Maunder Minimum

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

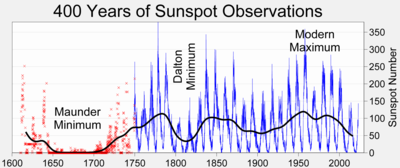

The Maunder Minimum is the name given to the period roughly from 1645 to 1715, when sunspots became exceedingly rare, as noted by solar observers of the time. It is named after the solar astronomer Edward W. Maunder (1851–1928) who studied changes of sunspots latitudes in different times and also during second part of 17th Century. Edward Maunder published two papers in 1890 and 1894 and he mentioned about earlier papers written by G. Sporer. The time of Minimum duration was taken from Sporer article.

During one 30-year period within the Maunder Minimum, astronomers observed only about 50 sunspots, as opposed to a more typical 40,000–50,000 spots in modern times.

Contents |

[edit] Sunspot observations

The Maunder Minimum occurred between 1645 and 1715 when only about 50 spots appeared as opposed to the typical 40,000–50,000 spots. The total numbers of sunspots (but not Wolf numbers) in different Years were as follows:

| Year | Sunspots |

|---|---|

| 1610 | 9 |

| 1620 | 6 |

| 1630 | 9 |

| 1640 | 0 |

| 1650 | 3 |

| 1660 | Some sunspots reported by Jan Heweliusz in "Machina Coelestis" |

| 1670 | 0 |

| 1680 | 1 huge sunspot observed by Gian Domenico Cassini |

During the Maunder Minimum enough sunspots were sighted so that 11-year cycles could be extrapolated from the count. The maxima occurred in 1676, 1684, 1695, 1705 and 1716.

The sunspot activity was then concentrated in the southern hemisphere of the Sun, except for the last cycle when the sunspots appeared in the northern hemisphere too.

According to Spörer's law, at the start of a cycle spots appear at ever lower latitudes, until they average at about lat. 15° at solar maximum. The average then continues to drift lower to about 7° and after that, while spots of the old cycle fade, new cycle spots start appearing again at high latitudes.

The visibility of these spots is also affected by the velocity of the sun's rotation at various latitudes:

| Solar latitude |

Rotation period (days) |

|---|---|

| 0° | 24.7 |

| 35° | 26.7 |

| 40° | 28.0 |

| 75° | 33.0 |

Visibility is somewhat affected by observations being done from the ecliptic. The ecliptic is inclined 7° from the plane of the Sun's equator (latitude 0°).

[edit] Little Ice Age

The Maunder Minimum coincided with the middle — and coldest part — of the Little Ice Age, during which Europe and North America, and perhaps much of the rest of the world, were subjected to bitterly cold winters. Whether there is a causal connection between low sunspot activity and cold winters is the subject of ongoing debate (e.g., see Global Warming).

[edit] Other observations

The lower solar activity during the Maunder Minimum also affected the amount of cosmic radiation reaching the Earth. The scale of changes resulting in the production of carbon-14 in one cycle is small (about 1 percent of medium abundance) and can be taken into account when radiocarbon dating is used to determine the age of archaeological artifacts.

Solar activity also affects the production of beryllium-10, and variations in that cosmogenic isotope are studied as a proxy for solar activity.

Other historical sunspot minima have been detected either directly or by the analysis of carbon-14 in tree rings; these include the Spörer Minimum (1450–1540), and less markedly the Dalton Minimum (1790–1820). In total there seem to have been 18 periods of sunspot minima in the last 8,000 years, and studies indicate that the sun currently spends up to a quarter of its time in these minima.

One recently published paper, based on an analysis of a Flamsteed drawing, suggests that the Sun's rotation slowed in the deep Maunder minimum (1684).[1]

During the Maunder Minimum auroras had been observed normally. Detailed analysis has been published by Wilfried Schröder[2] and J. P. Legrand et al.[3]

The fundamental papers on the Maunder minimum (Eddy, Legrand, Gleissberg, Schröder, Landsberg et al.) have been published in Case studies on the Spörer, Maunder and Dalton Minima.[4]

[edit] See also

- Solar minimum

- Jack Eddy An United States Astronomer.

[edit] References

- ^ Vaquero J.M., Sánchez-bajo F., Gallego M.C. (2002). "A Measure of the Solar Rotation During the Maunder Minimum". Solar Physics 207 (2): 219. doi:.

- ^ Schröder, Wilfried (1992). "On the existence of the 11-year cycle in solar and auroral activity before and during the so-called Maunder Minimum". Journal of Geomagnetism and Geoelectricity 44 (2): 119–128. ISSN 00221392.

- ^ Legrand, J. P.; Le Goff, M.; Mazaudier, C.; Schröder, W. (1992). "Solar and auroral activities during the seventeenth century". Acta Geophysics and Geodetica Hungarica 27 (2–4): 251–282.

- ^ Schröder, Wilfried (2005). Case studies on the Spörer, Maunder, and Dalton minima. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Geophysik und Kosmischen Physik. 6. Potsdam: AKGGP, Science Edition.

[edit] Further reading

- Luterbach, J.; et al. (2001). "The Late Maunder Minimum (1675–1715) – A Key Period for Studying Decadal Scale Climatic Change in Europe". Climatic Change 49 (4): 441–462. doi:.

- Willie Wei-Hock Soon; Yaskell, Steven H. (2003). The Maunder minimum and the variable sun-earth connection. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific. pp. 278. ISBN 9812382755.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||