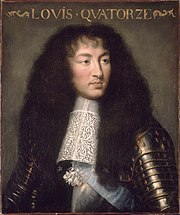

Louis XIV of France

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article may need to be rewritten entirely to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as Need for citations throughout the article; Editing for stylistic continuity. You can help. The discussion page may contain suggestions. (August 2008) |

| This article needs reorganization to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. There is good information here, but it is poorly organized; editors are encouraged to be bold and make changes to the overall structure to improve this article. (August 2008) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Louis XIV (5 September 1638 – 1 September 1715) ruled as King of France and of Navarre. He ascended the throne a few months before his fifth birthday, but did not assume actual personal control of the government until the death of his prime minister (Premier ministre), the Italian Jules Cardinal Mazarin, in 1661.[1] Louis remained on the throne until his death in September 1715, four days before his seventy-seventh birthday. His reign lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days, the longest documented for any European monarch to date.[2]

Louis XIV is popularly known as the Sun King (French: le Roi Soleil). Louis believed in the Divine Right of Kings, a theory which received one of its most classic expressions in "On the Duties of Kings", a sermon preached by Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet in Louis' presence in 1662. (Louis was so impressed with Bossuet that in 1670, he appointed Bossuet as tutor to Louis' son and heir.)

For much of Louis's reign, France stood as the leading power in Europe, engaging in three major wars—the Franco-Dutch War, the War of the League of Augsburg, and the War of the Spanish Succession—and two minor conflicts—the War of Devolution, and the War of the Reunions. Men who featured prominently in the political and military life of France during this period include Mazarin, Nicolas Fouquet, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Michel Le Tellier, Le Tellier's son Louvois, le Grand Condé, Turenne, Vauban, Villars and Tourville. French culture likewise flourished during this era, producing a number of figures of great renown, including Molière, Racine, Boileau, La Fontaine, Lully, Le Brun, Rigaud, Louis Le Vau, Jules Hardouin Mansart, Claude Perrault and Le Nôtre.

Louis XIV continued the work of his predecessors to create a centralized state governed from the capital in order to sweep away the remnants of feudalism which had persisted in parts of France. He succeeded in breaking the power of the provincial nobility, much of which had risen in revolt during his minority, and forced many leading nobles to live with him in his lavish Palace of Versailles. Consequently, he has long been considered the archetypal absolute monarch of early modern Europe. Louis is reported to have said on his death bed: "Je m'en vais, mais l'État demeurera toujours." ("I depart, but the State shall always remain").[3]

[edit] Birth and ancestry

The future Louis XIV was born in the château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 5 September 1638 and bore the heir apparent's traditional title of Dauphin.[4] His birth came after the almost twenty-three years of childlessness of his estranged parents, Louis XIII and Anne of Austria. As a result, contemporaries regarded him as a divine gift and some saw his birth as a miracle[5][6][7].

Louis' ancestors came from some of Europe's most noteworthy ruling houses. Genealogist C. Carretier calculated Louis XIV's ancestry to the eighth generation, finding his ancestry to be approximately 36% Spanish, 28% French, 11% German and 8% Italian, the rest being Slavic, English, Savoyard and Lorrainian.[8] His paternal grandparents were Henri IV of France and Marie de' Medici, who were French and Italian respectively; while both his maternal grandparents were Habsburgs, Philip III of Spain and Margaret of Austria. In this manner, he counted as his ancestors various historical figures, including Charles V and Frederick Barbarossa, both Holy Roman Emperors. He was also the great grandson of Phillip II of Spain and thus a descendent of Queen Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, the Catholic Monarchs. He also descended from the founder of Russia's first dynasty, Rurik the Viking, as well as Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, the poet Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Giovanni de' Medici, last of the great condottieri. Most importantly, he traced his paternal lineage, and hence his and his descendants' right to the throne, in unbroken legitimate male succession from Saint Louis, King of France, and through him, from Hugh Capet.

Louis XIII and Anne had a second child, Philippe I, duc d'Orléans in 1640. Unsure of Anne as regent, Louis XIII decreed that a regency council, of which she was named head, should rule in Louis's name in the event he succeeded to the throne before the age of majority.

[edit] Minority and the Fronde

On 14 May 1643, after Louis XIII died and his young son became Louis XIV, Anne had her husband's will annulled by the Parlement, did away with the regency council and became the sole regent. She entrusted power to Cardinal Mazarin.

The Thirty Years' War, which had commenced during the previous reign of Louis XIII, ended in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia, made up of the Treaties of Münster and Osnabrück, the work of Mazarin. This Peace ensured Dutch independence from Spain, awarded a degree of autonomy to the various German princes and granted Sweden territories which gave her control of the mouths of the Oder, Elbe, and Weser, as well as seats on the Reichstag. It marked the apogee of Swedish power and influence in German and European affairs. However, it was France which had the most to gain from the terms of the Peace. Austria ceded to France all Habsburg lands and claims in Alsace; and the petty German states eager to dislodge themselves from Habsburg domination placed themselves under French protection, paving the way for the formation of the League of the Rhine in 1658 and leading to the further diminution of Imperial power.

In the closing years of the Thirty Years' War, a civil war known as the Fronde, which effectively curbed France's ability to make good the advantages gained in the Peace of Westphalia, broke out. The Frondeurs originally sought to protect traditional feudal rights from an increasingly centralized and centralizing royal government, as Cardinal Mazarin had continued to largely follow the policies of his predecessor, Cardinal Richelieu, seeking to augment the power of the Crown at the expense of the nobility and the Parlements. In 1648, he sought to levy a tax on the members of the Parlement de Paris, a judicial body composed mostly of nobles and high clergymen. The members of the Parlement not only refused to comply, but also ordered all of Cardinal Mazarin's earlier financial edicts burned. When Mazarin, strengthened by the news of the victory of Louis II de Bourbon, prince de Condé (le Grand Condé) at the Battle of Lens, arrested certain members of the Parlement in a show of force, Paris erupted in rioting and insurrection. A mob of angry Parisians broke into the royal palace and demanded to see their king. Led into the royal bedchamber, they gazed upon Louis XIV, who was feigning sleep, and quietly departed. Prompted by the possible danger to the royal family and the monarchy, Anne fled Paris with the king and his courtiers. Shortly thereafter, the signing of the Peace of Westphalia allowed the French army under Condé to return to the aid of Louis XIV and his royal court.

After the first Fronde (Fronde parlementaire, 1648-1649) ended, the second Fronde, that of the nobles (Fronde des princes, 1650-1653) began. This second phase of upper-class insurrection, unlike that which preceded it, was characterized by tales of sordid intrigue and half-hearted warfare. It was conducted by aristocrats for whom it represented a protest against and an attempt to reverse the centralisation of France and their consequent demotion from vassals to courtiers. This Fronde was led by France's highest-ranking nobles, from Louis' uncle Gaston, duc d'Orléans, and first cousin, Anne d'Orléans, duchesse de Montpensier (known as la Grande Mademoiselle); to more distantly-related princes du sang such as Condé, his brother Armand de Bourbon, prince de Conti, and their sister Anne-Geneviève, duchesse de Longueville; to dukes of legitimated royal descent, like Henri II d'Orléans, duc de Longueville, and François de Bourbon-Vendôme, duc de Beaufort; and to princelings descended from foreign dynasties (known as princes étrangers), such as Frédéric Maurice de La Tour d'Auvergne, duc de Bouillon, and his brother, the famous Marshal of France, Henri, vicomte de Turenne, as well as Marie de Rohan-Montbazon, duchesse de Chevreuse; and scions of France's oldest families, like François VI, duc de La Rochefoucauld. With the coming of age of Louis XIV and his subsequent coronation, the Frondeurs, who could hitherto have claimed to have been acting on his behalf and in his real interests against his mother and her first minister, had lost their pretext for revolt. The Fronde thus gradually lost steam until it ended in 1653, when Mazarin returned triumphant from abroad after having fled into exile on several occasions.

[edit] Personal reign and reforms

Within France, upon the death of Cardinal Mazarin, his first minister, in 1661, Louis XIV assumed personal control of the reins of government. He was able to exploit the widespread public yearning for peace and order, which had resulted from the long foreign wars and domestic civil strife, caused by events such as the Fronde and abuses of the people perpetrated by some nobles, to consolidate central authority at the feudal aristocracy's expense.

At the same time, the French treasury stood close to bankruptcy. Louis XIV eliminated Nicolas Fouquet, the Surintendant des Finances, commuting the sentence of banishment, passed by the Parlement, to imprisonment for life, and abolished Fouquet's office. Jean-Baptiste Colbert was appointed as Contrôleur général des Finances in 1665. To be sure, Fouquet had committed no financial indiscretions which Mazarin had not committed before him and which Colbert would not commit afterward.

The commencement of Louis's personal reign was marked by a series of administrative and fiscal reforms. Colbert reduced the national debt through more efficient taxation. His principal taxes included the aides, the douanes, the gabelle, and the taille. The aides and douanes were customs duties, the gabelle a tax on salt, and the taille a tax on land.

Colbert also had wide-ranging plans to strengthen France through commerce and trade. His administration ordained new industries and encouraged manufacturers and inventors, such as the Lyon silk manufacturers and the Manufacture des Gobelins, which produced and still produces tapestries. He also brought professional manufacturers and artisans from all over Europe, such as glassmakers from Murano, ironworkers from Sweden, and shipbuilders from the United Provinces. In this manner, he sought to decrease French dependence on foreign imported goods while increasing French exports, and hence to decrease the flow of gold and silver out of France.

Le Tellier and Louvois had an important role to play in government, curbing the independent spirit of much of the nobility at court and in the army. Gone were the days when army generals, without regard to the bigger political and diplomatic picture, protracted war at the frontiers and disobeyed orders coming from the capital, while quarrelling and bickering with each other over precedence. Gone too were the days when positions of seniority and rank in the army were the sole possession of the old military aristocracy (the noblesse d'épée). Louvois, in particular, pledged himself to modernizing the army, organizing it into a new professional, disciplined and well-trained force out of the old. He sought to contrive and direct campaigns and devoted himself to providing for the soldiers' material well-being and morale, and he did so successfully.

Louis also instituted various legal reforms. This is reflected in the sheer number of Great Ordinances (Grandes Ordonnances) enacted during his reign. The Grande Ordonnance de Procédure Civile of 1667, also known as Code Louis, was a comprehensive legal code regulating civil procedure in all of France in a uniform manner. It made it compulsory to record baptisms, marriages and burials in the registers of the State (as opposed to the registers of the Church). The Code Louis played an important part in France's legal history as it was the basis for Napoleon I's Code Napoléon, which is itself the basis for many of Western Europe's modern legal codes. It sought to provide France with a single system of law where there were two: customary law in the north, and Roman law in the south.

One of Louis's more infamous decrees was the Grande Ordonnance sur les Colonies of 1685, also known as Code Noir. It granted sanction to slavery, although it did extend a measure of humanity to the practice by prohibiting the separation of families. However, no person could own a slave in the French colonies unless he were a member of the Roman Catholic Church, and a Catholic priest had to baptise each slave.

[edit] Patronage of the arts

The Sun King proved a generous spender, dispensing large sums of money to finance the royal court, and supported those who worked under him. He brought the Académie Française under his patronage, and became its "Protector". It was under his reign and indeed his patronage that Classical French literature flourished with such writers as Molière, Jean Racine and Jean de La Fontaine whose works still hold great influence to this day. The visual arts also found in Louis XIV their patron for he funded and commissioned various artists, such as Charles Le Brun, Pierre Mignard, Antoine Coysevox and Hyacinthe Rigaud whose works became famed throughout Europe. In music, composers and musicians like Jean-Baptiste Lully, Jacques Champion de Chambonnières and François Couperin thrived and influenced many others.

Louis ordered the construction of the military complex known as the "Hôtel des Invalides" to provide a home for the officers and soldiers who had served him loyally in the army, but who had been rendered infirm by either injury or age. While the practice of pharmacy was still quite elementary, les Invalides pioneered new treatments and set new standards for hospice treatment.

He also improved the Louvre, as well as many other royal residences. Originally, when planning additions to the Louvre, Louis XIV had hired Gian Lorenzo Bernini as architect. However, his plans for the Louvre would have called for the destruction of much of the existing structure, replacing it with an Italian summer villa in the centre of Paris.

In June 1686, on the instruction of his secret wife, Madame de Maintenon, he signed the letters patent creating the Institut de Saint-Louis at Saint-Cyr for filles pauvres de la noblesse (poor noble girls) between the ages of seven and twenty.[9] Construction had begun two years previously. "Saint-Cyr" was at the time the only educational institution for girls in France that was not a convent. The 250 demoiselles admitted were required to provide documentary evidence of at least four generations of nobility on their father's side.[9] Mme de Maintenon took great pleasure in this school and was finally to die there.[9]

| Royal styles of King Louis XIV Par la grâce de Dieu, Roi de France et de Navarre |

|

| Reference style | His Most Christian Majesty |

|---|---|

| Spoken style | Your Most Christian Majesty |

| Alternative style | Monsieur Le Roi |

[edit] Early wars in the Low Countries

| This section may need to be rewritten entirely to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as Edit for stylistic continuity; correction of grammatical and syntactical errors. You can help. The discussion page may contain suggestions. (August 2008) |

After Louis XIV's father-in-law and uncle, Philip IV of Spain, died in 1665, Philip IV's son (by his second wife) became Charles II of Spain. Louis XIV claimed that Brabant, a territory in the Low Countries ruled by the King of Spain, had "devolved" to his wife, Marie-Thérèse, Charles II's elder half-sister by their father's first marriage.

Problems internal to the Republic of the Seven United Provinces (the Netherlands) aided Louis XIV's designs on the Low Countries. The most prominent political figure in the United Provinces at the time, Johan de Witt, Grand Pensionary, feared the ambition of the young William III, Prince of Orange, who in seeking to seize control might thus deprive De Witt of supreme power in the Republic and restore the House of Orange to the influence it had hitherto enjoyed until the death of William II, Prince of Orange.

Shocked by the rapidity of French successes and fearful of the future, the United Provinces turned on their former friends and put aside their differences with England and, when joined by Sweden, formed a Triple Alliance in 1668. Faced with the threat of escalation and having signed a secret treaty partitioning the Spanish succession with the Emperor, the other major claimant, Louis XIV agreed to make peace.

The Triple Alliance did not last very long. In 1670, Charles II of England, lured by French bribes and pensions, signed the secret Treaty of Dover, entering into an alliance with France; the two kingdoms, along with certain Rhineland German princes, declared war on the United Provinces in 1672, sparking off the Franco-Dutch War. The rapid invasion and occupation of most of the Netherlands precipitated a coup, which toppled De Witt and allowed William III to seize power. William III entered into an alliance with Spain, the Emperor and the rest of the Empire; and a treaty of peace with England was signed in 1674, the result of which was England's withdrawal from the war and the marriage between William III and Lady Mary, niece of the English King Charles II.

Despite these diplomatic and military reverses, the war continued with brilliant French victories against the overwhelming forces of the opposing coalition. In a matter of weeks in 1674, the Spanish territory of Franche-Comté fell to the French armies under the eyes of the king; while Condé defeated a much larger combined army, with Austrian, Spanish and Dutch contingents, under the Prince of Orange, at the Battle of Seneffe, preventing them from descending on Paris. In the winter of 1674–1675, the outnumbered Turenne, through a most daring and brilliant campaign, inflicted defeat upon the Imperial armies under Raimondo Montecuccoli, drove them out of Alsace and back across the Rhine, and recovered the province for Louis XIV. Through a series of feints, marches and counter-marches towards the end of the war, Louis XIV led his army to besiege and capture Ghent, an action which dissuaded Charles II and his English Parliament from declaring war on France and which allowed Louis, in a very superior position, to force the allies to the negotiating table. After six years, Europe was exhausted by war, and peace negotiations commenced, being accomplished in 1678 with the Treaty of Nijmegen. While Louis XIV returned all captured Dutch territory, he gained more towns and associated lands in the Spanish Netherlands and retained Franche-Comté, which had been captured by Louis and his army in a matter of weeks.

The Treaty of Nijmegen further increased France's influence in Europe, but did not satisfy Louis XIV. The King dismissed his foreign minister Simon Arnauld, marquis de Pomponne in 1679, viewed as timorous and as having compromised too much with the allies. Louis XIV also kept up his army but, instead of pursuing his claims through purely military action, utilised judicial processes to accomplish further territorial aggrandizement. Thanks to the ambiguous nature of treaties of the time, Louis was able to claim that the territories ceded to him in previous treaties ought to be ceded along with all their dependencies and lands which had formerly belonged to them, as had in fact been stipulated in the peace treaties, but had separated over the years.

Louis sought to gain cities and territories such as Luxembourg, for its strategic offensive and defensive position on the frontier, as well as Casale, which would give him access to the Po river valley in the heart of Northern Italy. Louis also desired to gain Strasbourg, an important strategic outpost through which various Imperial armies had in the previous wars crossed over the Rhine to invade France. Strasbourg was a part of Alsace, but had not been ceded with the rest of Habsburg-ruled Alsace in the Peace of Westphalia.

[edit] Height of power

By the early 1680s, Louis XIV had greatly augmented his and France's influence and power in Europe and the world.

[edit] Foreign affairs

In the sphere of foreign affairs outside Europe, French colonies were multiplying in the Americas, Asia and Africa, while diplomatic relations had been initiated with countries as far afield as Siam (through the embassy of Chaumont), India and Persia. An Ottoman Empire embassy arrived in 1669 led by Suleiman Aga, reviving an ancient Franco-Ottoman alliance.[10] The explorer René Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle claimed and named, in 1682, the basin of the Mississippi River in North America, "Louisiane", in honour of Louis XIV, while French Jesuits and missionaries could be seen at the court of the Manchu Emperor Kangxi in China. In France, Louis XIV received the visit of a Chinese Jesuit named Michael Shen Fu-Tsung as early as 1684,[11] and a few years later he had a Chinese librarian and translator at his court, named Arcadio Huang.[12][13] A Persian embassy to Louis XIV occured in 1715, the year of the king's death.

[edit] Domestic affairs

Domestically, Louis succeeded in establishing and increasing the influence and central authority of the crown at the expense of the church and aristocracy. He sought to reinforce traditional Gallicanism, a doctrine limiting the authority of the Pope in France, and convened an assembly of clergymen (the Assemblée du Clergé) in November 1681. Before it was dissolved in June 1682, it had agreed to the Declaration of the Clergy of France. The power of the King of France was increased in contrast to the power of the Pope, which was reduced. Bishops were not to leave France without royal approval; no government officials could be excommunicated for acts committed in pursuance of their duties; and no appeal could be made to the Pope without the approval of the king. The king was allowed to enact ecclesiastical laws, and all regulations made by the Pope were deemed invalid in France without the assent of the monarch. The Declaration was not accepted by the Pope, which is not surprising given the infringements of the document upon papal authority.[1]

Louis also achieved immense control over the nobility in France by attaching much of the higher nobility to his orbit at his palace at Versailles. He expected them to spend the majority of the year under his close watch instead of on their own estates and in their regional power-bases, where historically nobles waged local wars with neighbors or plotted resistance to royal authority. Only by being in constant attendance upon him were they able to gain the pensions and privileges necessary to lead lives considered appropriate to their rank. Louis entertained his permanent visitors with extravagant luxury and other distractions which helped him awe and domesticate his hitherto unruly nobility.

As a result of the Fronde, Louis believed that his power would prevail only if he filled high executive offices with commoners, or at least members of the relatively newer bureaucratic aristocracy (the noblesse de robe), because, he believed, while he could reduce a commoner to a nonentity by simply dismissing him, he could not destroy the entrenched influence of a great nobleman of ancient lineage as easily. Thus Louis half-forced, half-seduced the noblesse d'épée into serving him ceremonially as courtiers, whilst he appointed commoners or newer nobles as ministers and regional intendants. As courtiers, the power of the great nobles grew ever weaker.

In fact, the victory of the Crown over the nobles, finally achieved under Louis XIV, ensured that the Fronde was the last major civil war to plague France until the Revolution and the Napoleonic Age. Indeed, John A. Lynn has calculated that after Louis XIV there was a significant drop in years with internal civil war. The number of years dropped from a high of around 50 years out of 101 between 1560 and 1660 (50%), to six years out of 55 during Louis' personal reign from 1661 to 1715 (11%), to no civil wars till the Revolution in 1789.[14] Not until the Revolution, about a hundred years later, did civil war once again trouble France.

Louis XIV had the Palace of Versailles, originally a hunting lodge built by his father, converted into a spectacular royal palace in a series of four major and distinct building campaigns. By the end of the third building campaign, the château had taken on most of the appearance that it retains to this day, except for the current chapel built in the last decade of the reign. He officially moved there, along with the royal court, on 6 May 1682. Louis had several reasons for creating such a symbol of extravagant opulence and stately grandeur, and for shifting the seat of the monarchy. The assertion that he did so because he hated Paris, however, is flawed as he did not cease to embellish his capital with glorious monuments while improving and developing it. On the other hand, contemporary writers such as Saint-Simon speculated that Louis viewed Versailles as an isolated power center where treasonous cabals could be more readily recognized.[15]

Versailles served as a dazzling and awe-inspiring setting for state affairs and for the reception of foreign dignitaries, where the attention was not shared with the capital and the people, but was assumed solely by the person of the king. Thus, many noblemen had perforce either to give up the cachet and opportunites associated with sharing in the king's company, or to depend entirely on the king for the grants and subsidies necessary to do so in proper style.[15] Instead of exercising power and potentially creating trouble, the nobles vied for the honour of dining at the king's table or the privilege of carrying a candlestick as the king retired to his bedroom.

Reparation faite à Louis XIV par le Doge de Gênes.15 mai 1685 by Claude Guy Halle, Château de Versailles

By 1685, Louis stood at the apogee of his power. One of France's chief rivals, the Holy Roman Empire, was occupied in fighting the Ottoman Empire in the Great Turkish War, which had begun in 1683 would last sixteen years. The Ottoman Grand Vizier had almost captured Vienna, but at the last moment John III Sobieski, King of Poland led an army of Polish and Imperial forces to victory at the Battle of Vienna in 1683. In the meantime, by the Truce of Ratisbon signed on 15 August 1684, Louis XIV had acquired control of several territories which covered the frontier and protected France from foreign invasion. After repelling the Ottoman attack on Vienna, the Emperor was no longer in imminent danger from the Turks, nevertheless he did not attempt to regain the territories annexed by Louis.

Louis's queen, Marie-Thérèse (Maria Theresa of Spain), died in 1683. He remarked on her demise that on no other occasion had she ever caused him unease. Although he was said to have performed his marital duties nightly, he had not remained faithful to her for long after their union in 1660: his mistresses included Louise de la Vallière, duchesse de Vaujours; Françoise-Athénaïs de Rochechouart-Mortemart, marquise de Montespan; and Marie-Angélique de Scoraille, duchesse de Fontanges. As a result, he produced many illegitimate children, most of whom were joined in marriage with members of cadet branches of the royal family itself.

He proved, however, more faithful to his second wife, Françoise d'Aubigné, marquise de Maintenon. The secret marriage between Louis XIV and Madame de Maintenon - the nuptial mass probably occurred at midnight on 10 October 1683 in a chapel at Versailles[9] - was an "open secret" as it was generally known but was never discussed or announced publicly, and would last to his death. The marriage is sometimes described as an morganatic marriage but this is incorrect as morganatic marriages are not defined under French Law.[16]

[edit] Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

Madame de Maintenon, once a Protestant, had herself converted to Roman Catholicism in her youth under some duress. It was once believed that she vigorously promoted the persecution of the Protestants, and that she urged Louis XIV to revoke the Edict of Nantes (1598), which granted a degree of religious freedom to the Huguenots. However, this view of her participation is now being questioned.[17] It has been suggested that Marie-Thérèse, on her deathbed, had urged Louis on the subject, which, given her Spanish Catholic upbringing, is not surprising. Whatever the truth of such a proposition, Louis XIV himself clearly supported such a plan; he believed, along with the rest of Europe, Catholic or Protestant, that, in order to achieve national unity, he had to first achieve a religiously unified nation—specifically a Catholic one in his case. This was enshrined in the principle of "cuius regio, eius religio" ("whose realm, his religion"), which defined religious policy throughout Europe since its establishment, by the Peace of Augsburg, in 1555. He had already begun the persecution of the Huguenots by quartering soldiers in their homes, though it must be said that it was theoretically within his feudal rights, and hence legal, to do so with any of his subjects.

Louis continued his attempt to achieve a religiously united France by issuing an edict, in March 1685, which affected the French colonies, and expelled all Jews from them. The public practice of any religion except Roman Catholicism became prohibited. In October 1685, Louis XIV issued the Edict of Fontainebleau, revoking that of Nantes, on the pretext that the near-extinction of Protestantism and Protestants in France made any edict granting them privileges redundant.[1] The Edict decreed that "liberty is granted to the said persons of the Pretended Reformed Religion Protestantism ... on condition of not engaging in the exercise of the said religion, or of meeting under pretext of prayers or religious services." Thus, it precluded individuals from publicly practising or exercising the religion, but not from merely believing in it. It banished from the realm any Protestant minister who refused to convert to Roman Catholicism. Protestant schools and institutions were banned. Children born into Protestant families were to be forcibly baptised by Roman Catholic priests, and Protestant places of worship were demolished.

Although the Edict formally denied Huguenots permission to leave France, about 200,000 of them left in any case, taking with them their skills in commerce and trade. The Edict proved economically damaging to France,[18] though not ruinous; and while Vauban, one of Louis XIV's most influential generals, publicly condemned the measure, its proclamation was celebrated by many Catholics throughout the realm.

[edit] The League of Augsburg

| This section may need to be rewritten entirely to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as The detail of this section is beyond the scope this article; the article is about Louis XIV, not the War of the League of Augsburg. You can help. The discussion page may contain suggestions. (August 2008) |

[edit] Causes and conduct of the war

The wider political and diplomatic result of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, however, was to provoke increased anti-French sentiment in Protestant countries. In 1686, both Catholic and Protestant rulers joined in the League of Augsburg, ostensibly a defensive pact to protect the Rhine, but really designed as an offensive alliance against France. The coalition included the Holy Roman Emperor and several of the German states that formed part of the Empire – most notably the Palatinate, Bavaria, and Brandenburg. The United Provinces, Spain and Sweden also adhered to the League.[citation needed]

In 1685, Charles II, Elector Palatine, the brother of Louis XIV's sister-in-law, Elizabeth Charlotte, "Liselotte", duchesse d'Orléans, had died. The palatine crown had gone, not to her, but to the junior Neuburg branch of the family. Louis had sought, through an ultimatum to the German princes, to have his sister-in-law's claims recognised. However, the expiry of this ultimatum and another to the German princes to ratify the Truce of Ratisbon and confirm Louis' possession of annexed territories, along with disputes over the succession to the Electorate of Cologne, led to his sending troops into the Palatinate in 1688. Ostensibly, the army had the task of supporting the claims of Liselotte to the Palatinate. The real aim, however, of the invasion was to apply pressure and force the Palatinate to leave, and thus weaken, the League of Augsburg. The troops under the command of Melac eventually executed Louis' order "Brûlez le Palatinat!" ("Burn the Palatinate!") and devastated large areas of South Western Germany. This scorched earth policy aimed at preventing the larger gathering Imperial army from reaching the frontiers of France and invading Lorraine and Alsace.[citation needed]

Louis XIV's actions united the German princes behind the Holy Roman Emperor. Louis had expected that England, under the Catholic James II, would remain neutral. In 1688, however, the "Glorious Revolution" resulted in the deposition of James II and his replacement by his daughter, Mary II, who ruled jointly with her husband, William III, now King of England. As William III had developed an enmity against Louis XIV during the Franco-Dutch War, he pushed England into the League of Augsburg, which then became known as the Grand Alliance.[citation needed]

The campaigns of the War of the Grand Alliance (1688–1697) generally proceeded favorably for France. The forces of the Holy Roman Emperor proved ineffective, as many Imperial troops were still occupied in the Balkans with the Great Turkish War, and because the Imperials generally took to the field much later than the French. Thus, France could accumulate a string of victories from Flanders in the north, to the Rhine valley in the east, to Italy and Spain in the south, as well as on the high seas and in the colonies.[citation needed]

Louis XIV aided James II in his attempt to regain the British crown, but the Stuart king was unsuccessful and was defeated at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. A year later, the last Jacobite stronghold, Limerick, fell to Williamite forces after the Battle of Aughrim, and James' dreams of returning to the throne dissipated. Williamite England could then devote more of her funds and troops to the war on the Continent.[citation needed]

Nonetheless, despite the size of the opposing coalition, which encompassed most of Europe, French forces in Flanders under the famous pupil of Condé, François Henri de Montmorency-Bouteville, duc de Luxembourg, nicknamed "le tapissier de Notre-Dame" for the number of captured enemy standards which he sent to decorate the Cathedral, crushed the allied armies at the Battle of Fleurus in the same year as the Battle of the Boyne, as well as at the Battle of Steenkerque two years later and the Battle of Landen a year after that.

Under the personal supervision of Louis XIV, the French army captured Mons in 1691 and the hitherto impregnable fortress of Namur in 1692; and with the capture of Charleroi by Luxembourg in 1693 after his victory at Landen, France gained the forward defensive line of the Sambre. At the Battles of Marsaglia and of Staffarde, France was victorious over the allied forces under Victor Amadeus, Duke of Savoy, overrunning his dominion and reducing the territory under his effective command to merely the area around Turin. In the southeast, along the Pyrenees, the Battle of Torroella opened Catalonia to French invasion. The French naval victory at the Battle of Beachy Head in 1690, however, was offset by the Anglo-Dutch naval victory at the Battles of Barfleur and La Hougue in 1692; but neither side was able to entirely defeat the opposing navy.[citation needed]

The war continued for four more years, until the Duke of Savoy signed a separate peace and subsequent alliance with France in 1696, the Treaty of Turin, undertaking to join with French arms in a capture of the Milanese and allowing French armies in Italy to reinforce others; one of these reinforced armies, that of Spain, captured Barcelona and hastened the arrival of peace.[citation needed]

[edit] Treaty of Ryswick

The War of the Grand Alliance eventually ended with the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697. Louis XIV surrendered Luxembourg and most of the other Réunion territories he had seized since the end of the Dutch War in 1679, but retained Strasbourg, assuring the Rhine as the border between France and the Empire. He also gained de jure recognition of his hitherto de facto possession of Saint-Domingue, as well as the return of Pondicherry and Acadia. Louis undertook to recognise William III and Mary II as joint sovereigns of Great Britain and Ireland, and assured them that he would no longer assist James II; at the same time he renounced intervention in the Electorate of Cologne and claims to the Palatinate, in return for financial compensation. Louis XIV returned Lorraine to her duke, but on terms which allowed French passage at any time and which severely restricted his political maneuverability. The Dutch were allowed to garrison forts in the Spanish Netherlands, the "Barrier", to protect themselves against possible French aggression. Spain recovered Catalonia and the many territories lost, both in this war and the previous one (War of the Reunions), in the Low Countries.[citation needed]

Of similar note, Louis secured the dissolution of they Grand Alliance by manipulating the rivalries and suspicions of its member states; in so doing, he divided his enemies and broke their power since no single state on its own was capable of taking on France. The generous terms of the treaty were seen as concessions to Spain designed to foster pro-French sentiment, which would eventually lead Charles II, King of Spain to declare as his heir, Louis' grandson Philippe, duc d'Anjou. Moreover, despite such seemingly disadvantageous terms in the Treaty of Ryswick, French influence was still at such a height in all of Europe that Louis XIV could offer his cousin, François Louis de Bourbon, prince de Conti, the Polish crown, duly have him elected by the Sejm and proclaimed as King of Poland by the Polish primate. However, Conti's own tardiness in proceeding to Poland to claim the throne allowed a rival, Augustus II the Strong, Elector of Saxony to have himself crowned king instead.[citation needed]

[edit] War of the Spanish Succession

| This section may need to be rewritten entirely to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as The detail of this section is beyond the scope this article; the article is about Louis XIV, not the War of the Spanish Succession. You can help. The discussion page may contain suggestions. (August 2008) |

[edit] Causes and build-up to the war

The great matter of the succession to the Spanish throne dominated European foreign affairs following the Peace of Ryswick. The Spanish King Charles II, severely incapacitated, could not father an heir. The Spanish inheritance offered a much sought-after prize, for Charles II ruled not only Spain, but also Naples, Sicily, the Milanese, the Spanish Netherlands and a vast colonial empire—in all, twenty-two different realms and dominions, many of which were on the periphery of France.[citation needed]

France and Austria were the main claimants to the throne, both of which had close family ties to the Spanish royal family. Anjou (later Philip V of Spain), the French claimant, was the great-grandson of the eldest daughter of Philip III of Spain, Anne of Austria, and the grandson of the eldest daughter of Philip IV of Spain, Marie-Thérèse. The only bar to inheritance lay in their renunciations of claims to the throne, which in the case of Marie-Thérèse, however, was considered legally null and void as other terms of the marriage treaty had not been fulfilled by Spain.[citation needed]

Charles, Archduke of Austria (later Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor) and younger son of Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor by his third marriage (with Eleonore-Magdalena of Neuburg), claimed the throne through his paternal grandmother, Maria Anna of Spain, who was the youngest daughter of Philip III; this claim was not, however, tainted by any renunciation. Purely on the basis of the laws of primogeniture, however, France had the best claims since they were derived from the eldest daughters in each generation.[citation needed]

Many European powers feared that if either France or the Emperor came to control Spain, the balance of power in Europe would be threatened. Thus, both the Dutch and the English preferred another candidate, the Bavarian prince Joseph Ferdinand, who was the grandson of Leopold I, through his first wife Margaret Theresa of Spain, younger daughter of Philip IV. Under the terms of the First Partition Treaty, it was agreed that the Bavarian prince would inherit Spain, with the territories in Italy and the Low Countries being divided between the Houses of France and Austria. Spain, however, had not been consulted, and vehemently resisted the dismemberment of its empire. The Spanish court insisted that their empire was indivisible. When the Treaty became known to Charles II in 1698, he settled on Joseph Ferdinand as his sole heir, assigning to him the entire Spanish inheritance.[citation needed]

The issue opened up again when smallpox claimed the Bavarian prince six months later. The Spanish court, seeking to keep the inheritance undivided, acknowledged that they could only succeed in doing so by granting the crown to a member from either the House of France, or of Austria. Charles II, under pressure from his German wife Maria Anna of Neuburg, chose the House of Austria and her nephew, settling on the Emperor's younger son, the Archduke Charles. Ignoring this, Louis and William III signed a second treaty, that of London, allowing the Archduke Charles to take Spain, the Low Countries and the Spanish colonies, whilst Louis XIV's eldest son and heir, le Grand Dauphin, would inherit the territories in Italy, with a mind to exchange them for Savoy or Lorraine.[citation needed]

[edit] Acceptance of the will and consequences

| This section may need to be rewritten entirely to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as Need for links to Wikipedia articles. You can help. The discussion page may contain suggestions. (August 2008) |

In 1700, as he lay upon his deathbed, Charles II unexpectedly interfered in the affair. He sought to prevent Spain from uniting with either France or the Empire, but, based on his past experience of French superiority in arms, considered France as more capable of preserving his empire in its entirety. The whole of the Spanish inheritance was thus offered to Anjou, the Dauphin's second son, on condition he kept it undivided. In the event of his refusal or inability to accept the inheritance, it would be offered to the Dauphin's youngest son, Charles, duc de Berry, and thereafter to the Archduke Charles.[19] If all these princes refused the Crown, it would be offered to the House of Savoy, distantly related to the Spanish Royal Family.[citation needed]

Louis XIV thus faced a difficult choice: he could have agreed to a partition and to possible peace in Europe, or he could have accepted the whole Spanish inheritance but alienated the other European nations. Louis originally assured William III that he would fulfill the terms of their previous treaty and partition the Spanish dominions. However, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, marquis de Torcy, the nephew of Colbert, advised Louis that even if France accepted a portion of the Spanish inheritance, a war with the Empire would almost certainly ensue; and William III had made it very clear that he had signed the Partition Treaties to avoid war, not make it, and hence would not assist France in a war to obtain the territories granted her by those treaties. Louis agreed that if a war had to occur, it would be more profitable to accept the whole of the Spanish inheritance and to fight a defensive war. Consequently, when Charles II died on 1 November 1700, Philippe, duc d'Anjou became Philip V, King of Spain.[citation needed]

Most of the rest of Europe accepted Philip V as King of Spain, albeit reluctantly. Louis, however, acted too precipitously. In 1701, he transferred the Asiento, a permit to sell slaves to the Spanish colonies, to France, with potentially damaging consequences for British trade. Moreover, Louis ceased to acknowledge William III as King of Great Britain and Ireland upon the death of James II, instead acclaiming as King James II's son, James Francis Edward Stuart (the "Old Pretender"). Furthermore, Louis sent forces into the Spanish Netherlands to secure its loyalty to Philip V and to garrison the Spanish forts, which had been garrisoned by Dutch troops as part of the "Barrier" protecting the United Provinces from potential French aggression. The result was the further alienation of both Britain and the United Provinces, both then ruled by William III. Consequently, another Grand Alliance was formed between Great Britain, the United Provinces, the Emperor and many of the petty states within the Holy Roman Empire. French diplomacy, however, secured Bavaria, Portugal and Savoy as allies for Louis and Philip.[citation needed]

[edit] Commencement of fighting

The subsequent War of the Spanish Succession continued for most of the remainder of the reign and proved costly for Louis. It began with Imperial aggression in Italy even before war was officially declared. France had some initial success, nearly capturing Vienna, but the victories of Marlborough and Eugene of Savoy showed that the myth of French invincibility was broken.[citation needed]

[edit] End of French invincibility

Following Marlborough and Eugene of Savoy's victory at the Battle of Blenheim, Bavaria was flung out of the war, being partitioned between the Palatinate and Austria, and her elector, Maximilian II Emanuel, forced to flee to the Spanish Netherlands. Another consequence of Blenheim was the subsequent defection of Portugal and Savoy to the opposing side. With the Battle of Ramillies and that of Oudenarde, Franco-Spanish forces were driven ignominiously out of the Spanish Netherlands; while the Battle of Turin forced Louis to evacuate what few forces remained to him in Italy.[citation needed]

Such military defeats, coupled with famine and mounting debt, forced France into a defensive posture. By 1709, Louis' position was grievously weakened, and he was willing to sue for peace at nearly any cost, even to return all lands and territories ceded to him during his reign and to return to the frontiers of the Peace of Westphalia, signed more than sixty years prior. Nonetheless, the terms dictated by the allies were so harsh, including demands that he attack his own grandson alone to force the latter to accept the humiliating peace terms, that war continued.[citation needed]

[edit] Turning point

Whilst it became clear that France could not retain the entire Spanish inheritance, it also seemed evident that its opponents could not overthrow Philip V in Spain after the definitive Franco-Spanish victory of the Battle of Almansa, and those of Villaviciosa and Brihuega, which drove the allies out of the central Spanish provinces. Furthermore, the Battle of Malplaquet in 1709 showed that it was neither easy nor cheap to defeat and invade France, for while the allies gained the field, they did so at an abominable cost, losing 25 000 men, twice that of the French, led by their capable general, the duc de Villars. The Battle of Denain in 1712 turned the war in favour of Louis XIV, when Villars led French forces to a decisive victory over the allies under Eugene of Savoy, recovering much lost territory and pride.[citation needed]

The death of Joseph I, Holy Roman Emperor, who had succeeded his father Leopold I in 1705, made the prospect of an empire as large as that of Charles V being ruled by the Archduke Charles, now the Emperor, dangerously possible. This was, to Great Britain, as undesirable as a union of France and Spain.[citation needed]

[edit] Road to and conclusion of peace

Thus, preliminaries were signed between Great Britain and France in the pursuit of peace. Louis XIV and Philip V eventually made peace with Great Britain and the United Provinces in 1713 with the Treaty of Utrecht. Peace with the Emperor and the Holy Roman Empire came with the Treaty of Rastatt and that of Baden in 1714 respectively. The crucial interval between Utrecht and Rastatt-Baden allowed Louis XIV to capture Landau and Freiburg, permitting him to negotiate from a comparatively better position, if not from one of strength, with the Emperor and the Empire.[citation needed]

The general settlement recognised Philip V as King of Spain and ruler of the Spanish colonies. Spain's territory in the Low Countries and Italy were partitioned between Austria and Savoy, while Gibraltar and Minorca were retained by Great Britain.[citation needed]

Louis XIV, furthermore, agreed to end his support for the Old Pretender's claims to the throne of Great Britain. France was also obliged to cede the colonies and possessions of Newfoundland, Rupert's Land and Acadia in the Americas to Great Britain, while retaining Île-Saint-Jean (now Prince Edward Island) and Île Royale (now Cape Breton Island); however, most of those Continental territories lost in the devastating defeats in the Low Countries were returned to her, despite allied persistence and pressure to the contrary, and she also received further territories to which she had a claim such as the Principality of Orange, as well as the Ubaye Valley, which covered the passes through the Alps from Italy.[citation needed]

The efforts of the allies to curb and diminish French power in Europe came to naught. Moreover, France was shown to be able to protect her allies with the rehabilitation and restoration of the Elector of Bavaria, Maximilian II Emanuel, to his lands, titles and dignities.[citation needed]

[edit] Death

| This section may need to be rewritten entirely to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as Edit to correct grammatical and syntactical errors; addition of Wiki links. You can help. The discussion page may contain suggestions. (August 2008) |

Louis XIV died on 1 September 1715, of gangrene, a few days before his seventy-seventh birthday. Almost all of Louis XIV's legitimate children had died during childhood. The only one to survive to adulthood, his eldest son, Louis de France, known as "Le Grand Dauphin", had predeceased Louis XIV in 1711, leaving three children. The eldest of these children, Louis, duc de Bourgogne, had died in 1712, soon to be followed by Bourgogne's elder son, Louis, duc de Bretagne. Thus, at Louis XIV's death, his five-year-old great-grandson Louis, duc d'Anjou, the youngest son of Bourgogne, and the Dauphin upon the death of his grandfather, father and elder brother, succeeded to the throne as Louis XV.

It was to this young child that Louis XIV was alleged, according to Philippe de Courcillon, marquis de Dangeau in his Memoirs, to have said, in the manner of baroque piety:

"Do not follow the bad example which I have set you; I have often undertaken war too lightly and have sustained it for vanity. Do not imitate me, but be a peaceful prince, and may you apply yourself principally to the alleviation of the burdens of your subjects".

This same Dangeau noted of his death that "he yielded up his soul without any effort, like a candle extinguishing". Louis died while saying the words of the psalm Domine, ad adjuvandum me festina (O Lord, make haste to help me).[citation needed]

Louis XIV, noting his own old age and the youth of his heir, had anticipated a regency and had sought to restrict the power of his nephew, Philippe II, duc d'Orléans, who as closest surviving legitimate relative in France would become Regent for the prospective Louis XV. Thus, he transferred some power to his illegitimate son by Madame de Montespan, Louis-Auguste de Bourbon, duc du Maine and created a regency council like that established by Louis XIII in anticipation of Louis XIV's own minority.[citation needed]

Louis XIV's will provided that Maine would act as the guardian of Louis XV, superintendent of the young king's education and Commander of the Royal Guards.[citation needed]

Orléans, however, obtained the annulment of Louis XIV's will in the Parlement de Paris after the latter's death. Maine was stripped of the rank of "prince du sang", which had been given him and his brother, Louis-Alexandre de Bourbon, comte de Toulouse, by Louis, and of the command of the Royal Guards, but retained his position as superintendent, while Orléans was to rule as sole Regent. Toulouse, by remaining aloof from these court intrigues, managed to retain his privileges (save that of "prince du sang"), unlike his brother.[citation needed]

Louis XIV's body lies in the Saint Denis Basilica in Saint Denis, a suburb of Paris. He reigned for 72 years, making his the longest reign in the recorded history of Europe.

[edit] Legacy

| This section may need to be rewritten entirely to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as Edit to cleanup grammatical and syntactical errors; addition of Wiki links. You can help. The discussion page may contain suggestions. (August 2008) |

A member of the House of France was placed on the throne of Spain by Louis XIV, effectively ending the centuries-old threat and menace that had arisen from that quarter of Europe since the days of Charles V. The House of Bourbon retained the crown of Spain for the remainder of the eighteenth century, but experienced overthrow and restoration several times after 1808. Nonetheless, to this day, the Spanish monarch is descended from Louis XIV.

Louis' numerous wars effectively bankrupted the State (though it must also be said that France was able to recover in a matter of years), forcing him to incur large State debts from various financiers and to levy higher taxes on the peasants as the nobility and clergy had exemption from paying these taxes and contributing to public funds. Yet, it must be emphasized that it was the State, and not the country, which was impoverished. The wealth and prosperity of France, as a whole, could be noted in the writings of the social and political thinker and commentator Montesquieu in his satirical epistolary novel, Lettres Persanes. While the work mocks and ridicules French political, cultural and social life, it also portrays and describes the wealth, elegance and opulence of France between the end of the War of the Spanish Succession and Louis XIV's death.[citation needed]

On the whole, nevertheless, Louis XIV strengthened the power of the Crown relative to the traditional feudal elites, marking the beginning of the era of the modern State, and placed France in the predominant and preeminent position in Europe, giving her ten new provinces and an overseas empire, as well as cultural and linguistic influence all over Europe. Even with several great European alliances opposing him, he continued to triumph and to increase French territory, power and influence. As a result of these military victories as well as cultural accomplishments, Europe would admire France, her power, culture, exports, values and way-of-life. The French language would become the lingua franca for the entire European elite as faraway as Romanov Russia; various German princelings would seek to copy his mode of life to their great expense. Europe of the Enlightenment would look to Louis XIV's reign as an example, studying his strategic use of power, emulating his elegance, and admiring his successes.[citation needed]

Saint-Simon, who felt slighted by Louis XIV, offered the following assessment:

"There was nothing he liked so much as flattery, or, to put it more plainly, adulation; the coarser and clumsier it was, the more he relished it ... His vanity, which was perpetually nourished–for even preachers used to praise him to his face from the pulpit–was the cause of the aggrandisement of his Ministers".

However, even the German philosopher Leibniz, who was a Protestant and had no cause for flattery, could call him "one of the greatest kings that ever was"; and Napoleon, hardly a friend of the Bourbons, would describe Louis XIV as "the only King of France worthy of the name" and "a great king."[20] Voltaire, the apostle of the Enlightenment, compared him to Augustus and called his reign an "eternally memorable age", dubbing the Age of Louis XIV "le Grand Siècle" (the "Great Century"). He is also regarded as one of the greatest rulers in the 17th century alongside with Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Empire and Peter I of Tzarist Russia.[citation needed]

[edit] Style and arms

Louis XIV had the formal style: "Louis XIV, par la grâce de Dieu, roi de France et de Navarre", or "Louis XIV, by the Grace of God, King of France and of Navarre". He bore the arms Azure three fleurs-de-lis Or (for France) impaling Gules on a chain in cross saltire and orle Or an emerald Proper (for Navarre).[citation needed]

[edit] Order of Saint Louis

The Royal and Military Order of Saint Louis (French: Ordre Royal et Militaire de Saint-Louis) was a military Order of Chivalry founded on 5 April 1693 by Louis XIV[21][22] and named after Louis IX. It was intended as a reward for outstanding officers, and is notable as the first decoration that could be granted to non-nobles. It is roughly the forerunner of the Légion d'honneur, with which it shares the red ribbon (though the Légion d'honneur is awarded to military personnel and civilians alike).

[edit] Ancestors

[edit] Issue

[edit] In fiction

Louis XIV is depicted in two of Alexandre Dumas' novels, first as a child in Twenty Years After, then as a young man in The Vicomte de Bragelonne, in which he is a central character. French academic Jean-Yves Tadié has argued that the beginning of Louis XIV's personal rule is the latter novel's real subject.[23]

Most film versions of the Man in the Iron Mask's story are based on the legend that the mysterious prisoner was actually Louis XIV's twin brother. This legend is also depicted in Dumas' novel, on which most film versions are loosely based.

In 1910 the American historical novelist Charles Major wrote "The Little King: A Story of the Childhood of King Louis XIV".

King Louis XIV is a major character in the 1959 historical novel "Angélique et le Roy" ("Angélique and the King"), part of the Angelique Series. The book's main character, a strong-willed lady at the court in Versailles, rejects the King's advances and refuses to become his mistress. The dire consqences of her defying this powerful monarch are depicted in a later book, the 1961 "Angélique se révolte" ("Angélique in Revolt").

A character based on Louis XIV plays an important role in The Age of Unreason, a series of four alternate history novels written by American science fiction and fantasy author Gregory Keyes.

The Taking of Power by Louis XIV directed by Roberto Rossellini in 1966 show Louis rise to power after the death of Cardinal Mazarin. Released on DVD January 2009.

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b c "Louis XIV". Catholic Encyclopedia. 2007. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09371a.htm. Retrieved on 2008-01-19.

- ^ "Louis XIV". MSN Encarta. 2008. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761572792/Louis_XIV.html. Retrieved on 2008-01-20.

- ^ (French) Marquis de Dangeau. "Mémoire sur la mort de Louis XIV (on page 24)". http://gallica.bnf.fr/Catalogue/noticesInd/FRBNF30298192.htm. Retrieved on 2007-10-05.

- ^ François Bluche (translated by Mark Greengrass (1990). Louis XIV. New York: Franklin Watts. p. 11.

- ^ (French) Bremond, Henri. La Provence mystique au XVIIe siècle. Paris: Plon-Nourrit, 1908. pp. 381, 382.

- ^ (French) Laurentin, René. Le Vœu de Louis XIII. Paris: FX de Guibert, 1988. pp. 62, 63.

- ^ (French) 5 September 1638 - The birth of the future "Sun King" and This happened on ... 15 August - The feast of Assumption, the website Herodote.net. Retrieved on 2008-02-19;

"Louis XIV". MSN Encata. 2008. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761572792/Louis_XIV.html. Retrieved on 2008-01-20. - ^ Genealogist C. Carretier calculated Louis XIV's ancestry to the eighth generation, finding his ancestry to be approximately 36% Spanish, 28% French, 11% German and 8% Italian, the rest being Slavic, English, Savoyard and Lorrainian.((French) Carretier, Christian (1980). Les Cinq Cent Douze Quartiers de Louis XIV. Angers-Paris.)

- ^ a b c d Buckley, Veronica. Madame de Maintenon: The Secret Wife of Louis XIV. London: Bloomsbury, 2008

- ^ Faroqhi, p.73 The Ottoman Empire and the World Around it [1]

- ^ The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art Page 98 by Michael Sullivan (1989) ISBN 0520212363 [2]

- ^ Barnes, Linda L. (2005) Needles, Herbs, Gods, and Ghosts: China, Healing, and the West to 1848 Harvard University Press ISBN 0674018729, p.85

- ^ Mungello, David E. (2005) The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500-1800 Rowman & Littlefield ISBN 074253815X, p.125

- ^ Lynn, John A. (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV (1667-1714). Longman New York. p.364.

- ^ a b Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon. "Historical Memoirs of the Duc de Saint-Simon, volume 1 1691-1709: The Court of Louis XIV". http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/17stsimon.html.

- ^ "Morganatic and Secret Marriages in the French Royal Family". http://www.heraldica.org/topics/france/morganat.htm. Retrieved on 2008-07-10.

- ^ For example, see Buckley, Veronica. Madame de Maintenon: The Secret Wife of Louis XIV. London: Bloomsbury, 2008

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia (2007). "Louis XIV, king of France". http://www.bartleby.com/65/lo/Louis14Fr.html. Retrieved on 2008-01-19.

- ^ Kamen, Henry. (2001) Philip V of Spain: The King who Reigned Twice Published by Yale University Press. ISBN 0300087187. p. 6

- ^ Napoleon Bonaparte, Napoleon’s Notes on English History made on the Eve of the French Revolution, illustrated from Contemporary Historians and referenced from the findings of Later Research by Henry Foljambe Hall. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1905, 258.

- ^ Hamilton, Walter. "Dated Book-plates (Ex Libris) with a Treatise on Their Origin", P37. Published 1895. A.C. Black

- ^ Edmunds, Martha. "Piety and Politics", P274. 2002. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0874136938

- ^ J-Y Tadié's annotations to The Vicomte de Bragelonne, Gallimard, 1997

[edit] Further reading

- Acton, J. E. E., 1st Baron. (1906). Lectures on Modern History. London: Macmillan and Co.

- Beik, William. "The Absolutism of Louis XIV as Social Collaboration: Review Article", Past and Present, no. 188 (August 2005), pp. 195–224.

- Bluche, François, Louis XIV, Paris: Hachette Littératures, 1986. (English translation by Mark Greengrass; published in 1990 by Franklin Watts.)

- Buckley, Veronica. Madame de Maintenon: The Secret Wife of Louis XIV. London: Bloomsbury, 2008

- Burke, Peter En kung blir till (Swedish translation of The fabrication of a king, 1992)

- Cambridge Modern History vol 5 The Age of Louis XIV (1908)]

- Carretier, Christian, "Les cinq cent douze quartiers de Louis XIV", Angers-Paris, 1980

- Chaline, Olivier, Le règne de Louis XIV (Paris: Flammarion, 2005)

- Church, William F. (ed.). The Greatness of Louis XIV. London: D.C. Heath and Company, 1972.

- Cronin, Vincent. Louis XIV. London: HarperCollins, 1996 (ISBN 0002720728)

- Dunlop, Ian. Louis XIV. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000 (hardcover, ISBN 0312261969)

- Erlanger, Philippe, Louis XIV, Librairie Arthème Fayard, Paris 1965, reprinted by Librairie Académique Perrin, Paris, 1978, (French).

- Erlanger, Philippe, Louis XIV, translated from the French by Stephen Cox, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1970, (English).

- Fraser, Antonia. Love and Louis XIV: The Women in the Life of the Sun King. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-297-82997-1); New York: Nan A. Talese, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0385509847)

- Goyau, G. (1910). "Louis XIV". The Catholic Encyclopedia. (Volume IX). New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Holt, Mack P., "Louis XIV." The New Book of Knowledge. Scholastic Library Publishing, 2005.

- Jordan, David. The King's Trial: Louis XVI vs. the French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004 (paperback, ISBN 0520236971)

- Lynn, John A., "The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714", New York: Longman, 1999

- Rubin, David Lee, ed. Sun King: The Ascendancy of French Culture during the Reign of Louis XIV. Washington: Folger Books and Cranbury: Associated University Presses, 1992.

- Steingrad, E. (2004). "Louis XIV."

- Thompson, Ian. The Sun King's Garden: Louis XIV, André Le Nôtre And the Creation of the Gardens of Versailles. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1582346313).

- Wolf, J. B. (1968). Louis XIV. New York: Norton.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Louis XIV of France |

- Chronology Louis XIV

- Memoirs of Louis XIV and His Court and of the Regency

- Full text of marriage contract (PDF), France National Archives transcription (French)

- "Le siècle de Louis XIV" by Voltaire, 1751

- List of films dedicated to Louis XIV and period[1] Of particular interest: Documentary on Versailles—The Visit.

|

Louis XIV of France

Cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty

Born: September 5 1638 Died: September 1 1715 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Louis XIII |

King of France and Navarre 14 May 1643 – 1 September, 1715 |

Succeeded by Louis XV |

| French royalty | ||

| Preceded by Louis XIII |

Dauphin of France 5 September 1638 – 14 May, 1643 |

Succeeded by Louis "le Grand Dauphin" |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[edit] References

- ^ "Louis XIV - the Sun King: Louis XIV - the Sun King". Louis-xiv.de. http://www.louis-xiv.de/index.php?t=films&a=films. Retrieved on 2008-08-31.

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Louis XIV of France |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | The Sun King, Louis the Great |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | King of France and of Navarre |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 5 September 1638 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1 September 1715 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Château de Versailles, Versailles, France |