Jack the Ripper

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Jack the Ripper | |

|---|---|

"A Suspicious Character," from The Illustrated London News for 13 October 1888 carrying the overall caption, "With the Vigilance Committee in the East End". |

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name: | unknown |

| Alias(es): | Jack the Ripper |

| Cause of death: | Unknown |

| Killings | |

| Number of victims: | 5+ |

| Country: | United Kingdom |

| Date apprehended: | Not apprehended |

Jack the Ripper is an alias given to an unidentified serial killer[1] active in the largely impoverished Whitechapel area and adjacent districts of London, England, in late 1888. The name originated in a letter sent to the London Central News Agency by someone claiming to be the murderer.

The victims were women earning income as prostitutes. Most victims' throats were slit, after which the bodies were mutilated. The removal of internal organs from three of the victims led some officials at the time of the murders to propose that the killer possessed anatomical or surgical knowledge.[2]

Newspapers, whose circulation had been growing during this era,[3] bestowed widespread and enduring notoriety on the killer because of the savagery of the attacks and the failure of the police to capture the murderer (they sometimes missed him at the crime scenes by mere minutes).[4][5]

Because the killer's identity has never been confirmed, the legends surrounding the murders have become a combination of genuine historical research, folklore, and pseudohistory. Many authors, historians, and amateur detectives have proposed theories about the identity of the killer and his victims.

Contents |

[edit] Background

In the mid 19th century, England experienced a rapid influx of mainly Irish immigrants, who swelled the populations of both the largely poor English countryside and England's major cities. From 1882, Jewish refugees escaping the pogroms in Tsarist Russia and eastern Europe added to the overcrowding and the already worsening work and housing conditions.[4] London, especially the East End and the civil parish of Whitechapel, became increasingly overcrowded, resulting in the development of a massive economic underclass.[6] This endemic poverty drove many women to prostitution. In October 1888, the London Metropolitan Police estimated that there were 1,200 prostitutes "of very low class" resident in Whitechapel and about 62 brothels.[7] The economic problems were accompanied by a steady rise in social tensions. In 1886–1889, demonstrations by the hungry and unemployed were a regular feature of London policing.[4]

The murders most often attributed to Jack the Ripper occurred in the latter half of 1888, though the series of brutal killings in Whitechapel persisted at least until 1891. A number of the murders involved extremely gruesome acts, such as mutilation and evisceration, which were widely reported in the media. Rumours that the murders were connected intensified in September and October, when a series of media outlets and Scotland Yard received a series of extremely disturbing letters from a writer or writers purporting to take responsibility for some or all of the murders. One letter, received by George Lusk, of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, included a preserved human kidney. Mainly because of the extraordinarily brutal character of the murders, and because of media treatment of the events, the public came increasingly to believe in a single serial killer terrorizing the residents of Whitechapel, nicknamed "Jack the Ripper" after the signature on a postcard received by the Central News Agency. Although the investigation was unable to connect the later killings conclusively to the murders of 1888, the legend of Jack the Ripper solidified.

[edit] Known victims

Metropolitan Police files show that the investigation began in 1888 and eventually came to encompass eleven separate murders, stretching from 3 April 1888 to 13 February 1891, known in the police docket as the "Whitechapel murders".[8] In addition, authors and historians have connected at least seven other murders and violent attacks with Jack the Ripper. Among the eleven murders actively investigated by the police, five are almost universally agreed upon as the work of a single killer, collectively called the "canonical five" victims:

- Mary Ann Nichols (nickname, "Polly"), killed Friday 31 August 1888. Her body was discovered by a man named Charles Cross at about 3:40 A.M. on the ground in front of a gated stable entrance in Buck's Row (now Durward Street), a back street in Whitechapel 200 yards from the London Hospital. Her throat was severed deeply by two cuts; the lower part of the abdomen was partly ripped open by a deep, jagged wound. There also were several incisions running across the abdomen, and three or four similar cuts on the right side caused by the same knife used violently and downwards.

- Annie Chapman (maiden name, Eliza Ann Smith; nickname, "Dark Annie"), killed Saturday 8 September 1888. Her body was discovered about 6 A.M., lying on the ground near a doorway in the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields. Like Mary Ann Nichols's, her throat was severed by two cuts, one deeper than the other. The abdomen was ripped entirely open and the uterus was removed.

- Elizabeth Stride (nickname, "Long Liz"), killed Sunday 30 September 1888. Her body was discovered about 1 A.M., lying on the ground in Dutfield's Yard, off Berner Street (now Henriques Street) in Whitechapel. There was one clear-cut incision on the neck; the cause of death was massive blood loss from the nearly severed main artery on the left side. The cut through the tissues on the right side was more superficial, and tapered off below the right jaw. That there also were no mutilations to the abdomen has left some uncertainty about the identity of Elizabeth's murderer, along with the suggestion her killer was disturbed during the attack.

- Catherine Eddowes (also known as "Kate Conway" and "Mary Ann Kelly," from the surnames of her two common-law husbands, Thomas Conway and John Kelly), killed Sunday 30 September 1888 (the same day as the previous victim, Elizabeth Stride). Her body was found in Mitre Square, in the City of London. The throat was, as in the former two cases, severed by two cuts; the abdomen was ripped open by a long, deep, jagged wound. The left kidney and the major part of the uterus had been removed. She was 46. Her murder, and the murder of Elizabeth Stride would go on to be called "The Double Event," in the media, and across London.

- Mary Jane Kelly (called herself "Marie Jeanette Kelly" after a trip to Paris; nickname, "Ginger"), killed Friday 9 November 1888. Her gruesomely mutilated body was discovered shortly after 10:45 A.M., lying on the bed in the single room where she lived at 13 Miller's Court, off Dorset Street, Spitalfields. Her throat had been severed down to the spine, and her abdomen virtually emptied of its organs. Her heart was missing.

The authority of this list rests on a number of authors' opinions, but historically the idea has been based upon the 1894 notes of Sir Melville Macnaghten, Chief Constable of the Metropolitan Police Service Criminal Investigation Department.[4] Macnaghten did not join the force until the year after the murders; and his memorandum, which came to light in 1959, contains serious factual errors about possible suspects. There is considerable disagreement about the value of Macnaghten's assessment of the number of victims. Some researchers have posited that the series may not have been the work of a single murderer, but of an unknown larger number of killers acting independently. Authors Stewart P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow argue that the "canonical five" is a "Ripper myth" and that the probable number of victims could range from three (Nichols, Chapman, and Eddowes) to six (the previous three, plus Stride, Kelly, and Martha Tabram) or more. Macnaghten's opinion of which crimes were committed by the same killer was not shared by other investigating officers, such as Inspector Frederick Abberline.[9]

Except Stride, whose attack may have been interrupted, mutilations of the "canonical five" victims became increasingly severe as the series of murders proceeded. Nichols and Stride were not missing any organs; but Chapman's uterus was taken, and Eddowes had her uterus and a kidney carried away and her face mutilated. While only Kelly's heart was missing from her crime scene, many of her internal organs were removed and left in her room.

The "canonical five" murders were generally perpetrated in the dark of night, on or close to a weekend, in a secluded site to which the public could gain access, and on a pattern of dates either at the end of a month or a week or so after. Yet every case differed from this pattern in some manner. Besides the differences already mentioned, Eddowes was the only victim killed within the City of London, though close to the boundary between the City and the metropolis. Nichols was the only victim to be found on an open street, albeit a dark and deserted one. Many sources state that Chapman was killed after the sun had started to rise, though that was not the opinion of the police or the doctors who examined the body.[10] Kelly's murder ended six weeks of inactivity for the murderer. (A week elapsed between the Nichols and Chapman murders; three between Chapman and the "double event".)

The large number of horrific attacks against women during this era adds some uncertainty as to exactly how many victims were killed by the same man. Most experts point to deep throat slashes, abdominal and genital-area mutilation, removal of internal organs, and progressive facial mutilations as the distinctive features of Jack the Ripper's modus operandi.

[edit] Other victims in the Whitechapel murder file

Six other Whitechapel murders were investigated by the Metropolitan Police at the time, two of which occurred before the "canonical five" and four after. Figures involved in the investigation and later authors have attributed some of these to Jack the Ripper.

These two murders occurred before the "canonical five":

- Emma Elizabeth Smith was attacked on Osborn Street, Whitechapel, on 3 April 1888; a blunt object was inserted into her vagina. She survived the attack and walked back to her lodging-house. Friends brought her to a hospital, where she told police that she was attacked by two or three men, one of whom was a teenager. She fell into a coma and died on 5 April 1888.[9] According to Dr. G. H. Hillier, attending surgeon at the London Hospital, the injuries indicated use of great force, which caused a rupture of the peritoneum and other internal organs, this led to peritonitis, which he deemed the cause of death.[11]

- Martha Tabram (sometimes spelled as Tabran; maiden name, Martha White; alias, Emma Turner), killed 7 August 1888. She had a total of 39 stab wounds. Of the non-canonical Whitechapel murders, Tabram is considered another possible Ripper victim for a variety of reasons. The geographic (George Yard Buildings, George Yard, Whitechapel.) and period proximity to the attacks considered likely to be those of the Ripper, and is compounded by the evident lack of obvious motive and the attack's noted savagery. However, the attack differs from those of the canonical ones in that the attack consisted of stabbing as opposed to slashing the throat and postmortem injuries. [9]

These four murders happened after the "canonical five":

- Rose Mylett (true name probably Catherine Mylett, but was also known as Catherine Millett, Elizabeth "Drunken Lizzie" Davis, "Fair" Alice Downey, or simply "Fair Clara") was reportedly strangled "by a cord drawn tightly round the neck" on 20 December 1888, though some investigators believed that she had accidentally suffocated herself on the collar of her dress while in a drunken stupor. Her body was found in Clarke's Yard, High Street, Poplar.

- Alice McKenzie (nicknamed "Clay Pipe" Alice and sometimes used the alias Alice Bryant), a prostitute, was killed on 17 July 1889. She reportedly died from "severance of the left carotid artery", but several minor bruises and cuts were found on the body. Her body was found in Castle Alley, Whitechapel. Police Commissioner James Monro initially believed this to be a Ripper murder and one of the pathologists examining the body, Dr Bond, agreed, though later writers have been more circumspect. Evans and Rumbelow suggest that the unknown murderer tried to make it look like a Ripper killing to deflect suspicion from himself.[9]

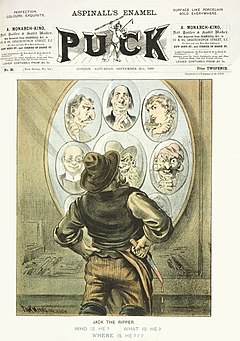

- "The Pinchin Street Torso" – a headless and legless torso of a woman found under a railway arch in Pinchin Street, Whitechapel on 10 September 1889. The mutilations were similar to the body which was the subject of the "The Whitehall Mystery", though in this case the hands were not severed. It seems probable that the murder had been committed elsewhere and that parts of the dismembered body were dumped at the crime scene.[9] Speculation, at the time, that the remains were of Lydia Hart, a prostitute who had recently disappeared, was disproved when she was soon located in a local infirmary where she was receiving medical treatment to cure the after effects of a "bit of a spree". The identity of the victim was never established. "The Whitehall Mystery" and "The Pinchin Streets Murderer" have been suggested to be part of a series of murders, called the "Thames Mysteries" or "Embankment Murders", committed by a single serial killer, dubbed the "Torso Killer".[12][13] Whether Jack the Ripper and the "Torso Killer" were the same person or separate serial killers active in the same area has long been debated.[14] The Pinchin Street murder prompted a revival of interest in the Ripper—manifested in an illustration from "Puck" showing the Ripper, from behind, looking in a mirror at alternate reflections embodying current speculation as to whom he might be: a doctor, a cleric, a woman, a Jew, a bandit or a policeman.[9]

- Frances Coles (also known as Frances Coleman, Frances Hawkins and nicknamed "Carrotty Nell") was killed on 13 February 1891. Minor wounds on the back of the head suggest that she was thrown violently to the ground before her throat was cut. Otherwise there were no mutilations to the body. Her body was found under a railway arch at Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel. A man named James Thomas Sadler, seen earlier with her, was arrested by the police and charged with her murder and was briefly thought to be the Ripper himself. However he was discharged from court due to lack of evidence on 3 March 1891. After this eleventh and last "Whitechapel Murder" the case was closed.[9]

[edit] Other alleged Ripper victims

In addition to the eleven murders officially investigated by the Metropolitan Police as part of the Ripper investigation, various Ripper historians have at times suggested a number of other contemporary attacks as possibly being connected to the same serial killer. In some cases, the records are not clear if the murders had even occurred or if the stories were fabricated later as a part of Ripper lore.

"Fairy Fay," a nickname for an unknown murder victim allegedly found on 26 December 1887 with "a stake thrust through her abdomen". It has been suggested that "Fairy Fay" was a creation of the press based upon confusion of the details of the murder of Emma Elizabeth Smith with a separate non-fatal attack the previous Christmas.[15] The name of "Fairy Fay" was first used for this alleged victim in 1950.[16] There were no recorded murders in Whitechapel at or around Christmas 1886 or 1887, and later newspaper reports that included a Christmas 1887 killing conspicuously did not list the Smith murder. Most authors agree that "Fairy Fay" never existed.[15][17]

Annie Millwood, born c. 1850, reportedly the victim of an attack on 25 February 1888. She was admitted to hospital with "numerous stabs in the legs and lower part of the body". She was discharged from hospital but died from apparently natural causes on 31 March 1888.[17]

Ada Wilson, reportedly the victim of an attack on 28 March 1888, resulting in two stabs in the neck. She survived the attack.

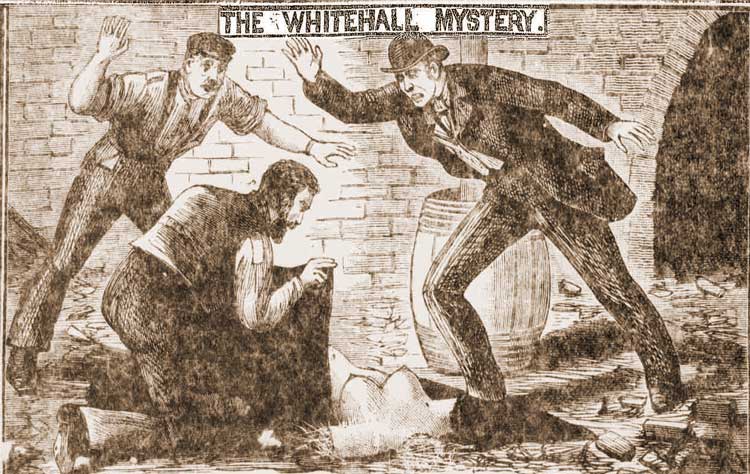

"The Whitehall Mystery", a term coined for the headless torso of a woman found in the basement of the new Metropolitan Police headquarters being built in Whitehall on 2 October 1888. An arm belonging to the body had previously been discovered floating in the River Thames near Pimlico, and one of the legs was subsequently discovered buried near where the torso was found. The other limbs and head were never recovered and the body never identified.

Annie Farmer, born c. 1848, reportedly was the victim of an attack on 21 November 1888. She survived with only a superficial cut on her throat, apparently caused by a blunt knife. Police suspected that the wound was self-inflicted and did not investigate the case further.

Elizabeth Jackson, a prostitute whose various body parts were collected from the River Thames between 31 May and 25 June 1889. She was reportedly identified by scars she had had prior to her disappearance and apparent murder.

Carrie Brown (nicknamed "Shakespeare",[18] reportedly for quoting William Shakespeare's sonnets) was killed 24 April 1891 in Manhattan, New York City. She was strangled with clothing and then mutilated with a knife. Her body was found with a large tear through her groin area and superficial cuts on her legs and back. No organs were removed from the scene, though an ovary was found upon the bed. Whether it was purposely removed or unintentionally dislodged during the mutilation is unknown. At the time, the murder was compared to those in Whitechapel though the Metropolitan Police eventually ruled out any connection.[19]

[edit] Investigation

The surviving Whitechapel Murders police files allow a quite detailed view of investigative procedure in Victorian times. A large team of policemen conducted house-to-house inquiries, lists of suspects were drawn up and many were interviewed, forensic material was collected and examined. A close reading of the investigation shows a basic process of identifying suspects, tracing them and deciding whether to examine them more closely or to cross them off the list. This is still the pattern of a major inquiry today.[20] The investigation was initially conducted by Whitechapel (H) Division C.I.D. headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid. After the Nichols murder, Detective Inspectors Frederick Abberline, Henry Moore, and Walter Andrews were sent from Central Office at Scotland Yard to assist. After the Eddowes murder, which occurred within the City of London, the City Police under Detective Inspector James McWilliam were also engaged. However, overall direction of the murder enquiries was confused and hampered by the fact that the newly appointed head of the CID, Sir Robert Anderson, was on leave in Switzerland between 7 September and 15 October, during which time Chapman, Stride and Eddowes were killed. This prompted the Chief Commissioner of the Met., Sir Charles Warren, to appoint Superintendent Donald Swanson to coordinate the enquiry from Scotland Yard. Swanson's notes on the case survive and are a valuable record of the investigation.[4]

Due in part to dissatisfaction with the police effort, a group of volunteer citizens in London's East End called the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee also patrolled the streets of London looking for suspicious characters, petitioned the government to raise a reward for information about the killer, and hired private detectives to question witnesses separate from the police. The committee was led by George Lusk in 1888. Albert Bachert, in 1889, claimed to be in charge of that group or a similar group.

[edit] Writing on the wall

After the murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes during the night of 30 September, police searched the area near the crime scenes in an effort to locate a suspect, witnesses or evidence. At about 3:00 a.m., Constable Alfred Long discovered a bloodstained piece of an apron in the stairwell of a tenement on Goulston Street. The cloth was later confirmed as being a part of the apron worn by Catherine Eddowes. There was writing in white chalk on the wall (or, in some accounts, the door jamb[9]) above where the apron was found. Long reported that it read, "The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing."[21] The writing is referred to by a number of authors as the "Goulston Street Graffito".[17][3][22] Detective Daniel Halse (City of London Police), arrived a short time later, and took down a different version: "The Juwes are not the men who will be blamed for nothing."[23] A copy according with Long's version of the message was taken down and attached to a report from Chief Commissioner Sir Charles Warren to the Home Office. Police Superintendent Thomas Arnold visited the scene and saw the writing. Later, in his report of 6 November to the Home Office, he claimed, that with the strong feeling against the Jews already existing, the message might have become the means of causing a riot:

"I beg to report that on the morning of the 30th of September, last my attention was called to some writing on the wall of the entrance to some dwellings No. 108 Goulston Street, Whitechapel which consisted of the following words: 'The Juews are not [the word 'not' being deleted] the men that will not be blamed for nothing,' and knowing in consequence of suspicion having fallen upon a Jew named John Pizer alias 'Leather Apron,' having committed a murder in Hanbury Street a short time previously, a strong feeling existed against the Jews generally, and as the building upon which the writing was found was situated in the midst of a locality inhabited principally by that sect, I was apprehensive that if the writing were left it would be the means of causing a riot and therefore considered it desirable that it should be removed having in view the fact that it was in such a position that it would have been rubbed by persons passing in & out of the building."[24]

Since the Nichols murder, rumours had been circulating in the East End that the killings were the work of a Jew dubbed "Leather Apron". Religious tensions were already high, and there had already been many near-riots. Arnold ordered a man to be standing by with a sponge to erase the writing, while he consulted Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren. Covering it in order to allow time for a photographer to arrive was considered, but Arnold and Warren (who personally attended the scene) considered this to be too dangerous, and Warren later stated he "considered it desirable to obliterate the writing at once".[25]

While the Goulston Street Graffito was found in Metropolitan Police territory, the apron piece was from a victim killed in the City of London, which has a separate police force. Some officers disagreed with Arnold and Warren's decision, especially those representing the City of London Police, who thought the writing constituted part of a crime scene and should at least be photographed before being erased, but it was wiped from the wall at 5:30 a.m.[26] Most contemporary police concluded that the text was a semi-literate attack on the area's Jewish population. Several possible explanations have been suggested as to the importance of this possible clue:

- According to historian Philip Sugden there are at least three permissible interpretations of this particular clue: "All three are feasible, not one capable of proof." The first is that the writing was not the work of the murderer at all. The apron piece was dropped by the writer, either by accident or design. The second would be to "take the murderer at his word"—a Jew incriminating himself and his people. The third interpretation was, according to Sugden, the one most favoured at the Scotland Yard and by "Old Jewry": The chalk message was a deliberate subterfuge, designed to incriminate the Jews and throw the police off the track of the real murderer.[27]

"But suppose the killer happened to throw the apron, quite fortuitously, down by the existing piece of graffiti? In such a case we would be utterly wrong in according to the writing any significance whatsoever. Walter Dew was inclined to endorse this approach to the problem. (...) Constable Halse, on the other hand, saw it and thought it looked recent. And Chief Inspector Henry Moore and Sir Robert Anderson are both on record as having explicitly stated their belief that the message was written by the murderer."[28]

- Author Martin Fido notes that the writing included a double negative, a common feature of Cockney speech. He suggests that the writing might be translated into standard English as "The Jews are men who will not take responsibility for anything" and that the message was written by someone who believed he or she had been wronged by one of the many Jewish merchants or tradesmen in the area.

- A contemporaneous explanation was offered by Robert Donston Stephenson (20 April 1841 – 9 October 1916), a journalist and writer known to be interested in the occult and black magic. In an article (signed 'One Who Thinks He Knows') in the Pall Mall Gazette of 1 December 1888, Stephenson concluded from the overall sentence construction, the double negative, the double designation "the Juwes are the men," and the highly unusual misspelling that the Ripper most probably was of French-speaking origin.[29] This claim was disputed by a native French speaker in a letter to the editor of that same publication that ran on 6 December.[30]

- Author Stephen Knight suggested that "Juwes" referred not to "Jews," but to Jubela, Jubelo and Jubelum, the three killers of Hiram Abiff, a semi-legendary figure in Freemasonry, and furthermore, that the message was written by the killer (or killers) as part of a Masonic plot.[31] There is, however, no evidence that anyone prior to Knight had ever referred to those three figures by the term "Juwes."

[edit] Criminal profiling

After the acquittal of Daniel M'Naghten in 1843, and the establishment of the M'Naghten rules, physicians became increasingly involved in determining whether defendants in murder cases were suffering from 'mental illness'. And the growing importance of the medical sciences during the same period also led to an increasing involvement by pathologists in the investigative process. Their work further encompassed the treating of the perpetrators of crimes who were regarded as mad rather than bad; it is therefore not surprising that by the 1880s, medical officers thought it appropriate to offer opinions about the characteristics of an offender; the earliest of such opinions for which a copy still exists is that offered by the police surgeon Dr. Thomas Bond, in November, 1888, in a letter to Dr. Robert Anderson, head of the London CID, concerning the character of the "Whitechapel murderer".[32] After the murder of Catherine Eddowes, Anderson requested Bond to give his opinion, as significant uncertainty had arisen about the amount of surgical skill and knowledge possessed by the murderer (or murderers). According to investigative psychologist David Canter Dr. Bond's proposals would probably be accepted as thoughtful and intelligent by police forces today.[33] Bond based his assessment on his own examination of the most extensively mutilated victim and the post mortem notes from the four previous murders.

"All five murders no doubt were committed by the same hand. In the first four the throats appear to have been cut from left to right. In the last case, owing to the extensive mutilation it is impossible to say in what direction the fatal cut was made, but arterial blood was found on the wall in splashes close to where the woman's head must have been lying. All the circumstances surrounding the murders lead me to form the opinion that the women must have been lying down when murdered and in every case the throat was first cut."[34]

Dr. Bond was strongly opposed to the idea that the murderer would possess any kind of scientific or anatomical knowledge, or even the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer. In Bond's opinion he must have been a man of solitary habits, subject to "periodical attacks of homicidal and erotic mania"; the character of the mutilations possibly indicating 'satyriasis'. Dr. Bond also stated that "the homicidal impulse may have developed from a revengeful or brooding condition of the mind, or that religious mania may have been the original disease".

Researchers today have continued attempts to profile the killer, drawing parallels with the motives and actions of modern-day serial killers. The timing of the killings at the weekend, and the location of the murders within a few streets of each other, indicate to many that the murderer was employed during the week, and lived locally.[35] The Ripper could have been a deranged schizophrenic, like the "Yorkshire Ripper" Peter Sutcliffe, who heard voices instructing him to attack prostitutes.[36] Alternatively, Stephen Knight suggested in his book Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution that the murders paralled Masonic ritual killings, since the murderers of a legendary masonic figure, Hiram Abiff, were executed by a slash to the throat and disembowelled.[31] Many authors dismiss his theory as a fantasy.[37]

[edit] Letters from the Ripper?

| Jack the Ripper letters |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Over the course of the Ripper murders, the police, newspapers and others received many thousands of letters regarding the case. Some were from well-intentioned persons offering advice for catching the killer. The vast majority of these were deemed useless and subsequently ignored.[38]

Perhaps more interesting were hundreds of letters which claimed to have been written by the killer himself. Nearly all of such letters are considered hoaxes. Many experts contend that none of them are genuine, but of the ones cited as perhaps genuine, either by period or modern authorities, three in particular are prominent:

- The "Dear Boss" letter, dated 25 September, postmarked and received 27 September 1888, by the Central News Agency, was forwarded to Scotland Yard on 29 September. Initially it was considered a hoax, but when Eddowes was found three days after the letter's postmark with one ear partially cut off, the letter's promise to "clip the ladys [sic] ears off" gained attention. Police published the letter on 1 October, hoping someone would recognise the handwriting, but nothing came of this effort. The name "Jack the Ripper" was first used in this letter by the signatory and gained worldwide notoriety after its publication. Most of the letters that followed copied the tone of this one. After the murders, police officials contended the letter had been a hoax by a local journalist.[9] Eddowes' ear appears to have been knicked by the killer incidentally during his attack, and the letter writer's threat to send the ears to the police was never carried out.[39]

- The "Saucy Jacky" postcard, postmarked and received 1 October 1888, by the Central News Agency, had handwriting similar to the "Dear Boss" letter. It mentions that two victims—Stride and Eddowes—were killed very close to one another: "double event this time". It has been argued that the letter was mailed before the murders were publicised, making it unlikely that a crank would have such knowledge of the crime, though it was postmarked more than 24 hours after the killings took place, long after details were known by journalists and residents of the area. Police officials later claimed to have identified a specific journalist as the author of both this message and the earlier "Dear Boss" letter.[40][41]

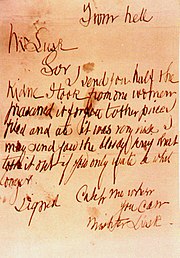

- The "From Hell" letter, also known as the "Lusk letter," postmarked 15 October and received by George Lusk of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee on 16 October 1888. Lusk opened a small box to discover half a human kidney, later said by a doctor to have been preserved in "spirits of wine" (ethanol). One of Eddowes' kidneys had been removed by the killer. The writer claimed that he "fried and ate" the missing kidney half. There is some disagreement over the kidney: some contend it had belonged to Eddowes, while others argue it was "a macabre practical joke, and no more."[42]

Some sources list another letter, dated 17 September 1888, as the first message to use the Jack the Ripper name. Most experts believe this was a modern fake inserted into police records in the 20th century, long after the killings took place.[43] They note that the letter has neither an official police stamp verifying the date it was received nor the initials of the investigator who would have examined it if it were ever considered as potential evidence. It is also not mentioned in any surviving police document of the time.

Ongoing DNA tests on the existant letters have yet to yield conclusive results.[44]

[edit] Media

The Ripper murders mark an important watershed in modern British life. While not the first serial killer, Jack the Ripper's case was the first to create a worldwide media frenzy. Reforms to the Stamp Act in 1855 had enabled the publication of inexpensive newspapers with wider circulation. These mushroomed later in the Victorian era to include mass-circulation newspapers as cheap as a halfpenny, along with popular magazines such as the Illustrated Police News, making the Ripper the beneficiary of previously unparalleled publicity. This, combined with the fact that no one was ever convicted of the murders, created a legend that cast a shadow over later serial killers.

Some believe that the killer's nickname was invented by newspapermen to make for a more interesting story that could sell more papers. This became standard media practice with examples such as the Boston Strangler, the Green River Killer, the Axeman of New Orleans, the Beltway Sniper, and the Hillside Strangler, besides the derivative Yorkshire Ripper almost a hundred years later and the unnamed perpetrator of the "Thames Nude Murders" of the 1960s, whom the press dubbed Jack the Stripper.

The poor of the East End had long been ignored by affluent society, but the nature of the murders and of the victims forcibly drew attention to their living conditions. This attention enabled social reformers of the time to finally gain the support of the "respectable classes." A letter from George Bernard Shaw to the Star newspaper commented sarcastically on these sudden concerns of the press:[45]

| “ | Whilst we Social Democrats were wasting our time on education, agitation and organization, some independent genius has taken the matter in hand, and by simply murdering and disembowelling four women, converted the proprietary press to an inept sort of communism. | ” |

[edit] Suspects

Many theories about the identity and profession of Jack the Ripper have been advanced. None have been entirely persuasive.

[edit] Jack the Ripper in popular culture

Jack the Ripper features in hundreds of works of fiction and non-fiction and works which straddle the boundaries between both fact and fiction: shading into legend. These latter include the Ripper letters, a purported Diary of the Ripper and specimens of poetry alleged to be from the Ripper's own hand. (The Diary has been discredited by experts, including Kenneth Rendell, who, in his analysis, pointed to factual contradictions, handwriting inconsistencies, and anachronistic style.)[46] The Ripper has appeared in novels, short stories, poetry, comic books, video games, songs, plays, films. He even has an 'heroic baritone' singing part in an opera: Lulu by Alban Berg. However, one prominent omission is that, unlike murderers of lesser fame, there is no waxwork figure of him in London's Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussauds, in accordance with Marie Tussaud's original policy of not modelling persons whose likeness is unknown.[47]

One important work of fiction dealing with Jack was written by Robert Bloch in 1943, "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper". In addition to its original hardback publication, the story has been reprinted several times and translated to more than 12 languages. It also inspired numerous other fiction works, including radio, television and theater adaptations, as well as Bloch's own "A Toy for Juliette", dealing with Jack in the future.

To date more than 200 works of non-fiction have been published which deal exclusively with the Jack the Ripper murders,[48] making it one of the most written-about true-crime subjects of the past century. Six periodicals about Jack the Ripper have been introduced since the early 1990s: Ripperana (1992-present), Ripperologist (1994-present, electronic format only since 2005), the Whitechapel Journal (1997–2000), Ripper Notes (1999-present), Ripperoo (2000–2003), and the The Whitechapel Society 1888 Journal (2005-present).[49]

At the time of the murders, a theatrical version of Robert Louis Stevenson's book Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was being performed. The subject matter of horrific murder in the London streets drew much attention, even leading the star of the show to be accused by some members of the public of being the Ripper himself, although this theory was never taken seriously by the police.[50]

One of the more recent films in which the Ripper is a major antagonist is From Hell (2001) based on the graphic novel of the same name by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell, directed by the Hughes Brothers, and starring Johnny Depp as Inspector Abberline, and Heather Graham as Mary Jane Kelly. The film's plot turns on Stephen Knight's conspiracy theory that the murders concealed the birth of an illegitimate royal baby fathered by Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence, and offers Sir William Gull as the murderer.

The legend of the Ripper is still promoted in the East End of London with many guided tours of the murder sites.[7] The Ten Bells, a Victorian pub in Commercial Street that had been frequented by Jack the Ripper's victims, was the focus of such tours for many years. To capitalise on this business, the owners changed its name to the "Jack the Ripper" in the 1960s, but, following protests by feminists and others, the pub returned to its old name.[51]

In 2006, Jack the Ripper was selected by the BBC History Magazine and its readers as the worst Briton in history.[52]

[edit] See also

- Peter Kürten (The Düsseldorf Ripper)

- Dennis Nilsen

- Joseph Vacher (The French Ripper)

- The Blackout Ripper (Gordon Cummins)

- Béla Kiss

- Servant Girl Annihilator

- List of serial killers by number of victims

[edit] References

- ^ FBI's Jack the Ripper web page

- ^ Stewart P. Evans & Keith Skinner (2000), The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Companion ISBN 0786707682

- ^ a b L. Perry Curtis, Jr. (2001) Jack the Ripper and the London Press ISBN 0300088728

- ^ a b c d e Stewart P. Evans & Donald Rumbelow (2006) Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates ISBN 0750942282

- ^ Philip Sugden (1995) The Complete History of Jack the Ripper ISBN 0786702761

- ^ Life and Labour of the People in London (London: Macmillan, 1902-1903) (The Charles Booth on-line archive) accessed 5 August 2008

- ^ a b Donald Rumbelow (2004) The Complete Jack the Ripper ISBN 0140173951

- ^ The Metropolitan Police history of Jack the Ripper

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stewart Evans and Donald Rumbelow (2006) Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates

- ^ Wolf Vanderlinden, "'Considerable Doubt' and the Death of Annie Chapman", Ripper Notes #22, ISBN 0975912933

- ^ Stewart P. Evans & Keith Skinner, The Ultimate Jack The Ripper Sourcebook, pp. 4–7. (citing report by Inspr. Edmund Read, and articles on the Emma Smith inquest, in the Morning Advertiser 9 April 1888 and Lloyds Weekly 8 April 1888.)

- ^ Gerard Spicer, "The Thames Torso Murders of 1887-89"

- ^ Jack the Ripper: A Cast of Thousands

- ^ R. Michael Gordon (2002), "The Thames Torso Murders of Victorian London," McFarland & Company ISBN 9780786413485

- ^ a b Stewart P. Evans & Nicholas Connell (2000), The Man Who Hunted Jack the Ripper ISBN 1902791053

- ^ Reynold's News 29 October 1950, in which Terrence Robinson dubs her Fairy Fay "for want of a better name"

- ^ a b c Paul Begg (2004) Jack the Ripper: The Facts 21-25 ISBN 1861056877

- ^ Her nickname is often mistakenly given as Old Shakespeare, but recent research has shown that it was simply Shakespeare when she was alive. The Old was added years later in a news report that was not using "old" as part of her nickname but as a general descriptor. See [1]

- ^ Wolf Vanderlinden, "The New York Affair" Ripper Notes part one issue 16 (July 2003); part two #17 (January 2004), part three #19 (July 2004 ISBN 0975912909)

- ^ David Canter: Criminal Shadows: Inside the Mind of the Serial Killer, p.12-13. ISBN 0 00 255215 9

- ^ Constable Long's inquest testimony, 11 October 1888, quoted in Marriott, pp.148–149, 153

- ^ John Douglas, Mark Olshaker (2000), The Cases That Haunt Us ISBN 0743212398

- ^ Detective Constable Halse's inquest testimony, 11 October 1888, quoted in Marriott, pp.150–151

- ^ Stewart P. Evans & Keith Skinner: The Ultimate Jack The Ripper Sourcebook, p. 213

- ^ Letter from Charles Warren to the Home Office Undersecretary of State, 6 November 1888, quoted in Marriott, p.159

- ^ Constable Long's inquest testimony, 11 October 1888, quoted in Marriott, p.154

- ^ Philip Sugden, The Complete History of Jack The Ripper, p. 255

- ^ Philip Sugden, The Complete History of Jack The Ripper, p. 254

- ^ Pall Mall Gazette, 1 December 1888 (Casebook Press Project copy).

- ^ Pall Mall Gazette, 6 December 1888 (Casebook Press Project copy).

- ^ a b Stephen Knight (1976) Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution

- ^ David Canter: Criminal Shadows: Inside the Mind of the Serial Killer, pp. 5–6. ISBN 0 00 255215 9

- ^ David Canter: Criminal Shadows: Inside the Mind of the Serial Killer, p. 6. ISBN 0 00 255215 9

- ^ Stewart P. Evans & Keith Skinner: The Ultimate Jack The Ripper Sourcebook, p. 399–402

- ^ Marriott, p.205

- ^ Marriott, p.204

- ^ Begg, pp.x–xi; Marriott, pp.205, 267–268; Rumbelow, pp.209–244

- ^ Stewart Evans and Keith Skinner (2001) Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell

- ^ Marriott, p.221

- ^ Evans and Skinner, Jack the Ripper: Letters From Hell, pp.29–44; Marriott, pp.219–222

- ^ The journalist is identified as Tom Bullen in a letter from Chief Inspector Littlechild to George R. Sims dated 23 September 1913 (quoted in Marriott, p.254)

- ^ DiGrazia, Christopher-Michael (March 2000). "Another Look at the Lusk Kidney". Ripper Notes. http://www.casebook.org/dissertations/dst-cmdlusk.html. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ^ Marriott, p.223

- ^ "Was it Jill the Ripper?" at News.com.au

- ^ Stephen P. Ryder, Public Reactions to Jack the Ripper: Letters to the Editor August - December 1888 (2006) ISBN 0975912976

- ^ Kenneth W. Rendell. Forging History: The Detection of Fake Letters and Documents

- ^ Pauline Chapman (1984) Madame Tussaud's Chamber of Horrors. London, Constable: 96

- ^ Casebook: Jack the Ripper's list of Ripper-specific non-fiction books

- ^ Casebook: Jack the Ripper list of Ripper periodicals

- ^ Martin A. Danahay & Alex Chisholm, Jekyll and Hyde Dramatized (2005) ISBN 0786418702

- ^ William Taylor (2000) This Bright Field: a Travel Book in One Place: 83-92

- ^ "Jack the Ripper is 'worst Briton'" at BBC News

[edit] Additional reading

- Begg, Paul. Jack the Ripper: The Facts. Anova Books, 2006. ISBN 1-86105-687-7.

- Begg, Paul, Martin Fido and Keith Skinner. The Jack the Ripper A-Z. Headline Book Publishing, 1996. ISBN 0-7472-5522-9.

- Curtis, Lewis Perry. Jack The Ripper & The London Press. Yale University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-300-08872-8.

- Evans, Stewart P. and Donald Rumbelow. Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates. Sutton Publishing, Limited, 2006. ISBN 0-7509-4228-2.

- Evans, Stewart P. and Keith Skinner. Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell. Sutton, 2001. ISBN 0-7509-2549-3.

- Evans, Stewart P. and Keith Skinner. The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook. Robinson, 2002. ISBN 0-7867-0768-2.

- Jakubowski, Maxim and Nathan Braund, editors. The Mammoth Book of Jack the Ripper. Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1999. ISBN 0-7867-0626-0.

- Marriott, Trevor (2005). Jack the Ripper: The 21st Century Investigation. London: John Blake. ISBN 1-84454-103-7.

- Odell, Robin. Ripperology. Kent State University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-87338-861-5.

- Rumbelow, Donald. The Complete Jack the Ripper. Berkley Pub Group (Mm), (Revised edition 2005). ISBN 0-425-11869-X.

- Sugden, Philip. The Complete History of Jack the Ripper. Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0-7867-0276-1.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Jack the Ripper |

- Jack the Ripper History A site that looks at the history of the murders and puts them into the social context of the era in which they occurred.

- Casebook: Jack the Ripper has an extensive collection of contemporary newspaper reports related to the murders as well as articles by modern authors.

- The Metropolitan Police history of Jack the Ripper discusses the investigation into the killings.

- The History Channel Website has a two-part video podcast which forms a guided tour of the scenes of Jack the Ripper's crime, placing them in historical context. They are free to download or watch as streaming video.

- The UK National Archives - Jack the Ripper holds images and transcripts of letters claiming to be from Jack the Ripper.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||