Credit default swap

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A credit default swap (CDS) is a credit derivative contract between two counterparties. The buyer makes periodic payments to the seller, and in return receives a payoff if an underlying financial instrument defaults.[1]

CDS contracts have been compared with insurance, because the buyer pays a premium and, in return, receives a sum of money if one of the specified events occur. However, there are a number of differences between CDS and insurance, for example:

- the seller need not be a regulated entity;

- the seller is not required to maintain any reserves to pay off buyers, although all major CDS dealers are subject to bank capital requirements;

- insurers manage risk primarily by setting loss reserves based on the Law of Large Numbers, while dealers in CDS manage risk primarily by means of offsetting CDS (hedging) with other dealers and transactions in underlying bond markets;

- in the United States CDS contracts are generally subject to mark to market accounting, introducing income statement and balance sheet volatility that would not be present in an insurance contract;

- Hedge Accounting may not be available under US GAAP unless the requirements of FAS 133 are met; if it were not possible to, it could increase income statement and balance sheet volatility if the CDS was purchased to hedge an exposure;

- The buyer of a CDS does not need to own the underlying security or other form of credit exposure; in fact the buyer does not even have to suffer a loss from the default event.[2][3][4] By contrast, to purchase insurance the insured is generally expected to have an insurable interest such as owning a debt.

Contents |

[edit] Description

A credit default swap (CDS) is a swap contract in which the buyer of the CDS makes a series of payments to the seller and, in exchange, receives a payoff if a credit instrument - typically a bond or loan - goes into default (fails to pay). Less commonly, the credit event that triggers the payoff can be a company undergoing restructuring, bankruptcy or even just having its credit rating downgraded. Credit Default Swaps can be bought by any (relatively sophisticated) investor; it is not necessary for the buyer to own the underlying credit instrument.[5]

As an example, imagine that an investor buys a CDS from CITI Bank, where the reference entity is AIG Corp. The investor will make regular payments to CITI Bank, and if AIG Corp defaults on its debt (i.e., misses a coupon payment or does not repay it), the investor will receive a one-off payment from CITI Bank and the CDS contract is terminated. If the investor actually owns AIG Corp debt, the CDS can be thought of as hedging. But investors can also buy CDS contracts referencing AIG Corp debt, without actually owning any AIG Corp debt. This may be done for speculative purposes, to bet against the solvency of AIG Corp in a gamble to make money if it fails, or to hedge investments in other companies whose fortunes are expected to be similar to those of AIG.

If the reference entity (AIG Corp) defaults, one of two things can happen:

- Either the investor delivers a defaulted asset to CITI Bank for a payment of the par value. This is known as physical settlement.

- Or CITI Bank pays the investor the difference between the par value and the market price of a specified debt obligation (even if AIG Corp defaults, there is usually some recovery; i.e., not all your money will be lost.) This is known as cash settlement.[citation needed]

The spread of a CDS is the annual amount the protection buyer must pay the protection seller over the length of the contract, expressed as a percentage of the notional amount. For example, if the CDS spread of AIG Corp is 50 basis points, or 0.5% (1 basis point = 0.01%), then an investor buying $10 million worth of protection from CITI Bank must pay the bank $50,000 per year. These payments continue until either the CDS contract expires or AIG Corp defaults.

All things being equal, at any given time, if the maturity of two credit default swaps is the same, then the CDS associated with a company with a higher CDS spread is considered more likely to default by the market, since a higher fee is being charged to protect against this happening. However, factors such as liquidity and estimated loss given default can impact the comparison.

[edit] Uses

Like most financial derivatives, credit default swaps can be used by investors for speculation, hedging and arbitrage.

[edit] Speculation

Credit default swaps allow investors to speculate on changes in CDS spreads of single names or of market indexes such as the North American CDX index or the European iTraxx index. Or, an investor might believe that an entity's CDS spreads are either too high or too low relative to the entity's bond yields and attempt to profit from that view by entering into a trade, known as a basis trade, that combines a CDS with a cash bond and an interest rate swap. Finally, an investor might speculate on an entity's credit quality, since generally CDS spreads will increase as credit-worthiness declines, and decline as credit-worthiness increases. The investor might therefore buy CDS protection on a company in order to speculate that the company is about to default. Alternatively, the investor might sell protection if they think that the company's creditworthiness might improve.

For example, a hedge fund believes that AIG Corp will soon default on its debt. Therefore it buys $10 million worth of CDS protection for 2 years from CITI Bank, with AIG Corp as the reference entity, at a spread of 500 basis points (=5%) per annum.

- If AIG Corp does indeed default after, say, one year, then the hedge fund will have paid $500,000 to CITI Bank, but will then receive $10 million (assuming zero recovery rate, and that CITI Bank has the liquidity to cover the loss), thereby making a tidy profit. CITI Bank, and its investors, will incur a $9.5 million loss unless the bank has somehow offset the position before the default.

- However, if AIG Corp does not default, then the CDS contract will run for 2 years, and the hedge fund will have ended up paying $1 million, without any return, thereby making a loss.

Note that there is a third possibility in the above scenario; the hedge fund could decide to liquidate its position after a certain period of time in an attempt to lock in its gains or losses. For example:

- After 1 year, the market now considers AIG Corp more likely to default, so its CDS spread has widened from 500 to 1500 basis points. The hedge fund may choose to sell $10 million worth of protection for 1 year to CITI Bank at this higher rate. Therefore over the two years the hedge fund will pay the bank 2 * 5% * $10 million = $1 million, but will receive 1 * 15% * $10 million = $1.5 million, giving a total profit of $500,000 (so long as AIG Corp does not default during the second year).

- In another scenario, after one year the market now considers AIG much less likely to default, so its CDS spread has tightened from 500 to 250 basis points. Again, the hedge may choose to sell $10 million worth of protection for 1 year to CITI Bank at this lower spread. Therefore over the two years the hedge fund will pay the bank 2 * 5% * $10 million = $1 million, but will receive 1 * 2.5% * $10 million = $250,000, giving a total loss of $750,000 (so long as AIG Corp does not default during the second year). This loss is smaller than the $1 million loss that would have occurred if the second transaction had not been entered into.

Transactions such as these do not even have to be entered into over the long-term. If AIG Corp's CDS spread had widened by just a couple of basis points over the course of one day, the hedge fund could have entered into an offsetting contract immediately and made a small profit over the life of the two CDS contracts.

[edit] Hedging

Credit default swaps are often used to manage the credit risk (i.e. the risk of default) which arises from holding debt. Typically, the holder of, for example, a corporate bond may hedge their exposure by entering into a CDS contract as the buyer of protection. If the bond goes into default, the proceeds from the CDS contract will cancel out the losses on the underlying bond.

Pension fund example: A pension fund owns $10 million of a five-year bond issued by Risky Corp. In order to manage the risk of losing money if Risky Corp defaults on its debt, the pension fund buys a CDS from Derivative Bank in a notional amount of $10 million. The CDS trades at 200 basis points (200 basis points = 2.00 percent). In return for this credit protection, the pension fund pays 2% of 10 million ($200,000) per annum in quarterly installments of $50,000 to Derivative Bank.

- If Risky Corporation does not default on its bond payments, the pension fund makes quarterly payments to Derivative Bank for 5 years and receives its $10 million back after 5 years from Risky Corp. Though the protection payments totaling $1 million reduce investment returns for the pension fund, its risk of loss due to Risky Corp defaulting on the bond is eliminated.

- If Risky Corporation defaults on its debt 3 years into the CDS contract, the pension fund would stop paying the quarterly premium, and Derivative Bank would ensure that the pension fund is refunded for its loss of $10 million (either by physical or cash settlement - see above). The pension fund still loses the $600,000 it has paid over three years, but without the CDS contract it would have lost the entire $10 million.

| This subsection may require copy-editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone or spelling. You can assist by editing it now. A how-to guide is available. (February 2009) |

Hedging issues related to banks and corporations subject to taxation or using US GAAP for financial reporting: While the economics of entering into a CDS contract to hedge the credit risk in an asset is the same for a pension fund, a bank and a corporation, there are two significant practical differences in how hedges using CDS contracts affect banks and corporations compared to pension plans:

- Taxes - - for tax purposes the loss incurred on the Risky Corp.'s debt may be treated very differently from the payout by Derivative Bank to either a corporation or a bank. If the loss on the asset is taxed at a different rate from the profit made on the hedge, then the amount of the CDS swap needed to create a hedge of the Risky Corp.'s debt to the bank or corporation will differ from the [principle] amount of the debt. See Tax Treatment following.

- Financial reporting treatment may not parallel the economic effects. For example, GAAP generally require that Credit Default Swaps be reported on a mark to market basis, and assets that are held for investment, such as a commercial loan or bonds, be reported at cost unless a probable and significant loss is expected. Thus, hedging a commercial loan using a CDS can induce considerable volatility into the income statement and balance sheet as the CDS changes value over its life due to market conditions and due to the tendency for shorter dated CDS to sell at lower prices than longer dated CDS. Clearly, one can try to account for the CDS as a hedge under FASB 133 but in practice that can prove very difficult unless the risky asset owned by the bank or corporation is exactly the same as the Reference Obligation used for the particular CDS that was bought.

[edit] Risk

When entering into a CDS, both the buyer and seller of credit protection take on counterparty risk. Examples of counter party risks:

- The buyer takes the risk that the seller will default. If Derivative Bank and Risky Corp. default simultaneously ("double default"), the buyer loses its protection against default by the reference entity. If Derivative Bank defaults but Risky Corp. does not, the buyer might need to replace the defaulted CDS at a higher cost.

- The seller takes the risk that the buyer will default on the contract, depriving the seller of the expected revenue stream. More important, a seller normally limits its risk by buying offsetting protection from another party - that is, it hedges its exposure. If the original buyer drops out, the seller squares its position by either unwinding the hedge transaction or by selling a new CDS to a third party. Depending on market conditions, that may be at a lower price than the original CDS and may therefore involve a loss to the seller.

As is true with other forms of over-the-counter derivative, CDS might involve liquidity risk. If one or both parties to a CDS contract must post collateral(which is common), there can be margin calls requiring the posting of additional collateral. The required collateral is agreed on by the parties when the CDS is first issued. This margin amount may vary over the life of the CDS contract, if the market price of the CDS contract changes, or the credit rating of one of the parties changes.

[edit] Arbitrage

Capital Structure Arbitrage is an example of an arbitrage strategy which utilises CDS transactions.[6] This technique relies on the fact that a company's stock price and its CDS spread should exhibit negative correlation; i.e. if the outlook for a company improves then its share price should go up and its CDS spread should tighten, since it is less likely to default on its debt. However if its outlook worsens then its CDS spread should widen and its stock price should fall. Techniques reliant on this are known as capital structure arbitrage because they exploit market inefficiencies between different parts of the same company's capital structure; i.e. mis-pricings between a company's debt and equity. An arbitrageur will attempt to exploit the spread between a company's CDS and its equity in certain situations. For example, if a company has announced some bad news and its share price has dropped by 25%, but its CDS spread has remained unchanged, then an investor might expect the CDS spread to increase relative to the share price. Therefore a basic strategy would be to go long on the CDS spread (by buying CDS protection) while simultaneously hedging oneself by buying the underlying stock. This technique would benefit in the event of the CDS spread widening relative to the equity price, but would lose money if the company's CDS spread tightened relative to its equity.

An interesting situation in which the inverse correlation between a company's stock price and CDS spread breaks down is during a leveraged buyout (LBO). Frequently this will lead to the company's CDS spread widening due to the extra debt that will soon be put on the company's books, but also an increase in its share price, since buyers of a company usually end up paying a premium.

Another common arbitrage strategy aims to exploit the fact that the swap adjusted spread of a CDS should trade closely with that of the underlying cash bond issued by the reference entity. Misalignments in spreads may occur due to technical reasons such as specific settlement differences, shortages in a particular underlying instrument, and the existence of buyers constrained from buying exotic derivatives. The difference between CDS spreads and asset swap spreads is called the basis and should theoretically be close to zero. Basis trades can aim to exploit any differences to make risk-free profits.

[edit] History

[edit] Conception

Credit Default Swaps were invented in 1997 by a team working for JPMorgan Chase[7][8][9]. They were designed to shift the risk of default to a third party, and were therefore less punitive in terms of regulatory capital.[10]

Credit Default Swaps became largely exempt from regulation by the SEC and the CFTC with the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, which was also responsible for the Enron loophole. President Clinton signed the bill into Public Law (106-554) on December 21, 2000.

[edit] Market growth

By the end of 2007, the CDS market had a notional value of $45 trillion. As the market matured, CDSs were increasingly used by investors wishing to bet for or against the likelihood that particular companies or portfolios would suffer financial difficulties; rather than to insure against bad debt -see above. The market size for Credit Default Swaps began to grow rapidly from 2003, by late 2007 it was approximately ten times as large as it had been four years previously. [11]

[edit] Market as of 2008

Credit default swaps are by far the most widely traded credit derivative product.[12] the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation, which maintains a database holding around 90% of all credit derivative transactions, held $29.2 trillion of outstanding CDS trades as of 26 December 2008.

It is important to note that since default is a relatively rare occurrence (historically around 0.2% of investment grade companies will default in any one year[13]), in most CDS contracts the only payments are the spread payments from buyer to seller. Thus, although the above figures for outstanding notionals sound very large, the net cashflows will generally only be a small[specify] fraction of this total.

[edit] Regulatory concerns over CDS

A number of large scale incidents occurring in 2008 drew considerable attention onto the CDS.[citation needed]

In the days and weeks leading up to the collapse of Bear Stearns, the bank's CDS spread widened dramatically, indicating a surge of buyers taking out protection on the bank. It has been suggested that this widening was responsible for the perception that Bear Stearns was vulnerable, and therefore restricted its access to wholesale capital which eventually led to its forced sale to JP Morgan in March. An alternative view is that this surge in CDS protection buyers was a symptom rather than a cause of Bear's collapse; i.e. investors saw that Bear was in trouble, and sought to hedge any naked exposure to the bank, or speculate on its collapse.

In September the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers caused a total close to $400 Billion to become payable to the buyers of CDS protection referenced against the insolvent bank. However the net amount that changed hands was around $7.2 billion [14] This difference is due to the process of 'netting'. Market participants co-operated so that CDS sellers were allowed to deduct from their payouts the inbound funds due to them from their hedging positions. Dealers generally attempt to remain risk-neutral so their losses and gains after big events will on the whole offset each other.

Also in September American International Group (AIG) required a federal bailout because it had been excessively selling CDS protection without hedging against the possibility that the reference entities might decline in value, which exposed the insurance giant to potential losses over $100 Billion. The CDS on Lehman were settled smoothly, as was largely the case for the other 11 credit events occuring in 2008 which triggered payouts[15]. And while its arguable that other incidents would have been as bad or worse if less efficient instruments than CDS had been used for speculation and insurance purposes, the closing months of 2008 saw regulators working hard to reduce the risk involved in CDS transactions.

In 2008 there was no centralized exchange or clearing house for CDS transactions; they were all done over the counter (OTC). This led to recent calls for the market to open up in terms of transparency and regulation[16]. In November, DTCC, which runs a warehouse for CDS trade confirmations accounting for around 90% of the total market[17], announced that it will release market data on the outstanding notional of CDS trades on a weekly basis.[18] The data can be accessed on the DTCC's website here: [7] The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission granted an exemption for IntercontinentalExchange to begin guaranteeing credit-default swaps.

The SEC exemption represented the last regulatory approval needed by Atlanta-based Intercontinental. Its larger competitor, CME Group Inc., hasn’t received an SEC exemption, and agency spokesman John Nester said he didn’t know when a decision would be made.

[edit] Market as of 2009

The early months of 2009 saw several fundamental changes to the way CDSs operate, resulting from concerns over the instrument's safety after the events of the previous year. According to Deutsche Bank managing director Athanassos Diplas "the industry pushed through 10 years worth of changes in just a few months" By late 2008 processes had been introduced allowing CDSs which offset each other to be cancelled. Along with termination of contracts that have recently paid out such as those based on Lehmans, this had by March reduced the face value of the market down to an estimated $30 trillion. [19] U.S. and European regulators are developing separate plans to stabilize the derivatives market. Additionally there are some globally agreed standards falling into place in March 2009, administered by International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). Two of the key changes are:

1. The introduction of central clearing houses, one for the US and one for Europe. A clearing house acts as the central counterparty to both sides of a CDS transaction, thereby reducing the counterparty risk that both buyer and seller face.

2. The international standardization of CDS contracts, to prevent legal disputes in ambiguous cases where its not clear what the payout should be.

Speaking before the changes went live , Sivan Mahadevan, a derivatives strategist at Morgan Stanley in New York, stated

| “ | A clearinghouse, and changes to the contracts to standardize them, will probably boost activity. ... Trading will be much easier, ... We'll see new players come to the market because they’ll like the idea of this being a better and more traded product. We also feel like over time we'll see the creation of different types of products. | ” |

In the US central clearing operations began in March 2009 , operated by InterContinental Exchange (ICE). A key competitor also interested in entering the CDS clearing sector is CME Group.

Details for a European clearing are still being hammered out.

[edit] Government Approvals Relating to Intercontinental and its competitor CME

The SECs approval for ICE's request to be exempted from rules that would prevent it clearing CDSs is the third government action granted to Intercontinental this week. On March 3, its proposed acquisition of Clearing Corp., a Chicago clearinghouse owned by eight of the largest dealers in the credit-default swap market, was approved by the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department. On March 5, the Federal Reserve Board, which oversees the clearinghouse, granted a request for ICE to begin clearing.

Clearing Corp. shareholders including JPMorgan Chase & Co., Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and UBS AG, received $39 million in cash from Intercontinental in the acquisition, as well as the Clearing Corp.’s cash on hand and a 50-50 profit-sharing agreement with Intercontinental on the revenue generated from processing the swaps.

SEC spokesperson John Nestor stated

| “ | For several months the SEC and our fellow regulators have worked closely with all of the firms wishing to establish central counterparties. ... We believe that CME should be in a position soon to provide us with the information necessary to allow the commission to take action on its exemptive requests. | ” |

Other proposals to clear credit-default swaps have been made by NYSE Euronext, Eurex AG and LCH.Clearnet Ltd. Only the NYSE effort is available now for clearing after starting on Dec. 22. As of Jan. 30, no swaps had been cleared by the NYSE’s London- based derivatives exchange, according to NYSE Chief Executive Officer Duncan Niederauer. [20]

[edit] Clearing House Member Requirements

Members of the Intercontinental clearinghouse will have to have a net worth of at least $5 billion and a credit rating of A or better to clear their credit-default swap trades. Intercontinental said in the statement today that all market participants such as hedge funds, banks or other institutions are open to become members of the clearinghouse as long as they meet these requirements.

A clearinghouse acts as the buyer to every seller and seller to every buyer, reducing the risk of a counterparty defaulting on a transaction. In the over-the-counter market, where credit- default swaps are currently traded, participants are exposed to each other in case of a default. A clearinghouse also provides one location for regulators to view traders’ positions and prices.

[edit] Other changes and debate on CDS in 2009

There is ongoing debate concerning the possibility of limiting so-called "naked" CDSs. A naked CDS is one where the buyer has no risk exposure to the underlying entity; hence naked CDSs do not hedge risk per se, but are mere speculative bets that actually create risk. Some suggest that buyers be required to have a "stake," or element of risk exposure, in the underlying entity that the CDS pays out on. [21] Others suggest that a mere partial stake in the underlying risk is insufficient, and would insist that buyer protection be limited to insurable risk; that is, the actual value of the capital-at-risk in the underlying entity. This means the CDS buyer would have to own the bond or loan that triggers a pay out on default. Still others, also calling for the outright ban of naked CDSs, cite logic similar to that which prevailed in the call to ban markets for "terroristic events;" - namely, that it is poor public policy to provide financial incentive to one party which pay offs only when some other party suffers a loss - the argument being that it is foolish to incentivize the first party to nefariously intervene in the affairs of the second party so as to cause, or to contribute to cause, the second party loss event which has been speculated upon by the first party; such action, should it occur, is called "fomenting the loss". Regardless of the intention of the buyers and sellers of "naked" contracts, it is the absence of ownership risk that is determinate.

[edit] Terms of a typical CDS contract

A CDS contract is typically documented under a confirmation referencing the credit derivatives definitions as published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association.[22] The confirmation typically specifies a reference entity, a corporation or sovereign that generally, although not always, has debt outstanding, and a reference obligation, usually an unsubordinated corporate bond or government bond. The period over which default protection extends is defined by the contract effective date and scheduled termination date.

The confirmation also specifies a calculation agent who is responsible for making determinations as to successors and substitute reference obligations (for example necessary if the original reference obligation was a loan that is repaid before the expiry of the contract), and for performing various calculation and administrative functions in connection with the transaction. By market convention, in contracts between CDS dealers and end-users, the dealer is generally the calculation agent, and in contracts between CDS dealers, the protection seller is generally the calculation agent. It is not the responsibility of the calculation agent to determine whether or not a credit event has occurred but rather a matter of fact that, pursuant to the terms of typical contracts, must be supported by publicly available information delivered along with a credit event notice. Typical CDS contracts do not provide an internal mechanism for challenging the occurrence or non-occurrence of a credit event and rather leave the matter to the courts if necessary, though actual instances of specific events being disputed are relatively rare.

CDS confirmations also specify the credit events that will give rise to payment obligations by the protection seller and delivery obligations by the protection buyer. Typical credit events include bankruptcy with respect to the reference entity and failure to pay with respect to its direct or guaranteed bond or loan debt. CDS written on North American investment grade corporate reference entities, European corporate reference entities and sovereigns generally also include restructuring as a credit event, whereas trades referencing North American high yield corporate reference entities typically do not. The definition of restructuring is quite technical but is essentially intended to respond to circumstances where a reference entity, as a result of the deterioration of its credit, negotiates changes in the terms in its debt with its creditors as an alternative to formal insolvency proceedings (i.e., the debt is restructured). This practice is far more typical in jurisdictions that do not provide protective status to insolvent debtors similar to that provided by Chapter 11 of the United States Bankruptcy Code. In particular, concerns arising out of Conseco's restructuring in 2000 led to the credit event's removal from North American high yield trades.[23]

Finally, standard CDS contracts specify deliverable obligation characteristics that limit the range of obligations that a protection buyer may deliver upon a credit event. Trading conventions for deliverable obligation characteristics vary for different markets and CDS contract types. Typical limitations include that deliverable debt be a bond or loan, that it have a maximum maturity of 30 years, that it not be subordinated, that it not be subject to transfer restrictions (other than Rule 144A), that it be of a standard currency and that it not be subject to some contingency before becoming due.

[edit] Settlement

As described in an earlier section, if a credit event occurs then CDS contracts can either be physically settled or cash settled.

- Physical settlement: The protection seller pays the buyer par value, and in return takes delivery of a debt obligation of the reference entity. For example, a hedge fund has bought $5 million worth of protection from a bank on the senior debt of a company. In the event of a default, the bank will pay the hedge fund $5 million cash, and the hedge fund must deliver $5 million face value of senior debt of the company (typically bonds or loans, which will typically be worth very little given that the company is in default).

- Cash settlement: The protection seller pays the buyer the difference between par value and the market price of a debt obligation of the reference entity. For example, a hedge fund has bought $5 million worth of protection from a bank on the senior debt of a company. This company has now defaulted, and its senior bonds are now trading at 25 (i.e. 25 cents on the dollar) since the market believes that senior bondholders will receive 25% of the money they are owed once the company is wound up. Therefore, the bank must pay the hedge fund $5 million * (100%-25%) = $3.75 million.

The development and growth of the CDS market has meant that on many companies there is now a much larger outstanding notional of CDS contracts than the outstanding notional value of its debt obligations. (This is because many parties made CDS contracts for speculative purposes, without actually owning any debt for which they wanted to insure against default.) For example, at the time it filed for bankruptcy on 14 September 2008, Lehman Brothers had approximately $155 billion of outstanding debt[24] but around $400 billion notional value of CDS contracts had been written which referenced this debt.[25] Clearly not all of these contracts could be physically settled, since there was not enough outstanding Lehman Brothers debt to fulfill all of the contracts, demonstrating the necessity for cash settled CDS trades. The trade confirmation produced when a CDS is traded will state whether the contract is to be physically or cash settled.

[edit] Auctions

When a credit event occurs on a major company on which a lot of CDS contracts are written, an auction (also known as a credit-fixing event) may be held to facilitate settlement of a large number of contracts at once, at a fixed cash settlement price. During the auction process participating dealers (eg the big investment banks) submit prices at which they would buy and sell the reference entity's debt obligations, as well as net requests for physical settlement against par. A second stage Dutch auction is held following the publication of the initial mid-point of the dealer markets and what is the net open interest to deliver or be delivered actual bonds or loans. The final clearing point of this auction sets the final price for cash settlement of all CDS contracts and all physical settlement requests as well as matched limit offers resulting from the auction are actually settled. According to the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA), who organised them, auctions have recently proved an effective way of settling the very large volume of outstanding CDS contracts written on companies such as Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual.[26]

Below is a list of the auctions that have been held since 2005.[27]

| Date | Name | Final price as a percentage of par |

|---|---|---|

| 2005-06-14 | Collins & Aikman - Senior | 43.625 |

| 2005-06-23 | Collins & Aikman - Subordinated | 6.375 |

| 2005-10-11 | Northwest Airlines | 28 |

| 2005-10-11 | Delta Airlines | 18 |

| 2005-11-04 | Delphi Corporation | 63.375 |

| 2006-01-17 | Calpine Corporation | 19.125 |

| 2006-03-31 | Dana Corporation | 75 |

| 2006-11-28 | Dura - Senior | 24.125 |

| 2006-11-28 | Dura - Subordinated | 3.5 |

| 2007-10-23 | Movie Gallery | 91.5 |

| 2008-02-19 | Quebecor | 41.25 |

| 2008-10-02 | Tembec Inc | 83 |

| 2008-10-06 | Fannie Mae - Senior | 91.51 |

| 2008-10-06 | Fannie Mae - Subordinated | 99.9 |

| 2008-10-06 | Freddie Mac - Senior | 94 |

| 2008-10-06 | Freddie Mac - Subordinated | 98 |

| 2008-10-10 | Lehman Brothers | 8.625 |

| 2008-10-23 | Washington Mutual | 57 |

| 2008-11-04 | Landsbanki - Senior | 1.25 |

| 2008-11-04 | Landsbanki - Subordinated | 0.125 |

| 2008-11-05 | Glitnir - Senior | 3 |

| 2008-11-05 | Glitnir - Subordinated | 0.125 |

| 2008-11-06 | Kaupthing - Senior | 6.625 |

| 2008-11-06 | Kaupthing - Subordinated | 2.375 |

| 2008-12-09 | Masonite [8] - LCDS | 52.5 |

| 2008-12-17 | Hawaiian Telcom - LCDS | 40.125 |

| 2009-01-06 | Tribune - CDS | 1.5 |

| 2009-01-06 | Tribune - LCDS | 23.75 |

| 2009-01-14 | Republic of Ecuador | 31.375 |

| 2009-02-03 | Millennium America Inc | 7.125 |

| 2009-02-03 | Lyondell - CDS | 15.5 |

| 2009-02-03 | Lyondell - LCDS | 20.75 |

| 2009-02-03 | EquiStar | 27.5 |

| 2009-02-05 | Sanitec [9] - 1st Lien | 33.5 |

| 2009-02-05 | Sanitec [10] - 2nd Lien | 4.0 |

| 2009-02-09 | British Vita [11] | TBA |

[edit] Pricing and valuation

There are two competing theories usually advanced for the pricing of credit default swaps. The first, which for convenience we will refer to as the 'probability model', takes the present value of a series of cashflows weighted by their probability of non-default. This method suggests that credit default swaps should trade at a considerably lower spread than corporate bonds.

The second model, proposed by Darrell Duffie, but also by Hull and White, uses a no-arbitrage approach.

[edit] Probability model

Under the probability model, a credit default swap is priced using a model that takes four inputs:

- the issue premium,

- the recovery rate (percentage of notional repaid in event of default),

- the credit curve for the reference entity and

- the LIBOR curve.

If default events never occurred the price of a CDS would simply be the sum of the discounted premium payments. So CDS pricing models have to take into account the possibility of a default occurring some time between the effective date and maturity date of the CDS contract. For the purpose of explanation we can imagine the case of a one year CDS with effective date t0 with four quarterly premium payments occurring at times t1, t2, t3, and t4. If the nominal for the CDS is N and the issue premium is c then the size of the quarterly premium payments is Nc / 4. If we assume for simplicity that defaults can only occur on one of the payment dates then there are five ways the contract could end: either it does not have any default at all, so the four premium payments are made and the contract survives until the maturity date, or a default occurs on the first, second, third or fourth payment date. To price the CDS we now need to assign probabilities to the five possible outcomes, then calculate the present value of the payoff for each outcome. The present value of the CDS is then simply the present value of the five payoffs multiplied by their probability of occurring.

This is illustrated in the following tree diagram where at each payment date either the contract has a default event, in which case it ends with a payment of N(1 − R) shown in red, where R is the recovery rate, or it survives without a default being triggered, in which case a premium payment of Nc / 4 is made, shown in blue. At either side of the diagram are the cashflows up to that point in time with premium payments in blue and default payments in red. If the contract is terminated the square is shown with solid shading.

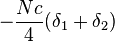

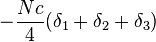

The probability of surviving over the interval ti − 1 to ti without a default payment is pi and the probability of a default being triggered is 1 − pi. The calculation of present value, given discount factors of δ1 to δ4 is then

| Description | Premium Payment PV | Default Payment PV | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default at time t1 |  |

|

|

| Default at time t2 |  |

|

|

| Default at time t3 |  |

|

|

| Default at time t4 |  |

|

|

| No defaults |  |

|

|

The probabilities p1, p2, p3, p4 can be calculated using the credit spread curve. The probability of no default occurring over a time period from t to t + Δt decays exponentially with a time-constant determined by the credit spread, or mathematically p = exp( − s(t)Δt) where s(t) is the credit spread zero curve at time t. The riskier the reference entity the greater the spread and the more rapidly the survival probability decays with time.

To get the total present value of the credit default swap we multiply the probability of each outcome by its present value to give

|

|

|

![+ p_1 ( 1 - p_2 ) [ N(1-R) \delta_2 - \frac{Nc}{4} \delta_1 ]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/0/4/504c92c6bbc8abd731bf404c05c28e40.png) |

||

![+p_1 p_2 ( 1 - p_3 ) [ N(1-R) \delta_3 - \frac{Nc}{4} (\delta_1 + \delta_2) ]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/2/1/b2189b1eab2356219441644c3e8e6026.png) |

||

![+p_1 p_2 p_3 (1 - p_4) [ N(1-R) \delta_4 - \frac{Nc}{4} (\delta_1 + \delta_2 + \delta_3) ]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/e/d/d/edd972c8c98ac6ce4665b63d107e2e43.png) |

||

|

[edit] No-arbitrage model

In the 'no-arbitrage' model proposed by both Duffie, and Hull-White, it is assumed that there is no risk free arbitrage. Duffie uses the LIBOR as the risk free rate, whereas Hull and White use US Treasuries as the risk free rate. Both analyses make simplifying assumptions (such as the assumption that there is zero cost of unwinding the fixed leg of the swap on default), which may invalidate the no-arbitrage assumption. However the Duffie approach is frequently used by the market to determine theoretical prices. Under the Duffie construct, the price of a credit default swap can also be derived by calculating the asset swap spread of a bond. If a bond has a spread of 100, and the swap spread is 70 basis points, then a CDS contract should trade at 30. However there are sometimes technical reasons why this will not be the case, and this may or may not present an arbitrage opportunity for the canny investor. The difference between the theoretical model and the actual price of a credit default swap is known as the basis.

[edit] Criticisms

Critics of the huge credit default swap market have claimed that it has been allowed to become too large without proper regulation and that, because all contracts are privately negotiated, the market has no transparency. Furthermore, there have even been claims that CDSs exacerbated the 2008 global financial crisis by hastening the demise of companies such as Lehman Brothers and AIG.[28]

In the case of Lehman Brothers, it is claimed that the widening of the bank's CDS spread reduced confidence in the bank and ultimately gave it further problems that it was not able to overcome. However, proponents of the CDS market argue that this confuses cause and effect; CDS spreads simply reflected the reality that the company was in serious trouble. Furthermore, they claim that the CDS market allowed investors who had counterparty risk with Lehman Brothers to reduce their exposure in the case of their default.

It was also reported after Lehman's bankruptcy that the $400 billion notional of CDS protection which had been written on the bank could lead to a net payout of $366 billion from protection sellers to buyers (given the cash-settlement auction settled at a final price of 8.625%) and that these large payouts could lead to further bankruptcies of firms without enough cash to settle their contracts.[29] However, industry estimates after the auction suggested that net cashflows would only be in the region of $7 billion.[29] This is because many parties held offsetting positions; for example if a bank writes CDS protection on a company it is likely to then enter an offsetting transaction by buying protection on the same company in order to hedge its risk. Furthermore, CDS deals are marked-to-market frequently. This would have led to margin calls from buyers to sellers as Lehman's CDS spread widened, meaning that the net cashflows on the days after the auction are likely to have been even lower.[26] Senior bankers have argued that not only has the CDS market functioned remarkably well during the financial crisis, but that CDS contracts have been acting to distribute risk just as was intended, and that it is not CDSs themselves that need further regulation, but the parties who trade them. [30]

Some general criticism of financial derivatives is also relevant to credit derivatives. Warren Buffett famously described derivatives bought speculatively as "financial weapons of mass destruction." In Berkshire Hathaway's annual report to shareholders in 2002, he said, "Unless derivatives contracts are collateralized or guaranteed, their ultimate value also depends on the creditworthiness of the counterparties to them. In the meantime, though, before a contract is settled, the counterparties record profits and losses—often huge in amount—in their current earnings statements without so much as a penny changing hands. The range of derivatives contracts is limited only by the imagination of man (or sometimes, so it seems, madmen)."[31] It is true that entering a CDS transaction gives you counterparty risk, but bear in mind that it is also possible to hedge this risk by buying CDS protection on your counterparty! Furthermore, it is not strictly true to say that profit and loss is recorded without any money changing hands since positions are marked-to-market daily and collateral will pass from buyer to seller (or vice versa) to protect both parties against counterparty default. It is also worth noting that Buffett seems to have since changed his stance on derivatives since he made this statement, since in October 2008 Berkshire Hathaway was forced to reveal to regulators that it has entered into at least $4.85 billion in derivative transactions.[32] In addition, Berkshire Hathaway was a large owner of Moody's stock during the period that it was one of two primary rating agencies for subprime CDOs, a form of mortgage security derivative dependant on the use of credit default swaps.

[edit] Systemic risk

The risk of counterparties defaulting has been amplified during the 2008 financial crisis, particularly because Lehman Brothers and AIG were counterparties in a very large number of CDS transactions. This is an example of systemic risk, risk which threatens an entire market, and a number of commentators have argued that size and deregulation of the CDS market have increased this risk.

For example, imagine if a hypothetical mutual fund had bought some Washington Mutual corporate bonds in 2005 and decided to hedge their exposure by buying CDS protection from Lehman Brothers. After Lehman's default, this protection was no longer active, and Washington Mutual's sudden default only days later would have led to a massive loss on the bonds, a loss that should have been insured by the CDS. There was also fear that Lehman Brothers and AIG's inability to pay out on CDS contracts would lead to the unraveling of complex interlinked chain of CDS transactions between financial institutions.[33] So far this does not appear to have happened, although some commentators have noted that because the total CDS exposure of a bank is not public knowledge, the fear that one could face large losses or possibly even default themselves was a contributing factor to the massive decrease in lending liquidity during September/October 2008.[34]

Chains of CDS transactions can arise from a practice known as "netting".[35] Here, company B may buy a CDS from company A with a certain annual "premium", say 2%. If the condition of the reference company worsens, the risk premium will rise, so company B can sell a CDS to company C with a premium of say, 5%, and pocket the 3% difference. However, if the reference company defaults, company B might not have the assets on hand to make good on the contract. It depends on its contract with company A to provide a large payout, which it then passes along to company C. The problem lies if one of the companies in the chain fails, creating a "domino effect" of losses. For example, if company A fails, company B will default on its CDS contract to company C, possibly resulting in bankruptcy, and company C will potentially experience a large loss due to the failure to receive compensation for the bad debt it held from the reference company. Even worse, because CDS contracts are private, company C will not know that its fate is tied to company A; it is only doing business with company B.

As described above, the establishment of a central exchange or clearing house for CDS trades would help to solve the "domino effect" problem, since it would mean that all trades faced a central counterparty guaranteed by a consortium of dealers.

[edit] Tax treatment

The U.S federal income tax treatment of credit default swaps is uncertain.[36] Commentators generally believe that, depending on how they are drafted, they are either notional principal contracts or options for tax purposes,[37] but this is not certain. There is a risk of having credit default swaps recharacterized as different types of financial instruments because they resemble put options and credit guarantees. In particular, the degree of risk depends on the type of settlement (physical/cash and binary/FMV) and trigger (default only/any credit event).[38] If a credit default swap is a notional principal contract, periodic and nonperiodic payments on the swap are deductible and included in ordinary income.[39] If a payment is a termination payment, its tax treatment is even more uncertain.[40] In 2004, the Internal Revenue Service announced that it was studying the characterization of credit default swaps in response to taxpayer confusion,[41] but it has not yet issued any guidance on their characterization. A taxpayer must include income from credit default swaps in ordinary income if the swaps are connected with trade or business in the United States.[42]

[edit] LCDS

A new type of default swap is the "loan only" credit default swap (LCDS). This is conceptually very similar to a standard CDS, but unlike "vanilla" CDS, the underlying protection is sold on syndicated secured loans of the Reference Entity rather than the broader category of "Bond or Loan". Also, as of May 22, 2007, for the most widely traded LCDS form, which governs North American single name and index trades, the default settlement method for LCDS shifted to auction settlement rather than physical settlement. The auction method is essentially the same that has been used in the various ISDA cash settlement auction protocols, but does not require parties to take any additional steps following a credit event (i.e., adherence to a protocol) to elect cash settlement. On October 23, 2007, the first ever LCDS auction was held for Movie Gallery.[12]

Because LCDS trades are linked to secured obligations with much higher recovery values than the unsecured bond obligations that are typically assumed to be cheapest to deliver in respect of vanilla CDS, LCDS spreads are generally much tighter than CDS trades on the same name.

[edit] See also

| Look up credit default swap in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Credit default option

- Credit default swap index

- Constant maturity credit default swap

- Credit derivative

- Monoline

- Recovery swap

- Swap (finance)

- Bucket shop (stock market)

[edit] References

- ^ CFA Institute. (2008). Derivatives and Alternative Investments. pg G-11. Boston: Pearson Custom Publishing. ISBN 0-536-34228-8.

- ^ Mark Garbowski (2008-10-24). "United States: Credit Default Swaps: A Brief Insurance Primer". http://www.mondaq.com/article.asp?articleid=68548. Retrieved on 2008-11-03. "like insurance insofar as the buyer collects when an underlying security defaults ... unlike insurance, however, in that the buyer need not have an "insurable interest" in the underlying security"

- ^ Gretchen Morgenson (2008-08-10). "Credit default swap market under scrutiny". http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/08/10/business/morgen11.php. Retrieved on 2008-11-03. "If a default occurs, the party providing the credit protection - the seller - must make the buyer whole on the amount of insurance bought."

- ^ Karel Frielink (2008-08-10). "Are credit default swaps insurance products?". http://www.curacao-law.com/2008/06/17/credit-default-swaps-and-insurance-issues-under-dutch-caribbean-law/. Retrieved on 2008-11-03. "If the fund manager acts as the protection seller under a CDS, there is some risk of breach of insurance regulations for the manager. ... There is no Netherlands Antilles case law or literature available which makes clear whether a CDS constitutes the ‘conducting of insurance business’ under Netherlands Antilles law. However, if certain requirements are met, credit derivatives will not qualify as an agreement of (non-life) insurance because such an arrangement would in those circumstances not contain all the elements necessary to qualify it as such."

- ^ [1]Cox, Christopher, Chairman, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Testimony Concerning Turmoil in U.S. Credit Markets: Recent Actions Regarding Government Sponsored Entities, Investment Banks and Other Financial Institutions. Before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs. September 23, 2008. Accessed 3-17-09.

- ^ [2]Chatiras, Manolis, and Barsendu Mukherjee. Capital Structure Arbitrage: Investigation using Stocks and High Yield Bonds. Amherst, MA: Center for International Securities and Derivatives Markets, Isenberg School of Management, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 2004. Accessed 3-17-09.

- ^ [3]Teather, David. “The woman who Built financial ‘Weapon of Mass Destruction.’” The Guardian. September 20, 2008. Accessed 3-17-09

- ^ Engdahl, William (2008-06-06). "CREDIT DEFAULT SWAPS THE NEXT CRISIS". http://www.financialsense.com/editorials/engdahl/2008/0606.html. Retrieved on 2008-11-02.

- ^ [4] Tett, Gillian. “The Dream Machine: Invention of Credit Derivatives. Financial Times. March 24, 2006. Accessed 3-17-09.

- ^ "Credit Default Swaps: From Protection To Speculation". http://www.rkmc.com/Credit-Default-Swaps-From-Protection-To-Speculation.htm. Retrieved on 02 January 2009.

- ^ Lewis, Nathan (2007-12-07). "Meanwhile in the Derivatives Market". http://goldnews.bullionvault.com/derivatives_mortgage_bonds_credit_default_121320074. Retrieved on 2008-11-02.

- ^ "British Bankers Association Credit Derivatives Report" (PDF). http://www.bba.org.uk/content/1/c4/76/71/Credit_derivative_report_2006_exec_summary.pdf.

- ^ http://www.efalken.com/banking/html's/defaultcurves.htm

- ^ http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/25137702-972d-11dd-8cc4-000077b07658.html

- ^ Colin Barr. "The truth about credit default swaps". CNN / Fortune. http://money.cnn.com/2009/03/16/markets/cds.bear.fortune/index.htm. Retrieved on 2009-03-27.

- ^ http://www.sec.gov/news/testimony/2008/ts092308cc.htm

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2008/nov/05/creditcrunch-marketturmoil

- ^ http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601085&sid=aZYSaaTg9xJg&refer=europe

- ^ Aline Van Duyn. "Worries Remain Even After CDS Clean-Up". The Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/af1efb78-0dc6-11de-8ea3-0000779fd2ac.html. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ Matthew Leising and Shannon D. Harrington. "Intercontinental to Clear Credit Swaps Next Week". Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=afJz1FLOy1nI&refer=home. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ Aline Van Duyn. "Worries Remain Even After CDS Clean-Up". The Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/af1efb78-0dc6-11de-8ea3-0000779fd2ac.html. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ 2003 Credit Derivatives Definitions

- ^ Financewise.com

- ^ http://seekingalpha.com/article/99286-settlement-auction-for-lehman-cds-surprises-ahead

- ^ http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/7a268486-93cd-11dd-9a63-0000779fd18c,dwp_uuid=11f94e6e-7e94-11dd-b1af-000077b07658.html

- ^ a b http://www.isda.org/press/press102108.html

- ^ Markit. Tradeable Credit Fixings. Retrieved 2008-10-28

- ^ [5]Phillips, Matthew. “The Monster That Ate Wall Street.” Newsweek. October 6, 2008. Accessed 3-17-09.

- ^ a b http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/d96751f8-96f4-11dd-8cc4-000077b07658.html

- ^ "Daily Brief". 2008-10-28. http://www.spectator.co.uk/business/trading-floor/2556276/daily-brief.thtml. Retrieved on 2008-11-06.

- ^ Warren Buffett (2003-02-21). "Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Annual Report 2002" (PDF). Berkshire Hathaway. http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/2002ar/2002ar.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-09-21.

- ^ http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aQwp2qwvFuE8

- ^ http://kciinvesting.com/articles/9432/1/AIG-the-Global-Financial-System-and-Investor-Anxiety/Page1.html

- ^ http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/investing-and-markets/article.html?in_article_id=455675&in_page_id=3

- ^ Unregulated Credit Default Swaps Led to Weakness. All things Considered, National Public Radio. 31 Oct 2008.

- ^ Nirenberg, David Z. & Steven L. Kopp. “Credit Derivatives: Tax Treatment of Total Return Swaps, Default Swaps, and Credit-Linked Notes,” Journal of Taxation, Aug. 1997: 1. Peaslee, James M. & David Z. Nirenberg. Federal Income Taxation of Securitization Transactions: Cumulative Supplement No. 7, November 26, 2007, http://www.securitizationtax.com: 85. Retrieved July 28, 2008. Ari J. Brandes. A Better Way to Understand Credit Default Swaps. Tax Notes (July 21, 2008). Earlier version of paper available at: [6].

- ^ Peaslee & Nirenberg, 129.

- ^ Nirenberg & Kopp, 8.

- ^ Id.

- ^ Id.

- ^ Peaslee & Nirenberg, 89.

- ^ Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, at the IRS website. “2007 Instructions for Form 1042-S: Foreign Person’s U.S. Source Income Subject to Withholding,” http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i1042s_07.pdf: 4. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

[edit] External links

- "Systemic Counterparty Confusion: Credit Default Swaps Demystified". Derivative Dribble. October 23, 2008.

- CBS '60 minutes' video on CDS

- 2003 ISDA Credit Derivatives Template. International Swaps and Derivatives Association

- BIS - Regular Publications. Bank for International Settlements.

- OCC - Quarterly Derivatives Fact Sheet

- A Beginner's Guide to Credit Derivatives - Noel Vaillant, Nomura International. Probability.net

- "A billion-dollar game for bond managers". Financial Times.

- John Hull and Alan White. "Valuing Credit Default Swaps I: No Counterparty Default Risk". Rotman School of Management at University of Toronto.

- Hull, J. C. and A. White, Valuing Credit Default Swaps II: Modeling Default Correlations. Smart Quant. Smartquant.com.

- Elton et al, Explaining the rate spread on corporate bonds. Stern.nyu.edu.

- Warren Buffett on Derivatives - Excerpts from the Berkshire Hathaway annual report for 2002.. Fintools.com.

- Roundtable on MiddleOffice - Hedge Fund Manager Week.

- The Real Reason for the Global Financial Crisis.Financial Sense. Financialsense.com.

- Demystifying the Credit Crunch. Private Equity Council.

- Sjostrom, Jr., William K., The AIG Bailout, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1346552 (2009). William K. Sjostrom

- Standard CDS Pricing Model Source Code - ISDA and Markit Group Limited. CDSModel.com

[edit] In the news

- July 21, 1997, BusinessWeek: "DIZZYING NEW WAYS TO DICE UP DEBT Suddenly, credit derivatives--deals that spread credit risk--are surging by Phillip L. Zweig

- October 8, 2008, New York Times: "the spectacular boom and calamitous bust in derivatives trading Taking Hard New Look at a Greenspan Legacy by Peter S. Goodman

- January 18, 2008, Wall Street Journal: "Default Fears Unnerve Markets" by Susan Pulliam and Serena Ng on CDS counterparty risk.

- February 5, 2008, Financial Times: "CDS market may create added risks" by Satayjit Das.

- February 17, 2008, New York Times: "Arcane Market is Next to Face Big Credit Test" By Gretchen Morgenson

- March 17, 2008 Credit Default Swaps: The Next Crisis?

- March 23, 2008, New York Times: "Who Created This Monster?" By Nelson D. Schwartz and Julie Creswell

- May 20, 2008, Bloomberg: "Hedge Funds in Swaps Face Peril With Rising Junk Bond Defaults" by David Evans.

- May 28, 2008, Financial Times: "Moody's issues warning on CDS risks" by Aline van Duyn.

- June 1, 2008, New York Times: "First Comes the Swap. Then It’s the Knives." by Gretchen Morgenson about a CDS dispute between UBS and Paramax Capital.

- September 18, 2008, Reuters: "Buffett's 'time bomb' goes off on Wall Street." by James B. Kelleher about credit default swaps turning a bad situation into a catastrophe.

- September 27, 2008, NYTimes: "Behind Insurer’s Crisis, Blind Eye to a Web of Risk" by Gretchen Morgenson.

- September 30, 2008, Fortune Magazine: "The $55 Trillion Question" by Nicholas Varchaver and Katie Benner on CDS spotlight during financial crisis.

- Dizard, John (2006-10-23). "A billion dollar game". Financial Times. http://us.ft.com/ftgateway/superpage.ft?news_id=fto102320061114181979. Retrieved on 2008-10-19.

- October 19, 2008, Portfolio.com: "Why the CDS Market Didn't Fail" Analyzes the CDS market's performance in the Lehman Bros. bankruptcy.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||