Shakespeare's sonnets

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Shakespeare's sonnets, or simply The Sonnets, is a collection of poems in sonnet form written by William Shakespeare that deal with such themes as love, beauty, politics, and mortality. They were probably written over a period of several years. All 154 poems appeared in a 1609 collection, entitled SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS, comprising 152 previously unpublished sonnets and two (numbers 138 and 144) that had previously been published in a 1599 miscellany entitled The Passionate Pilgrim.

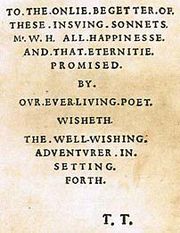

The Sonnets were published under conditions that have become unclear to history. Although the works were written by Shakespeare, it is not known if the publisher, believed to be Thomas Thorpe,[1] used an authorized manuscript from him, or an unauthorized copy. Also, there is a mysterious dedication at the beginning of the text wherein a certain "Mr. W.H." is described by the publisher as "the onlie begetter" of the poems, but it is not known who this man was. In addition, several aspects of The Sonnets have been noted in the ongoing Shakespeare authorship question.

The first 17 sonnets are written to a young man, urging him to marry and have children,[2] thereby passing down his beauty to the next generation. These are called the procreation sonnets. Most of them, however, 18-126, are addressed to a young man expressing the poet's love for him. Sonnets 127-152 are written to the poet's mistress expressing his strong love for her. The final two sonnets, 153-154, are allegorical. The final thirty or so sonnets are written about a number of issues, such as the young man's infidelity with the poet's mistress, self-resolution to control his own lust, beleaguered criticism of the world, etc.

Contents |

[edit] Dedication to Mr. W.H.

The only edition of the sonnets published in Shakespeare's lifetime, the 1609 Quarto, is dedicated to one "Mr. W.H.". The reality, identity and age of this person remain a mystery and have caused a great deal of speculation.

The dedication in full reads:

| “ |

TO.THE.ONLIE.BEGETTER.OF. |

” |

While it is generally believed that 'T.T.' stands for the publisher, Thomas Thorpe,[citation needed] it is not certain whether Thorpe, Shakespeare, or another editor wrote the dedication. The capital letters and periods following each word were probably intended to resemble an Ancient Roman inscription, thereby giving a sense of eternity and magnitude to the sonnets. In the sonnets, Shakespeare often declares that the sonnets will outlast such earthly things as stone monuments and inscriptions.[3] Sonnet 55 states,

- Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

- Of princes shall outlive this pow'rful rhyme,

126 of Shakespeare's sonnets are addressed to a young man (often called the "Fair Youth"). Broadly speaking, there are two branches of theories concerning the identity of Mr. W.H.[citation needed]: those that take him to be identical to the youth, and those that assert him to be a separate person.

The following is a non-exhaustive list of contenders:

- William Herbert (the Earl of Pembroke). Herbert is seen by many as the most likely candidate, since he was also the dedicatee of the First Folio of Shakespeare's works. Note, however, that lords are never addressed as "Mr.".[citation needed]

- Henry Wriothesley (the Earl of Southampton). Many have argued that 'W.H.' is Southampton's initials reversed, and that he is a likely candidate as he was the dedicatee of Shakespeare's poems Venus & Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. Southampton was also known for his good looks, and has often been argued to be the 'fair youth' of the sonnets. But note again that lords are never addressed as "Mr.".[citation needed]

- Sir William Harvey, Southampton's stepfather. This theory assumes that the fair youth and Mr. W.H. are separate people, and that Southampton is the fair youth. Harvey would be the "begetter" of the Sonnets in the sense that it would be he who provided them to the publisher.[citation needed]

- William Himself (i.e. Shakespeare). This theory was proposed by the German scholar D. Barnstorff, but has not found much support.[citation needed]

- A simple printing error for Shakespeare's initials, 'W.S.' or 'W. Sh'. This was suggested by Bertrand Russell in his memoirs, and also by Don Foster in "Master W.H., R.I.P." (PMLA 102, pp. 42-54) and by Jonathan Bate in The Genius of Shakespeare. Bate supports his point by reading 'onlie' as something like 'peerless', 'singular' and 'begetter' as 'maker', ie. 'writer'. The phrase 'Our Ever-Living Poet', according to Foster, refers to God, not Shakespeare. 'Poet' comes from the Greek 'poetes' which means 'maker', a fact remarked upon in various contemporary texts; also, in Elizabethan English the word 'maker' was used to mean 'poet'. These researcher believe the phrase 'our ever-living poet' might easily have been taken to mean 'our immortal maker' (God). The 'eternity' promised us by our immortal maker would then be the eternal life that is promised us by God, and the dedication would conform with the standard formula of the time, according to which one person wished another 'happiness [in this life] and eternal bliss [in heaven]'. Shakespeare himself, on this reading, is 'Mr. W. [S]H.' the 'onlie begetter', i.e., the sole author, of the sonnets, and the dedication is advertising the authenticity of the poems.

- William Hall. Hall was a printer who had been responsible for printing other work that Thorpe had published (according to this theory, the dedication is simply Thorpe's tribute to his colleague and has nothing to do with Shakespeare). This theory, started by Sir Sidney Lee in his A Life of William Shakespeare (1898), was continued by Colonel B.R. Ward in his The Mystery of Mr. W.H. (1923). Supporters of this theory point out that the full name "William Hall" appears if the word "all", immediately following the initials in the dedication, is added to them. Under his initials, William Hall had edited a collection of the poems of Robert Southwell that was published by George Eld, Thorpe's printer for the Sonnets volume.[4] There is also documentary evidence of one William Hall of Hackney who signed himself 'WH' three years earlier, but it is not certain that this was the same man as the printer.

- Willie Hughes. The 18th century scholar Thomas Tyrwhitt first proposed the theory that the Mr. W.H. (and the Fair Youth) was one "William Hughes", based on presumed puns on the name in the sonnets. The argument was repeated in Edmund Malone's 1790 edition of the sonnets. The most famous exposition of the theory is in Oscar Wilde's short story "The Portrait of Mr. W.H.", in which Wilde, or rather the story's narrator, describes the puns on "will" and "hues" in the sonnets, and argues that they were written to a seductive young actor named Willie Hughes who played female roles in Shakespeare's plays. There is no evidence for the existence of any such person.

- William Haughton, a contemporary dramatist.[citation needed]

- William Hart, Shakespeare's nephew and male heir. Hart was an actor himself and never married.[citation needed]

In his 2002 Oxford Shakespeare edition of the sonnets, Colin Burrow argues that the dedication is deliberately mysterious and ambiguous, possibly standing for "Who He", a conceit also used in a contemporary pamphlet. He suggests that it may have been created by Thorpe simply to encourage speculation and discussion (and hence, sales of the text). [5]

[edit] Shakespeare Authorship question

Several aspects of The Sonnets have been noted in the ongoing Shakespeare authorship question: The dedication refers to the poet as "Ever-Living", a phrase which has helped fuel the authorship debate due to its use as an epithet for the deceased (Shakespeare himself used the phrase in this way in Henry VI, part 1 (IV, iii, 51-2) describing the dead Henry V as “[t]hat ever-living man of memory”). Authorship proponents believe this phrase indicates that the real author of the sonnets was dead by 1609, whereas Shakespeare of Stratford lived until 1616.[6] Adding further to the authorship debate, Shakespeare's name is hyphenated on the title page and on the top of every other page in the book. Authorship proponents have noted that hyphenation was often used to indicate a pseudonym.

[edit] Structure

The sonnets are almost all constructed from three four-line stanzas (called quatrains) and a final couplet composed in iambic pentameter[7] (a meter used extensively in Shakespeare's plays) with the rhyme scheme abab cdcd efef gg (this form is now known as the Shakespearean sonnet). The only exceptions are Sonnets 99, 126, and 145. Number 99 has fifteen lines. Number 126 consists of six couplets, and two blank lines marked with italic brackets; 145 is in iambic tetrameters, not pentameters. Often, the beginning of the third quatrain marks the volta ("turn"), or the line in which the mood of the poem shifts, and the poet expresses a revelation or epiphany.

There is another variation on the standard English structure, found for example in sonnet 29. The normal rhyme scheme is changed by repeating the b of quatrain one in quatrain three where the f should be. This leaves the sonnet distinct between both English and Spenserian styles.

| “ | When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes I all alone beweep my outcast state, |

” |

Whether the author intended to step over the boundaries of the standard rhyme scheme will always be in question. Some, like Sir Denis Bray, find the repetition of the words and rhymes to be a "serious technical blemish"[8], while others, like Kenneth Muir, think "the double use of 'state' as a rhyme may be justified, in order to bring out the stark contrast between the Poet's apparently outcast state and the state of joy described in the third quatrain."[9] Given that this is the only sonnet in the collection that follows this pattern, its hard to say if it was purposely done. But most of the poets at the time were well educated; "schooled to be sensitive to variations in sounds and word order that strike us today as remarkably, perhaps even excessively, subtle." [10] Shakespeare must have been well aware of this subtle change to the firm structure of the English sonnets.

[edit] Characters

Readers of the sonnets today commonly refer to these characters as the Fair Youth, the Rival Poet, and the Dark Lady. The narrator expresses admiration for the Fair Youth's beauty, and later has an affair with the Dark Lady. It is not known whether the poems and their characters are fiction or autobiographical. If they are autobiographical, the identities of the characters are open to debate. Various scholars, most notably A. L. Rowse, have attempted to identify the characters with historical individuals.[citation needed]

[edit] Fair Youth

The 'Fair Youth' is an unnamed young man to whom sonnets 1-126 are addressed. The poet writes of the young man in romantic and loving language, a fact which has led several commentators to suggest a homosexual relationship between them, while others read it as platonic love.

The earliest poems in the collection do not imply a close personal relationship; instead, they recommend the benefits of marriage and children. With the famous sonnet 18 ("Shall I compare thee to a summer's day") the tone changes dramatically towards romantic intimacy. Sonnet 20 explicitly laments that the young man is not a woman. Most of the subsequent sonnets describe the ups and downs of the relationship, culminating with an affair between the poet and the Dark Lady. The relationship seems to end when the Fair Youth succumbs to the Lady's charms.

There have been many attempts to identify the Friend. Shakespeare's one-time patron, the Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton is the most commonly suggested candidate,[citation needed] although Shakespeare's later patron, William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, has recently become popular [1]. Both claims have much to do with the dedication of the sonnets to 'Mr. W.H.', "the only begetter of these ensuing sonnets": the initials could apply to either Earl. However, while Shakespeare's language often seems to imply that the 'friend' is of higher social status than himself, this may not be the case. The apparent references to the poet's inferiority may simply be part of the rhetoric of romantic submission. An alternative theory, most famously espoused by Oscar Wilde's short story 'The Portrait of Mr. W.H.' notes a series of puns that may suggest the sonnets are written to a boy actor called William Hughes; however, Wilde's story acknowledges that there is no evidence for such a person's existence. Samuel Butler believed that the friend was a seaman, and recently Joseph Pequigney ('Such Is My love') an unknown commoner.

[edit] The Dark Lady

Sonnets 127-152 are addressed to a woman commonly known as the 'Dark Lady' because her hair is said to be black and her skin "dun". These sonnets are explicitly sexual in character, in contrast to those written to the "Fair Youth". It is implied that the speaker of the sonnets and the Lady had a passionate affair, but that she was unfaithful, perhaps with the "Fair Youth". The poet self-deprecatingly describes himself as balding and middle-aged at the time of writing.

Many attempts have been made to identify the "Dark Lady" with historical personalities, such as Mary Fitton or the poet Emilia Lanier, who was Rowse's favoured candidate, though neither lady fits the author's descriptions.[citation needed] She has also been identified with Elizabeth Wriothesley, Countess of Southampton.[2]

Some readers have suggested that the reference to her "dun" (a dull, grayish, brown color) skin and "black wires...on her head" suggests that she was of African descent, as the trait described is uniquely African (as referenced in Anthony Burgess's novel about Shakespeare, Nothing Like the Sun). Others, however, maintain that the Dark Lady is merely a fictional character who never really existed in real life; they suggest that the "darkness" of the lady is not intended literally, but rather represents the "dark" forces of physical lust as opposed to the ideal Platonic love associated with the "Fair Youth". Some have identified her with Hermia in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, who is also described as dark-haired.

William Wordsworth was unimpressed by these sonnets. He wrote that,

These sonnets, beginning at 127, to his Mistress, are worse than a puzzle-peg. They are abominably harsh, obscure & worthless. The others are for the most part much better, have many fine lines, very fine lines & passages. They are also in many places warm with passion. Their chief faults, and heavy ones they are, are sameness, tediousness, quaintness, & elaborate obscurity.

[edit] The Rival Poet

The Rival Poet is sometimes identified with Christopher Marlowe or George Chapman.[citation needed] However, there is no hard evidence that the character had a real-life counterpart. The Poet sees the Rival as competition for fame and patronage. The sonnets most commonly identified as The Rival Poet group exist within the Fair Youth series in sonnets 78-86.[11]

[edit] Themes

One interpretation is that Shakespeare's Sonnets are in part a pastiche or parody of the three centuries-long tradition of Petrarchan love sonnets; in them, Shakespeare consciously inverts conventional gender roles as delineated in Petrarchan sonnets to create a more complex and potentially troubling depiction of human love.[12] Shakespeare also violated many sonnet rules which had been strictly obeyed by his fellow poets: he speaks on human evils that do not have to do with love (66), he comments on political events (124), he makes fun of love (128), he parodies beauty (130), he plays with gender roles (20), he speaks openly about sex (129) and even introduces witty pornography (151).

[edit] Legacy

Coming as they do at the end of conventional Petrarchan sonneteering, Shakespeare's sonnets can also be seen as a prototype, or even the beginning, of a new kind of 'modern' love poetry. During the eighteenth century, their reputation in England was relatively low; as late as 1805, The Critical Review could still credit Milton with the perfection of the English sonnet. As part of the renewed interest in Shakespeare's original work that accompanied Romanticism, the sonnets rose steadily in reputation during the nineteenth century.[13]

The outstanding cross-cultural importance and influence of the sonnets is demonstrated by the large number of translations that have been made of them. To date in the German-speaking countries alone, there have been 70 complete translations since 1784. There is no major written language into which the sonnets have not been translated, including Latin,[14] Turkish, Japanese, Esperanto,[15] and even Klingon.[16]

The sonnets are often referenced in popular culture. For example in a 2007 episode of Doctor Who, entitled The Shakespeare Code, Shakespeare began a good-bye to Martha Jones in the form of Sonnet 18, referring to her as his dark lady. This is intended to indicate that Martha is the famed Dark Lady from these sonnets.

[edit] Principal audio and audio-visual interpretations

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2008) |

Complete audio recordings of all the 154 Sonnets by individual readers are quite scarce. Probably the best known purely audio interpretation of a near-complete collection is that by the legendary British actor, Sir John Gielgud (Caedmon 1963). Another memorable version is that by the English-born screen actor Ronald Colman (multi LP set, date unreported). More recent unabridged recordings have been made by the British actor Simon Callow (HighBridge Co. Oct 2005). The American film actor Stacy Keach has also recently offered his interpretation in a 2 cd set (label unspecified). Other individual complete readings include those by Jack Edwards (Helios/Hyperion, 1988-1991), and by David Butler (In Audio 2005) and Alex Jennings (Naxos 2006).

Audio versions of selected Sonnets by individual readers have been recorded by the actor Anthony Quayle 24 Sonnets, (1956) and by Dame Edith Evans, 20 Sonnets (EMI, early 1960s).

The best known "combined cast" audio versions of all the 154 Sonnets are those made by Dame Judi Dench, Ian McKellen, Michael Williams, Peter Egan, Peter Orr and Bob Peck (Penguin Classics 1995), and by Patrick Stewart, Natasha Richardson, Ossie Davis, Al Pacino, Claire Bloom, Kathleen Turner, Alfred Molina, Eli Wallach and others (AirplayAudio Publishing 2000).

Another complete version exists by a cast of various mainly North American readers, emphasized as being 'in the public domain'. (Librivox 2005/6).

An impressive cast of some 40 former alumni, young and old, of London's Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts perform on an audio rendition of 47 Sonnets, entitled 'When Love Speaks'. (EMI, released 4 February 2003).

An interpretation of Sonnet 130 by the British actor Alan Rickman is available in various versions (YouTube).

An interesting offering for linguists is a disc entitled 'Accents for Actors--Accents of Ireland, Wales, Scotland and England which provides "A Shakespeare Sonnet read in 20 different accents of the British Isles" (Clo-lar-Chonnachta, Eire: SAC 1027).

Complete audio-visual interpretations are also scarce and include a version with musical preludes by Jonathan Willby (2006)

Filmed readings of selected Sonnets include a video film entitled: "Shakespeare on Screen: selected Sonnets by Shakespeare" and described as "an educational program that gives an in-depth analysis of fifteen of Shakespeare's Sonnets". The cast of readers comprises the actors Ben Kingsley, Roger Rees, Claire Bloom and Jane Lapotaire with critical commentaries by A. L. Rowse, Leslie Fiedler, Stephen Spender, Gore Vidal, Arnold Wesker, Nicholas Humphrey and Roy Strong. (Kenneth S Rothwell and Annabelle Henkin Melzer, 1984).

A video version of 29 of the Sonnets was made, with a commentary, in various pastoral settings: at the breakfast table, over the telephone and as a standup comedy routine (Princeton, N.J-Films for the Humanities and Sciences, 2000)

In the arthouse drama film 'The Angelic Conversion', directed by Derek Jarman, Dame Judi Dench recites a number of the Sonnets (1985).

A complete audio-visual interpretation of the Sonnets is currently being produced and uploaded to Vimeo and YouTube by Flourish Klink, scheduled to be completed by the end of 2008.[17]

Musical settings of the sonnets are rare. Igor Stravinsky set Sonnet 8, "Music to hear", in his Three Songs From William Shakespeare. Benjamin Britten also set only one sonnet by Shakespeare, Sonnet 43, as the last part of his Nocturne. Maurice Johnston set Sonnet 75 "So are you to my thoughts". In 2007 the RSC ran Nothing Like the Sun, a project to set the sonnets to music.[18] Zehnder recorded Sonnet 30 on their CD Broken Train of Thought listed in the liner notes as '30'.

[edit] Modern editions

Legally, the sonnets (like all of Shakespeare's work) are in the public domain. This has prompted them to be reprinted in many editions.

- Martin Seymour-Smith (1963) Shakespeare's Sonnets (Oxford, Heinemann Educational)

- Stephen Booth (1977) Shakespeare's Sonnets (Yale)

- W G Ingram and Theodore Redpath (1978) Shakespeare's Sonnets, 2nd Edition

- John Kerrigan (1986) The Sonnets and a Lover's Complaint (Penguin)

- Katherine Duncan-Jones (1997) Shakespeare's Sonnets (Arden Edition, Third Series)

- Helen Vendler (1997) The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, Harvard University Press

- Colin Burrow (2002) The Complete Sonnets and Poems (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

- G. Blakemore Evans (1996) The Sonnets (Cambridge UP)

[edit] See also

[edit] Pop culture

Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 is referenced in the films Venus, Dead Poets Society, Shakespeare in Love, Clueless, and the 2007 Doctor Who episode "The Shakespeare Code" (in which Shakespeare addresses it to Martha Jones, calling her "my Dark Lady"). It also gave names to the band The Darling Buds and the books and television series The Darling Buds of May and Summer's Lease.

Ngaio Marsh's book Death at the Dolphin features a playwright, Peregrine Jay, who portrays a sexual relationship between the Dark Lady and Shakespeare in his latest work.

The Sonnet Lover, a novel by Carol Goodman, is constructed around the possibility that the Dark Lady was, in fact, a woman of Tuscany, and herself a creator of fine sonnets.

Daryl Mitchell's character, Mr. Morgan, quotes the first four lines of Sonnet 141 in the movie 10 Things I Hate About You.

Rufus Wainwright has put ten of Shakespeare's Sonnets to music (including 10, 20, 29, and 43) for a play from Robert Wilson and Berlin ensemble.

Shakespeare's Sonnet 73 has been turned into a song by the singer/songwriter Natalie Merchant.

There is a coarse version of the sonnets Variations on sonnets of Shakespeare

Kate Winslet's character, Marianne Dashwood, quotes from part of Shakespeare's Sonnet 116 in the 1995 film, Sense and Sensibility. [19]

[edit] Notes

- ^ Thorpe entered the book in the Stationers' Register on 20 May 1609: Evans, Gwynne Blakemore; Hecht, Anthony (eds.) (1996). The Sonnets. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 275. ISBN 0521222257.

- ^ Stanley Wells and Michael Dobson, eds., The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 439.

- ^ (2004). Sparknotes:No Fear Shakespeare: The Sonnets. New York, NY: Spark Publishing. ISBN 1-4114-0219-7.

- ^ Collins, John Churton. Ephemera Critica. Westminster, Constable and Co., 1902; p. 216.

- ^ Colin Burrow, ed. The Complete Sonnets and Poems (Oxford UP, 2002), p. 98-102-3.

- ^ Fields, Bertram. Players: The Mysterious Identity of William Shakespeare. New York: Harper Collins, 2005, 114

- ^ A metre in poetry with five iambic metrical feet, which stems from the Italian word endecasillabo, for a line composed of five beats with an anacrusis, an upbeat or unstressed syllable at the beginning of a line which is no part of the first foot.

- ^ Bray, Sir Denis. The Original Order of Shakespeare's Sonnets. (Brooklyn: Haskell House, 1977) p. 36

- ^ Muir, Kenneth. Shakespeare's Sonnets. (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1979) p. 57

- ^ McGuire, Philip C. Shakespeare's Non-Shakespearian Sonnets. Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 3 (Autumn, 1987) p. 304-319; 306

- ^ OxfordJournals.org

- ^ Stapleton, M. L. "Shakespeare's Man Right Fair as Sonnet Lady." Texas Studies in Literature and Language 46 (2004): 272

- ^ Sanderlin, George (June 1939). "The Repute of Shakespeare's Sonnets in the Early Nineteenth Century". Modern Language Notes 54 (6): 462–466. doi:.

- ^ Shakespeare's Sonnets in Latin, translated by Alfred Thomas Barton, newly edited by Ludwig Bernays, Edition Signathur, Dozwil/CH 2006

- ^ Shakespeare: La sonetoj (sonnets in Esperanto), Translated by William Auld, Edistudio, Edistudio Homepage, verified 2008/02/03

- ^ Selection of Shakespearean Sonnets, Translated by Nick Nicholas, verified 2005/02/27

- ^ The Sonnet Project

- ^ The Perfect Form

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0114388/trivia

[edit] External links

- The Sonnets – Compare two sonnets side-by-side, see all of them together on one page, or view a range of sonnets (from Open Source Shakespeare)

- The Sonnets – Full text and commentary.

- The Sonnets – Plain vanilla text from Project Gutenberg

- Shakepeare's Sonnets Overview of each in contemporary English

- Free audiobook from LibriVox

- Complete sonnets of William Shakespeare – Listed by number and first line.

- Gerald Massey - 'The Secret Drama of Shakspeare's Sonnets (1888 edition)

- Discussion of the identification of Emily Lanier as the Dark Lady

- Shakespeare Sonnet Shake-Up "Remix" Shakespeare's sonnets

- 'The Monument' by Hank Whittemore a new interpretation of Shakespeare's Sonnets

- shakespeareintune.com all the 154 Sonnets are here recited with a musical introduction.

[edit] Full list of sonnets

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||