Gulliver's Travels

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article is missing citations or needs footnotes. Please help add inline citations to guard against copyright violations and factual inaccuracies. (February 2009) |

| Gulliver's Travels | |

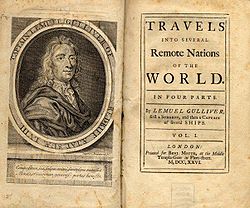

First Edition of Gulliver's Travels |

|

| Author | Jonathan Swift |

|---|---|

| Original title | Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of several Ships |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Satire |

| Publisher | Benjamin Motte |

| Publication date | 1726 |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | N/A |

Gulliver's Travels (1726, amended 1735), officially Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of several Ships, is a novel by Jonathan Swift that is both a satire on human nature and a parody of the "travellers' tales" literary sub-genre. It is Swift's best known full-length work, and a classic of English literature.

The book became tremendously popular as soon as it was published. (John Gay said in a 1726 letter to Swift that "it is universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery" [1] ); since then, it has never been out of print.

Contents |

[edit] Plot summary

The book presents itself as a simple traveller's narrative with the disingenuous title Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, its authorship assigned only to "Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, then a captain of several ships". Different editions contain different versions of the prefatory material which are basically the same as forewords in modern books. The book proper then is divided into four parts, which are as follows.

[edit] Part I: A Voyage to Lilliput

May 4, 1699 — April 13, 1702

The book begins with a short preamble in which Gulliver, in the style of books of the time, gives a brief outline of his life and history prior to his voyages. He enjoys travelling, although it is that love of travel that is his downfall.

On his first voyage, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck and awakes to find himself a prisoner of a race of people one-twelfth the size of normal human beings (6 inches/15cm tall), who are inhabitants of the neighbouring and rival countries of Lilliput and Blefuscu. After giving assurances of his good behaviour, he is given a residence in Lilliput and becomes a favourite of the court. From there, the book follows Gulliver's observations on the Court of Lilliput, which is intended to satirize the court of George I (King of England at the time of the writing of the Travels). Gulliver assists the Lilliputians to subdue their neighbours the Blefuscudians (by stealing their fleet). However, he refuses to reduce the country to a province of Lilliput, displeasing the King and the court. Gulliver is charged with treason and sentenced to be blinded. With the assistance of a kind friend, Gulliver escapes to Blefuscu, where he spots and retrieves an abandoned boat and sails out to be rescued by a passing ship which takes him back home. The feuding between the Lilliputians and the Blefuscudians is meant to represent the feuding countries of England and France, but the reason for the war – a disagreement over how to crack their eggs – is meant to satirize the absurdity and differences of the feud between Catholics and Protestants.

[edit] Part II: A Voyage to Brobdingnag

June 20, 1702 — June 3, 1706

When the sea vessel Adventure, which was an old wooden ship, is steered off course by storms and forced to go in to land for want of fresh water, Gulliver is abandoned by his companions and found by a farmer who is 72 feet (22 m) tall (the scale of Lilliput is approximately 1:12; of Brobdingnag 12:1, judging from Gulliver estimating a man's step being 10 yards (9.1 m)). He brings Gulliver home and his extremely smart and strong daughter cares for Gulliver. The farmer treats him as a curiosity and exhibits him for money. The word gets out and the Queen of Brobdingnag wants to see the show. She loves Gulliver and he is then bought by her and kept as a favourite at court.

Since Gulliver is too small to use their huge chairs, beds, knives and forks, the queen commissions a small house to be built for Gulliver so that he can be carried around in it. This box is referred to as his travelling box. In between small adventures such as fighting giant wasps and being carried to the roof by a monkey, he discusses the state of Europe with the King, who is not impressed. On a trip to the seaside, his "travelling box" is seized by a giant eagle which drops Gulliver and his box right into the sea where he is picked up by some sailors, who return him to England.

[edit] Part III: A Voyage to Laputa

August 5, 1706 — April 16, 1710

After Gulliver's ship is attacked by pirates, he is marooned near a desolate rocky island, near India. Fortunately he is rescued by the flying island of Laputa, a kingdom devoted to the arts of music and mathematics but utterly unable to use these for practical ends. The device described simply as The Engine is possibly the first literary description in history of something resembling a computer. Laputa's method of throwing rocks at rebellious surface cities also seems the first time that aerial bombardment was conceived as a method of warfare. While there, he tours the country as the guest of a low-ranking courtier and sees the ruin brought about by blind pursuit of science without practical results in a satire on the Royal Society and its experiments. He travels to a magician's dwelling and discusses history with the ghosts of historical figures, the most obvious restatement of the "ancients versus moderns" theme in the book. He also encounters the struldbrugs, unfortunates who are immortal and very, very old. Gulliver is then taken to Balnibarbi to await a Dutch trader who can take him on to Japan.The trip is otherwise reasonably free of incident and Gulliver returns home, determined to stay there for the rest of his days.

[edit] Part IV: A Voyage to the Country of the Houyhnhnms

September 7, 1710 – July 2, 1715

Despite his earlier intention of remaining at home, Gulliver returns to sea as a captain. On this voyage he is forced to find new additions to his crew who he believes to have turned the rest of the crew against him. His crew then mutiny and after keeping him contained for some time resolve to leave him on the first piece of land they come across and continue on as pirates. He is abandoned in a landing boat and comes first upon a race of (apparently) hideous deformed creatures to which he conceives a violent antipathy. Shortly thereafter he meets a horse and comes to understand that the horses (in their language Houyhnhnm or "the perfection of nature") are the rulers and the deformed creatures ("Yahoos") are human beings in their base form. Gulliver becomes a member of the horse's household, and comes to both admire and emulate the Houyhnhnms and their lifestyle, rejecting humans as merely Yahoos endowed with some semblance of reason which they only use to exacerbate and add to the vices Nature gave them. However, an Assembly of the Houyhnhnms rules that Gulliver, a Yahoo with some semblance of reason, is a danger to their civilization and he is expelled. He is then rescued, against his will, by a Portuguese ship, and is surprised to see that the captain, a Yahoo, is a wise, courteous and generous person. He returns to his home in England. However, he is unable to reconcile himself to living among Yahoos; he becomes a recluse, remaining in his house, largely avoiding his family and his wife, and spending several hours a day speaking with the horses in his stables.

[edit] Composition and history

It is uncertain exactly when Swift started writing Gulliver's Travels, but some sources suggest as early as 1713 when Swift, Gay, Pope, Arbuthnott and others formed the Scriblerus Club, with the aim of satirising then-popular literary genres. Swift, runs the theory, was charged with writing the memoirs of the club's imaginary author, Martinus Scriblerus. It is known from Swift's correspondence that the composition proper began in 1720 with the mirror-themed parts I and II written first, Part IV next in 1723 and Part III written in 1724, but amendments were made even while Swift was writing Drapier's Letters. By August 1725 the book was completed, and as Gulliver's Travels was a transparently anti-Whig satire it is likely that Swift had the manuscript copied so his handwriting could not be used as evidence if a prosecution should arise (as had happened in the case of some of his Irish pamphlets). In March 1726 Swift travelled to London to have his work published; the manuscript was secretly delivered to the publisher Benjamin Motte, who used five printing houses to speed production and avoid piracy.[2] Motte, recognising a bestseller but fearing prosecution, simply cut or altered the worst offending passages (such as the descriptions of the court contests in Lilliput or the rebellion of Lindalino), added some material in defence of Queen Anne to book II, and published it anyway. The first edition was released in two volumes on October 26, 1726, priced 8s. 6d. The book was an instant sensation and sold out its first run in less than a week.

Motte published Gulliver's Travels anonymously and, as was often the way with fashionable works, several follow-ups (Memoirs of the Court of Lilliput), parodies (Two Lilliputian Odes, The first on the Famous Engine With Which Captain Gulliver extinguish'd the Palace Fire...) and "keys" (Gulliver Decipher'd and Lemuel Gulliver's Travels into Several Remote Regions of the World Compendiously Methodiz'd, the second by Edmund Curll who had similarly written a "key" to Swift's Tale of a Tub in 1705) were produced over the next few years. These were mostly printed anonymously (or occasionally pseudonymously) and were quickly forgotten. Swift had nothing to do with any of these and specifically disavowed them in Faulkner's edition of 1735. However, Swift's friend Alexander Pope wrote a set of five Verses on Gulliver's Travels which Swift liked so much that he added them to the second edition of the book, though they are not nowadays generally included.

[edit] Faulkner's 1735 edition

In 1735 an Irish publisher, George Faulkner, printed a complete set of Swift's works to date, Volume III of which was Gulliver's Travels. As revealed in Faulkner's "Advertisement to the Reader", Faulkner had access to an annotated copy of Motte's work by "a friend of the author" (generally believed to be Swift's friend Charles Ford) which reproduced most of the manuscript free of Motte's amendments, the original manuscript having been destroyed. It is also believed that Swift at least reviewed proofs of Faulkner's edition before printing but this cannot be proven. Generally, this is regarded as the editio princeps of Gulliver's Travels with one small exception, discussed below.

This edition had an added piece by Swift, A letter from Capt. Gulliver to his Cousin Sympson which complained of Motte's alterations to the original text, saying he had so much altered it that "I do hardly know mine own work" and repudiating all of Motte's changes as well as all the keys, libels, parodies, second parts and continuations that had appeared in the intervening years. This letter now forms part of many standard texts.

[edit] Lindalino

The short (five paragraph) episode in Part III, telling of the rebellion of the surface city of Lindalino against the flying island of Laputa, was an obvious allegory to the affair of Drapier's Letters of which Swift was proud. Lindalino represented Dublin and the impositions of Laputa represented the British imposition of William Wood's poor-quality copper currency. For uncertain reasons Faulkner had omitted this passage, either because of political sensitivities raised by being an Irish publisher printing an anti-English satire or possibly because the text he worked from didn't include the passage either. It wasn't until 1899 that the passage was finally included in a new edition of the Collected Works. Modern editions thus derive from the Faulkner edition with the inclusion of this 1899 addendum.

Isaac Asimov notes in The Annotated Gulliver that Lindalino is composed of double lins; hence, Dublin.

[edit] Major themes

Gulliver's Travels has been the recipient of several designations: from Menippean satire to a children's story, from proto-Science Fiction to a forerunner of the modern novel. Possibly one of the reasons for the book's classic status is that it can be seen as many things to many different people. Broadly, the book has three themes:

- a satirical view of the state of European government, and of petty differences between religions.

- an inquiry into whether men are inherently corrupt or whether they become corrupted.

- a restatement of the older "ancients versus moderns" controversy previously addressed by Swift in The Battle of the Books.

In terms of storytelling and construction the parts follow a pattern:

- The causes of Gulliver's misadventures become more malignant as time goes on - he is first shipwrecked, then abandoned, then attacked by strangers, then attacked by his own crew.

- Gulliver's attitude hardens as the book progresses — he is genuinely surprised by the viciousness and politicking of the Lilliputians but finds the behaviour of the Yahoos in the fourth part reflective of the behaviour of people.

- Each part is the reverse of the preceding part — Gulliver is big/small/sensible/ignorant, the countries are complex/simple/scientific/natural, forms of Government are worse/better/worse/better than England's.

- Gulliver's view between parts contrasts with its other coinciding part — Gulliver sees the tiny Lilliputians as being vicious and unscrupulous, and then the king of Brobdingnag sees Europe in exactly the same light. Gulliver sees the Laputians as unreasonable, and Gulliver's Houyhnhnm master sees humanity as equally so.

- Jonathan Swift wanted to contrast Lilliput and England by representing the Lilliputian government in a sort of utopian light. A Utopia is a society that has overcome violence and war. Although Lilliput does have conflicts throughout the story, their methods of dealing with the situations are based on common morality, based on human rights. Swift was contrasting that to semi-utopian aspects of England at the time, meaning that the people of England were kept unaware to their humans rights.

- No form of government is ideal — the simplistic Brobdingnagians enjoy public executions and have streets infested with beggars, the honest and upright Houyhnhnms who have no word for lying are happy to suppress the true nature of Gulliver as a Yahoo and equally unconcerned about his reaction to being expelled.

- Specific individuals may be good even where the race is bad — Gulliver finds a friend in each of his travels and, despite Gulliver's rejection of and horror toward all Yahoos, is treated very well by the Portuguese captain, Don Pedro, who returns him to England at the novel's end.

Of equal interest is the character of Gulliver himself — he progresses from a cheery optimist at the start of the first part to the pompous misanthrope of the book's conclusion and we may well have to filter our understanding of the work if we are to believe the final misanthrope wrote the whole work. In this sense Gulliver's Travels is a very modern and complex novel. There are subtle shifts throughout the book, such as when Gulliver begins to see all humans, not just those in Houyhnhnm-land, as Yahoos.

Despite the depth and subtlety of the book, it is often classified as a children's story because of the popularity of the Lilliput section (frequently bowdlerised) as a book for children. It is still possible to buy books entitled Gulliver's Travels which contain only parts of the Lilliput voyage.

[edit] Cultural influences

From 1738 to 1746, Edward Cave published in occasional issues of The Gentleman's Magazine semi-fictionalized accounts of contemporary debates in the two Houses of Parliament under the title of Debates in the Senate of Lilliput. The names of the speakers in the debates, other individuals mentioned, politicians and monarchs present and past, and most other countries and cities of Europe ("Degulia") and America ("Columbia") were thinly disguised under a variety of Swiftian pseudonyms. The disguised names, and the pretence that the accounts were really translations of speeches by Lilliputian politicians, were a reaction to a Parliamentary act forbidding the publication of accounts of its debates. Cave employed several writers on this series: William Guthrie (June 1738-Nov. 1740), Samuel Johnson (Nov. 1740-Feb. 1743), and John Hawkesworth (Feb. 1743-Dec. 1746).

The popularity of Gulliver is such that the term "Lilliputian" has entered many languages as an adjective meaning "small and delicate". There is even a brand of cigar called Lilliput which is, obviously, small. In addition to this there are a series of collectible model-houses known as "Lilliput Lane". The smallest light bulb fitting (5mm diameter) in the Edison screw series is called the "Lilliput Edison screw". In Dutch, the word "Lilliputter" is used for adults shorter than 1.30 meters. On the other side, "Brobdingnagian" appears in the Oxford English Dictionary as a synonym for "very large" or "gigantic".

In like vein, the term "yahoo" is often encountered as a synonym for "ruffian" or "thug".

In the discipline of computer architecture, the terms big-endian and little-endian are used to describe two possible ways of laying out bytes in memory; see Endianness. One of the satirical conflicts in the book is between two political parties of Lilliputians, some of whom who prefer cracking open their soft-boiled eggs from the little end, while others prefer the big end.

[edit] Allusions and references from other works

[edit] References

- Philip K. Dick's short story "Prize Ship" (1954) loosely referred to Gulliver's Travels[3]

- Salman Rushdie refers to a country called Lilliput-Belfuscu in his novel Fury.

- Hayao Miyazaki's anime film Laputa: Castle in the Sky is about a mythical flying island.

- Rutherford Calhoun, the fictional narrator of Charles R. Johnson's novel Middle Passage briefly alludes to the Brobdingnagians.

- In the 9th book of The Time Wars Series, Simon Hawke's "The Lilliput Legion" (1989), the protagonists meet Lemuel Gulliver and battle the titular army.[4]

- In Fahrenheit 451, Montag briefly reads a section of Gulliver's Travels to his wife, who insists that it makes no sense. The section read is "It is computed that eleven thousand persons have at several times suffered death rather than submit to break their eggs at the smaller end."

[edit] Sequels and imitations

- Many sequels followed the initial publishing of the Travels. The earliest of these was the Abbé Pierre Desfontaines' Le Nouveau Gulliver ou Voyages de Jean Gulliver, fils du capitaine Lemuel Gulliver (The New Gulliver, or the travels of John Gulliver, son of Captain Lemuel Gulliver), published in 1730. The author was also the first French translator of Swift's story.

- The Hungarian writer Frigyes Karinthy (1887-1938) wrote two novels in which a 20th-century Gulliver visits imaginary lands. One, Utazás Faremidóba (i.e. Voyage to Faremido), recounts a trip to a land with almost robot-like, metallic beings whose lives are ruled by science, not emotion, and who communicate through a language based on musical notes. The second, Capillaria, is a satirical comment on male-female relationships. It involves a trip by Gulliver to a world where all the intelligent beings are female, males being reduced to nothing more than their reproductive function.

- Soviet Ukrainian science fiction writer Vladimir Savchenko published Gulliver's Fifth Travel - The Travel of Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and Then a Captain of Several Ships to the Land of Tikitaks (Russian: Пятое путешествие Гулливера - Путешествие Лемюэля Гулливера, сначала хирурга, а потом капитана нескольких кораблей, в страну тикитаков) - a sequel to the original series in which Gulliver's role as a surgeon is more apparent. Tikitaks are people who inject the juice of a unique fruit to make their skin transparent, as they consider people with regular opaque skin secretive and ugly.

- Davy King's 1978 short story "The Woman Gulliver Left Behind" [1] is a sort of satirical feminist spin on the tale, telling it from the point of view of Gulliver's wife. Alison Fell's novel "The Mistress of Lilliput" does likewise: Mary Gulliver goes travelling herself.

- The British children's book Mr Majeika on the Internet (2001) by Humphrey Carpenter includes modernized parallels to the lands of the Lilliputians, Brobdingnagians, Laputans and Houyhnhnms.

- Adam Roberts novel Swiftly (2008) is set 120 years after Gulliver's time and shows a world where the inhabitants of Lilliput and Blefuscu are now slaves of the British, and the Brobdingnagians are allied to France in a war against Britain.

[edit] Uses of characters

[edit] Gulliver

- In Alan Moore's comic The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Gulliver was the unofficial leader of an early incarnation of the League which also included The Scarlet Pimpernel, Dr. Syn and Fanny Hill.

- The character of Gulliver appears in the Doctor Who story The Mind Robber, played by Bernard Horsfall. He speaks only dialogue from the original book (though some speeches are patched together from widely separated sections).

[edit] Lilliputians

- The novel Mistress Masham's Repose (1946) by T. H. White features descendants of Lilliputians that were captured and brought to England.

- The novel Castaways in Lilliput (1958) by Henry Winterfeld is about three normal-sized children who land in a modern version of Lilliput.

- The TV series The Return of the Antelope (Granada Television) centres around the adventures of three Lilliputian sailors shipwrecked in England. The series was subsequently made into the stories The Return of the Antelope (1985) and its sequels The Antelope Company Ashore (1986) and The Antelope Company at Large (1987), all by Willis Hall. Republished as The Secret Visitors, The Secret Visitors Take Charge, and The Secret Visitors Fight Back.

- The comic book series Fables (2002-) has a city called "Smalltown" which was founded by self-exiled Lilliputian soldiers. All small Fables (not just Lilliputians) have a tendency to refer to normal-sized people as "gullivers" or as being "gulliver-sized".

[edit] Houyhnhnms

- In John Myers Myers novel Silverlock, the protagonist, A. Clarence Shandon, encounters the Houyhnhnms and is dismissed by them as a Yahoo.

[edit] Adaptations

[edit] Literary abridgments

- "A Voyage to Lilliput" was adapted for inclusion in Andrew Lang's Blue Fairy Book

[edit] Music

- German composer Georg Philipp Telemann wrote a suite for two violins, the "Gulliver Suite." The five movements are "Intrada," "Chaconne of the Lilliputians," "Gigue of the Brobdingnagians," "Daydreams of the Laputians and their attendant flappers," and "Loure of the well-mannered Houyhnhnms & Wild dance of the untamed Yahoos." Telemann wrote his suite in 1728, only two years after the publication of Swift's novel.

- One of popular funk band No More Kings' most popular songs, "Leaving Lilliput", is a retelling of Gulliver's first voyage.

- In Sereno, an album by Spanish Pop singer Miguel Bosé, he has a song in reference to Gulliver titled Gullever.

[edit] Film, TV, and other adaptations

Gulliver's Travels has been adapted several times for film, television and radio:

- Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants: A French short silent adaptation directed by Georges Méliès.

- The New Gulliver (1935): Russian film by Aleksandr Ptushko about a Soviet schoolboy who dreams about ending up in Lilliput. Notable for its intricate puppetry and a decidedly strange twisting of Swift's tale in favour of Communist ideas. This was the first film to contain stop motion animation in nearly its entire running time.

- Gulliver's Travels (1939): animated feature produced by Fleischer Studios and Paramount Pictures as a response to the success of Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, directed by Dave Fleischer. The film is generally considered one of the best from The Golden Age of Hollywood animation, although it varies widely from the original novel. Fleischer used the rotoscope to animate the character of Gulliver, tracing from footage of a live actor. The film was a moderate success, and its Lilliputian characters appeared in their own cartoon short subjects. With the expiration of its copyright, this film has entered the public domain, and can be downloaded at no charge from the Prelinger Archive.[5]

- The Three Worlds of Gulliver (1960): The first live action adaptation of Gulliver's Travels, but also incorporating the stop motion animation of Ray Harryhausen (surprisingly, there is very little of this). It was directed by Jack Sher and starred Kerwin Mathews.

- The Adventures of Gulliver (1968): This animated series was directed by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera. Young Gary Gulliver, voiced by Jerry Dexter, searches for his missing father in the land of Lilliput.

- Gulliver's Travels (1977): Live action/animated musical film directed by Peter R. Hunt and starring Richard Harris featuring the Lilliput voyage only.

- Gulliver's Travels (1979) : Animated cartoon made in Australia that was seen on Famous Classic Tales on CBS. It starred Ross Martin as Lemuel Gulliver and features two voyages.

- Gulliver in Lilliput (1982): Live-action television miniseries starring Frank Finlay and Elisabeth Sladen. As the title suggests, only Gulliver's trip to Lilliput is dramatised, but within that limitation the production is quite faithful to Swift. This was produced in the UK by the BBC, scripted and directed by Barry Letts.

- Gulliver's Travels (1992): Animated television series starring the voice of Terrence Scammell.

- Gulliver's Travels (1996): Live-action television mini-series starring Ted Danson and Mary Steenburgen. In this version Dr. Gulliver has returned to his family from a long absence. The action shifts back and forth between flashbacks of his travels and the present where he is telling the story of his travels and has been committed to an asylum. It is notable for being one of the very few adaptations to feature all four voyages, and is considered the closest adaptation to the book despite taking several liberties, such as Gulliver not returning home between each part.

- "Gulliver's Travels" (1999): Radio drama adaption of Gulliver's adventures in Lilliput, produced by the Radio Tales series for National Public Radio.

- Albhutha Dweepu (2005) A Malayalam Movie based upon Gulliver's Travels, features Prithviraj and Mallika Kapoor in the prominent roles besides 300 dwarfs all through the movie. This movie was later dubbed to Tamil in 2007.

- Gulliver's Travels (2007) Theatrical adaptation of all four travels. Dramatised by Brian Wright, with music from David Stoll. Performed by Masque Youth Theater in Northampton.

- Gulliver's Travels (2010) Planned live-action version of Gulliver's adventures in Lilliput, starring Jack Black, also featuring James Corden, Catherine Tate and Jason Segel.

[edit] References

- ^ Gulliver's Travels: Complete, Authoritative Text with Biographical and Historical Contexts, Palgrave Macmillan 1995 (p. 21). The quote has been misattributed to Alexander Pope, who wrote to Swift in praise of the book just a day earlier.

- ^ Clive Probyn, ‘Swift, Jonathan (1667–1745)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2004)

- ^ Collected Short Stories of Philip K. Dick: Volume One, Beyond Lies The Wub, Philip K. Dick, 1999, Millennium, an imprint of Orion Publishing Group, London

- ^ The Lilliput Legion, Simon Hawke, 1989, Ace Books, New York, NY

- ^ Internet Archive: Details: Gulliver's Travels

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Gulliver's Travels |

[edit] Online Text

- Gulliver's Travels at Project Gutenberg

- Gulliver's Travels (Parts I and II) with illustrations at Project Gutenberg

- Gulliver's Travels, full text and audio.

- Annotated version of Gulliver's Travels

- RSS edition of the text

- Searchable version in multiple formats ( html, XML, opendocument ODF, pdf (landscape, portrait), plaintext, concordance ) SiSU

[edit] Film

- Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants at the Internet Movie Database

- Novyj Gulliver (1935) at the Internet Movie Database

- Gulliver's Travels (1939) at the Internet Movie Database

- Gulliver's Travels (1939) — The full feature film available for download at the Internet Archive

- The 3 Worlds of Gulliver at the Internet Movie Database

- Gulliver's Travels (1977) at the Internet Movie Database

- Gulliver in Lilliput at the Internet Movie Database

- Gulliver's Travels (TV series) at the Internet Movie Database

- Gulliver's Travels (1996)(TV)(Mini-series) at the Internet Movie Database

- Arpudha Theevu (2007) Tamil Movie based upon Gulliver's Travels

[edit] Other Information

- Gulliver's Travels: The Antithetical Structure

- The Gulliver Code - Gulliver's Secret Deciphered, by Alastair Sweeny

- Armagh Public Library: Home to the original Gulliver's travels