Michelangelo

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni | |

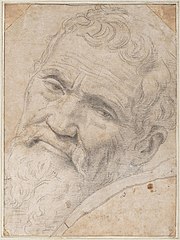

Chalk portrait of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra |

|

| Birth name | Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni |

| Born | March 6, 1475 near Arezzo, in Caprese, Tuscany |

| Died | February 18, 1564 (aged 88) Rome |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Field | sculpture, painting, architecture, and poetry |

| Training | Apprentice to Domenico Ghirlandaio[1] |

| Movement | High Renaissance |

| Works | David, The Creation of Adam, Pietà |

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni[1] (March 6, 1475 – February 18, 1564), commonly known as Michelangelo, was an Italian Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, poet, and engineer. Despite making few forays beyond the arts, his versatility in the disciplines he took up was of such a high order that he is often considered a contender for the title of the archetypal Renaissance man, along with his rival and fellow Italian Leonardo da Vinci.

Michelangelo's output in every field during his long life was prodigious; when the sheer volume of correspondence, sketches, and reminiscences that survive is also taken into account, he is the best-documented artist of the 16th century. Two of his best-known works, the Pietà and David, were sculpted before he turned thirty. Despite his low opinion of painting, Michelangelo also created two of the most influential works in fresco in the history of Western art: the scenes from Genesis on the ceiling and The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. Later in life he designed the dome of St. Peter's Basilica in the same city and revolutionised classical architecture with his use of the giant order of pilasters.

In a demonstration of Michelangelo's unique standing, he was the first Western artist whose biography was published while he was alive.[2] Two biographies were published of him during his lifetime; one of them, by Giorgio Vasari, proposed that he was the pinnacle of all artistic achievement since the beginning of the Renaissance, a viewpoint that continued to have currency in art history for centuries. In his lifetime he was also often called Il Divino ("the divine one").[3] One of the qualities most admired by his contemporaries was his terribilità, a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur, and it was the attempts of subsequent artists to imitate Michelangelo's impassioned and highly personal style that resulted in the next major movement in Western art after the High Renaissance, Mannerism.

Contents |

Biography

Early life

Michelangelo was born on March 6, 1475[a] in Caprese near Arezzo, Tuscany.[4] His family had for several generations been small-scale bankers in Florence but his father, Lodovico di Leonardo di Buonarroti di Simoni, failed to maintain the bank's financial status, and held occasional government positions.[2] At the time of Michelangelo's birth, his father was the Judicial administrator of the small town of Caprese and local administrator of Chiusi. Michelangelo's mother was Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena.[5] The Buonarrotis claimed to descend from the Countess Mathilde of Canossa; this claim remains unproven, but Michelangelo himself believed it.[6] Several months after Michelangelo's birth the family returned to Florence where Michelangelo was raised. At later times, during the prolonged illness and after the death of his mother when he was seven years old, Michelangelo lived with a stonecutter and his wife and family in the town of Settignano where his father owned a marble quarry and a small farm.[5] Giorgio Vasari quotes Michelangelo as saying, "If there is some good in me, it is because I was born in the subtle atmosphere of your country of Arezzo. Along with the milk of my nurse I received the knack of handling chisel and hammer, with which I make my figures."[4]

Michelangelo's father sent him to study grammar with the Humanist Francesco da Urbino in Florence as a young boy.[7][4][b] The young artist, however, showed no interest in his schooling, preferring to copy paintings from churches and seek the company of painters.[7] At thirteen, Michelangelo was apprenticed to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio.[1][8] When Michelangelo was only fourteen, his father persuaded Ghirlandaio to pay his apprentice as an artist, which was highly unusual at the time.[9] When in 1489 Lorenzo de' Medici, de facto ruler of Florence, asked Ghirlandaio for his two best pupils, Ghirlandaio sent Michelangelo and Francesco Granacci.[10] From 1490 to 1492, Michelangelo attended the Humanist academy which the Medici had founded along Neo Platonic lines. Michelangelo studied sculpture under Bertoldo di Giovanni. At the academy, both Michelangelo's outlook and his art were subject to the influence of many of the most prominent philosophers and writers of the day including Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola and Angelo Poliziano.[11] At this time Michelangelo sculpted the reliefs Madonna of the Steps (1490–1492) and Battle of the Centaurs (1491–1492). The latter was based on a theme suggested by Poliziano and was commissioned by Lorenzo de Medici.[12]

Early adulthood

Lorenzo de' Medici's death on April 8, 1492, brought a reversal of Michelangelo's circumstances.[13] Michelangelo left the security of the Medici court and returned to his father's house. In the following months he carved a wooden crucifix (1493), as a gift to the prior of the Florentine church of Santo Spirito, who had permitted him some studies of anatomy on the corpses of the church's hospital.[14] Between 1493 and 1494 he bought a block of marble for a larger than life statue of Hercules, which was sent to France and subsequently disappeared sometime circa 1700s.[12][c] On January 20, 1494, after heavy snowfalls, Lorenzo's heir, Piero de Medici commissioned a snow statue, and Michelangelo again entered the court of the Medici.

In the same year, the Medici were expelled from Florence as the result of the rise of Savonarola. Michelangelo left the city before the end of the political upheaval, moving to Venice and then to Bologna.[13] In Bologna he was commissioned to finish the carving of the last small figures of the Shrine of St. Dominic, in the church dedicated to that saint. Towards the end 1494, the political situation in Florence was calmer. The city, previously under threat from the French, was no longer in danger as Charles VIII had suffered defeats. Michelangelo returned to Florence but received no commissions from the new city government under Savonarola. He returned to the employment of the Medici.[15] During the half year he spent in Florence he worked on two small statues, a child St. John the Baptist and a sleeping Cupid. According to Condivi, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, for whom Michelangelo had sculpted St. John the Baptist, asked that Michelangelo "fix it so that it looked as if it had been buried" so he could "send it to Rome…pass [it off as] an ancient work and…sell it much better." Both Lorenzo and Michelangelo were unwittingly cheated out of the real value of the piece by a middleman. Cardinal Raffaele Riario, to whom Lorenzo had sold it, discovered that it was a fraud, but was so impressed by the quality of the sculpture that he invited the artist to Rome.[16] [d] This apparent success in selling his sculpture abroad as well as the conservative Florentine situation may have encouraged Michelangelo to accept the prelate's invitation.[15]

Rome

Michelangelo arrived in Rome June 25, 1496[17] at the age of 21. On July 4 of the same year, he began work on a commission for Cardinal Raffaele Riario, an over-life-size statue of the Roman wine god, Bacchus. However, upon completion, the work was rejected by the cardinal, and subsequently entered the collection of the banker Jacopo Galli, for his garden.

In November of 1497, the French ambassador in the Holy See commissioned one of his most famous works, the Pietà and the contract was agreed upon in August of the following year. The contemporary opinion about this work — "a revelation of all the potentialities and force of the art of sculpture" — was summarized by Vasari: "It is certainly a miracle that a formless block of stone could ever have been reduced to a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh."

In Rome, Michelangelo lived near the church of Santa Maria di Loreto. Here, according to the legend, he fell in love with Vittoria Colonna, marquise of Pescara and a poet.[citation needed] His house was demolished in 1874, and the remaining architectural elements saved by the new proprietors were destroyed in 1930. Today a modern reconstruction of Michelangelo's house can be seen on the Gianicolo hill.

Works

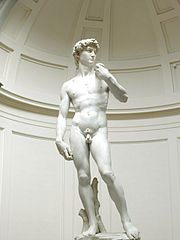

Statue of David

Michelangelo returned to Florence in 1499–1501. Things were changing in the republic after the fall of anti-Renaissance Priest and leader of Florence, Girolamo Savonarola (executed in 1498) and the rise of the gonfaloniere Pier Soderini. He was asked by the consuls of the Guild of Wool to complete an unfinished project begun 40 years earlier by Agostino di Duccio: a colossal statue portraying David as a symbol of Florentine freedom, to be placed in the Piazza della Signoria, in front of the Palazzo Vecchio. Michelangelo responded by completing his most famous work, the Statue of David in 1504. This masterwork, created out of a marble block from the quarries at Carrara that had already been worked on by an earlier hand, definitively established his prominence as a sculptor of extraordinary technical skill and strength of symbolic imagination.

Also during this period, Michelangelo painted the Holy Family and St John, also known as the Doni Tondo or the Holy Family of the Tribune: it was commissioned for the marriage of Angelo Doni and Maddalena Strozzi and in the 17th century hung in the room known as the Tribune in the Uffizi. He also may have painted the Madonna and Child with John the Baptist, known as the Manchester Madonna and now in the National Gallery, London.

Sistine Chapel ceiling

In 1505 Michelangelo was invited back to Rome by the newly elected Pope Julius II. He was commissioned to build the Pope's tomb. Under the patronage of the Pope, Michelangelo had to constantly stop work on the tomb in order to accomplish numerous other tasks. Because of these interruptions, Michelangelo worked on the tomb for 40 years. The tomb, of which the central feature is Michelangelo's statue of Moses, was never finished to Michelangelo's satisfaction. It is located in the Church of S. Pietro in Vincoli in Rome.

During the same period, Michelangelo took the commission to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which took approximately four years to complete (1508–1512). According to Michelangelo's account, Bramante and Raphael convinced the Pope to commission Michelangelo in a medium not familiar to the artist. This was done in order that he, Michelangelo, would suffer unfavorable comparisons with his rival Raphael, who at the time was at the peak of his own artistry as the primo fresco painter. However, this story is discounted by modern historians on the grounds of contemporary evidence, and may merely have been a reflection of the artist's own perspective.

Michelangelo was originally commissioned to paint the 12 Apostles against a starry sky, but lobbied for a different and more complex scheme, representing creation, the Downfall of Man and the Promise of Salvation through the prophets and Genealogy of Christ. The work is part of a larger scheme of decoration within the chapel which represents much of the doctrine of the Catholic Church

The composition eventually contained over 300 figures and had at its center nine episodes from the Book of Genesis, divided into three groups: God's Creation of the Earth; God's Creation of Humankind and their fall from God's grace; and lastly, the state of Humanity as represented by Noah and his family. On the pendentives supporting the ceiling are painted twelve men and women who prophesied the coming of the Jesus. They are seven prophets of Israel and five Sibyls, prophetic women of the Classical world.

Among the most famous paintings on the ceiling are the Creation of Adam, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the Great Flood, the Prophet Isaiah and the Cumaean Sibyl. Around the windows are painted the ancestors of Christ.

Under Medici Popes in Florence

In 1513 Pope Julius II died and his successor Pope Leo X, a Medici, commissioned Michelangelo to reconstruct the façade of the basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence and to adorn it with sculptures. Michelangelo agreed reluctantly. The three years he spent in creating drawings and models for the facade, as well as attempting to open a new marble quarry at Pietrasanta specifically for the project, were among the most frustrating in his career, as work was abruptly cancelled by his financially-strapped patrons before any real progress had been made. The basilica lacks a facade to this day.

Apparently not the least embarrassed by this turnabout, the Medici later came back to Michelangelo with another grand proposal, this time for a family funerary chapel in the basilica of San Lorenzo. Fortunately for posterity, this project, occupying the artist for much of the 1520s and 1530s, was more fully realized. Though still incomplete, it is the best example we have of the integration of the artist's sculptural and architectural vision, since Michelangelo created both the major sculptures as well as the interior plan. Ironically the most prominent tombs are those of two rather obscure Medici who died young, a son and grandson of Lorenzo. Il Magnifico himself is buried in an unfinished and comparatively unimpressive tomb on one of the side walls of the chapel, not given a free-standing monument, as originally intended.

In 1527, the Florentine citizens, encouraged by the sack of Rome, threw out the Medici and restored the republic. A siege of the city ensued, and Michelangelo went to the aid of his beloved Florence by working on the city's fortifications from 1528 to 1529. The city fell in 1530 and the Medici were restored to power. Completely out of sympathy with the repressive reign of the ducal Medici, Michelangelo left Florence for good in the mid-1530s, leaving assistants to complete the Medici chapel. Years later his body was brought back from Rome for interment at the Basilica di Santa Croce, fulfilling the maestro's last request to be buried in his beloved Tuscany.

Last works in Rome

The fresco of The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel was commissioned by Pope Clement VII, who died shortly after assigning the commission. Paul III was instrumental in seeing that Michelangelo began and completed the project. Michelangelo labored on the project from 1534 to October 1541. The work is massive and spans the entire wall behind the altar of the Sistine Chapel. The Last Judgment is a depiction of the second coming of Christ and the apocalypse; where the souls of humanity rise and are assigned to their various fates, as judged by Christ, surrounded by the Saints.

Once completed, the depictions of nakedness in the papal chapel was considered obscene and sacrilegious, and Cardinal Carafa and Monsignor Sernini (Mantua's ambassador) campaigned to have the fresco removed or censored, but the Pope resisted. After Michelangelo's death, it was decided to obscure the genitals ("Pictura in Cappella Ap.ca coopriantur"). So Daniele da Volterra, an apprentice of Michelangelo, was commissioned to cover with perizomas (briefs) the genitals, leaving unaltered the complex of bodies. When the work was restored in 1993, the conservators chose not to remove all the perizomas of Daniele, leaving some of them as a historical document, and because some of Michelangelo’s work was previously scraped away by the touch-up artist's application of “decency” to the masterpiece. A faithful uncensored copy of the original, by Marcello Venusti, can be seen at the Capodimonte Museum of Naples.

Censorship always followed Michelangelo, once described as "inventor delle porcherie" ("inventor of obscenities", in the original Italian language referring to "pork things"). The infamous "fig-leaf campaign" of the Counter-Reformation, aiming to cover all representations of human genitals in paintings and sculptures, started with Michelangelo's works. To give two examples, the marble statue of Cristo della Minerva (church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome) was covered by added drapery, as it remains today, and the statue of the naked child Jesus in Madonna of Bruges (The Church of Our Lady in Bruges, Belgium) remained covered for several decades. Also, the plaster copy of the David in the Cast Courts (Victoria and Albert Museum) in London, has a fig leaf in a box at the back of the statue. It was there to be placed over the statue's genitals so that they would not upset visiting female royalty.

In 1546, Michelangelo was appointed architect of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, and designed its dome. As St. Peter's was progressing there was concern that Michelangelo would pass away before the dome was finished. However, once building commenced on the lower part of the dome, the supporting ring, the completion of the design was inevitable.

Last sketch found

On December 7, 2007, Michelangelo's red chalk sketch for the dome of St Peter's Basilica, his last before his 1564 death, was discovered in the Vatican archives. It is extremely rare, since he destroyed his designs later in life. The sketch is a partial plan for one of the radial columns of the cupola drum of Saint Peter's.[18]

Architectural work

Michelangelo worked on many projects that had been started by other men, most notably in his work at St Peter's Basilica, Rome. The Campidoglio, designed by Michelangelo during the same period, rationalized the structures and spaces of Rome's Capitoline Hill. Its shape, more a rhomboid than a square, was intended to counteract the effects of perspective. The major Florentine architectural projects by Michelangelo are the unexecuted façade for the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence and the Medici Chapel (Capella Medicea) and Laurentian Library there, and the fortifications of Florence. The major Roman projects are St. Peter's, Palazzo Farnese, San Giovanni de' Fiorentini and the Sforza Chapel (Capella Sforzesca), Porta Pia and Santa Maria degli Angeli.

Laurentian Library

Around 1530 Michelangelo designed the Laurentian Library in Florence, attached to the church of San Lorenzo. He produced new styles such as pilasters tapering thinner at the bottom, and a staircase with contrasting rectangular and curving forms.

Medici Chapel

Michelangelo designed the Medici Chapel. The Medici Chapel has monuments in it dedicated to certain members of the Medici family. Michelangelo never finished it, so his pupils later completed it. Lorenzo the Magnificent was buried at the entrance wall of the Medici Chapel. Sculptures of the "Madonna and Child" and the Medici patron saints Cosmas and Damian were set over his burial. The "madonna and child" was Michelangelo's own work.

Personality

Michelangelo, who was often arrogant with others and constantly dissatisfied with himself, saw art as originating from inner inspiration and from culture. In contradiction to the ideas of his rival, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo saw nature as an enemy that had to be overcome. The figures that he created are forceful and dynamic, each in its own space apart from the outside world. For Michelangelo, the job of the sculptor was to free the forms that were already inside the stone. He believed that every stone had a sculpture within it, and that the work of sculpting was simply a matter of chipping away all that was not a part of the statue.[citation needed]

Several anecdotes reveal that Michelangelo's skill, especially in sculpture, was greatly admired in his own time. Another Lorenzo de Medici wanted to use Michelangelo to make some money. He had Michelangelo sculpt a cupid that looked worn and old. Lorenzo paid Michelangelo 30 ducats, but sold the cupid for 200 ducats. Cardinal Raffaele Riario became suspicious and sent someone to investigate. The man had Michelangelo do a sketch for him of a cupid, and then told Michelangelo that while he received 30 ducats for his cupid, Lorenzo had passed the cupid off for an antique and sold it for 200 ducats. Michelangelo then confessed that he had done the cupid, but had no idea that he had been cheated. After the truth was revealed, the Cardinal later took this as proof of his skill and commissioned his Bacchus. Another better-known anecdote claims that when finishing the Moses (San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome), Michelangelo violently hit the knee of the statue with a hammer, shouting, "Why don't you speak to me?"[citation needed]

In his personal life, Michelangelo was abstemious. He told his apprentice, Ascanio Condivi: "However rich I may have been, I have always lived like a poor man."[19] Condivi said he was indifferent to food and drink, eating "more out of necessity than of pleasure"[19] and that he "often slept in his clothes and ... boots."[19] These habits may have made him unpopular. His biographer Paolo Giovio says, "His nature was so rough and uncouth that his domestic habits were incredibly squalid, and deprived posterity of any pupils who might have followed him."[20] He may not have minded, since he was by nature a solitary and melancholy person. He had a reputation for being bizzarro e fantastico because he "withdrew himself from the company of men." [21]

Sexuality

Fundamental to Michelangelo's art is his love of male beauty, which attracted him both aesthetically and emotionally. In part, this was an expression of the Renaissance idealization of masculinity. But in Michelangelo's art there is clearly a sensual response to this aesthetic.[22]

The sculptor's expressions of love have been characterized as both Neoplatonic and openly homoerotic; recent scholarship seeks an interpretation which respects both readings, yet is wary of drawing absolute conclusions. One example of the conundrum is Cecchino dei Bracci, whose death, only a year after their meeting in 1543, inspired the writing of forty eight funeral epigrams, which by some accounts allude to a relationship that was not only romantic but physical as well:

La carne terra, e qui l'ossa mia, prive

de' lor begli occhi, e del leggiadro aspetto

fan fede a quel ch'i' fu grazia nel letto,

che abbracciava, e' n che l'anima vive.[23]

or

The flesh now earth, and here my bones,

Bereft of handsome eyes, and jaunty air,

Still loyal are to him I joyed in bed,

Whom I embraced, in whom my soul now lives.

According to others, they represent an emotionless and elegant re-imagining of Platonic dialogue, whereby erotic poetry was seen as an expression of refined sensibilities (Indeed, it must be remembered that professions of love in 16th century Italy were given a far wider application than now).[24] Some young men were street wise and took advantage of the sculptor. Febbo di Poggio, in 1532, peddled his charms—in answer to Michelangelo's love poem he asks for money. Earlier, Gherardo Perini, in 1522, had stolen from him shamelessly. Michelangelo defended his privacy above all. When an employee of his friend Niccolò Quaratesi offered his son as apprentice suggesting that he would be good even in bed, Michelangelo refused indignantly, suggesting Quaratesi fire the man.

The greatest written expression of his love was given to Tommaso dei Cavalieri (c. 1509–1587), who was 23 years old when Michelangelo met him in 1532, at the age of 57. Cavalieri was open to the older man's affection: I swear to return your love. Never have I loved a man more than I love you, never have I wished for a friendship more than I wish for yours. Cavalieri remained devoted to Michelangelo till his death.

Michelangelo dedicated to him over three hundred sonnets and madrigals, constituting the largest sequence of poems composed by him. Some modern commentators assert that the relationship was merely a Platonic affection, even suggesting that Michelangelo was seeking a surrogate son.[25] However, their homoerotic nature was recognized in his own time, so that a decorous veil was drawn across them by his grand nephew, Michelangelo the Younger, who published an edition of the poetry in 1623 with the gender of pronouns changed. John Addington Symonds, the early British homosexual activist, undid this change by translating the original sonnets into English and writing a two-volume biography, published in 1893.

The sonnets are the first large sequence of poems in any modern tongue addressed by one man to another, predating Shakespeare's sonnets to his young friend by a good fifty years.

- I feel as lit by fire a cold countenance

- That burns me from afar and keeps itself ice-chill;

- A strength I feel two shapely arms to fill

- Which without motion moves every balance.

-

-

- — (Michael Sullivan, translation)

-

Late in life he nurtured a great love for the poet and noble widow Vittoria Colonna, whom he met in Rome in 1536 or 1538 and who was in her late forties at the time. They wrote sonnets for each other and were in regular contact until she died, though many scholars note the intellectualized or spiritual quality of this passion.

It is impossible to know for certain whether Michelangelo had physical relationships (Condivi ascribed to him a "monk-like chastity"),[26] but through his poetry and visual art we may at least glimpse the arc of his imagination.[27]

See also

The asteroid 3001 Michelangelo and a crater on the planet Mercury were named after Michelangelo.[28] The character Michelangelo from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles was named after Michelangelo.

Footnotes

- a. ^ Michelangelo's father marks the date as March 6, 1474 in the Florentine manner ab Incarnatione. However, in the Roman manner, ab Nativitate, it is 1475.

- b. ^ Sources disagree as to how old Michelangelo was when he departed for school. De Tolnay writes that it was at ten years old while Sedgwick notes in her translation of Condivi that Michelangelo was seven.

- c. ^ The Strozzi family acquired the sculpture Hercules. Filippo Strozzi sold it to Francis I in 1529. In 1594, Henry IV installed it in the Jardin d'Estang at Fontainebleau where it disappeared in 1713 when the Jardin d'Estange was destroyed.

- d. ^ Vasari makes no mention of this episode and Paolo Giovio's Life of Michelangelo indicates that Michelangelo tried to pass the statue off as an antique himself.

References

- ^ a b c "Web Gallery of Art, image collection, virtual museum, searchable database of European fine arts (1100–1850)". www.wga.hu. http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/bio/m/michelan/biograph.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-13.

- ^ a b Michelangelo. (2008). Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite.

- ^ Jacobs, Frederika (September 2002), "assembling: Marsyas, Michelangelo, and the Accademia del Disegno - Dis", The Art Bulletin: 22, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0422/is_3_84/ai_91673178/pg_22

- ^ a b c J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 11

- ^ a b C. Clément, Michelangelo, 5

- ^ A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, 5

- ^ a b A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, 9

- ^ R. Liebert, Michelangelo: A Psychoanalytic Study of his Life and Images, 59

- ^ C. Clément, Michelangelo, 7

- ^ C. Clément, Michelangelo, 9

- ^ J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 18–19

- ^ a b A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, 15

- ^ a b J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 20–21

- ^ A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, 17

- ^ a b J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 24–25

- ^ A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, 19–20

- ^ J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 26–28

- ^ "Michelangelo 'last sketch' found". BBC News. 2007-12-07. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7133116.stm. Retrieved on 2009-02-09.

- ^ a b c Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, p. 106.

- ^ Paola Barocchi (ed.) Scritti d'arte del cinquecento, Milan, 1971; vol. I p. 10.

- ^ Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, p. 102.

- ^ Hughes, Anthony: "Michelangelo"., page 327. Phaidon, 1997.

- ^ "MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI" by Giovanni Dall'Orto Babilonia n. 85, January 1991, pp. 14–16 [1]

- ^ Hughes, Anthony: "Michelangelo.", page 326. Phaidon, 1997.

- ^ "Michelangelo", The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, Macropaedia, Volume 24, page 58, 1991. The text goes so far as to claim, a bit defensively, 'These have naturally been interpreted as indications that Michelangelo was a homosexual, but such a reaction according to the artist's own statement would be that of the ignorant'.

- ^ Hughes, Anthony: "Michelangelo"., page 326. Phaidon, 1997.

- ^ Scigliano, Eric: "Michelangelo's Mountain; The Quest for Perfection in the Marble Quarries of Carrara.", Simon and Schuster, 2005. [2]. Retrieved January 27, 2007

- ^ Gallant, R., 1986. National Geographic Picture Atlas of Our Universe. National Geographic Society, 2nd edition. ISBN 0870446444

Further reading

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Michelangelo |

- Ackerman, James (1986). The Architecture of Michelangelo. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226002408.

- Clément, Charles (1892). Michelangelo. Harvard University, Digitized June 25, 2007: S. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, ltd.: London. http://books.google.com/books?id=G-sDAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=michelangelo&as_brr=1#PPA1,M1.

- Condivi, Ascanio; Alice Sedgewick (1553). The Life of Michelangelo. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01853-4.

- Baldini, Umberto; Liberto Perugi (1982). The Sculpture of Michelangelo. Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0447-x. http://www.antiqbook.com/boox/laurie/50121.shtml.

- Einem, Herbert von (1973). Michelangelo. Trans. Ronald Taylor. London: Methuen.

- Gilbert, Creighton (1994). Michelangelo On and Off the Sistine Ceiling. New York: George Braziller.

- Hart, Michael (1992). The 100. Carol. ISBN 0-8065-1350-0.

- Hibbard, Howard (1974). Michelangelo. New York: Harper & Row.

- Hirst, Michael and Jill Dunkerton. (1994) The Young Michelangelo: The Artist in Rome 1496-1501. London: National Gallery Publications.

- Liebert, Robert (1983). Michelangelo: A Psychoanalytic Study of his Life and Images. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02793-1.

- Pietrangeli, Carlo, et al. (1994). The Sistine Chapel: A Glorious Restoration. New York: Harry N. Abrams

- Sala, Charles (1996). Michelangelo: Sculptor, Painter, Architect. Editions Pierre Terrail. ISBN 978-2879390697.

- Saslow, James M. (1991). The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Annotated Translation. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Seymour, Charles, Jr. (1972). Michelangelo: The Sistine Chapel Ceiling. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Stone, Irving (1987). The Agony and the Ecstasy. Signet. ISBN 0-451-17135-7.

- Summers, David (1981). Michelangelo and the Language of Art. Princeton University Press.

- Tolnay, Charles (1947). The Youth of Michelangelo. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tolnay, Charles de. (1964). The Art and Thought of Michelangelo. 5 vols. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Néret, Gilles (2000). Michelangelo. Taschen. ISBN 9783822859766.

- Wilde, Johannes (1978). Michelangelo: Six Lectures. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Michelangelo Buonarroti |

- Michelangelo in the "A World History of Art"

- Michelangelo in the "Vatican Secret Archives"

- Photographs of details at the Campidoglio

- "The Michelangelo Code", suggesting Michelangelo's coded use of his knowledge of anatomy.

- Works by Michelangelo Buonarroti at Project Gutenberg

- The Digital Michelangelo Project

- The BP Special Exhibition Michelangelo Drawings - closer to the master

- Michelangelo's Drawings: Real or Fake? How to decide if a drawing is by Michelangelo.

- Michelangelo's Florence

- Models Michelangelo used to make his sculptures and paintings

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Michelangelo |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Buonarroti, Michelangelo; Buonarroti, Michelangelo di Lodovico |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Sculptor, painter and architect |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 6, 1475 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Caprese, Italy |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 18, 1564 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Rome, Italy |