Genetic programming

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In artificial intelligence, genetic programming (GP) is an evolutionary algorithm-based methodology inspired by biological evolution to find computer programs that perform a user-defined task. It is a specialization of genetic algorithms where each individual is a computer program. Therefore it is a machine learning technique used to optimize a population of computer programs according to a fitness landscape determined by a program's ability to perform a given computational task.

Contents |

[edit] History

The roots of GP begin with the evolutionary algorithms first utilized by Nils Aall Barricelli in 1954 as applied to evolutionary simulations. But evolutionary algorithms became widely recognized as optimization methods as a result of the work of Ingo Rechenberg in the 1960s and early 1970s - his group was able to solve complex engineering problems through evolution strategies (1971 PhD thesis and resulting 1973 book). Also highly influential was the work of John Holland in the early 1970s, and particularly his 1975 book.

The first results on the GP methodology were reported by Stephen F. Smith (1980)[1]. In 1981 Forsyth reported the evolution of small programs in forensic science for the UK police. The first statement of modern Genetic Programming (that is, procedural languages organized in tree-based structures and operated on by suitably defined GA-operators) was given by Nichael L. Cramer (1985),[2] and independently by Jürgen Schmidhuber(1987). This work was later greatly expanded by John R. Koza, a main proponent of GP who has pioneered the application of genetic programming in various complex optimization and search problems [3]. It should be noted that in his seminal work Koza (1992, see bibliography) posits GP as a generalization of genetic algorithms rather than a specialization.

GP is computationally very intensive and so in the 1990s it was mainly used to solve relatively simple problems. But more recently, thanks to improvements in GP technology and to the exponential growth in CPU power, GP produced many novel and outstanding results in areas such as quantum computing, electronic design, game playing, sorting, searching and many more.[4] These results include the replication or development of several post-year-2000 inventions. GP has also been applied to evolvable hardware as well as computer programs. There are several GP patents listed in the web site [5].

Developing a theory for GP has been very difficult and so in the 1990s GP was considered a sort of outcast among search techniques. But after a series of breakthroughs in the early 2000s, the theory of GP has had a formidable and rapid development. So much so that it has been possible to build exact probabilistic models of GP (schema theories and Markov chain models).[citation needed][dubious ]

[edit] Chromosome representation

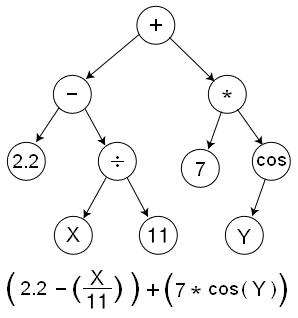

GP evolves computer programs, traditionally represented in memory as tree structures. Trees can be easily evaluated in a recursive manner. Every tree node has an operator function and every terminal node has an operand, making mathematical expressions easy to evolve and evaluate. Thus traditionally GP favors the use of programming languages that naturally embody tree structures (for example, Lisp; other functional programming languages are also suitable).

Non-tree representations have been suggested and successfully implemented, such as linear genetic programming which suits the more traditional imperative languages [see, for example, Banzhaf et al. (1998)]. The commercial GP software Discipulus,[6] uses AIM, automatic induction of binary machine code[7] to achieve better performance.[8] MicroGP[9] uses a representation similar to linear GP to generate programs that fully exploit the syntax of a given assembly language.

[edit] Genetic operators

The main operators used in evolutionary algorithms such as GP are crossover and mutation.

[edit] Crossover

Crossover is applied on an individual by simply switching one of its nodes with another node from another individual in the population. With a tree-based representation, replacing a node means replacing the whole branch. This adds greater effectiveness to the crossover operator. The expressions resulting from crossover are very much different from their initial parents.

The following code suggests a simple implementation of individual deformation using crossover:

individual.Children[randomChildIndex] = otherIndividual.Children[randomChildIndex];

[edit] Mutation

Mutation affects an individual in the population. It can replace a whole node in the selected individual, or it can replace just the node's information. To maintain integrity, operations must be fail-safe or the type of information the node holds must be taken into account. For example, mutation must be aware of binary operation nodes, or the operator must be able to handle missing values.

A simple piece of code:

individual. Information = randomInformation;

or

individual = generateNewIndividual;

there is an small mistake in this figure there we use LNR traversing so in the node (cos) the y child must be in the right side.

[edit] Meta-Genetic Programming

Meta-Genetic Programming is the proposed meta learning technique of evolving a genetic programming system using genetic programming itself. It suggests that chromosomes, crossover, and mutation were themselves evolved, therefore like their real life counterparts should be allowed to change on their own rather than being determined by a human programmer. Meta-GP was proposed by Jürgen Schmidhuber in 1987 [10]; it is a recursive but terminating algorithm, allowing it to avoid infinite recursion.

Critics of this idea often say this approach is overly broad in scope. However, it might be possible to constrain the fitness criterion onto a general class of results, and so obtain an evolved GP that would more efficiently produce results for sub-classes. This might take the form of a Meta evolved GP for producing human walking algorithms which is then used to evolve human running, jumping, etc. The fitness criterion applied to the Meta GP would simply be one of efficiency.

For general problem classes there may be no way to show that Meta GP will reliably produce results more efficiently than a created algorithm other than exhaustion. The same holds for standard GP and other search algorithms.

[edit] See also

- Bio-inspired computing

- Gene expression programming

- Genetic representation

- Grammatical evolution

- Genetic algorithms

- Fitness approximation

[edit] References and notes

- ^ Stephen F. Smith

- ^ Nichael Cramer's HomePage

- ^ genetic-programming.com-Home-Page

- ^ humancompetitive

- ^ jkpubs2001

- ^ Genetic Programming is a powerful regression and classification tool with significant advantages over neural networks, decision trees, support vector machines and robust regression. It is fast, powerful and has a proven track record of results

- ^ (Peter Nordin, 1997, Banzhaf et al., 1998, Section 11.6.2-11.6.3)

- ^ aigp3.dvi

- ^ Research: MicroGP

- ^ 1987 THESIS ON LEARNING HOW TO LEARN, METALEARNING, META GENETIC PROGRAMMING, CREDIT-CONSERVING MACHINE LEARNING ECONOMY

[edit] Bibliography

- Banzhaf, W., Nordin, P., Keller, R.E., Francone, F.D. (1998), Genetic Programming: An Introduction: On the Automatic Evolution of Computer Programs and Its Applications, Morgan Kaufmann

- Barricelli, Nils Aall (1954), Esempi numerici di processi di evoluzione, Methodos, pp. 45-68.

- Crosby, Jack L. (1973), Computer Simulation in Genetics, John Wiley & Sons, London.

- Cramer, Nichael Lynn (1985), "A representation for the Adaptive Generation of Simple Sequential Programs" in Proceedings of an International Conference on Genetic Algorithms and the Applications, Grefenstette, John J. (ed.), Carnegie Mellon University

- Fogel, David B. (2000) Evolutionary Computation: Towards a New Philosophy of Machine Intelligence IEEE Press, New York.

- Fogel, David B. (editor) (1998) Evolutionary Computation: The Fossil Record, IEEE Press, New York.

- Forsyth, Richard (1981), BEAGLE A Darwinian Approach to Pattern Recognition Kybernetes, Vol. 10, pp. 159-166.

- Fraser, Alex S. (1957), Simulation of Genetic Systems by Automatic Digital Computers. I. Introduction. Australian Journal of Biological Sciences vol. 10 484-491.

- Fraser, Alex and Donald Burnell (1970), Computer Models in Genetics, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Holland, John H (1975), Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

- Koza, J.R. (1990), Genetic Programming: A Paradigm for Genetically Breeding Populations of Computer Programs to Solve Problems, Stanford University Computer Science Department technical report STAN-CS-90-1314. A thorough report, possibly used as a draft to his 1992 book.

- Koza, J.R. (1992), Genetic Programming: On the Programming of Computers by Means of Natural Selection, MIT Press

- Koza, J.R. (1994), Genetic Programming II: Automatic Discovery of Reusable Programs, MIT Press

- Koza, J.R., Bennett, F.H., Andre, D., and Keane, M.A. (1999), Genetic Programming III: Darwinian Invention and Problem Solving, Morgan Kaufmann

- Koza, J.R., Keane, M.A., Streeter, M.J., Mydlowec, W., Yu, J., Lanza, G. (2003), Genetic Programming IV: Routine Human-Competitive Machine Intelligence, Kluwer Academic Publishers

- Langdon, W. B., Poli, R. (2002), Foundations of Genetic Programming, Springer-Verlag

- Nordin, J.P., (1997) Evolutionary Program Induction of Binary Machine Code and its Application. Krehl Verlag, Muenster, Germany.

- Poli, R., Langdon, W. B., McPhee, N. F. (2008). A Field Guide to Genetic Programming. Lulu.com, freely available from the internet. ISBN 978-1-4092-0073-4.

- Rechenberg, I. (1971): Evolutionsstrategie - Optimierung technischer Systeme nach Prinzipien der biologischen Evolution (PhD thesis). Reprinted by Fromman-Holzboog (1973).

- Schmidhuber, J. (1987). Evolutionary principles in self-referential learning. (On learning how to learn: The meta-meta-... hook.) Diploma thesis, Institut f. Informatik, Tech. Univ. Munich.

- Smith, S.F. (1980), A Learning System Based on Genetic Adaptive Algorithms, PhD dissertation (University of Pittsburgh)

- Smith, Jeff S. (2002), Evolving a Better Solution, Developers Network Journal, March 2002 issue

- Shu-Heng Chen et al. (2008), Genetic Programming: An Emerging Engineering Tool,International Journal of Knowledge-based Intelligent Engineering System, 12(1): 1-2, 2008.

[edit] External links

| This article's external links may not follow Wikipedia's content policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links. |

- A Field Guide to Genetic Programming by Poli, Langdon, and McPhee. Available as a free PDF, or in printed form from Lulu.com.

- Genetic Programming Source a website with a visual beginner's guide to GP.

- Aymen S Saket & Mark C Sinclair

- The Hitch-Hiker's Guide to Evolutionary Computation

- John Koza's Genetic Programming Site

- Jürgen Schmidhuber's GP Site, with pre-Koza GP papers (1987)

- Jürgen Schmidhuber's Meta-GP thesis (1987)

- GP bibliography

- People who work on GP

- Global Optimization Techniques and Genetic Programming Applied to Distributed Computing

Implementations:

- Genetic Programming in C++ A Simple implementation in C++

- pySTEP pySTEP or Python Strongly Typed gEnetic Programming

- Pyevolve (Python)

- Online moonlander demo (JavaScript)

- Demo applet of a genetic algorithm solving TSPs and VRPTW problems (.NET and Java)

- GP for the Optimization of the European Optical Network, Aymen Saket & Mark C Sinclair

- JAGA - Extensible and pluggable open source API for implementing genetic algorithms and genetic programming applications (Java)

- GPE - Framework for conducting experiments in Genetic Programming (.NET)

- lalena.com - A Genetic Program for simulating ant food collection behaviors. Free download (.NET)

- DGPF - simple Genetic Programming research system (Java)

- JGAP - Java Genetic Algorithms and Genetic Programming, an open-source framework (Java)

- n-genes - Java Genetic Algorithms and Genetic Programming (stack oriented) framework (Java)

- PMDGP - object oriented framework for solving genetic programming problems (C++)

- DRP - Directed Ruby Programming, Genetic Programming & Grammatical Evolution Library (Ruby)

- GPLAB - A Genetic Programming Toolbox for MATLAB (MATLAB)

- GPTIPS - Genetic Programming Tool for MATLAB - aimed at performing multigene symbolic regression (MATLAB)

- PyRobot - Evolutionary Algorithms (GA + GP) Modules, Open Source (Python)

- PerlGP - Grammar-based genetic programming in Perl (Perl)

- GAlib - Object oriented framework with 4 different GA implementations and 4 representation types (arbitrary derivations possible) (C++)

- Java GALib - Source Forge open source Java genetic algorithm library, complete with Javadocs and examples (see bottom of page) (Java)

- LAGEP. Supporting single/multiple population genetic programming to generate mathematical functions. Open Source, OpenMP used. (C/C++)

- PushGP, a strongly typed, stack-based genetic programming system that allows GP to manipulate its own code (auto-constructive evolution) (Lisp/C++/Javascript/Java)

- GPLib, a GP library from the University of Birmingham, UK (C++)

- Groovy Java Genetic Programming (Java)

- Progranisms, self copying/evolving programs

Possibly most used:

- ECJ - Evolutionary Computation/Genetic Programming research system (Java)

- Beagle - Open BEAGLE, a versatile EC framework (C++ with STL)

- EO Evolutionary Computation Framework (C++ with static polymorphism)

- GPC++ - Genetic Programming C++ Class Library (C++)