Scanning electron microscope

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

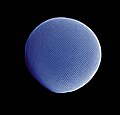

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) is a type of electron microscope that images the sample surface by scanning it with a high-energy beam of electrons in a raster scan pattern. The electrons interact with the atoms that make up the sample producing signals that contain information about the sample's surface topography, composition and other properties such as electrical conductivity.

The types of signals produced by an SEM include secondary electrons, back scattered electrons (BSE), characteristic x-rays, light (cathodoluminescence), specimen current and transmitted electrons. These types of signal all require specialized detectors for their detection that are not usually all present on a single machine. The signals result from interactions of the electron beam with atoms at or near the surface of the sample. In the most common or standard detection mode, secondary electron imaging or SEI, the SEM can produce very high-resolution images of a sample surface, revealing details about 1 to 5 nm in size. Due to the way these images are created, SEM micrographs have a very large depth of field yielding a characteristic three-dimensional appearance useful for understanding the surface structure of a sample. This is exemplified by the micrograph of pollen shown to the right. A wide range of magnifications is possible, from about x 25 (about equivalent to that of a powerful hand-lens) to about x 250,000, about 250 times the magnification limit of the best light microscopes. Back-scattered electrons (BSE) are beam electrons that are reflected from the sample by elastic scattering. BSE are often used in analytical SEM along with the spectra made from the characteristic x-rays. Because the intensity of the BSE signal is strongly related to the atomic number (Z) of the specimen, BSE images can provide information about the distribution of different elements in the sample. For the same reason BSE imaging can image colloidal gold immuno-labels of 5 or 10 nm diameter, that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to detect in secondary electron images in biological specimens. Characteristic X-rays are emitted when the electron beam removes an inner shell electron from the sample, causing a higher energy electron to fill the shell and release energy. These characteristic x-rays are used to identify the composition and measure the abundance of elements in the sample.

[edit] History

The first SEM image was obtained by Max Knoll, who in 1935 obtained an image of silicon steel showing electron channeling contrast.[1] Further pioneering work on the physical principles of the SEM and beam specimen interactions was performed by Manfred von Ardenne in 1937,[2][3] who produced a British patent[4] but never made a practical instrument. The SEM was further developed by Professor Sir Charles Oatley and his postgraduate student Gary Stewart and was first marketed in 1965 by the Cambridge Instrument Company as the "Stereoscan". The first instrument was delivered to DuPont.

[edit] Scanning process and image formation

In a typical SEM, an electron beam is thermionically emitted from an electron gun fitted with a tungsten filament cathode. Tungsten is normally used in thermionic electron guns because it has the highest melting point and lowest vapour pressure of all metals, thereby allowing it to be heated for electron emission, and because of its low cost. Other types of electron emitters include lanthanum hexaboride (LaB6) cathodes, which can be used in a standard tungsten filament SEM if the vacuum system is upgraded and field emission guns (FEG), which may be of the cold-cathode type using tungsten single crystal emitters or the thermally-assisted Schottky type, using emitters of zirconium oxide.

The electron beam, which typically has an energy ranging from a few hundred eV to 40 keV, is focused by one or two condenser lenses to a spot about 0.4 nm to 5 nm in diameter. The beam passes through pairs of scanning coils or pairs of deflector plates in the electron column, typically in the final lens, which deflect the beam in the x and y axes so that it scans in a raster fashion over a rectangular area of the sample surface.

When the primary electron beam interacts with the sample, the electrons lose energy by repeated random scattering and absorption within a teardrop-shaped volume of the specimen known as the interaction volume, which extends from less than 100 nm to around 5 µm into the surface. The size of the interaction volume depends on the electron's landing energy, the atomic number of the specimen and the specimen's density. The energy exchange between the electron beam and the sample results in the reflection of high-energy electrons by elastic scattering, emission of secondary electrons by inelastic scattering and the emission of electromagnetic radiation, each of which can be detected by specialized detectors. The beam current absorbed by the specimen can also be detected and used to create images of the distribution of specimen current. Electronic amplifiers of various types are used to amplify the signals which are displayed as variations in brightness on a cathode ray tube. The raster scanning of the CRT display is synchronised with that of the beam on the specimen in the microscope, and the resulting image is therefore a distribution map of the intensity of the signal being emitted from the scanned area of the specimen. The image may be captured by photography from a high resolution cathode ray tube, but in modern machines is digitally captured and displayed on a computer monitor and saved to a computer's hard disc.

[edit] Magnification

Magnification in a SEM can be controlled over a range of up to 6 orders of magnitude from about x25 to x 250,000 and exceptionally to 2 million times in the Hitachi S-5500 in-lens Field Emission SEM, imaging a specimen area about 60nm wide with resolution up to 0.4 nm. Unlike optical and transmission electron microscopes, image magnification in the SEM is not a function of the power of the objective lens. SEMs may have condenser and objective lenses, but their function is to focus the beam to a spot, and not to image the specimen. Provided the electron gun can generate a beam with sufficiently small diameter, an SEM could in principle work entirely without condenser or objective lenses, although it might not be very versatile or achieve very high resolution. In an SEM, as in scanning probe microscopy, magnification results from the ratio of the dimensions of the raster on the specimen and the raster on the display device. Assuming that the display screen has a fixed size, higher magnification results from reducing the size of the raster on the specimen, and vice versa. Magnification is therefore controlled by the current supplied to the x,y scanning coils, and not by objective lens power.

[edit] Sample preparation

All samples must also be of an appropriate size to fit in the specimen chamber and are generally mounted rigidly on a specimen holder called a specimen stub. Several models of SEM can examine any part of a 6-inch (15 cm) semiconductor wafer, and some can tilt an object of that size to 45 degrees.

For conventional imaging in the SEM, specimens must be electrically conductive, at least at the surface, and electrically grounded to prevent the accumulation of electrostatic charge at the surface. Metal objects require little special preparation for SEM except for cleaning and mounting on a specimen stub. Nonconductive specimens tend to charge when scanned by the electron beam, and especially in secondary electron imaging mode, this causes scanning faults and other image artifacts. They are therefore usually coated with an ultrathin coating of electrically-conducting material, commonly gold, deposited on the sample either by low vacuum sputter coating or by high vacuum evaporation. Conductive materials in current use for specimen coating include gold, gold/palladium alloy, platinum, osmium,[5] iridium, tungsten, chromium and graphite. Coating prevents the accumulation of static electric charge on the specimen during electron irradiation.

Two important reasons for coating, even when there is more than enough specimen conductivity to prevent charging, are to maximise signal and improve spatial resolution, especially with samples of low atomic number (Z). Broadly, signal increases with atomic number, especially for backscattered electron imaging. The improvement in resolution arises because in low-Z materials such as carbon, the electron beam can penetrate several micrometres below the surface, generating signals from an interaction volume much larger than the beam diameter and reducing spatial resolution. Coating with a high-Z material such as gold maximises secondary electron yield from within a surface layer a few nm thick, and suppresses secondary electrons generated at greater depths, so that the signal is predominantly derived from locations closer to the beam and closer to the specimen surface than would be the case in an uncoated, low-Z material. These effects are particularly, but not exclusively, relevant to biological samples.

An alternative to coating for some biological samples is to increase the bulk conductivity of the material by impregnation with osmium using variants of the OTO process.[6][7] Nonconducting specimens may be imaged uncoated using specialized SEM instrumentation such as the "Environmental SEM" (ESEM) or field emission gun (FEG) SEMs operated at low voltage. Environmental SEM instruments place the specimen in a relatively high pressure chamber where the working distance is short and the electron optical column is differentially pumped to keep vacuum adequately low at the electron gun. The high pressure region around the sample in the ESEM neutralizes charge and provides an amplification of the secondary electron signal. Low voltage (LV) SEM of non-conducting specimens can be operationally difficult to accomplish in a conventional SEM and is typically a research application for specimens that are sensitive to the process of applying conductive coatings. LV-SEM is typically conducted in an FEG-SEM because the FEG is capable of producing high primary electron brightness even at low accelerating potentials. Operating conditions must be adjusted such that the local space charge is at or near neutral with adequate low voltage secondary electrons being available to neutralize any positively charged surface sites. This requires that the primary electron beam's potential and current be tuned to the characteristics of the sample specimen.

Embedding in a resin with further polishing to a mirror-like finish can be used for both biological and materials specimens when imaging in backscattered electrons or when doing quantitative X-ray microanalysis.

[edit] Biological samples

For SEM, a specimen is normally required to be completely dry, since the specimen chamber is at high vacuum. Hard, dry materials such as wood, bone, feathers, dried insects or shells can be examined with little further treatment, but living cells and tissues and whole, soft-bodied organisms usually require chemical fixation to preserve and stabilize their structure. Fixation is usually performed by incubation in a solution of a buffered chemical fixative, such as glutaraldehyde, sometimes in combination with formaldehyde[8][9][10] and other fixatives,[11] and optionally followed by postfixation with osmium tetroxide.[8] The fixed tissue is then dehydrated. Because air-drying causes collapse and shrinkage, this is commonly achieved by critical point drying, which involves replacement of water in the cells with organic solvents such as ethanol or acetone, and replacement of these solvents in turn with a transitional fluid such as liquid carbon dioxide at high pressure. The carbon dioxide is finally removed while in a supercritical state, so that no gas-liquid interface is present within the sample during drying. The dry specimen is usually mounted on a specimen stub using an adhesive such as epoxy resin or electrically-conductive double-sided adhesive tape, and sputter coated with gold or gold/palladium alloy before examination in the microscope.

If the SEM is equipped with a cold stage for cryo-microscopy, cryofixation may be used and low-temperature scanning electron microscopy performed on the cryogenically fixed specimens.[8] Cryo-fixed specimens may be cryo-fractured under vacuum in a special apparatus to reveal internal structure, sputter coated and transferred onto the SEM cryo-stage while still frozen.[12] Low-temperature scanning electron microscopy is also applicable to the imaging of temperature-sensitive materials such as ice[13][14] (see e.g. illustration at right) and fats.[15]

Freeze-fracturing, freeze-etch or freeze&break is a preparation method particularly useful for examining lipid membranes and their incorporated proteins in "face on" view. The preparation method reveals the proteins embedded in the lipid bilayer.

Gold has a high atomic number and sputter coating with gold produces high topographic contrast and resolution. However, the coating has a thickness of a few micrometres, and can obscure the underlying fine detail of the specimen at very high magnification. Low-vacuum SEMs with differential pumping apertures allow samples to be imaged without such coating and without the loss of natural contrast caused by the coating, but are unable to achieve the resolution attainable by conventional SEMs with coated specimens.

[edit] Materials

Back scattered electron imaging, quantitative x-ray analysis, and x-ray mapping of geological specimens and metals requires that the surfaces be ground and polished to an ultra smooth surface. Geological specimens that undergo WDS or EDS analysis are often carbon coated. Metals are not generally coated prior to imaging in the SEM because they are conductive and provide their own pathway to ground.

Fractography is the study of fractured surfaces that can be done on a light microscope or commonly, on an SEM. The fractured surface is cut to a suitable size, cleaned of any organic residues, and mounted on a specimen holder for viewing in the SEM.

Integrated circuits may be cut with a FIB or other ion beam milling instrument for viewing in the SEM. The SEM in the first case may be incorporated into the FIB.

Metals, geological specimens, and integrated circuits all may also be chemically polished for viewing in the SEM.

Special high resolution coating techniques are required for high magnification imaging of inorganic thin films.

[edit] ESEM

The accumulation of electric charge on the surfaces of non-metallic specimens can be avoided by using environmental SEM in which the specimen is placed in an internal chamber at higher pressure than the vacuum in the electron optical column. Positively charged ions generated by beam interactions with the gas help to neutralize the negative charge on the specimen surface. The pressure of gas in the chamber can be controlled, and the type of gas used can be varied according to need. Coating is thus unnecessary, and X-ray analysis unhindered.

[edit] Detection of secondary electrons

The most common imaging mode collects low-energy (<50 eV) secondary electrons that are ejected from the k-orbitals of the specimen atoms by inelastic scattering interactions with beam electrons. Due to their low energy, these electrons originate within a few nanometers from the sample surface.[16] The electrons are detected by an Everhart-Thornley detector[17] which is a type of scintillator-photomultiplier system. The secondary electrons are first collected by attracting them towards an electrically-biased grid at about +400V, and then further accelerated towards a phosphor or scintillator positively biased to about +2000V. The accelerated secondary electrons are now sufficiently energetic to cause the scintillator to emit flashes of light (cathodoluminescence) which are conducted to a photomultiplier outside the SEM column via a light pipe and a window in the wall of the specimen chamber. The amplified electrical signal output by the photomultiplier is displayed as a two-dimensional intensity distribution that can be viewed and photographed on an analogue video display, or subjected to analog-to-digital conversion and displayed and saved as a digital image. This process relies on a raster-scanned primary beam. The brightness of the signal depends on the number of secondary electrons reaching the detector. If the beam enters the sample perpendicular to the surface, then the activated region is uniform about the axis of the beam and a certain number of electrons "escape" from within the sample. As the angle of incidence increases, the "escape" distance of one side of the beam will decrease, and more secondary electrons will be emitted. Thus steep surfaces and edges tend to be brighter than flat surfaces, which results in images with a well-defined, three-dimensional appearance. Using this technique, image resolution less than 1 nm is possible.

[edit] Detection of backscattered electrons

Backscattered electrons (BSE) consist of high-energy electrons originating in the electron beam, that are reflected or back-scattered out of the specimen interaction volume by elastic scattering interactions with specimen atoms. Since heavy elements (high atomic number) backscatter electrons more strongly than light elements (low atomic number), and thus appear brighter in the image, BSE are used to detect contrast between areas with different chemical compositions.[16] The Everhart-Thornley detector, which is normally positioned to one side of the specimen, is inefficient for the detection of backscattered electrons because few such electrons are emitted in the solid angle subtended by the detector, and because the positively biased detection grid has little ability to attract the higher energy BSE electrons. Dedicated backscattered electron detectors are positioned above the sample in a "doughnut" type arrangement, concentric with the electron beam, maximising the solid angle of collection. BSE detectors are usually either of scintillator or semiconductor types. When all parts of the detector are used to collect electrons symmetrically about the beam, atomic number contrast is produced. However, strong topographic contrast is produced by collecting back-scattered electrons from one side above the specimen using an asymmetrical, directional BSE detector; the resulting contrast appears as illumination of the topography from that side. Semiconductor detectors can be made in radial segments that can be switched in or out to control the type of contrast produced and its directionality.

Backscattered electrons can also be used to form an electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) image that can be used to determine the crystallographic structure of the specimen.

[edit] Beam-injection analysis of semiconductors

The nature of the SEM's probe, energetic electrons, makes it uniquely suited to examining the optical and electronic properties of semiconductor materials. The high-energy electrons from the SEM beam will inject charge carriers into the semiconductor. Thus, beam electrons lose energy by promoting electrons from the valence band into the conduction band, leaving behind holes.

In a direct bandgap material, recombination of these electron-hole pairs will result in cathodoluminescence; if the sample contains an internal electric field, such as is present at a p-n junction, the SEM beam injection of carriers will cause electron beam induced current (EBIC) to flow.

Cathodoluminescence and EBIC are referred to as "beam-injection" techniques, and are very powerful probes of the optoelectronic behavior of semiconductors, particularly for studying nanoscale features and defects.

[edit] Cathodoluminescence

Cathodoluminescence, the emission of light when atoms excited by high-energy electrons return to their ground state, is analogous to UV-induced fluorescence, and some materials such as zinc sulfide and some fluorescent dyes, exhibit both phenomena. Cathodoluminescence is most commonly experienced in everyday life as the light emission from the inner surface of the cathode ray tube in television sets and computer CRT monitors. In the SEM, CL detectors either collect all light emitted by the specimen, or can analyse the wavelengths emitted by the specimen and display an emission spectrum or an image of the distribution of cathodoluminescence emitted by the specimen in real colour.

[edit] X-ray microanalysis

X-rays, which are also produced by the interaction of electrons with the sample, may also be detected in an SEM equipped for energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy or wavelength dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.

[edit] Resolution of the SEM

The spatial resolution of the SEM depends on the size of the electron spot, which in turn depends on both the wavelength of the electrons and the electron-optical system which produces the scanning beam. The resolution is also limited by the size of the interaction volume, or the extent to which the material interacts with the electron beam. The spot size and the interaction volume are both large compared to the distances between atoms, so the resolution of the SEM is not high enough to image individual atoms, as is possible in the shorter wavelength (i.e. higher energy) transmission electron microscope (TEM). The SEM has compensating advantages, though, including the ability to image a comparatively large area of the specimen; the ability to image bulk materials (not just thin films or foils); and the variety of analytical modes available for measuring the composition and proprties of the specimen. Depending on the instrument, the resolution can fall somewhere between less than 1 nm and 20 nm. The world's highest SEM resolution is obtained with the Hitachi S-5500. Resolution is 0.4nm at 30kV and 1.6nm at 1kV. In general, SEM images are easier to interpret than TEM images.

[edit] Environmental SEM

Conventional SEM requires samples to be imaged under vacuum, because a gas atmosphere rapidly spreads and attenuates electron beams. Consequently, samples that produce a significant amount of vapour, e.g. wet biological samples or oil-bearing rock need to be either dried or cryogenically frozen. Processes involving phase transitions, such as the drying of adhesives or melting of alloys, liquid transport, chemical reactions, solid-air-gas systems and living organisms in general cannot be observed.

The first commercial development of the Environmental SEM (ESEM) in the late 1980s [18] [19] allowed samples to be observed in low-pressure gaseous environments (e.g. 1-50 Torr) and high relative humidity (up to 100%). This was made possible by the development of a secondary-electron detector [20] [21] capable of operating in the presence of water vapour and by the use of pressure-limiting apertures with differential pumping in the path of the electron beam to separate the vacuum regions around the gun and lenses from the sample chamber.

The first commercial ESEMs were produced by the ElectroScan Corporation in USA in 1988 [22]. ElectroScan were later taken over by Philips (now FEI Company) in 1996 [23].

ESEM is especially useful for non-metallic and biological materials because coating with carbon or gold is unnecessary. Uncoated Plastics and Elastomers can be routinely examined, as can uncoated biological samples. Coating can be difficult to reverse, may conceal small features on the surface of the sample and may reduce the value of the results obtained. X-ray analysis is difficult with a coating of a heavy metal, so carbon coatings are routinely used in conventional SEMs, but ESEM makes it possible to perform X-ray microanalysis on uncoated non-conductive specimens. ESEM may be the preferred for electron microscopy of unique samples from criminal or civil actions, where forensic analysis may need to be repeated by several different experts.

[edit] See also

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Scanning electron microscopic images |

- List of surface analysis methods

- Forensic science

- Forensic engineering

- Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

[edit] Terminology

- DR-SEM

- Defect Review - Scanning Electron Microscopy

- CD-SEM

- Critical Dimension Measurement - Scanning Electron Microscopy

- FIB-SEM

- Focused Ion Beam - Scanning Electron Microscopy

- SBFSEM

- Serial Block-Face Scanning Electron Microscopy

- ESEM

- Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy

- FEGSEM

- field emission gun Scanning Electron Microscopy

[edit] References

- ^ Knoll, Max (1935). "Aufladepotentiel und Sekundäremission elektronenbestrahlter Körper". Zeitschrift für technische Physik 16: 467–475.

- ^ von Ardenne, Manfred (1938a). "Das Elektronen-Rastermikroskop. Theoretische Grundlagen" (in German). Zeitschrift für Physik 108 (9–10): 553–572. doi:.

- ^ von Ardenne, Manfred (1938b). "Das Elektronen-Rastermikroskop. Praktische Ausführung" (in German). Zeitschrift für technische Physik 19: 407–416.

- ^ von Ardenne M. Improvements in electron microscopes. GB patent 511204, convention date (Germany) 18 Feb 1937

- ^ Suzuki, E. (2002). "High-resolution scanning electron microscopy of immunogold-labelled cells by the use of thin plasma coating of osmium". Journal of Microscopy 208 (3): 153–157. doi:.

- ^ Seligman, Arnold M.; Wasserkrug, Hannah L.; Hanker, Jacob S. (1966). "A new staining method for enhancing contrast of lipid-containing membranes and droplets in osmium tetroxide-fixed tissue with osmiophilic thiocarbohydrazide (TCH)". Journal of Cell Biology 30 (2): 424–432. doi:.

- ^ Malick, Linda E.; Wilson, Richard B.; Stetson, David (1975). "Modified Thiocarbohydrazide Procedure for Scanning Electron Microscopy: Routine use for Normal, Pathological, or Experimental Tissues". Biotechnic and Histochemistry 50 (4): 265–269. doi:.

- ^ a b c Jeffree, C. E.; Read, N. D. (1991). "Ambient- and Low-temperature scanning electron microscopy". in Hall, J. L.; Hawes, C. R.. Electron Microscopy of Plant Cells. London: Academic Press. pp. 313–413. ISBN 0123188806.

- ^ Karnovsky, M. J. (1965). "A formaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixative of high osmolality for use in electron microscopy". Journal of Cell Biology 27: 137A–138A.

- ^ Kiernan, J. A. (2000). "Formaldehyde, formalin, paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde: What they are and what they do". Microscopy Today 2000 (1): 8–12.

- ^ Russell, S. D.; Daghlian, C. P. (1985). "Scanning electron microscopic observations on deembedded biological tissue sections: Comparison of different fixatives and embedding materials". Journal of Electron Microscopy Technique 2 (5): 489–495. doi:.

- ^ Faulkner, Christine; et al. (2008). "Peeking into Pit Fields: A Multiple Twinning Model of Secondary Plasmodesmata Formation in Tobacco". Plant Cell. doi:.

- ^ Wergin, W. P.; Erbe, E. F. (1994). "Snow crystals: capturing snow flakes for observation with the low-temperature scanning electron microscope". Scanning 16 (Suppl. IV): IV88–IV89.

- ^ Barnes, P. R. F.; Mulvaney, R.; Wolff, E. W.; Robinson, K. A. (2002). "A technique for the examination of polar ice using the scanning electron microscope". Journal of Microscopy 205 (2): 118–124. doi:.

- ^ Hindmarsh, J. P.; Russell, A. B.; Chen, X. D. (2007). "Fundamentals of the spray freezing of foods—microstructure of frozen droplets". Journal of Food Engineering 78 (1): 136–150. doi:.

- ^ a b Goldstein, G. I.; Newbury, D. E.; Echlin, P.; Joy, D. C.; Fiori, C.; Lifshin, E. (1981). Scanning electron microscopy and x-ray microanalysis. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 030640768X.

- ^ Everhart, T. E.; Thornley, R. F. M. (1960). "Wide-band detector for micro-microampere low-energy electron currents". Journal of Scientific Instruments 37: 246–248. doi:.

- ^ Danilatos, G,D (1988). "Foundations of environmental scanning electron microscopy". Advances in Electronics and Electron Physics 71: 109–250.

- ^ US4,823,006 (1989-4-18) Gerasimos D Danilatos, George C Lewis, Integrated electron optical/differential pumping/imaging signal detection system for an environmental scanning electron microscope.

- ^ Danilatos, G,D (1990). "Theory of the Gaseous Detector Device in the ESEM". Advances in Electronics and Electron Physics 78: 1–102.

- ^ US4,785,182 (1988-11-15) James F Mancuso, William B Maxwell, Gerasimos D Danilatos, Secondary Electron Detector for Use in a Gaseous Atmosphere.

- ^ History of Electron Microscopy, 1980s

- ^ History of Electron Microscopy 1990s

[edit] External links

[edit] General

- Notes on the SEM Notes covering all aspects of the SEM

[edit] History

- Microscopy History links from the University of Alabama Department of Biological Sciences

- The Early History and Development of SEM from Cambridge University Engineering Department

- Milestones in the History of Electron Microscopy from the Swiss Federal Institute of Zürich

- Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope (ESEM) history

[edit] Images

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Scanning electron microscopic images |

- SEMTech Solutions Image Gallery 3D-SEM, FE-SEM, and PLM images

- Tescan Image Gallery Some great SEM images of various specimens, as well as analytical results

- Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc. Large collection of SEM images - mostly false colour

- Jeol SEM Images Twelve SEM images of various specimens

- SEM Lab at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History; includes a gallery of images

- Rippel Electron Microscope Facility Many dozens of (mostly biological) SEM images from Dartmouth College.

[edit] Gallery of SEM images

The following are examples of images taken using a scanning electron microscope.

|

False coloured SEM image of soybean cyst nematode and egg. The false colour makes the image easier for non-specialists to view and understand the structures and surfaces revealed in micrographs. |

Compound eye of Antarctic krill Euphausia superba. Arthropod eyes are a common subject in SEM micrographs due to the depth of focus that an SEM image can capture. |

Ommatidia of Antarctic krill eye, a higher magnification of the krill's eye. SEMs cover a range from light microscopy up to the magnifications available with a TEM. |

SEM image of normal circulating human blood. This is an older and noisy micrograph of a common subject for SEM micrographs: red blood cells. |

|

SEM image of a hederelloid from the Devonian of Michigan (largest tube diameter is 0.75 mm). The SEM is used extensively for capturing detailed images of micro and macro fossils. |

Backscattered Electron (BSE) image of an Antimony rich region in a fragment of ancient glass. Museums use SEMs for studying valuable artifacts in a nondestructive manner. Many BSE images are taken at atmospheric rather than destructive high vacuum conditions. |

SEM image of a photoresist layer used in semiconductor manufacturing taken on a field emission SEM at 1000 volts, a very low accelerating voltage for an SEM, but achievable with field emission SEMs--this one taken with a Schottky field-emission gun. These SEMs are important in the semiconductor industry for their high resolution capabilities. |