MD5

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| General | |

|---|---|

| Designers | Ron Rivest |

| First published | April 1992 |

| Series | MD, MD2, MD3, MD4, MD5, MD6 |

| Detail | |

| Digest sizes | 128 bits |

| Rounds | 4 |

In cryptography, MD5 (Message-Digest algorithm 5) is a widely used cryptographic hash function with a 128-bit hash value. As an Internet standard (RFC 1321), MD5 has been employed in a wide variety of security applications, and is also commonly used to check the integrity of files. However, it has been shown that MD5 is not collision resistant[1]; as such, MD5 is not suitable for applications like SSL certificates or digital signatures that rely on this property. An MD5 hash is typically expressed as a 32 digit hexadecimal number.

MD5 was designed by Ron Rivest in 1991 to replace an earlier hash function, MD4. In 1996, a flaw was found with the design of MD5. While it was not a clearly fatal weakness, cryptographers began recommending the use of other algorithms, such as SHA-1 (which has since been found vulnerable). In 2004, more serious flaws were discovered, making further use of the algorithm for security purposes questionable.[2][3] In 2007 a group of researchers including Arjen Lenstra described how to create a pair of files that share the same MD5 checksum.[4] In an attack on MD5 published in December 2008, a group of researchers used this technique to fake SSL certificate validity.[5][6]

Contents |

[edit] History and cryptanalysis

MD5 is one in a series of message digest algorithms designed by Professor Ronald Rivest of MIT (Rivest, 1994). When analytic work indicated that MD5's predecessor MD4 was likely to be insecure, MD5 was designed in 1991 to be a secure replacement. (Weaknesses were indeed later found in MD4 by Hans Dobbertin.)

In 1993, Den Boer and Bosselaers gave an early, although limited, result of finding a "pseudo-collision" of the MD5 compression function; that is, two different initialization vectors which produce an identical digest.

In 1996, Dobbertin announced a collision of the compression function of MD5 (Dobbertin, 1996). While this was not an attack on the full MD5 hash function, it was close enough for cryptographers to recommend switching to a replacement, such as SHA-1 or RIPEMD-160.

The size of the hash—128 bits—is small enough to contemplate a birthday attack. MD5CRK was a distributed project started in March 2004 with the aim of demonstrating that MD5 is practically insecure by finding a collision using a birthday attack.

MD5CRK ended shortly after 17 August, 2004, when collisions for the full MD5 were announced by Xiaoyun Wang, Dengguo Feng, Xuejia Lai, and Hongbo Yu.[2][7][3] Their analytical attack was reported to take only one hour on an IBM p690 cluster.

On 1 March 2005, Arjen Lenstra, Xiaoyun Wang, and Benne de Weger demonstrated[8] construction of two X.509 certificates with different public keys and the same MD5 hash, a demonstrably practical collision. The construction included private keys for both public keys. A few days later, Vlastimil Klima described[9] an improved algorithm, able to construct MD5 collisions in a few hours on a single notebook computer. On 18 March 2006, Klima published an algorithm[10] that can find a collision within one minute on a single notebook computer, using a method he calls tunneling.

[edit] Vulnerability

Because MD5 makes only one pass over the data, if two prefixes with the same hash can be constructed, a common suffix can be added to both to make the collision more reasonable.

Because the current collision-finding techniques allow the preceding hash state to be specified arbitrarily, a collision can be found for any desired prefix; that is, for any given string of characters X, two colliding files can be determined which both begin with X.

All that is required to generate two colliding files is a template file, with a 128-byte block of data aligned on a 64-byte boundary, that can be changed freely by the collision-finding algorithm.

Recently, a number of projects have created MD5 "rainbow tables" which are easily accessible online, and can be used to reverse many MD5 hashes into strings that collide with the original input, usually for the purposes of password cracking. However, if passwords are combined with a salt before the MD5 digest is generated, rainbow tables become much less useful.

The use of MD5 in some websites' URLs means that Google can also sometimes function as a limited tool for reverse lookup of MD5 hashes.[11] This technique is rendered ineffective by the use of a salt.

On December 30, 2008, a group of researchers announced at the 25th Chaos Communication Congress how they had used MD5 collisions to create an intermediate certificate authority certificate which appeared to be legitimate when checked via its MD5 hash.[5]. The researchers used a cluster of Sony Playstation 3s at the EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland.[12] to change a normal SSL certificate issued by RapidSSL into a working CA certificate for that issuer, which could then be used to create other certificates that would appear to be legitimate and issued by RapidSSL. VeriSign, the issuers of RapidSSL certificates, said they stopped issuing new certificates using MD5 as their checksum algorithm for RapidSSL once the vulnerability was announced.[13]

[edit] Applications

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2008) |

MD5 digests have been widely used in the software world to provide some assurance that a transferred file has arrived intact. For example, file servers often provide a pre-computed MD5 checksum for the files, so that a user can compare the checksum of the downloaded file to it. Unix-based operating systems include MD5 sum utilities in their distribution packages, whereas Windows users use third-party applications.

However, now that it is easy to generate MD5 collisions, it is possible for the person who created the file to create a second file with the same checksum, so this technique cannot protect against some forms of malicious tampering. Also, in some cases the checksum cannot be trusted (for example, if it was obtained over the same channel as the downloaded file), in which case MD5 can only provide error-checking functionality: it will recognize a corrupt or incomplete download, which becomes more likely when downloading larger files.

MD5 is widely used to store passwords[14][15][16]. To mitigate against the vulnerabilities mentioned above, one can add a salt to the passwords before hashing them. Some implementations may apply the hashing function more than once—see key strengthening.

[edit] Algorithm

![]() s denotes a left bit rotation by s places; s varies for each operation.

s denotes a left bit rotation by s places; s varies for each operation. ![]() denotes addition modulo 232.

denotes addition modulo 232.

MD5 processes a variable-length message into a fixed-length output of 128 bits. The input message is broken up into chunks of 512-bit blocks (sixteen 32-bit little endian integers); the message is padded so that its length is divisible by 512. The padding works as follows: first a single bit, 1, is appended to the end of the message. This is followed by as many zeros as are required to bring the length of the message up to 64 bits fewer than a multiple of 512. The remaining bits are filled up with a 64-bit integer representing the length of the original message, in bits.

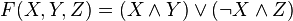

The main MD5 algorithm operates on a 128-bit state, divided into four 32-bit words, denoted A, B, C and D. These are initialized to certain fixed constants. The main algorithm then operates on each 512-bit message block in turn, each block modifying the state. The processing of a message block consists of four similar stages, termed rounds; each round is composed of 16 similar operations based on a non-linear function F, modular addition, and left rotation. Figure 1 illustrates one operation within a round. There are four possible functions F; a different one is used in each round:

denote the XOR, AND, OR and NOT operations respectively.

denote the XOR, AND, OR and NOT operations respectively.

[edit] Pseudocode

Pseudocode for the MD5 algorithm follows.

//Note: All variables are unsigned 32 bits and wrap modulo 2^32 when calculating var int[64] r, k //r specifies the per-round shift amounts r[ 0..15] := {7, 12, 17, 22, 7, 12, 17, 22, 7, 12, 17, 22, 7, 12, 17, 22} r[16..31] := {5, 9, 14, 20, 5, 9, 14, 20, 5, 9, 14, 20, 5, 9, 14, 20} r[32..47] := {4, 11, 16, 23, 4, 11, 16, 23, 4, 11, 16, 23, 4, 11, 16, 23} r[48..63] := {6, 10, 15, 21, 6, 10, 15, 21, 6, 10, 15, 21, 6, 10, 15, 21} //Use binary integer part of the sines of integers (Radians) as constants: for i from 0 to 63 k[i] := floor(abs(sin(i + 1)) × (2 pow 32)) //Initialize variables: var int h0 := 0x67452301 var int h1 := 0xEFCDAB89 var int h2 := 0x98BADCFE var int h3 := 0x10325476 //Pre-processing: append "1" bit to message append "0" bits until message length in bits ≡ 448 (mod 512) append bit /* bit, not byte */ length of unpadded message as 64-bit little-endian integer to message //Process the message in successive 512-bit chunks: for each 512-bit chunk of message break chunk into sixteen 32-bit little-endian words w[i], 0 ≤ i ≤ 15 //Initialize hash value for this chunk: var int a := h0 var int b := h1 var int c := h2 var int d := h3 //Main loop: for i from 0 to 63 if 0 ≤ i ≤ 15 then f := (b and c) or ((not b) and d) g := i else if 16 ≤ i ≤ 31 f := (d and b) or ((not d) and c) g := (5×i + 1) mod 16 else if 32 ≤ i ≤ 47 f := b xor c xor d g := (3×i + 5) mod 16 else if 48 ≤ i ≤ 63 f := c xor (b or (not d)) g := (7×i) mod 16 temp := d d := c c := b b := b + leftrotate((a + f + k[i] + w[g]) , r[i]) a := temp //Add this chunk's hash to result so far: h0 := h0 + a h1 := h1 + b h2 := h2 + c h3 := h3 + d var int digest := h0 append h1 append h2 append h3 //(expressed as little-endian)

//leftrotate function definition

leftrotate (x, c)

return (x << c) or (x >> (32-c));

Note: Instead of the formulation from the original RFC 1321 shown, the following may be used for improved efficiency (useful if assembly language is being used - otherwise, the compiler will generally optimize the above code. Since each computation is dependent on another in these formulations, this is often slower than the above method where the nand/and can be parallelised):

(0 ≤ i ≤ 15): f := d xor (b and (c xor d)) (16 ≤ i ≤ 31): f := c xor (d and (b xor c))

[edit] MD5 hashes

The 128-bit (16-byte) MD5 hashes (also termed message digests) are typically represented as a sequence of 32 hexadecimal digits. The following demonstrates a 43-byte ASCII input and the corresponding MD5 hash:

MD5("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog")

= 9e107d9d372bb6826bd81d3542a419d6

Even a small change in the message will (with overwhelming probability) result in a completely different hash, due to the avalanche effect. For example, adding a period to the end of the sentence:

MD5("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.")

= e4d909c290d0fb1ca068ffaddf22cbd0

The hash of the zero-length string is:

MD5("")

= d41d8cd98f00b204e9800998ecf8427e

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Xiaoyun Wang and Hongbo Yu: How to Break MD5 and Other Hash Functions. Retrieved July 27, 2008

- ^ a b Xiaoyun Wang, Dengguo Feng, Xuejia Lai, Hongbo Yu: Collisions for Hash Functions MD4, MD5, HAVAL-128 and RIPEMD, Cryptology ePrint Archive Report 2004/199, 16 Aug 2004, revised 17 Aug 2004. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ a b J. Black, M. Cochran, T. Highland: A Study of the MD5 Attacks: Insights and Improvements, March 3, 2006. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ Marc Stevens, Arjen Lenstra, Benne de Weger: Vulnerability of software integrity and code signing applications to chosen-prefix collisions for MD5, Nov 30, 2007. Retrieved Jul 27, 2008.

- ^ a b Sotirov, Alexander; Marc Stevens, Jacob Appelbaum, Arjen Lenstra, David Molnar, Dag Arne Osvik, Benne de Weger (2008-12-30). "MD5 considered harmful today". http://www.win.tue.nl/hashclash/rogue-ca/. Retrieved on 2008-12-30. Announced at the 25th Chaos Communication Congress.

- ^ Stray, Jonathan (2008-12-30). "Web browser flaw could put e-commerce security at risk". CNET.com. http://news.cnet.com/8301-1009_3-10129693-83.html. Retrieved on 2009-02-24.

- ^ Philip Hawkes and Michael Paddon and Gregory G. Rose: Musings on the Wang et al. MD5 Collision, 13 Oct 2004. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ Arjen Lenstra, Xiaoyun Wang, Benne de Weger: Colliding X.509 Certificates, Cryptology ePrint Archive Report 2005/067, 1 Mar 2005, revised 6 May 2005. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ Vlastimil Klima: Finding MD5 Collisions – a Toy For a Notebook, Cryptology ePrint Archive Report 2005/075, 5 Mar 2005, revised 8 Mar 2005. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ Vlastimil Klima: Tunnels in Hash Functions: MD5 Collisions Within a Minute, Cryptology ePrint Archive Report 2006/105, 18 Mar 2006, revised 17 Apr 2006. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ Steven J. Murdoch: Google as a password cracker, Light Blue Touchpaper Blog Archive, Nov 16, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ "Researchers Use PlayStation Cluster to Forge a Web Skeleton Key". Wired. 2008-12-31. http://blog.wired.com/27bstroke6/2008/12/berlin.html. Retrieved on 2008-12-31.

- ^ Callan, Tim (2008-12-31). "This morning's MD5 attack - resolved". Verisign. https://blogs.verisign.com/ssl-blog/2008/12/on_md5_vulnerabilities_and_mit.php. Retrieved on 2008-12-31.

- ^ FreeBSD Handbook, Security - DES, Blowfish, MD5, and Crypt[1]

- ^ RedHat Linux 8.0 Password Security [2]

- ^ Solaris 10 policy.conf(4) man page [3]

[edit] References

- Berson, Thomas A. (1992). "Differential Cryptanalysis Mod 232 with Applications to MD5". EUROCRYPT: 71–80. ISBN 3-540-56413-6.

- Bert den Boer; Antoon Bosselaers (1993). Collisions for the Compression Function of MD5. pp. 293–304. ISBN 3-540-57600-2.

- Hans Dobbertin, Cryptanalysis of MD5 compress. Announcement on Internet, May 1996 [4].

- Dobbertin, Hans (1996). "The Status of MD5 After a Recent Attack". CryptoBytes 2 (2). ftp://ftp.rsasecurity.com/pub/cryptobytes/crypto2n2.pdf.

- Xiaoyun Wang; Hongbo Yu (2005). "How to Break MD5 and Other Hash Functions". EUROCRYPT. ISBN 3-540-25910-4.

[edit] External links

| This article's external links may not follow Wikipedia's content policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links. |

- RFC 1321 The MD5 Message-Digest Algorithm

- W3C recommendation on MD5

- Two colliding PostScript files with the same size

- Two colliding executable files

- C++, Delphi, Java, JavaScript, Perl, PHP, and Python implementations of MD5

- Online MD5 hash generator

- File system-based MD5 tool

- MD5 Collision Generation

- qDecoder's C/C++ MD5 API — open source library

[edit] Test vectors

The NESSIE project test vectors for MD5

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||