Mathematical joke

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

This article or section has multiple issues. Please help improve the article or discuss these issues on the talk page.

|

A mathematical joke is a form of humor which relies on aspects of mathematics or a stereotype of mathematicians to derive humor. The humor may come from a pun, or from a double meaning of a mathematical term. It may also come from a lay person's misunderstanding of a mathematical concept (which is not wholly unexpected). These jokes are frequently inaccessible to those without a mathematical bent.

Contents |

[edit] Pun-based jokes

- Q. Why do mathematicians like national parks?

- A. Because of the natural logs.

- Q. What's purple and commutes ?

- A. An Abelian grape. (A pun on Abelian group.)[1]

A more sophisticated example:

- Person 1: What's the integral of 1/cabin?

- Person 2: A natural log cabin.

- Person 1: No, a houseboat – you forgot to add the c!

The first part of this joke relies on the fact that the primitive (formed when finding the antiderivative) of the function 1/x is ln(x). The second part is then based on the fact that the antiderivative is actually a class of functions, requiring the inclusion of a constant of integration, usually denoted as C — something which many calculus students forget. Thus, the indefinite integral of 1/cabin is "ln(cabin) + c", or "A natural log cabin plus the sea", ie. "A houseboat".

[edit] Jokes with numeral bases

- There are only 10 types of people in the world —

those who understand binary, and those who don't.

This joke relies on the fact that mathematical expressions, just as expressions in natural languages, may have multiple meanings. When multiple meanings are available, puns are possible. In this case a pun is made using the expression 10. For non-mathematicians or non-computer programmers 10 almost always refers to the number ten. However, in binary, the expression 10 means the number two. Thus the joke says that there are only two kinds of people, those who understand binary, and those who don't. However, those who do not understand binary will certainly not get the joke. This joke is only feasible in written form; when speaking a binary number aloud, "10" would be phrased as "one zero" or simply "two", rather than "ten".

This joke produced a number of similar ones, such as:

- There are only 10 types of people in the world —

those who understand ternary, those who don't, and those who mistake it for binary.

A similar joke may be played by asking the question:

- If only DEAD people understand hexadecimal, how many people understand hexadecimal?

- 57005.

In this case, DEAD refers to a hexadecimal number (57005 base 10), not the state of being no longer alive.

Another pun using different radices, sometimes attributed to computer scientists, asks:

The humor lies in the fact that Halloween occurs on October 31 and Christmas occurs on December 25, thus equating "oct" in October and octal, and "dec" in December and decimal. (This one is also often attributed to computer scientists: Real programmers confuse Halloween and Christmas — because dec(25) = oct(31).)

[edit] Stereotypes of mathematicians

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2009) |

Some jokes are based on stereotypes of mathematicians tending to think in complicated, abstract terms, causing them to lose touch with the "real world".

Many of these jokes compare mathematicians to other professions, typically physicists, engineers, or the "soft" sciences in a form similar to those which begin "An Englishman, an Irishman and a Scotsman…" or the like. The joke generally shows the other scientist doing something practical, while the mathematician does something less useful such as making the necessary calculation but not performing the implied action.

Examples:

- A mathematician and his best friend, an engineer, attend a public lecture on geometry in thirteen-dimensional space. "How did you like it?" the mathematician wants to know after the talk. "My head's spinning," the engineer confesses. "How can you develop any intuition for thirteen-dimensional space?" "Well, it's not even difficult. All I do is visualize the situation in n-dimensional space and then set n = 13."

- A physicist, a biologist and a mathematician are sitting in a street café watching people entering and leaving the house on the other side of the street. First they see two people entering the house. Time passes. After a while they notice three people leaving the house. The physicist says, "The measurement wasn't accurate." The biologist says, "They must have reproduced." The mathematician says, "If one more person enters the house then it will be empty."

An example of a joke relying on mathematicians' propensity for not taking the implied action is as follows:

- A mathematician, an engineer and a chemist are at a conference. They are staying in adjoining rooms. One evening they are downstairs in the bar. The mathematician goes to bed first. The chemist goes next, followed a minute or two later by the engineer. The chemist notices that in the corridor outside their rooms a rubbish bin is ablaze. There is a bucket of water nearby. The chemist starts concocting a means of generating carbon dioxide in order to create a makeshift extinguisher but before he can do so the engineer arrives, dumps the water on the fire and puts it out. The next morning the chemist and engineer tell the mathematician about the fire. She admits she saw it. They ask her why she didn't put it out. She replies contemptuously "there was a fire and a bucket of water: a solution obviously existed."

Mathematicians are also shown as averse to making sweeping generalizations from a small amount of data, preferring instead to state only that which can be logically deduced from the given information – even if some form of generalization seems plausible:

- An astronomer, a physicist and a mathematician are on a train in Scotland. The astronomer looks out of the window, sees a black sheep standing in a field, and remarks, "How odd. Scottish sheep are black." "No, no, no!" says the physicist. "Only some Scottish sheep are black." The mathematician rolls his eyes at his companions' muddled thinking and says, "In Scotland, there is at least one sheep, at least one side of which is black."

Another variant with cows was featured in the book The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time by Mark Haddon.

This is really a stereotype of a different group, but it seems to fit.

- What's the difference between a mathematician and a theoretical computer scientist?

- A mathematician can prove things without using induction.

[edit] Non-mathematician's math

The next category of jokes comprises those that exploit common misunderstandings of mathematics, or the expectation that most people have only a basic mathematical education, if any.

Examples:

- A visitor to the Royal Tyrrell Museum was admiring a Tyrannosaurus fossil, and asked a nearby museum employee how old it was. "That skeleton's sixty-five million three years, two months, and eighteen days old," the employee replied. "How can you know it that well?" she asked. "Well, when I started working here, I asked a scientist the exact same question, and he said it was sixty-five million years old – and that was three years, two months and eighteen days ago."

In the above example, the humor is that the employee fails to understand the scientist's implication of the uncertainty in the age of the fossil.

[edit] Mock mathematics

A form of mathematical humor comes from using mathematical tools (both abstract symbols and physical objects such as calculators) in various ways which transgress their intended ambit. These constructions are generally devoid of any "real" mathematics, besides some basic arithmetic.

[edit] Mock mathematical reasoning

A set of equivocal jokes applies mathematical reasoning to situations where it is not entirely valid. Many of these are based on a combination of well-known quotes and basic logical constructs such as syllogisms:

Example:

-

Premise I: Knowledge is power. Premise II: Power corrupts. Conclusion: Therefore, knowledge corrupts.

There are also a number of joke proofs, such as the proof that women are evil:

-

Women are the product of time and money:

Time is money: time = money So women are money squared: women = money2 Money is the root of all evil:

So women are evil:

Another set of jokes relate to the absence of mathematical reasoning, or misinterpretation of conventional notation:

Examples:

That is, the limit as x goes to 8 from above is a sideways 8 or the infinity sign, in the same way that the limit as x goes to three from above is a sideways 3 or the Greek letter omega.[2]

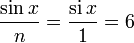

(That is, the "n" in "sin" cancels with the "n" in the denominator, giving "six" and 1 respectively.) See also Anomalous cancellation.

[edit] Calculator spelling

Tangential to mathematics is calculator spelling: words and phrases formed by entering a number and turning the calculator upside down. The words can be accompanied by stories involving numbers that lead to the "solution". A favorite word to spell is "hello", which is 0.1134 or 0.7734. Dropping the 0 and removing the decimal point results in "hell," another children's favorite.

A classical joke in Dutch is to ask a person the product of two times 36541867. The answer, 73083734 reads 'heleboel' (a whole lot) when turned upside down.[citation needed]

[edit] Math limericks

A math limerick is an expression which, when read aloud, matches the form of a limerick. The following example is attributed to Leigh Mercer:[3]

This is read as follows

- A dozen, a gross, and a score

- Plus three times the square root of four

- Divided by seven

- Plus five times eleven

- Is nine squared and not a bit more

[edit] See also

- Funny numbers

- Ralph P. Boas, Jr

- The Complexity of Songs

- Tom Lehrer's satirical songs "Lobachevsky" and "New Math".

- Proof by intimidation

- Spherical cow

[edit] Notes

- ^ Eric W. Weisstein, Abelian Group at MathWorld.

- ^ Xu, Chao (2008-02-21). "A mathematical look into the limit joke". http://mgccl.com/2008/02/21/a-mathematical-look-into-the-limit-joke. Retrieved on 2008-04-19.

- ^ Math Mayhem

[edit] Further reading

- Paul Renteln and Alan Dundes (2004-12-08). "Foolproof: A Sampling of Mathematical Folk Humor" (PDF). Notices of the AMS 52 (1). http://www.ams.org/notices/200501/fea-dundes.pdf.