Lolita

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Lolita | |

Cover of the first edition (Olympia Press, Paris, 1955) |

|

| Author | Vladimir Nabokov |

|---|---|

| Country | Russia/USA |

| Language | English, Russian |

| Genre(s) | Tragicomedy, novel |

| Publisher | Olympia Press, G. P. Putnam's Sons, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Fawcett, Transworld (Corgi), Phaedra |

| Publication date | 1955 |

| Media type | print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 368 pp (recent paperback edition) |

| ISBN | ISBN 1-85715-133-X (recent paperback edition) |

Lolita (1955) is a novel by Vladimir Nabokov, first written in English and published in 1955 in Paris, later translated by the author into Russian and published in 1958 in New York. The book is both internationally famous for its innovative style and infamous for its controversial subject: the narrator and protagonist, Humbert Humbert, becomes obsessed with a 12-year-old girl named Dolores Haze.

After its publication, Lolita attained a classic status, becoming one of the best known and most controversial examples of 20th century literature. The name "Lolita" has entered pop culture to describe a sexually precocious young girl. The novel was adapted to film in 1962 and again in 1997.

Time Magazine included the novel in its TIME 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005.[1]

Contents |

[edit] Plot summary

Lolita is narrated by Humbert Humbert, a literary scholar born in 1910 in Paris, who is obsessed with what he refers to as "nymphets". This obsession with young girls appears to have been a result of his failure to consummate an affair with a childhood sweetheart, Annabel Leigh, before her premature death from typhus. Shortly before the start of World War II, Humbert leaves Paris for New York. In 1947, he moves to Ramsdale, a small New England town, to write. When the house he was promised burns down, he ends up at the door of Charlotte Haze, a widow, who has a sexually charged interpretation of taking in a lodger. As the two make their way through Mrs. Haze's tour of the house, Humbert rehearses different ways of turning her down, but then, after being led out into the garden, he spies Haze's 12-year-old daughter Dolores (variously referred to in the novel as Dolores, Dolly, Lolita, Lola, Lo, and L) sunbathing in the garden. Humbert, seeing Annabel Leigh in her, is instantly smitten with her and eagerly agrees to rent the room.

When Lolita is at summer camp, Mrs. Haze gives Humbert an ultimatum by letter that he must marry her (for she has fallen madly in love with him) or move out. He is horrified at first, but sees living with Lolita as his stepdaughter as a way to make her part of his living fantasy. Charlotte appears oblivious to Humbert's distaste for her and his lust for Lolita until she reads his diary. Horrified and humiliated, Charlotte decides to flee with her daughter, writing letters to Humbert, Lolita, and a strict boarding school for young ladies to which she apparently intends to send her daughter. Charlotte confronts Humbert when he returns home, ignoring his protests that the diary entries are just notes for a novel, and bolts from the house to post the letters. But upon crossing the street, she is struck and killed by a passing motorist. A child retrieves the letters and gives them to Humbert, who destroys them.

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp, telling her that her mother is desperately ill in a hospital, and takes her to The Enchanted Hunters, a hotel of regional repute, where he meets a strange man (later revealed to be Clare Quilty), who seems to know who he is. Humbert intends to use sleeping pills on Lolita, but they have little effect. Instead, she seduces Humbert, and he discovers that he is not her first lover, as she has had a sexual affair at summer camp. After leaving the hotel, Humbert tells the now-troublesome Lolita that her mother is dead. Alone and frightened, Lolita has no choice but to accept Humbert into her life on his terms.

Driving Lolita around the country in Charlotte's car, moving from state to state and motel to motel, Humbert bribes the girl for sexual favors; he falls genuinely in love with her, but is conscious that she is not attracted to him and shares none of his interests. Eventually, the two settle down in another New England town, Beardsley, with Humbert posing as Lolita's father and Lolita enrolled in a private girls' school where the headmistress views Humbert's possessive supervision as that of a strict, old-world European parent.

Humbert nevertheless is persuaded to allow Lolita to take part in a school theatrical club (extracting additional sexual favors from her in exchange for his permission). Ominously, the title of the play — The Hunted Enchanters — is an inversion of the name of the hotel where he first molested her. Lolita is enthusiastic about the play and is said to have impressed the playwright, who attended a rehearsal. But before opening night, she and Humbert have a ferocious argument, and she bolts from the house. Found by Humbert a few minutes later, Lolita declares that she wants to immediately leave town and resume their travels. Humbert is delighted, but increasingly guarded as they again drive westward, nagged by a feeling that they are being followed and that Lolita knows who the follower is. He is right. Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte's, the nephew of the local dentist in Ramsdale, and the author of the play being performed at Lolita's school, is himself a pedophile and amateur pornographer. He is tailing the couple in accordance with a secret plan of escape devised with Lolita. While Humbert becomes increasingly paranoid, Lolita becomes ill and recuperates in a nearby hospital. One night, she checks out with her "uncle", who has paid the hospital bill. Humbert, still clueless about the identity of Lolita's "abductor," makes farcical and frantic attempts to find them by inspecting various motel-register aliases, which have been laced by Quilty with insults and jokes flavored with literary allusions.

During this period, Humbert has a chaotic, two-year love-affair with a petite alcoholic named Rita who, at 30, is 10 years younger than he and a passable physical substitute for Lolita. By 1952, Humbert has settled down as a scholar at a small academic institute. One day, he receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is married, pregnant, and in desperate need of funds. Armed with a gun, Humbert, still driving Charlotte's car, visits his young obsession and gives her the money she was due from her mother's estate. He also asks her to leave with him, but she refuses. During their conversation, Lolita explains that her husband, a nearly deaf war-veteran and the father of her unborn child, was not her abductor, whereupon Humbert offers to give her all the money he has if she will reveal the man's identity. Lolita complies, saying that she had really loved Clare Quilty, but that he threw her out after she refused to perform in a pornographic film he was making.

Leaving Lolita forever, Humbert surprises Quilty at his mansion. Quilty goes mad when he sees Humbert's gun. After a mutually exhausting struggle for it, Quilty, now insane with fear, merely responds politely as Humbert repeatedly shoots him. He finally dies with a comical lack of interest, expressing his slight concern in an affected English accent. Humbert is left exhausted and disoriented. Arrested for murder, he writes the book he entitles Lolita or, The Confessions of a White Widowed Male, while awaiting trial. According to the novel's fictional "Foreword", Humbert dies of coronary thrombosis upon finishing his manuscript. Lolita dies, during childbirth, on Christmas Day, 1952.

[edit] Style and interpretation

The novel is a tragicomedy narrated by Humbert, who riddles the narrative with wordplay and his wry observations of American culture. His humor provides an effective counterpoint to the pathos of the tragic plot. The novel's flamboyant style is characterized by word play, double entendres, multilingual puns, anagrams, and coinages such as nymphet, a word that has since had a life of its own and can be found in most dictionaries, and the lesser used "faunlet".

Nabokov's Lolita is far from an endorsement of pedophilia, since it dramatizes the tragic consequences of Humbert's obsession with the young girl. Several times, Humbert begs the reader to understand that he is not proud of his union with Lolita, but is filled with remorse. At one point, he is listening to the sounds of children playing outdoors, and is stricken with guilt at the realization that he robbed Lolita of her childhood.

Some critics have accepted Humbert's version of events at face value. In 1959, novelist Robertson Davies excused the narrator entirely, writing that the theme of Lolita is "not the corruption of an innocent child by a cunning adult, but the exploitation of a weak adult by a corrupt child".

Most writers, however, have given less credit to Humbert and more to Nabokov's powers as an ironist. For Richard Rorty, in his famous interpretation of Lolita in Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, Humbert is a "monster of incuriosity". Nabokov himself described Humbert as "a vain and cruel wretch" and "a hateful person" (quoted in Levine, 1967).

Martin Amis, in his essay on Stalinism, Koba the Dread, proposes that Lolita is an elaborate metaphor for the totalitarianism that destroyed the Russia of Nabokov's childhood (though Nabokov states in his Afterword that he "[detests] symbols and allegories"). Amis interprets it as a story of tyranny told from the point of view of the tyrant. "Nabokov, in all his fiction, writes with incomparable penetration about delusion and coercion, about cruelty and lies", he says. "Even Lolita, especially Lolita, is a study in tyranny".

In 2003, Iranian expatriate Azar Nafisi published the memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran about a covert women's reading group. For Nafisi, the essence of the novel is Humbert's solipsism and his erasure of Lolita's independent identity. She writes: "Lolita was given to us as Humbert's creature [...] To reinvent her, Humbert must take from Lolita her own real history and replace it with his own [...] Yet she does have a past. Despite Humbert's attempts to orphan Lolita by robbing her of her history, that past is still given to us in glimpses".[citation needed]

One of the novel's early champions, Lionel Trilling, warned in 1958 of the moral difficulty in interpreting a book with so eloquent and so self-deceived a narrator: "we find ourselves the more shocked when we realize that, in the course of reading the novel, we have come virtually to condone the violation it presents [...] we have been seduced into conniving in the violation, because we have permitted our fantasies to accept what we know to be revolting".[citation needed]

[edit] Publication and reception

Due to its subject matter, Nabokov was unable to find an American publisher for Lolita after finishing it in 1953. After four refusals, he finally resorted to Olympia Press in Paris, September 1955. Although the first printing of 5,000 copies sold out, there were no substantial reviews. Eventually, at the end of 1955, Graham Greene, in an interview with the (London) Times, called it one of the best novels of 1955. This statement provoked a response from the (London) Sunday Express, whose editor called it "the filthiest book I have ever read" and "sheer unrestrained pornography." British Customs officers were then instructed by a panicked Home Office to seize all copies entering the United Kingdom. In December 1956 the French followed suit and the Minister of the Interior banned Lolita (the ban lasted for two years). Its eventual British publication by Weidenfeld & Nicolson caused a scandal which contributed to the end of the political career of one of the publishers, Nigel Nicolson.[2]

By complete contrast, American officials were initially nervous, but the first American edition was issued without problems by G.P. Putnam's Sons in 1958, and was a bestseller, the first book since Gone with the Wind to sell 100,000 copies in the first three weeks of publication.

Today, it is considered by many to be one of the finest novels written in the 20th century. In 1998, it was named the fourth greatest English language novel of the 20th century by the Modern Library. Nabokov rated the book highly himself. In an interview for BBC Television in 1962 he said,

Lolita is a special favourite of mine. It was my most difficult book — the book that treated of a theme which was so distant, so remote, from my own emotional life that it gave me a special pleasure to use my combinational talent to make it real.

Two years later, in 1964's interview for Playboy, he said,

I shall never regret Lolita. She was like the composition of a beautiful puzzle —its composition and its solution at the same time, since one is a mirror view of the other, depending on the way you look. Of course she completely eclipsed my other works —at least those I wrote in English: The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, Bend Sinister, my short stories, my book of recollections; but I cannot grudge her this. There is a queer, tender charm about that mythical nymphet.

At the same year, in the interview for Life, Nabokov was asked, "Which of your writings has pleased you most?" He answered,

I would say that of all my books Lolita has left me with the most pleasurable afterglow —perhaps because it is the purest of all, the most abstract and carefully contrived. I am probably responsible for the odd fact that people don't seem to name their daughters Lolita any more. I have heard of young female poodles being given that name since 1956, but of no human beings.

[edit] Sources and links

[edit] Links in Nabokov's work

In 1939, Nabokov wrote a novella Volshebnik (Волшебник) that was published only posthumously in 1986 in English translation as The Enchanter. It can be seen as an early version of Lolita but with significant differences: it takes place in Central Europe, and the protagonist is unable to consummate his passion with his stepdaughter, leading to his suicide. The theme of ephebophilia was already touched on by Nabokov in his short story A Nursery Tale, written in 1926. Also, in the 1932 Laughter in the Dark, Margot Peters is 16 and already had an affair when middle-aged Albinus is attracted to her.

In chapter three of the novel The Gift (written in Russian in 1935–1937) the similar gist of Lolita's first chapter is outlined to the protagonist Fyodor Cherdyntsev by his obnoxious landlord Shchyogolev as an idea of a novel he would write "if I only had the time": a man marries a widow only to gain access to her young daughter, who however resists all his passes. Shchyogolev says it happened "in reality" to a friend of his; it is made clear to the reader that it concerns himself and his stepdaughter Zina (fifteen at the time of marriage) who becomes the love of Fyodor's life and his child bride.

In April 1947 Nabokov wrote to Edmund Wilson: "I am writing ... a short novel about a man who liked little girls – and it's going to be called The Kingdom by the Sea..."[3] The work expanded into Lolita during the next eight years. Nabokov used the title A Kingdom by the Sea in his 1974 pseudo-autobiographic novel Look at the Harlequins! for a Lolita-like book written by the narrator who, in addition, travels with his teenage daughter Bel from motel to motel after the death of her mother; later, his fourth wife is Bel's look-alike and shares her birthday.

[edit] Allusions/references to other works

- Humbert Humbert's first love, Annabel Leigh, is named after the woman in the poem "Annabel Lee" by Edgar Allan Poe. In fact, their young love is described in phrases borrowed from Poe's poem. Nabokov originally intended Lolita to be called The Kingdom by the Sea,[4] drawing on the rhyme with Annabel Lee that was used in the first verse of Poe's work. The part of the beginning of chapter one — "Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, exhibit number one is what the seraphs, the misinformed, simple, noble-winged seraphs, envied. Look at this tangle of thorns" — is also a reference to the poem. ("With a love that the winged seraphs in heaven / Coveted her and me".)

- Humbert Humbert's double name recalls Poe's "William Wilson", a tale in which the main character is haunted by his doppelgänger, paralleling to the presence of Humbert's own doppelgänger, Clare Quilty. Humbert is not, however, his real name, but a chosen pseudonym.

- Humbert Humbert's field of expertise is French literature (one of his jobs is writing a series of educational works that compare French writers to English writers), and as such there are several references to French literature, including the authors Gustave Flaubert, Marcel Proust, François Rabelais, Charles Baudelaire, Prosper Mérimée, Remy Belleau and Pierre de Ronsard.

- In chapter 17 of Part I, Humbert quotes "to hold thee lightly on a gentle knee and print on thy soft cheek a parent's kiss" from Lord Byron's Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.

- In chapter 35 of Part II, Humbert's "death sentence" on Quilty parodies the rhythm and use of anaphora in T. S. Eliot' poem Ash Wednesday.

- The line "I cannot get out, said the starling" from Humbert's poem is taken from a passage in Laurence Sterne's A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, "The Passport, the Hotel De Paris".

[edit] Possible real-life prototype

According to Alexander Dolinin,[5] the prototype of Lolita was 11-year-old Florence Horner, kidnapped in 1948 by a 50-year-old mechanic Frank La Salle, who had caught her stealing a five-cent notebook. La Salle travelled with her over various states for 21 months and is believed to have raped her. He claimed that he was an FBI agent and threatened to “turn her in” for the theft and to send her to "a place for girls like you." The Horner case was not widely reported, but Dolinin adduces various similarities in events and descriptions.

The problem with this suggestion is that Nabokov had already used the same basic idea — that of a child molester and his victim booking into a hotel as man and daughter — in his then-unpublished 1939 work Volshebnik (Волшебник). This is not to say, however, that Nabokov could not have drawn on some details of the case in writing Lolita, and the La Salle case is mentioned explicitly in Chapter 33 of Part II:

Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?

[edit] Heinz von Eschwege's "Lolita"

German academic Michael Maar's book The Two Lolitas (ISBN 1-84467-038-4) describes his recent discovery of a 1916 German short story titled "Lolita" about a middle-aged man travelling abroad who takes a room as a lodger and instantly becomes obsessed with the preteen girl (also named Lolita) who lives in the same house. Maar has speculated that Nabokov may have had cryptomnesia (a "hidden memory" of the story that Nabokov was unaware of) while he was composing Lolita during the 1950s. Maar says that until 1937 Nabokov lived in the same section of Berlin as the author, Heinz von Eschwege (pen name: Heinz von Lichberg), and was most likely familiar with his work, which was widely available in Germany during Nabokov's time there.[6][7] The Philadelphia Inquirer, in the article "Lolita at 50: Did Nabokov take literary liberties?" says that, according to Maar, accusations of plagiarism should not apply and quotes him as saying: "Literature has always been a huge crucible in which familiar themes are continually recast... Nothing of what we admire in Lolita is already to be found in the tale; the former is in no way deducible from the latter." See also Jonathan Lethem in Harper's Magazine on this story.[8]

[edit] Nabokov's afterword

In 1956, Nabokov penned an afterword to Lolita ("On a Book Entitled Lolita") that was included in every subsequent edition of the book.

In the afterword, Nabokov wrote that "the initial shiver of inspiration" for Lolita "was somehow prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature's cage". Neither the article nor the drawing has been recovered.

In response to an American critic who characterized Lolita as the record of Nabokov's "love affair with the romantic novel", Nabokov wrote that "the substitution of 'English language' for 'romantic novel' would make this elegant formula more correct".

Nabokov concluded the afterword with a reference to his beloved first language, which he abandoned as a writer once he moved to the United States in 1940: "My private tragedy, which cannot, and indeed should not, be anybody's concern, is that I had to abandon my natural idiom, my untrammeled, rich, and infinitely docile Russian tongue for a second-rate brand of English".

[edit] Russian translation

Nabokov translated Lolita into Russian; the translation was published by Phaedra in New York in 1967.

The translation includes a "Postscriptum" in which Nabokov reconsiders his relationship with his native tongue. Referring to the afterword to the English edition, Nabokov states that only "the scientific scrupulousness led me to preserve the last paragraph of the American afterword in the Russian text..." He further explains that the "story of this translation is the story of a disappointment. Alas, that 'wonderful Russian language' which, I imagined, still awaits me somewhere, which blooms like a faithful spring behind the locked gate to which I, after so many years, still possess the key, turned out to be non-existent, and there is nothing beyond that gate, except for some burned out stumps and hopeless autumnal emptiness, and the key in my hand looks rather like a lock pick."

[edit] Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

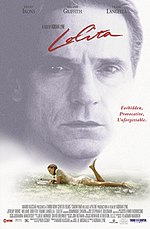

- Lolita has been filmed twice: the first adaptation was made in 1962 by Stanley Kubrick, and starred James Mason, Shelley Winters, Peter Sellers and, as Lolita, Sue Lyon; and a second adaptation in 1997 by Adrian Lyne, starring Jeremy Irons, Dominique Swain, and Melanie Griffith. Nabokov was nominated for an Academy Award for his work on the earlier film's adapted screenplay, although little of this work reached the screen. The more recent version was given mixed reviews by critics. It was delayed for over a year because of its controversial subject matter, and was not released in Australia until 1999.

- Nabokov's own version of the screenplay (dated Summer 1960 and revised December 1973) for Kubrick's film was published by McGraw-Hill in 1974.

- The book was adapted into a musical in 1971 by librettist/lyricist Alan Jay Lerner and composer John Barry under the title Lolita, My Love. Critics were surprised at how sensitively the story was translated to the stage, but the show nonetheless closed on the road before it opened in New York.[9]

- In 1982, Edward Albee adapted the book into a non-musical play. It was savaged by critics, Frank Rich notably attributing the temporary death of Albee's career to it.

- In 2003, Russian director Victor Sobchak wrote a second non-musical stage adaptation, which played in England at the Lion and Unicorn Fringe Theater in London. It drops the character of Quilty and updates the story to modern England.[10]

- The novel Lo's Diary by Pia Pera retells the novel from Lolita's point of view, making major plot changes on the premise that Humbert's version is incorrect on many points. Lolita is characterized as being herself quite sadistic and manipulative. [11]

- The poetry collection Poems for Men who Dream of Lolita by Kim Morrissey takes the form of a series of poems written by Lolita herself reflecting on the events in the story, a sort of diary in poetry form. In strong contrast to Pera's novel, Morrissey portrays Lolita as an innocent, wounded soul. Morrissey had earlier done a stage adaptation of Sigmund Freud's famous Dora case.[12]

- Sting & The Police released the song "Don't Stand So Close to Me" in 1993 on the album "Message in a Box", which contained numerous lyrical references to Lolita: "Just like the old man in / that famous book by Nabakov." The song portrays a romance between a teacher and an underage schoolgirl, much like Nabakov's novel.

- R. Schedrin adapted Lolita into a Russian language opera which premiered in Moscow in 2006 and was published that same year. It had a much earlier performance in Sweden in 1992. It was nominated for Russia's Golden Mask award.[13]

- The Boston-based composer John Harbison began an opera of Lolita which he abandoned in the wake of the clergy child-abuse scandal that rocked Boston. Fragments of what he had done were woven into seven-minute piece "Darkbloom: Overture for an Imagined Opera". Vivian Darkbloom, an anagram of Vladimir Nabokov, is a character in Lolita.[14]

- Steve Martin wrote a short story entitled "Lolita at Fifty" (included in his collection Pure Drivel), which is a gently humorous look at how Dolores Haze's life might have turned out.

- A loose adaption as an erotic film was done in Russian by Armen Oganezov in 2007 starring Valeria Nemchenko as Lolita, Marina Zasimova as her mother, and Vladimir Sorokin as the boarder. Supporting cast include Armen Oganezov, Natalia Belova, Daniela Torneva, Diana Sosnova, and Alice Vichkraft.

[edit] See also

- List of books portraying paedophilia or sexual abuse of minors

- List of films portraying paedophilia or sexual abuse of minors

[edit] Notes

- ^ http://www.time.com/time/2005/100books/the_complete_list.html

- ^ Laurence W. Martin, "The Bournemouth Affair: Britain's First Primary Election", The Journal of Politics, Vol. 22, No. 4. (Nov. 1960), pp. 654–681.

- ^ Letter dated April 7, 1947; in Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya: The Nabokov Wilson Letters, 1940–1971, ed. Simon Karlinsky (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001; ISBN 0-520-22080-3), p. 215

- ^ Brian Boyd on Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov Centennial, Random House, Inc.

- ^ Ben Dowell, "1940s sex kidnap inspired Lolita", The Sunday Times, September 11, 2005. Accessed on November 14, 2007.

- ^ On the Media, "My Sin, My Soul... Whose Lolita? ", September 16, 2005. Accessed on November 14, 2007.

- ^ Liane Hansen, "Possible Source for Nabokov's 'Lolita'", Weekend Edition Sunday, April 25, 2004. Accessed on November 14, 2007.

- ^ Jonathan Lethem, "The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism", Harper's Magazine, February 2007. Accessed on November 14, 2007.

- ^ broadwayworld.com Lolita, My Love

- ^ http://www.libraries.psu.edu/nabokov/vncol26.htm Accessed on March 13. 2008

- ^ http://www.nerve.com/Fiction/PeraPia/losDiary/ Accessed on March 13. 2008

- ^ http://members.aol.com/CanLit/Coteau/Morrissey/ Accessed on March 13. 2008

- ^ http://www.expat.ru/culturereviews.php?cid=48 Accessed on March 13. 2008

- ^ Daniel J. Wakin (March 24, 2005). "Wrestling With a 'Lolita' Opera and Losing". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/24/arts/music/24harb.html. Retrieved on 2008-03-13.

[edit] Further reading

- Appel, Alfred Jr. (1991). The Annotated Lolita (revised ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-72729-9.. One of the best guides to the complexities of Lolita. First published by McGraw-Hill in 1970. (Nabokov was able to comment on Appel's earliest annotations, creating a situation which Appel described as being like John Shade revising Charles Kinbote's comments on Shade's poem Pale Fire. Oddly enough, this is exactly the situation Nabokov scholar Brian Boyd proposed to resolve the literary complexities of Nabokov's Pale Fire.)

- Levine, Peter (1967). "Lolita and Aristotle's Ethics" in Philosophy and Literature Volume 19, Number 1, April 1995, pp. 32–47.

- Nabokov, Vladimir (1955). Lolita. New York: Vintage International. ISBN 0-679-72316-1. The original novel.

[edit] External links

- Photos of the first edition of Lolita

- Cover images of various editions

- Lolita USA: The itineraries of Humbert's and Lolita's two voyages across the U.S.A. 1947–1949, with maps and pictures.

- Lolita Calendar—A detailed and referenced inner chronology of Nabokov's novel.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||