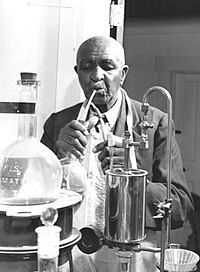

George Washington Carver

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| George Washington Carver | |

|

|

| Born | January 1864[1] Diamond, Missouri, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died | January 5, 1943 (aged 79) Tuskegee, Alabama, U.S. |

George Washington Carver (January 1864[1][2] – January 5, 1943), was an American scientist, botanist, educator, and inventor whose studies and teaching revolutionized agriculture in the Southern United States. The day and year of his birth are unknown; he is believed to have been born before slavery was abolished in Missouri in January 1864.[1]

Much of Carver's fame is based on his research into and promotion of alternative crops to cotton, such as peanuts and sweet potatoes. He wanted poor farmers to grow alternative crops both as a source of their own food and as a source of other products to improve their quality of life. The most popular of his 44 practical bulletins for farmers contained 105 food recipes that used peanuts.[3] He also created or disseminated about 100 products made from peanuts that were useful for the house and farm, including cosmetics, dyes, paints, plastics, gasoline, and nitroglycerin.

In the Reconstruction South, an agricultural monoculture of cotton depleted the soil, and in the early 20th century the boll weevil destroyed much of the cotton crop. Carver's work on peanuts was intended to provide an alternative crop.

In addition to his work on agricultural extension education for purposes of advocacy of sustainable agriculture and appreciation of plants and nature, Carver's important accomplishments also included improvement of racial relations, mentoring children, poetry, painting, and religion. He served as an example of the importance of hard work, a positive attitude, and a good education. His humility, humanitarianism, good nature, frugality, and rejection of economic materialism also have been admired widely.

One of his most important roles was in undermining, through the fame of his achievements and many talents, the widespread stereotype of the time that the black race was intellectually inferior to the white race. In 1941, Time magazine dubbed him a "Black Leonardo", a reference to the white polymath Leonardo da Vinci.[4] To commemorate his life and inventions, George Washington Carver Recognition Day is celebrated on January 5, the anniversary of Carver's death.

Contents |

Early years

Carver was born in Old Calibrator, Newton County, Marion Township, near Crystal Place, now known as Diamond, Missouri, on or around July 12, 1865.[5] His slave owner, Moses Carver, was a German American immigrant who had purchased George's mother, Mary, and father, Giles, from William P. McGinnis on October 9, 1855, for seven hundred dollars. Carver had 10 sisters and a brother, all of whom died prematurely.[citation needed]

George, one of his sisters, and his mother were kidnapped by night raiders and sold in Kentucky, a common practice.[citation needed] Moses Carver hired John Bentley to find them. Only Carver was found, orphaned and near death.[citation needed] Carver's mother and sister had already died, although some reports stated that his mother and sister had gone north with soldiers.[citation needed] For returning George, Moses Carver rewarded Bentley.

After slavery was abolished, Moses Carver and his wife, Susan, raised George and his older brother, James, as their own children.[citation needed] They encouraged George Carver to continue his intellectual pursuits, and "Aunt Susan" taught him the basics of reading and writing.

Since blacks were not allowed at the school in Diamond Grove, and he had received news that there was a school for blacks ten miles (16 km) south in Neosho, he resolved to go there at once. To his dismay, when he reached the town, the school had been closed for the night. As he had nowhere to stay, he slept in a nearby barn. By his own account, the next morning he met a kind woman, Mariah Watkins, from whom he wished to rent a room. When he identified himself as "Carver's George," as he had done his whole life, she replied that from now on his name was "George Carver". George liked this lady very much, and her words, "You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people", made a great impression on him.

At the age of thirteen, due to his desire to attend the academy there, he relocated to the home of another foster family in Fort Scott, Kansas. After witnessing the beating to death of a black man at the hands of a group of white men, George left Fort Scott. He subsequently attended a series of schools before earning his diploma at Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas.

College

Over the next five years, he sent several letters to colleges and was finally accepted at Highland College in Highland, Kansas. He traveled to the college, but he was rejected when they discovered that he was an African American. In August 1886, Carver traveled by wagon with J. F. Beeler from Highland to Eden Township in Ness County, Kansas.[6] He homesteaded a claim[7] near Beeler, where he maintained a small conservatory of plants and flowers and a geological collection. With no help from domestic animals he plowed 17 acres (69,000 m2) of the claim, planting rice, corn, Indian corn and garden produce, as well as various fruit trees, forest trees, and shrubbery. He also did odd jobs in town and worked as a ranch hand.[6]

In early 1888, Carver obtained a $3000 loan at the Bank of Ness City, stating he wanted to further his education, and by June of that year he had left the area.[6]

In 1890, Carver started studying art and piano at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa.[8] His art teacher, Etta Budd, recognized Carver's talent for painting flowers and plants and convinced him to study botany at Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames.[8] He transferred there in 1891, the first black student and later the first black faculty member. In order to avoid confusion with another George Carver in his classes, he began to use the name George Washington Carver.[citation needed]

At the end of his undergraduate career in 1894, recognizing Carver's potential, Joseph Budd and Louis Pammel convinced Carver to stay at Iowa State for his master's degree. Carver then performed research at the Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station under Pammel from 1894 to his graduation in 1896. It is his work at the experiment station in plant pathology and mycology that first gained him national recognition and respect as a botanist.

At Tuskegee with Booker T. Washington

In 1896, Carver was invited to lead the Agriculture Department at the five-year-old Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, later Tuskegee University, by its founder, Booker T. Washington. Carver accepted the position, and remained there for 47 years, teaching former slaves farming techniques for self-sufficiency.

In response to Washington's directive to bring education to farmers, Carver designed a mobile school, called a "Jesup wagon" after the New York financier Morris Ketchum Jesup, who provided funding.[9]

Carver had numerous problems at Tuskegee before he became famous. Carver's perceived arrogance, his higher-than-normal salary and the two rooms he received for his personal use were resented by other faculty.[10] Single faculty members normally bunked two to a room. One of Carver's duties was to administer the Agricultural Experiment Station farms. He was expected to produce and sell farm products to make a profit. He soon proved to be a poor administrator. In 1900, Carver complained that the physical work and the letter-writing his agricultural work required were both too much for him.[11]

In 1902, Booker T. Washington invited Frances Benjamin Johnston, a nationally famous female photographer, to Tuskegee. Carver and Nelson Henry, a Tuskegee graduate, accompanied the attractive white woman to the town of Ramer. Several white citizens thought Henry was improperly associating with a white woman. Someone fired three pistol shots at Henry, and he fled. Mobs prevented him from returning. Carver considered himself fortunate to escape alive.[12]

In 1904, a committee reported that Carver's reports on the poultry yard were exaggerated, and Washington criticized Carver about the exaggerations. Carver replied to Washington "Now to be branded as a liar and party to such hellish deception it is more than I can bear, and if your committee feel that I have willfully lied or [was] party to such lies as were told my resignation is at your disposal."[13] In 1910, Carver submitted a letter of resignation in response to a reorganization of the agriculture programs.[14] Carver again threatened to resign in 1912 over his teaching assignment.[15] Carver submitted a letter of resignation in 1913, with the intention of heading up an experiment station elsewhere.[16] He also threatened to resign in 1913 and 1914 when he didn't get a summer teaching assignment.[17][18] In each case, Washington smoothed things over. It seemed that Carver's wounded pride prompted most of the resignation threats, especially the last two, because he did not need the money from summer work.

In 1911, Washington wrote a lengthy letter to Carver complaining that Carver did not follow orders to plant certain crops at the experiment station.[19] He also refused Carver's demands for a new laboratory and research supplies for Carver's exclusive use and for Carver to teach no classes. He complimented Carver's abilities in teaching and original research but bluntly remarked on his poor administrative skills, "When it comes to the organization of classes, the ability required to secure a properly organized and large school or section of a school, you are wanting in ability. When it comes to the matter of practical farm managing which will secure definite, practical, financial results, you are wanting again in ability." Also in 1911, Carver complained that his laboratory was still without the equipment promised 11 months earlier. At the same time, Carver complained of committees criticizing him and that his "nerves will not stand" any more committee meetings.[20]

Despite their clashes, Booker T. Washington praised Carver in the 1911 book My Larger Education: Being Chapters from My Experience.[21] Washington called Carver "one of the most thoroughly scientific men of the Negro race with whom I am acquainted." Like most later Carver biographies, it also contained exaggerations. It inaccurately claimed that as a young boy Carver "proved to be such a weak and sickly little creature that no attempt was made to put him to work and he was allowed to grow up among chickens and other animals around the servants' quarters, getting his living as best he could." Carver wrote elsewhere that his adoptive parents, the Carvers, were "very kind" to him.[22]

Booker T. Washington died in 1915. His successor made fewer demands on Carver. From 1915 to 1923, Carver's major focus was compiling existing uses and proposing new uses for peanuts, sweet potatoes, pecans, and other crops.[23] This work and especially his promotion of peanuts for the peanut growers association and before Congress eventually made him the most famous African-American of his time.

Rise to fame

Carver had an interest in helping poor Southern farmers who were working low-quality soils that had been depleted of nutrients by repeated plantings of cotton crops. He and other agricultural cognoscenti urged farmers to restore nitrogen to their soils by practicing systematic crop rotation, alternating cotton crops with plantings of sweet potatoes or legumes (such as peanuts, soybeans and cowpeas) that were also sources of protein. Following the crop rotation practice resulted in improved cotton yields and gave farmers new foods and alternative cash crops. In order to train farmers to successfully rotate crops and cultivate the new foods, Carver developed an agricultural extension program for Alabama that was similar to the one at Iowa State. In addition, he founded an industrial research laboratory where he and assistants worked to popularize use of the new plants by developing hundreds of applications for them through original research and also by promoting recipes and applications that they collected from others. Carver distributed his information as agricultural bulletins. (See Carver bulletins below.)

Much of Carver's fame is related to the hundreds of plant products he popularized. After Carver's death, lists were created of the plant products Carver compiled or originated. Such lists enumerate about 300 applications for peanuts and 118 for sweet potatoes, although 73 of the 118 were dyes. He made similar investigations into uses for cowpeas, soybeans, and pecans. Carver did not write down formulas for most of his novel plant products so they could not be made by others. Carver is also credited with the invention of peanut butter.[24]

Until 1921, Carver was not widely known for his agricultural research. However, he was known in Washington, D.C. President Theodore Roosevelt publicly admired his work. James Wilson, a former Iowa state dean and teacher of Carver's, was U.S. secretary of agriculture from 1897 to 1913. Henry Cantwell Wallace, U.S. secretary of agriculture from 1921 to 1924, was one of Carver's teachers at Iowa State. Carver was a friend of Wallace's son, Henry A. Wallace, also an Iowa State graduate.[25] The younger Wallace served as U.S. secretary of agriculture from 1933 to 1940 and as Franklin Delano Roosevelt's vice president from 1941 to 1945.

In 1916 Carver was made a member of the Royal Society of Arts in England, one of only a handful of Americans at that time to receive this honor. However, Carver's promotion of peanuts gained him the most fame.

In 1919, Carver wrote to a peanut company about the great potential he saw for his new peanut milk. Both he and the peanut industry seemed unaware that in 1917 William Melhuish had secured patent #1,243,855 for a milk substitute made from peanuts and soybeans. Despite reservations about his race, the peanut industry invited him as a speaker to their 1920 convention. He discussed "The Possibilities of the Peanut" and exhibited 145 peanut products.

By 1920, U.S. peanut farmers were being undercut with imported peanuts from the Republic of China. White peanut farmers and processors came together in 1921 to plead their cause before a Congressional committee hearings on a tariff. Having already spoken on the subject at the convention of the United Peanut Associations of America, Carver was elected to speak in favor of a peanut tariff before the Ways and Means Committee of the United States House of Representatives. Carver was a novel choice because of U.S. racial segregation. On arrival, Carver was mocked by surprised Southern congressmen, but he was not deterred and began to explain some of the many uses for the peanut. Initially given ten minutes to present, the now spellbound committee extended his time again and again. The committee rose in applause as he finished his presentation, and the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922 included a tariff on imported peanuts. Carver's presentation to Congress made him famous, while his intelligence, eloquence, amiability, and courtesy delighted the general public.

Life while famous

During the last two decades of his life, Carver seemed to enjoy his celebrity status. He was often to be found on the road promoting Tuskegee, peanuts, and racial harmony. Although he only published six agricultural bulletins after 1922, he published articles in peanut industry journals and wrote a syndicated newspaper column, "Professor Carver's Advice". Business leaders came to seek his help, and he often responded with free advice. Three American presidents—Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge and Franklin Roosevelt—met with him, and the Crown Prince of Sweden studied with him for three weeks.

In 1923, Carver received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP, awarded annually for outstanding achievement. From 1923 to 1933, Carver toured white Southern colleges for the Commission on Interracial Cooperation.[23]

Carver was famously criticized in the November 20, 1924, New York Times article "Men of Science Never Talk That Way." The Times considered Carver's statements that God guided his research inconsistent with a scientific approach. The criticism garnered much sympathy for Carver, as many Christians viewed it as an attack on religion.

In 1928, Simpson College bestowed on Carver an honorary doctorate. For a 1929 book on Carver, Raleigh H. Merritt contacted him. Merritt wrote "At present not a great deal has been done to utilize Dr. Carver's discoveries commercially. He says that he is merely scratching the surface of scientific investigations of the possibilities of the peanut and other Southern products."[26] Yet, in 1932 professor of literature James Saxon Childers wrote that Carver and his peanut products were almost solely responsible for the rise in U.S. peanut production after the boll weevil devastated the American cotton crop beginning about 1892. Childer's 1932 article on Carver, "A Boy Who Was Traded for a Horse", in The American Magazine, and its 1937 reprint in Reader's Digest, did much to establish this Carver myth. Other major magazines and newspapers of the time also exaggerated Carver's impact on the peanut industry.[27]

From 1933 to 1935, Carver was largely occupied with work on peanut oil massages for treating infantile paralysis (polio).[23] Carver received tremendous media attention and visitations from parents and their sick children; however, it was ultimately found that peanut oil was not the miracle cure it was made out to be—it was the massages which provided the benefits. Carver had been a trainer for the Iowa State football team and was skilled as a masseur. From 1935 to 1937, Carver participated in the USDA Disease Survey. Carver had specialized in plant diseases and mycology for his master's degree.

In 1937, Carver attended two chemurgy conferences.[23] He met Henry Ford at the Dearborn, Michigan, conference, and they became close friends. Also in 1937, Carver's health declined. Time magazine reported in 1941 that Henry Ford installed an elevator for Carver because his doctor told him not to climb the 19 stairs to his room.[4] In 1942, the two men denied that they were working together on a solution to the wartime rubber shortage. Carver also did work with soy, which he and Ford considered as an alternative fuel.

In 1939, Carver received the Roosevelt Medal for Outstanding Contribution to Southern Agriculture enscribed "to a scientist humbly seeking the guidance of God and a liberator to men of the white race as well as the black." In 1940, Carver established the George Washington Carver Foundation at the Tuskegee Institute. In 1941, The George Washington Carver Museum was dedicated at the Tuskegee Institute. In 1942, Henry Ford built a replica of Carver's slave cabin at the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in Dearborn as a tribute to his friend. Also in 1942, Ford dedicated the George Washington Carver Laboratory in Dearborn.

Death and afterwards

Upon returning home one day, Carver took a bad fall down a flight of stairs; he was found unconscious by a maid who took him to a hospital. Carver died January 5, 1943, at the age of 78 from complications (anemia) resulting from this fall. He was buried next to Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee University. Due to his frugality, Carver's life savings totaled $60,000, all of which he donated in his last years and at his death to the Carver Museum and to the George Washington Carver Foundation.[28]

On his grave was written the simplest and most meaningful summary of his life. He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.

Before and after his death, there was a movement to establish a U.S. national monument to Carver. However, because of World War II such non-war expenditures were banned by presidential order. Missouri senator Harry S Truman sponsored a bill anyway. In a committee hearing on the bill, one supporter argued that "The bill is not simply a momentary pause on the part of busy men engaged in the conduct of the war, to do honor to one of the truly great Americans of this country, but it is in essence a blow against the Axis, it is in essence a war measure in the sense that it will further unleash and release the energies of roughly 15,000,000 Negro people in this country for full support of our war effort."[23] The bill passed in both houses without a single vote against.

On July 14, 1943,[29] President Franklin Delano Roosevelt dedicated $30,000 for the George Washington Carver National Monument west-southwest of Diamond, Missouri—an area where Carver had spent time in his childhood. This was the first national monument dedicated to an African-American and also the first to a non-President. At this 210-acre (0.8 km2) national monument, there is a bust of Carver, a ¾-mile nature trail, a museum, the 1881 Moses Carver house, and the Carver cemetery. Due to a variety of delays, the national monument was not opened until July, 1953.

In December 1947, a fire destroyed all but three of 48 of Carver's paintings at the Carver Museum [30] Carver appeared on U.S. commemorative stamps in 1948 and 1998, and he was depicted on a commemorative half dollar coin from 1951 to 1954. Two ships, the Liberty ship SS George Washington Carver and the nuclear submarine USS George Washington Carver (SSBN-656) were named in his honor.

In 1977, Carver was elected to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans. In 1990, Carver was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. In 1994, Iowa State University awarded Carver Doctor of Humane Letters. In 2000, Carver was a charter inductee in the USDA Hall of Heroes as the "Father of Chemurgy".[31]

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed George Washington Carver on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[32]

In 2005, Carver's research at the Tuskegee Institute was designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark by the American Chemical Society.[33] On February 15, 2005, an episode of Modern Marvels included scenes from within Iowa State University's Food Sciences Building and about Carver's work. In 2005, the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis, Missouri, opened a George Washington Carver garden in his honor, which includes a lifesize statue of him.

Many institutions honor George Washington Carver to this day, particularly the American public school system. Dozens of elementary schools and high schools are named after him. National Basketball Association star David Robinson and his wife, Valerie, founded an academy named after Carver; it opened on September 17, 2001, in San Antonio, Texas.[34]

Reputed inventions

George Washington Carver reputedly discovered three hundred uses for peanuts and hundreds more for soybeans, pecans and sweet potatoes. Among the listed items that he suggested to southern farmers to help them economically were adhesives, axle grease, bleach, buttermilk, chili sauce, fuel briquettes(a biofuel), ink, instant coffee, linoleum, mayonnaise, meat tenderizer, metal polish, paper, plastic, pavement, shaving cream, shoe polish, synthetic rubber, talcum powder and wood stain. Three patents (one for cosmetics, and two for paints and stains) were issued to George Washington Carver in the years 1925 to 1927; however, they were not commercially successful in the end. Aside from these patents and some recipes for food, he left no formulae or procedures for making his products.[35] He did not keep a laboratory notebook.

It is a common misconception that Carver's research on products that could be made by small farmers for their own use led to commercial successes that revolutionized Southern agriculture,[36][37] but these products were intended as adequate replacements for commercial products that were outside the budget of the small one-horse farmer. Carver's work to apply the scientific method to sustain small farmers and to provide them with the resources to be as independent of the cash economy as possible foreshadowed the "appropriate technology" work of E.F. Schumacher.

Peanut products

Dennis Keeney, director of the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University, wrote in the Leopold Letter newsletter:

Carver worked on improving soils, growing crops with low inputs, and using species that fixed nitrogen (hence, the work on the cowpea and the peanut). Carver wrote in The Need of Scientific Agriculture in the South: "The virgin fertility of our soils and the vast amount of unskilled labor have been more of a curse than a blessing to agriculture. This exhaustive system for cultivation, the destruction of forest, the rapid and almost constant decomposition of organic matter, have made our agricultural problem one requiring more brains than of the North, East or West.

(Information taken from Fishbein, Toby. "The legacy of George Washington Carver." http://lib.iastate.edu/spcl/gwc/bio.html)

Carver did market a few of his peanut products. The Carver Penol Company sold a mixture of creosote and peanuts as a patent medicine for respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis. Other ventures were The Carver Products Company and the Carvoline Company. Carvoline Antiseptic Hair Dressing was a mix of peanut oil and lanolin. Carvoline Rubbing Oil was a peanut oil for massages.

Sweet potato products

Next to peanuts, Carver is most associated with sweet potato products. In his 1922 sweet potato bulletin Carver listed a few dozen recipes "many of which I have copied verbatim from Bulletin No. 129, U. S. Department of Agriculture".[38]

The list of Carver's sweet potato inventions compiled from Carver's records includes 73 dyes, 17 wood fillers, 14 candies, 5 library pastes, 5 breakfast foods, 4 starches, 4 flours, and 3 molasseses.[39] There are also listings for vinegar and spiced vinegar, dry coffee and instant coffee, candy, after-dinner mints, orange drops, and lemon drops.

Carver bulletins

During his more than four decades at Tuskegee, Carver's official published work consisted mainly of 44 practical bulletins for farmers.[40] His first bulletin in 1898 was on feeding acorns to farm animals. His final bulletin in 1943 was about the peanut. He also published six bulletins on sweet potatoes, five on cotton, and four on cowpeas. Some other individual bulletins dealt with alfalfa, wild plum, tomato, ornamental plants, corn, poultry, dairying, hogs, preserving meats in hot weather, and nature study in schools.

His most popular bulletin, How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption, was first published in 1916[3] and was reprinted many times. It gave a short overview of peanut crop production and contained a list of recipes from other agricultural bulletins, cookbooks, magazines, and newspapers, such as the Peerless Cookbook, Good Housekeeping, and Berry's Fruit Recipes. Carver's was far from the first American agricultural bulletin devoted to peanuts,[41][42][43][44][45] but his bulletins did seem to be more popular and widespread than previous ones.

Religion

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until the dispute is resolved. (March 2009) |

While George Washington Carver is most widely recognized for his scientific contributions regarding the peanut, he is also often recognized as a devoted Christian. God and science were both areas of interest, not warring ideas in the mind of George Washington Carver. He testified on many occasions that his faith in Jesus was the only mechanism by which he could effectively pursue and perform the art of science.[46][47]

George Washington Carver became a Christian when he was ten years old. He matured in his faith by placing his understanding of God firmly in the words of the Bible.[48][49] When he was still a young boy, he was not expected to live past his twenty-first birthday due to conspicuously failing health. He used the prognosis as an opportunity to exercise his trust in God and pushed forward. He lived well past the age of twenty-one, and his trust in God's provision deepened as a result.[22] Throughout his career, he always found friendship and safety in the fellowship of other Christians. He relied on them exceedingly when enduring harsh criticism from the scientific community and newsprint media regarding his research methodology.[50]

Dr. Carver's faith was foundational in how he approached life. He viewed faith in Jesus as a means to destroying both barriers of racial disharmony and social stratification.[51] For Dr. Carver, faith was an agent of change. It increased knowledge rather than competing against it. The greater his faith increased, the more he desired to learn. The more he learned, the greater his faith became.[52] In attempts to teach his students, he defaulted first and foremost to the proclamation of Christ. He taught that knowledge of God through the Bible and devotion to Jesus were paramount to what he could teach them pedagogically through numbers and formulas.[53] He was as concerned with his students' character development as he was with their intellectual development. He even compiled a list of eight cardinal virtues for his students to emulate and strive toward:

- Be clean both inside and out.

- Neither look up to the rich or down on the poor.

- Lose, if need be, without squealing.

- Win without bragging.

- Always be considerate of women, children, and older people.

- Be too brave to lie.

- Be too generous to cheat.

- Take your share of the world and let others take theirs.[34]

Carver also led a Bible class on Sundays while at Tuskegee, beginning in 1906, for several students at their request. In this class he would regularly tell the stories from the Bible by acting them out.[34] Unconventional in respect to both his scientific method and his ambition as a teacher, he inspired as much criticism as he did praise.[54] Dr. Carver expressed this sentiment in response to this phenomenon: "When you do the common things in life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world."[55]

The legacy of George Washington Carver's faith is included in many Christian book series for children and adults about great men and women of faith and the work they accomplished through their convictions respectively. One such series, the Sower series, includes his story alongside those of such men as Isaac Newton, Samuel Morse, Johannes Kepler, and the Wright brothers.[56] Other Christian literary references include "Man’s Slave, God’s Scientist", by David R. Collins and the Heroes of the Faith series book "George Washington Carver: Inventor and Naturalist" by Sam Wellman. He is also included in Christian and homeschooling curricula in the history units along with Abraham Lincoln, David Livingstone, and Eric Liddell.

Notes

- ^ a b c "About GWC: A Tour of His Life". George Washington Carver National Monument. National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/archive/gwca/expanded/gwc_tour_01.htm. "George Washington Carver did not know the exact date of his birth, but he thought it was in January 1864 (some evidence indicates July 1861, but not conclusively). He knew it was sometime before slavery was abolished in Missouri, which occurred in January 1864."

- ^ The Notable Names Database cites July 12, 1864 as Carver's birthday here.

- ^ a b Carver, George Washington. 1916. How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption. Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin 31.

- ^ a b "Black Leonardo Book". Time Magazine. 1941-11-24. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,801330,00.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-10.

- ^ Pages 9-10 of George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol by Linda McMurry, 1982. New York: Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-503205-5)

- ^ a b c George Washington Carver: Scientist, Scholar, and Educator from the "Blue Skyways" website of the Kansas State Library

- ^ Southeast Quarter of Section 4, Township 19 South, Range 26 West of the Sixth Principal Meridian, Ness County, Kansas

- ^ a b College Archives - George Washington Carver from the Simpson College website

- ^ The first Jesup Wagon from a National Park Service website

- ^ Pages 45-47 of McMurry

- ^ Volume 5, page 481 of Harlan

- ^ Volume 5, page 504 of Harlan

- ^ Volume 8, page 95 of Harlan

- ^ Volume 10, page 480 of Harlan

- ^ Volume 12, page 95 of Harlan

- ^ Volume 12, pages 251-252 of Harlan

- ^ Volume 12, page 201 of Harlan

- ^ Volume 13, page 35 of Harlan

- ^ Volume 10, pages 592-596 of Harlan

- ^ Volume 4, page 239 of Harlan

- ^ Booker T. Washington, 1856-1915 My Larger Education: Being Chapters from My Experience

- ^ a b GWC | His Life in his own words

- ^ a b c d e Special History Study from the National Park Service website

- ^ The History of Peanut Butter

- ^ The legacy of George Washington Carver-Friends & Colleagues (Henry Wallace

- ^ Raleigh Howard Merritt. From Captivity to Fame or The Life of George Washington Carver

- ^ "Peanut Man". Time Magazine. 1937-06-14. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,757923-1,00.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-10.

- ^ GWC | Tour Of His Life |Page 6

- ^ George Washington Carver National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)

- ^ "Change Without Revolution". Time Magazine. 1948-01-05. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,794072,00.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-10.

- ^ USDA Hall of Heroes

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ^ George Washington Carver: Chemist, Teacher, Symbol

- ^ a b c History from the Carver Academy website

- ^ Mackintosh, Barry. 1977. George Washington Carver and the Peanut: New Light on a Much-loved Myth. American Heritage 28(5): 66-73.

- ^ McMurry, L.O. 1981. George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol. New York, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Smith, Andrew F. 2002. Peanuts: The Illustrious History of the Goober Pea. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- ^ How the Farmer Can Save His Sweet Potatoes, Geo. W. Carver from the Texas A&M University website

- ^ Carver Sweet Potato Products from the Tuskegee University website

- ^ List of Bulletins by George Washington Carver from the Tuskegee University website

- ^ Handy, R.B. 1895. Peanuts: Culture and Uses. USDA Farmers' Bulletin 25.

- ^ Newman, C.L. 1904. Peanuts. Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

- ^ Beattie, W.R. 1909. Peanuts. USDA Farmers' Bulletin 356.

- ^ Ferris, E.B. 1909. Peanuts. Agricultural College, Mississippi: Mississippi Agricultural Experiment Station.

- ^ Beattie, W.R. 1911. The Peanut. USDA Farmers' Bulletin 431.

- ^ Man of science-and of God from The New American (January, 2004) via AccessMyLibrary

- ^ George Washington Carver from CreationWiki, the encyclopedia of creation science

- ^ George Washington Carver: Pocket Watch and Bible from a National Park Service website

- ^ http://www.mhmin.org/FC/fc-1293GeorgeC.htm

- ^ http://www.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/n/Newman,Wilson_L.

- ^ Quotes From Dr. Carver | Page 2 from a National Park Service website

- ^ Legends of Tuskegee: George Washington Carver-From Slave to Student from a National Park Service website

- ^ The Educational Theory of George Washington Carver from newfoundations.com

- ^ George Washington Carver

- ^ George Washington Carver Quotes

- ^ Whole Life Stewardship - Books

- ^ Brummitt RK; Powell CE. (1992). Authors of Plant Names. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 1-84246-085-4.

References

- Carver, George Washington. "1897 or Thereabouts: George Washington Carver's Own Brief History of His Life." George Washington Carver National Monument.

- Kremer, Gary R. (editor). 1987. George Washington Carver in His Own Words. Columbia, Missouri.: University of Missouri Press.

- McMurry, L. O. Carver, George Washington. American National Biography Online Feb. 2000

- George Washington Carver : Man’s Slave, God’s Scientist, Collins, David R., Mott Media, 1981)

- George Washington Carver: His Life & Faith in His Own Words (Hardcover) by William J. Federer Publisher: AmeriSearch (January 2003) ISBN-10: 0965355764

- George Washington Carver: In His Own Words (Paperback)by George W. Carver Publisher: University of Missouri Press; Reprint edition (January 1991) ISBN-10: 0826207855 ISBN-13: 978-0826207852

- H.M. Morris, Men of Science, Men of God (1982)

- E.C.Barnett & D.Fisher, Scientists Who Believe (1984)

- G.R. Kremer, George Washington Carver in His Own Words (1987)

See also

- African-American history

- Boll Weevil

- Carver Academy

- List of people on stamps of the United States

- Peanut

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: George Washington Carver |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: George Washington Carver |

- Carver Tribute from Tuskegee University

- Iowa State University, The Legacy of George Washington Carver from Iowa State University

- National Historic Chemical Landmark from the American Chemical Society

- George Washington Carver at Find A Grave

Print publications

- George Washington Carver. "How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption", Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin 31

- George Washington Carver. "How the Farmer Can Save His Sweet Potatoes and Ways of Preparing Them for the Table," Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin 38, 1936.

- George Washington Carver. "How to Grow the Tomato and 115 Ways to Prepare it for the Table" Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin 36, 1936.

- Peter D. Burchard, "George Washington Carver: For His Time and Ours," National Parks Service: George Washington Carver National Monument. 2006.

- Louis R. Harlan, Ed., The Booker T. Washington Papers, Volume 4, pp. 127-128. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. 1975.

- Mark Hersey, "Hints and Suggestions to Farmers: George Washington Carver and Rural Conservation in the South," Environmental History April 2006

- Barry Mackintosh, "George Washington Carver and the Peanut: New Light on a Much-loved Myth," American Heritage 28(5): 66-73, 1977.

- Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol, New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. (Questia Online Library: here, Google Books:here)

- Raleigh H. Merritt, From Captivity to Fame or the Life of George Washington Carver, Boston: Meador Publishing. 1929.

- George Washington Carver

|

||||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Carver, George Washington |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | botanist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1864 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Diamond, Missouri, United States of America |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 5, 1943 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Tuskegee, Alabama, United States of America |