward a more complex "nonstate" orientation in his later works.

State theorists traditionally interpreted the effects of hypnotism as primarily due to a specific, abnormal and uniform psychological or physiological state of some description, often referred to as "hypnotic trance" or an "altered state of consciousness." Nonstate theorists rejected the idea of hypnotic trance and interpret the effects of hypnotism as due to a combination of multiple task-specific factors derived from normal cognitive, behavioural and social psychology, such as social role-perception and favorable motivation (Sarbin ), active imagination and positive cognitive set (Barber), response expectancy (Kirsch), and the active use of task-specific subjective strategies (Spanos). The personality psychologist Robert White is often cited as providing one of the first nonstate definitions of hypnosis in a 1941 article:

Hypnotic behaviour is meaningful, goal-directed striving, its most general goal being to behave like a hypnotised person as this is continuously defined by the operator and understood by the client. [68]

Put simply, it is often stated that whereas the older "special state" interpretation emphasises the difference between hypnosis and ordinary psychological processes, the "nonstate" interpretation emphasises the similarity, continuity, or overlap. In practical terms, nonstate theorists tend to see more of an overlap between hypnotherapy and other forms of psychological therapy, insofar as they employ mental imagery, verbal suggestion, etc., whereas state theorists tend to see hypnotherapy as operating by means of an altered state of consciousness not emphasised in most other psychological therapies.

Comparisons between hypnotised and non-hypnotised subjects suggest that if "hypnotic trance" does exist it probably only accounts for a very small proportion of the effects normally attributed to hypnotic suggestion, most of which can be replicated without the use of a hypnotic induction technique.

[edit] Hyper-suggestibility

Braid can be taken to imply, in some of his later writings, that hypnosis is largely a state of heightened suggestibility induced by habit, expectation, and focused attention. In particular, Hippolyte Bernheim became known as the leading proponent of the "suggestion theory" of hypnosis, at one point going so far as to declare that there is no hypnosis (as a specific state) only heightened suggestibility. There is a general consensus among most researchers and clinicians that heightened suggestibility is an essential characteristic of hypnosis, although disagreement exists as to whether this depends upon the induction of an altered state of consciousness ("hypnotic trance") or ordinary psychological and physiological factors which mediate the effect of suggestion (nonstate theory).

If a subject after submitting to the hypnotic procedure shows no genuine increase in susceptibility to any suggestions whatever, there seems no point in calling him hypnotised, regardless of how fully and readily he may respond to suggestions of lid-closure and other superficial sleeping behaviour.[69])

[edit] Conditioned Inhibition

Ivan Pavlov stated that hypnotic suggestion provided the best example of a conditioned reflex response in human beings, i.e., that responses to suggestions were learned associations triggered by the words used. Pavlov himself wrote,

Speech, on account of the whole preceding life of the adult, is connected up with all the internal and external stimuli which can reach the cortex, signaling all of them and replacing all of them, and therefore it can call forth all those reactions of the organism which are normally determined by the actual stimuli themselves. We can, therefore, regard ‘suggestion’ as the most simple form of a typical reflex in man.[70]

He also believed that hypnosis was a "partial sleep" by which he meant that by suggestions of sleep a generalised inhibition of cortical functioning could be encouraged to spread throughout certain regions of the brain. He observed that the various degrees of hypnosis did not significantly differ physiologically from the waking state and hypnosis depended on insignificant changes of environmental stimuli. Pavlov also suggested that lower-brain-stem mechanisms were involved in hypnotic conditioning.[71][page number needed][72]

Pavlov's ideas were combined with those of his rival Bekhterev and became the basis of hypnotic psychotherapy in the Soviet Union, as documented in the writings of his follower K.I. Platonov. Soviet theories of hypnotism subsequently influenced the writings of Western behaviourally-oriented hypnotherapists such as Andrew Salter. However, this theory of hypnosis as a specific state of conditioned cortical inhibition has received little subsequent support from researchers in the field of hypnosis.

[edit] Neuropsychology

Neurological imaging techniques have essentially failed to provide any evidence of a neurological pattern that can be directly equated with "hypnotic trance", however differences in brain activity have been found in some studies on highly-responsive hypnotic subjects. Moreover, these changes tend to be task-specific and vary depending upon the type of suggestions being given at the time. A recent review by leading experts who examined the laboratory research in this area concludes,

Hypnosis is not a unitary state and therefore should show different patterns of EEG activity depending upon the task being experienced. In our evaluation of the literature, enhanced theta is observed during hypnosis when there is task performance or concentrative hypnosis, but not when the highly hypnotizable individuals are passively relaxed, somewhat sleepy and/or more diffuse in their attention.[73]

Anna Gosline says in a NewScientist.com article:

- "Gruzelier and his colleagues studied brain activity using an fMRI while subjects completed a standard cognitive exercise, called the Stroop task.

- The team screened subjects before the study and chose 12 that were highly susceptible to hypnosis and 12 with low susceptibility. They all completed the task in the fMRI under normal conditions and then again under hypnosis.

- Throughout the study, both groups were consistent in their task results, achieving similar scores regardless of their mental state. During their first task session, before hypnosis, there were no significant differences in brain activity between the groups.

- But under hypnosis, Gruzelier found that the highly susceptible subjects showed significantly more brain activity in the anterior cingulate gyrus than the weakly susceptible subjects. This area of the brain has been shown to respond to errors and evaluate emotional outcomes.

- The highly susceptible group also showed much greater brain activity on the left side of the prefrontal cortex than the weakly susceptible group. This is an area involved with higher level cognitive processing and behaviour."[74]

[edit] Dissociation

Pierre Janet originally developed the idea of dissociation of consciousness as a result of his work with hysterical patients. He believed that hypnosis was an example of dissociation, whereby areas of an individual's behavioural control are split off from ordinary awareness. Hypnosis would remove some control from the conscious mind, and the individual would respond with autonomic, reflexive behaviour. Weitzenhoffer describes hypnosis via this theory as "dissociation of awareness from the majority of sensory and even strictly neural events taking place."[75][page number needed]

[edit] Neodissociation

Ernest Hilgard, who developed the "neodissociation" theory of hypnotism, hypothesised that hypnosis causes the subjects to divide our consciousness voluntarily. One part responds to the hypnotist while the other retains awareness of reality. When performing experiments, Hilgard made the subjects go into an ice water bath. They did not say anything about the water being cold or feeling pain. Hilgard then asked the subjects to lift their index finger if they felt pain and 70% of the subjects lifted their index finger. This showed that even though the subjects were listening to the suggestive hypnotist they still had some sense of consciousness.[76]

[edit] Social Role-Taking Theory

The main theorist who pioneered the influential role-taking theory of hypnotism was Theodore Sarbin. Sarbin argued that hypnotic responses were motivated attempts to fulfill the socially-constructed role of hypnotic subject. This has led to the misconception that hypnotic subjects are simply "faking". However, Sarbin was careful to emphasise that was not what he meant by distinguishing between role-playing, in which there is little subjective identification with the role in question, and role-taking, in which the subject not only acts externally in accord with the role but also subjectively identifies with it to some degree, acting, thinking, and feeling "as if" they are hypnotised. Sarbin drew analogies between role-taking in hypnosis and role-taking in other areas such as method acting, mental illness, and shamanic possession, etc. This interpretation of hypnosis is particularly relevant to understanding stage hypnosis in which there is clearly strong peer pressure to comply with a socially-constructed role by performing accordingly on a theatrical stage.

Hence, social constructionism and role-taking theory of hypnosis suggests that individuals are enacting (as opposed to merely playing) a role and that really there is no such thing as a hypnotic trance. A socially-constructed relationship is built depending on how much rapport has been established between the "hypnotist" and the subject (see Hawthorne effect, Pygmalion effect, and placebo effect).

Some psychologists, such as Robert Baker and Graham Wagstaff, claim that what we call hypnosis is actually a form of learned social behaviour, a complex hybrid of social compliance, relaxation, and suggestibility that can account for many esoteric behavioural manifestations.[77][page number needed]

[edit] Cognitive-behavioural theory

Barber, Spanos, & Chaves (1974) proposed a nonstate "cognitive-behavioural" theory of hypnosis, similar in some respects to Sarbin's social role-taking theory and building upon the earlier research of Barber. On this model, hypnosis is explained as an extension of ordinary psychological processes like imagination, relaxation, expectation, social compliance, etc. In particular, Barber argued that responses to hypnotic suggestions were mediated to a large extent by a "positive cognitive set" consisting of positive expectations, attitudes, and motivation. Daniel Araoz subsequently coined the acronym "TEAM" to symbolise the subject's orientation to hypnosis in terms of "trust", "expectation", "attitude", and "motivation".

Barber et al., noted that similar factors appeared to mediate the response both to hypnotism and to cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), in particular systematic desensitization. Hence, research and clinical practice inspired by their interpretation has led to growing interest in the relationship between hypnotherapy and CBT.

[edit] Information theory

An approach loosely based on Information theory uses a brain-as-computer model. In adaptive systems, a system may use feedback to increase the signal-to-noise ratio, which may converge towards a steady state. Increasing the signal-to-noise ratio enables messages to be more clearly received from a source. The hypnotist's object is to use techniques to reduce the interference and increase the receptability of specific messages (suggestions).[78]

[edit] Systems theory

Systems theory, in this context, may be regarded as an extension of Braid's original conceptualization of hypnosis[79][page number needed] as involving a process of enhancing or depressing the activity of the nervous system. Systems theory considers the nervous system's organization into interacting subsystems. Hypnotic phenomena thus involve not only increased or decreased activity of particular subsystems, but also their interaction. A central phenomenon in this regard is that of feedback loops, familiar to systems theory, which suggest a mechanism for creating the more extreme hypnotic phenomena.[80][81]

[edit] See also

[edit] Historical figures

- Franz Mesmer

- James Braid (physician)

- Abbé Faria

- Marquis de Puységur

- James Esdaile

- John Elliotson

- Jean-Martin Charcot

- Étienne Eugène Azam

- Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault

- John Milne Bramwell

- Hippolyte Bernheim

- Jean-Martin Charcot

- Pierre Janet

- Sigmund Freud

- Émile Coué

- Morton Prince

- Vladimir Bekhterev

[edit] Modern researchers

- Clark L. Hull

- George Estabrooks

- Milton Erickson

- Hans Eysenck

- Martin Orne

- Nicholas Spanos

- Theodore Sarbin

- Ernest R. Hilgard

- Jack Stanley Gibson

- Etzel Cardeña

[edit] Related subjects

- Chicken hypnosis

- Covert hypnosis

- Highway hypnosis

- History of hypnosis

- Hypnagogia

- Hypnofetishism

- Hypnosis in popular culture

- Hypnosurgery

- Hypnotherapy

- Hypnotherapy in childbirth

- Sedative (also known as sedative-hypnotic drug)

- Scientology and hypnosis

[edit] Organizations

- British Society of Clinical Hypnosis

- American Society of Clinical Hypnosis

- International Medical and Dental Hypnotherapy Association

- International Association of Counselors and Therapists

- National Guild of Hypnotists

[edit] References

- ^ "Information for the Public. American Society of Clinical Hypnosis."[1]

- ^ Lyda, Alex. "Hypnosis Gaining Ground in Medicine." Columbia News. [2]

- ^ p. 22, Spiegel, Herbert and Spiegel, David. Trance and Treatment. Basic Books Inc., New York. 1978. ISBN 0-465-08687-X

- ^ Braid, J. (1843) Neurypnology.

- ^ Bausell, R Barker, quoted in The Skeptic's Dictionary [3]

- ^ Braid, Neurypnology, 1843: 'Introduction'

- ^ Braid, Hypnotic Therapeutics, 1853

- ^ "New Definition: Hypnosis" Society of Psychological Hypnosis Division 30 - American Psychological Association [4].

- ^ Braid, Neurypnology, 1843

- ^ White, Robert W. 'A preface to the theory of hypnotism', Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology, 1941, 1, 498.

- ^ Waterfield, R. (2003). Hidden Depths: The Story of Hypnosis. pp. 36-37

- ^ Gulliford, Tristan. "Music and Trance in Siberian Shamanism." [5]

- ^ Braid, J. “Magic, Mesmerism, Hypnotism, etc., Historically and Physiologically considered”, 1844-1845, vol. XI., pp. 203-204, 224-227, 270-273, 296-299, 399-400, 439-41.

- ^ Braid, J. (1846). The Power of the Mind over the Body

- ^ Braid, J. Magic, Witchcraft, etc., 1852: 41-42.

- ^ Stewart, D. Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind, 1827: 147

- ^ Braid, Observations on Trance or Human Hibernation, 1850, 'Preface.'

- ^ A classic example of the ideomotor principle in action is the so-called "Chevreul pendulum" (named after Michel Eugène Chevreul). A pendulum can be made to swing, apparently of its own accord, as a result of concentration upon the idea of its doing so.

- ^ S. Freud, Lines of Advance in Psychoanalytic Therapy, 1919

- ^ Weitzenhoffer, The Practice of Hypnotism, 2000: 419

- ^ Sarbin, T.R. & Coe, W.C. (1972). Hypnosis: A Social Psychological Analysis of Influence Communication.

- ^ Barber, Spanos & Chaves (1974). Hypnotism: Imagination & Human Potentialities.

- ^ Alladin, A. (2008). Cognitive Hypnotherapy.

- ^ Chapman, R.A. (ed.) (2005). The Clinical Use of Hypnosis in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: A Practitioners Casebook

- ^ Wolpe, J. (1958) Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition.

- ^ Ellis, A. (1962). Reason & Emotion in Psychotherapy.

- ^ Barber, Spanos & Chaves (1974). Hypnotism: Imagination & Human Potentialities.

- ^ Hull, C.L. (1933). Hypnosis & Suggestibility.

- ^ Braid, J. (1843). Neurypnology.

- ^ "Clinical Research." hypnotic-tracks.us [6]

- ^ "Hypnosis for Pain." webmd.com [7]

- ^ Kirsch, Irving. "Hypnotic Enhancement of Cognitive-Behavioural Weight Loss Treatments--Another Meta-reanalysis." Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, v64 n3 p517-19 Jun 1996 [8]

- ^ Shenefelt, Philip D. "Applying Hypnosis in Dermatology." medscape.com. 6 January 2004 [9]

- ^ Barrett, Dierdre. "The Power of Hypnosis." Psychology Today. Jan/Feb 2001. [10]

- ^ "Hypnosis. Another Way to Manage Pain, Kick Bad Habits." mayoclinic.com [11]

- ^ Vickers, Andrew and Zollman, Catherine. "Clinical review. ABC of complementary medicine. Hypnosis and relaxation therapies." (BMJ) British Medical Journal 1999;319:1346-1349 ( 20 November ) [12]

- ^ "Hypnosis and Sport Performance." awss.com [13]

- ^ "History of the Stage Hypnotist and Stage Hypnosis Shows." [14]

- ^ "Discovery Health: All About Hypnobirthing," health.discovery.com [15]

- ^ Moore, M. & Tasso, A.F. 'Clinical hypnosis: the empirical evidence' in The Oxford Handbook of Hypnosis, 2008: 719-718.

- ^ http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/IBSFullGuideline.pdf NICE Guidance for IBS

- ^ "Physician Studies Hypnosis As Sedation Alternative," University of Iowa News Service, 6 February 2003 [16]

- ^ "Pain Decreases Under Hypnosis," medicalnewstoday.com [17]

- ^ "Hypnosis in Surgery," institute-shot.com [18]

- ^ "Hypnosis: Another way to manage pain, kick bad habits." Mayo Clinic. [19]

- ^ a b c Nash, Michael R. "The Truth and the Hype of Hypnosis". Scientific American: July 2001

- ^ Spiegel, D. and Moore, R. (1997) "Imagery and hypnosis in the treatment of cancer patients" Oncology 11(8): pp. 1179-1195

- ^ Garrow, D. and Egede, L. E. (November 2006) "National patterns and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use in adults with diabetes" Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 12(9): pp. 895-902

- ^ Mascot, C. (2004) "Hypnotherapy: A complementary therapy with broad applications" Diabetes Self Management 21(5): pp.15-18

- ^ Kwekkeboom, K.L. and Gretarsdottir, E. (2006) "Systematic review of relaxation interventions for pain" Journal of Nursing Scholarship 38(3): pp.269-277

- ^ Montgomery GH, et al. "A Randomized Clinical Trial of a Brief Hypnosis Intervention to Control Side Effects in Breast Surgery Patients." J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007 Sep 5;99(17):1280-1.

- ^ Montgomery, Guy. "Reducing Pain After Surgery Via Hypnosis". Your Cancer Today. http://www.yourcancertoday.com/news/hypnosis-surgery.html.

- ^ Shenefelt, Philip D. "Hypnosis: Applications in Dermatology and Dermatological Surgery." emedicine.com. [20]

- ^ Kirsch, Irving. "Hypnotic enhancement of cognitive-behavioural weight loss treatments : Another meta-reanalysis." Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. [21]

- ^ "Hypnosis." Wordnet search. [22]

- ^ Dubin, William. "Compulsive Gaming" (2006)[23]

- ^ "Cognitive Hypnotherapy: An Integrated Approach to the Treatment of Emotional Disorders." [24]

- ^ O'Connor, Anahad. "The Claim: Hypnosis Can Help You Quit Smoking." [25]

- ^ "Hypnotherapy for Smoking Cessation Sees Strong Results." ScienceDaily. [26]

- ^ "Questions and Answers about Memories of Childhood Abuse". American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pubinfo/mem.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-22.

- ^ Astin, J.A. et al. (2003) "Mind-body medicine: state of the science, implications for practice" Journal of the American Board of Family Practitioners 16(2): pp.131-147

- ^ "Self-hypnosis as a skill for busy research workers." London's Global University Human Resources. [27].

- ^ Yapko, Michael (1990). Trancework: An introduction to the practice of Clinical Hypnosis. NY, New York: Brunner/Mazel. pp. 28.

- ^ Wagstaff, Graham F. (1981) Hypnosis, Compliance and Belief St. Martin's Press, New York, ISBN 0312401574

- ^ McGill, Ormond (1996) The New Encyclopedia of Stage Hypnosis, p. 506

- ^ André M. Weitzenbhoffer. The Practice of Hypnotism 2nd ed, Toronto, John Wiley & Son Inc, Chapter 16, p. 583-587, 2000 ISBN 0-471-29790-9

- ^ Wier, Dennis R (1996). Trance: from magic to technology. Ann Arbor, Michigan: TransMedia. ISBN 1888428384.

- ^ White, R.W. 'A preface to the theory of hypnotism', Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 36, 477-505, October, 1941

- ^ Hull, Hypnosis & Suggestibility, 1933: 392

- ^ Pavlov, quoted in Salter, What is Hypnosis?, 1944: 23

- ^ Pavlov, I. P.: Experimental Psychology. New York, Philosophical Library, 1957.

- ^ Psychosomatic Medicine. http://www.psychosomaticmedicine.org/cgi/content/abstract/10/6/317

- ^ Horton & Crawford, in Heap et al., The Highly Hypnotisable Subject, 2004: 140.

- ^ Gosline, Anna (2004-09-10). "Hypnosis really changes your mind". New Scientist. http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn6385. Retrieved on 2007-08-27.

- ^ Weitzenhoffer, A.M.: Hypnotism - An Objective Study in Suggestibility. New York, Wiley, 1953.

- ^ Baron's AP Psychology 2008

- ^ Baker, Robert A. (1990) They Call It Hypnosis Prometheus Books, Buffalo, NY, ISBN 0879755768

- ^ Kroger, William S. (1977) Clinical and experimental hypnosis in medicine, dentistry, and psychology. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 31. ISBN 0-397-50377-6

- ^ Braid J (1843). Neurypnology or The rationale of nervous sleep considered in relation with animal magnetism.. Buffalo, N.Y.: John Churchill.

- ^ Morgan J.D. (1993). The Principles of Hypnotherapy. Eildon Press.

- ^ "electronic copy of The Principles of Hypnotherapy". http://www.hypno1.co.uk/BookPrinciplesHypnosis.htm. Retrieved on 2007-01-22.

[edit] External links

| Look up hypnosis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Hypnosis at the Open Directory Project