Individualist anarchism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. Please improve this article or discuss the issue on the talk page. |

| Individualism |

|

Individualist topics

Individualism · Individual rights · Individual sovereignty · Liberalism · Individualist anarchism

Existentialism · Capitalism Libertarianism · Liberty · Autonomy · Self-interest · Civil liberties · Private property · DIY · Workers' self-management · Objectivism · Methodological individualism · Ethical egoism |

|

Contrast

|

Individualist anarchism[ζ] refers to any of several traditions that hold that "individual conscience and the pursuit of self-interest should not be constrained by any collective body or public authority"[1] and that the imposition of "the system of democracy, of majority decision" over the decision of the individual "is held null and void."[2] Benjamin R. Tucker, a famous individualist anarchist described by leading European individualist and author of 'The Philosophy of Freedom' Rudolf Steiner as one of the best of libertarians (ref Liberty vol xiii, no 11), held that "if the individual has the right to govern himself, all external government is tyranny."[3]

Individualist anarchism is seen by many as one of two main categories or wings of anarchism – the other has been called social,[4] socialist,[5] collectivist,[6] or communitarian[7] anarchism.[α] One view is that the individualist wing of anarchism emphasises negative liberty, i.e. opposition to state or social control over the individual, while those in the collectivist wing emphasise positive liberty to achieve one's potential and argue that humans have needs that society ought to fulfill, "recognizing equality of entitlement".[8] Another distinction is that unlike the social wing which advocates common ownership as a means to eliminate unequal economic power, individualist anarchism is supportive of means of production being held privately, and in the case of the most prevalent strain of anarcho-individualism, advocates that goods and services be distributed through markets.[9] Moreover, they are not opposed to unequal wealth distribution, accepting this as a consequence of free competition.[10] In addition, unlike communist anarchism, anarcho-individualism is at best a philosophical/literary phenomenon rather than a being a social movement.[11] Philosophical anarchism, i.e. anarchism that does not advocate revolution to eliminate the state, "is a component especially of individualist anarchism."[12]

Individualist anarchism is not a single philosophy but refers to a group of individualistic philosophies; there are "several traditions of individualist anarchism."[13] Early individualist anarchists were motivated by progressive rationalism (in the case of William Godwin), Max Stirner's rational egoism, and Herbert Spencer's view that social evolution will render the state redundant.[β] Individualist forms of anarchism have appeared most often in the United States among such figures as Henry David Thoreau,[14][15] Josiah Warren, Benjamin Tucker, Lysander Spooner, Ezra Heywood, Stephen Pearl Andrews, and Murray Rothbard.[16] Notable contemporary individualist anarchists include Kevin Carson, Joe Peacott, Wendy McElroy, David D. Friedman, Robert Paul Wolff, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe. According to scholar Christopher Morris, individualist anarchism which supports a market society – ranging from that of Friedman and Rothbard to that of Tucker and Spooner – has had a greater level of revived interest, especially in the United States, than has communitarian anarchism, which is more widespread in Europe.[17]

Contents |

[edit] Overview

While individualist anarchists include William Godwin and Max Stirner,[18][19] most individualist anarchists are market anarchists in the American tradition,[dubious ] which advocate individual ownership of the produce of labor and a market economy where this property may be bought and sold. However, this form of individualist anarchism is not exclusive to the Americas; it is also found in the philosophy of other radical individualists, in places such as England and France—though almost all were influenced by the early American individualists.[citation needed] Individualist anarchism of this type contrasts with social anarchism which holds that productive property should be in the control of the society at large in various forms of worker collectives and that the produce of labor should be collectivized. Where individualist forms of anarchism emphasize personal autonomy and the rational nature of human beings, social anarchism sees individual liberty as being conceptually connected with social equality, emphasizing mutual aid.[20] However, it should be noted that some classical individualist anarchists, such as Benjamin Tucker, believed that people should not be allowed to own land in the full sense, but merely be allowed to use or occupy it. Some of the 19th century individualists called themselves socialists, such as Tucker who said, "the bottom claim of Socialism....[is that] labour should be put in possession of its own"[21] and that unlike the "to each according to his needs" credo of collectivists, individualist anarchism would be based on the ethic "renumeration to each according to the time spent in producing, while taking into account the productivity of his labour."[22] Individualist anarchist Joseph Labadie defined socialism this way: "which has for its object the changing of the present status of property and the relations one person or class holds to another. In other words, any movement which has for its aim the changing of social relations, of companionships, of associations, of powers of one class over another class, is Socialism."[23] These do not follow the most popular and well-known definition of socialism as community or state ownership, or objection to most private property. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon said "[m]odern Socialism was not founded as a sect or church; it has seen a number of different schools." [24]

Most of the individualist anarchists of the 19th and 18th centuries adhered to a labor theory of value, and therefore saw profit as unjust. However, there were radical individualists in the 19th and 18th centuries who did not adhere to a labor theory, among them Jakob Mauvillon, Julius Faucher, Gustave de Molinari, Auberon Herbert and Herbert Spencer. By the 20th century, when neoclassical economics had become dominant, many rejected the labor theory of value, especially its just price interpretation, for the mainstream marginal utility theory of value: Albert Jay Nock, Murray Rothbard and David D. Friedman being prime examples.

There is a pure egoist form of individualist anarchism, derived from the philosophy of Max Stirner, which supports the individual doing exactly what he pleases – taking no notice of God, state, or moral rules.[25] To Stirner, rights were spooks in the mind, and he held that society does not exist but "the individuals are its reality" – he supported property by force of might rather than moral right.[26] Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw "associations of egoists" drawn together by respect for each other's ruthlessness.[27] However, individualist anarchists are typically market anarchists, respecting the right of others to property. Their essential objection to the state is that it is a monopoly on the use of force in that it punishes those who would (personally, through mutual aid, or through contract) enforce their own rights, and because it requires purchase of that monopoly service through coercive taxation.[28] They believe that the institutions necessary for the function of a free market, which may include money, police, and courts, should be supplied by the market itself; beyond this guiding principle they are ideological diverse.

Individualist anarchists use the term "capitalism" in different ways: some, such as Josiah Warren, Benjamin Tucker, and Kevin Carson use "capitalism" to mean not the ownership of capital but the monopolization of it,[29][30] while others, such as Rothbard, Friedman, and Wendy McElroy define "capitalism" as a laissez-faire free market economy.[31][32] Anarcho-capitalism is a political philosophy that emerged in the middle of the 20th century, from the writings of Rothbard with his rejection of the nineteenth century individualists' labor theory of value. Agorism is a form of market anarchism popularized by the late Samuel Edward Konkin III, which emphasizes counter-economic activity, and is described by agorists as left-libertarian.[33] Anti-capitalist individualist anarchism declined through much of the twentieth century, but has recently aroused renewed interest.[γ]

Individualist anarchism is sometimes seen as an evolution of classical liberalism, and has consequently been referred to as "liberal anarchism".[34][35] Benjamin Tucker, for example, was influenced by Herbert Spencer, as he took up Spencer's "law of equal liberty."

[edit] Inspirations

[edit] William Godwin

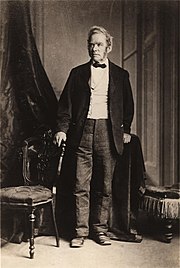

William Godwin was an individualist anarchist[36] and philosophical anarchist who was influenced by the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment,[37]and developed what many consider the first expression of modern anarchist thought.[18] Godwin was, according to Peter Kropotkin, "the first to formulate the political and economical conceptions of anarchism, even though he did not give that name to the ideas developed in his work."[38][39] Godwin advocated extreme individualism, proposing that all cooperation in labor be eliminated.[40] Godwin was a utilitarian who believed that all individuals are not of equal value, with some of us "of more worth and importance' than others depending on our utility in bringing about social good. Therefore he does not believe in equal rights, but the person's life that should be favored that is most conducive to the general good.[41] Godwin opposed government because it infringes on the individual's right to "private judgement" to determine which actions most maximize utility, but also makes a critique of all authority over the individual's judgement. This aspect of Godwin's philosophy, minus the utilitarianism, was developed into a more extreme form later by Stirner.[42]

Godwin's individualism was to such a radical degree that he even opposed individuals performing together in orchestras, writing in Political Justice that "everything understood by the term co-operation is in some sense an evil."[40] The only apparent exception to this opposition to cooperation is the spontaneous association that may arise when a society is threatened by violent force. One reason he opposed cooperation is he believed it to interfere with an individual's ability to be benevolent for the greater good. Godwin opposes the idea of government, but wrote that a minimal state as a present "necessary evil"[43] that would become increasingly irrelevant and powerless by the gradual spread of knowledge.[18] He expressly opposed democracy, fearing oppression of the individual by the majority (though he believed democracy to be preferable to dictatorship).

Godwin supported individual ownership of property, defining it as "the empire to which every man is entitled over the produce of his own industry."[43] However, he also advocated that individuals give to each other their surplus property on the occasion that others have a need for it, without involving trade (e.g. gift economy). Thus, while people have the right to private property, they should give it away as enlightened altruists. This was to be based on utilitarian principles; he said: "Every man has a right to that, the exclusive possession of which being awarded to him, a greater sum of benefit or pleasure will result than could have arisen from its being otherwise appropriated."[43] However, benevolence was not to be enforced, being a matter of free individual "private judgement." He did not advocate a community of goods or assert collective ownership as is embraced in communism, but his belief that individuals ought to share with those in need was influential on the later development of anarchist communism.

Godwin's political views were diverse and do not perfectly agree with any of the ideologies that claim his influence; writers of the Socialist Standard, organ of the Socialist Party of Great Britain, consider Godwin both an individualist and a communist;[44] anarcho-capitalist Murray Rothbard did not regard Godwin as being in the individualist camp at all, referring to him as the "founder of communist anarchism";[45] and historian Albert Weisbord considers him an individualist anarchist without reservation.[34] Some writers see a conflict between Godwin's advocacy of "private judgement" and utilitarianism, as he says that ethics requires that individuals give their surplus property to each other resulting in an egalitarian society, but, at the same time, he insists that all things be left to individual choice.[18] Many of Godwin's views changed over time, as noted by Peter Kropotkin.

[edit] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865) was the first philosopher to label himself an "anarchist."[46] Some consider Proudhon to be an individualist anarchist,[47][48][49] while others regard him to be a social anarchist.[50][51] Some commentators do not identify Proudhon as an individualist anarchist due to his preference for association in large industries, rather than individual control.[52] Nevertheless, he was influential among some of the American individualists; in the 1840s and 1850s, Charles A. Dana,[53] and William B. Greene introduced Proudhon's works to the United States. Greene adapted Proudhon's mutualism to American conditions and introduced it to Benjamin R. Tucker.[54]

Proudhon opposed government privilege that protects capitalist, banking and land interests, and the accumulation or acquisition of property (and any form of coercion that led to it) which he believed hampers competition and keeps wealth in the hands of the few. Proudhon favoured a right of individuals to retain the product of their labor as their own property, but believed that any property beyond that which an individual produced and could possess was illegitimate. Thus, he saw private property as both essential to liberty and a road to tyranny, the former when it resulted from labor and was required for labor and the latter when it resulted in exploitation (profit, interest, rent, tax). He generally called the former "possession" and the latter "property." For large-scale industry, he supported workers associations to replace wage labour and opposed the ownership of land.

Proudhon maintained that those who labor should retain the entirety of what they produce, and that monopolies on credit and land are the forces that prohibit such. He advocated an economic system that included private property as possession and exchange market but without profit, which he called mutualism. It is Proudhon's philosophy that was explicitly rejected by Joseph Dejacque in the inception of anarchist-communism, with the latter asserting directly to Proudhon in a letter that "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature." An individualist rather than anarchist communist,[55][56][57] Proudhon said that "communism...is the very denial of society in its foundation..."[58] and famously declared that "property is theft!" in reference to his rejection of ownership rights to land being granted to a person who is not using that land.

After Dejacque and others split from Proudhon due to the latter's support of individual property and an exchange economy, the relationship between the individualists, who continued in relative alignment with the philosophy of Proudhon, and the anarcho-communists was characterised by various degrees of antagonism and harmony. For example, individualists like Tucker on the one hand translated and reprinted the works of collectivists like Mikhail Bakunin, while on the other hand rejected the economic aspects of collectivism and communism as incompatible with anarchist ideals.

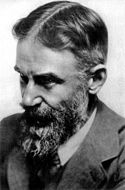

[edit] Max Stirner's "egoism"

Max Stirner's philosophy, sometimes called "egoism," is the most extreme[59] form of individualist anarchism. Max Stirner was a Hegelian philosopher whose "name appears with familiar regularity in historically-orientated surveys of anarchist thought as one of the earliest and best-known exponents of individualist anarchism."[19] In 1844, his The Ego and Its Own (Der Einzige and sein Eigentum which may literally be translated as The Unique Individual and His Property[60]) was published, which is considered to be "a founding text in the tradition of individualist anarchism."[19] Stirner does not recommend that the individual try to eliminate the state but simply that they disregard the state when it conflicts with one's autonomous choices and go along with it when doing so is conducive to one's interests.[61] He says that the egoist rejects pursuit of devotion to "a great idea, a good cause, a doctirine, a system, a lofty calling," saying that the egoist has no political calling but rather "lives themselves out" without regard to "how well or ill humanity may fare thereby."[62] Stirner held that the only limitation on the rights of the individual is his power to obtain what he desires.[63] He proposes that most commonly accepted social institutions—including the notion of State, property as a right, natural rights in general, and the very notion of society—were mere spooks in the mind. Stirner wants to "abolish not only the state but also society as an institution responsible for its members."[64] He advocated self-assertion and foresaw "associations of egoists" where respect for ruthlessness drew people together.[36] Even murder is permissible "if it is right for me."[65]

For Stirner, property simply comes about through might: "Whoever knows how to take, to defend, the thing, to him belongs property." And, "What I have in my power, that is my own. So long as I assert myself as holder, I am the proprietor of the thing." He says, "I do not step shyly back from your property, but look upon it always as my property, in which I respect nothing. Pray do the like with what you call my property!".[66] His concept of "egoistic property" not only a lack of moral restraint on how own obtains and uses things, but includes other people as well.[67] His embrace of egoism is in stark contrast to Godwin's altruism. Stirner was opposed to communism, seeing it as a form of authority over the individual.

This position on property is much different from the native American, natural law, form of individualist anarchism, which defends the inviolability of the private property that has been earned through labor[68] and trade. However, in 1886 Benjamin Tucker rejected the natural rights philosophy and adopted Stirner's egoism, with several others joining with him. This split the American individualists into fierce debate, "with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism itself."[69] Other egoists include James L. Walker, Sidney Parker, and Dora Marsden.

In Russia, individualist anarchism inspired by Stirner combined with an appreciation for Friedrich Nietzsche attracted a small following of bohemian artists and intellectuals such as Lev Chernyi, as well as a few lone wolves who found self-expression in crime and violence.[70] They rejected organizing, believing that only unorganized individuals were safe from coercion and domination, believing this kept them true to the ideals of anarchism.[71] This type of individualist anarchism inspired anarcho-feminist Emma Goldman[70]

Stirner's philosophy has also influenced some libertarian communists and anarcho-communists. "For Ourselves Council for Generalized Self-Management" discusses Stirner and speaks of a "communist egoism," which is said to be a "synthesis of individualism and collectivism," and says that "greed in its fullest sense is the only possible basis of communist society."[72] Forms of libertarian communism such as Situationism are strongly Egoist in nature.[73] Anarcho-communist Emma Goldman was influenced by both Stirner and Peter Kropotkin and blended their philosophies together in her own, as shown in books of hers such as Anarchism And Other Essays.[74]

[edit] Movements

[edit] Europe

Individualist anarchism was one of the three categories of anarchism in Russia, along with the more prominent anarchist communism and anarcho-syndicalism.[75] The ranks of the Russian individualist anarchists were predominantly drawn from the intelligentsia and the working class.[75]

| This section requires expansion. |

[edit] The American traditions

The American version of individualist anarchism has a strong emphasis on the non-aggression principle and individual sovereignty.[76] Some individualist anarchists, such as Henry David Thoreau[77][78], do not speak of economics but simply the right of "disunion" from the state, and foresee the gradual elimination of the state through social evolution. However, most of the individualists are market anarchists, and therefore support provision of defense of the individual and his property being supplied by multiple competing providers in a free market. Their doctrines may be seen as classical liberalism "taken to the extreme,"[79] stresses the importance of individual liberty, the sovereignty of the individual, private property or possession, and opposes all monopolies (which they believe can only arise through state intervention[80]).[79]

This may further be broadly divided into those who hold to a labor theory of value and those who do not. Some of the latter are often referred to as "anarcho-capitalists." Those referred to as 'anarcho-capitalists', do not oppose things such as profit, rent, loans or interest. They also do not object to workplace hierarchy or boss-worker economic relationship so long as such relationship is seen as non-coerced or in existence through non-aggression. Among the market anarchists, there is a strong advocacy of private property in the product of labor, and a competitive free market economy. Unlike social(ist) anarchists, individualists do not advocate the socialization or collectivization of the means or production.

An early individualist anarchist who was very influential was Josiah Warren, who had participated in a failed collective "utopian socialist" experiment headed by Robert Owen called "New Harmony" and came to the conclusion that such a system is inferior to one that respects the "sovereignty[81] of the individual" and his right to dispose of his property as his own self-interest prescribes. According to Warren, there should be absolutely no community of property; all property should be individualized, and "those who advocated any type of communism with connected property, interests, and responsibilities were doomed to failure because of the individuality of the persons involved in such as experiment."[82] In a much cited quotation from Practical Details, where he discusses his conclusions in regard to the experiment, he makes a vehement assertion of individual negative liberty:

| “ | Society must be so converted as to preserve the SOVEREIGNTY OF EVERY INDIVIDUAL inviolate. That it must avoid all combinations and connections of persons and interests, and all other arrangements which will not leave every individual at all times at liberty to dispose of his or her person, and time, and property in any manner in which his or her feelings or judgment may dictate, WITHOUT INVOLVING THE PERSONS OR INTERESTS OF OTHERS. | ” |

|

—Josiah Warren, Practical Details (1852).[83] |

||

Warren supported private property and trade. However, he held the labor theory of value, and from that he concluded that labor should always trade for an equal amount of labor. He believed that exchanges of unequal amounts of labor, or of goods that required unequal amounts of labor to produce, were always exploitative or unfair to the trader having to sacrifice more of his own labor than the other trader. His motto became "Cost the limit of price," with "cost" referring to the actual labor that was expended. He opposed what he called "value being made the limit of price," where individuals make exchanges of goods and services based on simply on how much they value what they are purchasing.[84] To ensure that labor received what he believed to be its just price—an equal amount of labor—he advocated that a form of money called "labor notes" be used, which represented labor times. In this way, labor would always be exchanged with an equal amount of labor and goods would always be purchased with an equal amount of labor that was exerted to produce those goods. But, he did not confine this to theory. He put labor notes into exercise in experimental communities which he set up.

[edit] The "Boston Anarchists"

Benjamin Tucker, and a series of other anarchists centered in the Boston area, were influenced by Warren and also a proponent of this interpretation of the labor theory of value. Tucker believed that it was unjust for individuals to receive greater income while performing less labor than others. Tucker asserted that the solution to bring wages up to be their proper level was for the state to cease interfering in the economy and protecting monopolies from competition. Like Warren, he saw income derived without labor to be exploitative (with the exception of gifts and inheritance[85]). He argued that lending money for interest involved no labor on the part of the lender and therefore saw interest charges as usurious. Rent was also seen as unjust because it involved obtaining an income without labor. To Tucker and most of his contemporary individualists, rent of land is only made possible by government-backed "monopoly" and "privilege" that restricts competition in the marketplace and concentrates wealth in the hands of a few. Tucker contended that private control of land should be supported only if the possessor of that land is using it, otherwise, the possessor would be able to charge rent to others without laboring to produce something. Tucker envisioned an individualist anarchist society as "each man reaping the fruits of his labour and no man able to live in idleness on an income from capital....become[ing] a great hive of Anarchistic workers, prosperous and free individuals [combining] to carry on their production and distribution on the cost principle."[86] However, not all of the early individualist anarchists held this philosophy of land ownership. Warren and Lysander Spooner placed no restrictions on occupancy and use for ownership. Steven T. Byington also opposed Tucker's ideas on occupancy and use requirements for land titles.[87]

Tucker and other nineteenth century individualists in his circle supported replacing the security functions of the state with private defense that charges for its services of protecting liberty and property. Benjamin Tucker says: :

| “ | "defense is a service like any other service; that it is labor both useful and desired, and therefore an economic commodity subject to the law of supply and demand; that in a free market this commodity would be furnished at the cost of production; that, competition prevailing, patronage would go to those who furnished the best article at the lowest price; that the production and sale of this commodity are now monopolized by the State; and that the State, like almost all monopolists, charges exorbitant prices"[88] | ” |

He said that anarchism "does not exclude prisons, officials, military, or other symbols of force. It merely demands that non-invasive men shall not be made the victims of such force. Anarchism is not the reign of love, but the reign of justice. It does not signify the abolition of force-symbols but the application of force to real invaders."[89] But Spooner argued that a society with unequal conditions would lead to a society of unfree associations. He argued for the right of everyone to hold land and have access to defence association[clarification needed], arguing that without such, "[a]ny number of scoundrels, having money enough to start with, can establish themselves as a 'government'; because, with money, they can hire soldiers, and with soldiers extort more money; and also compel general obedience to their will."[90] As far as a judicial system, many of these individualists such as Lysander Spooner supported a jury trial with the right of the jury to nullify law, "Honesty, justice, natural law, is usually a very plain and simple matter, . . . made up of a few simple elementary principles, of the truth and justice of which every ordinary mind has an almost intuitive perception,"[91] however some such as Steven T. Byington opposed such a system saying that there is a "need for certainty in some kinds of laws." Byington suggested that adjudications be done by judges "on a business basis" through private arbitration.[92]

Voltairine de Cleyre, summed up the philosophy by saying that the anarchist individualists "are firm in the idea that the system of employer and employed, buying and selling, banking, and all the other essential institutions of Commercialism, centered upon private property, are in themselves good, and are rendered vicious merely by the interference of the State."[93] According to Charles A. Madison, Stephen Pearl Andrews "spoke for all" of the nineteenth century individualist anarchists when he said, "It is right that one man employ another, it is right that he pay him wages, and it is right that he direct him absolutely, arbitrarily in the performance of labor."[94] Andrews said, "It is not in any, nor in all of these features combined, that the wrong of our present system is to be sought and found. It is in the simply failure to do Equity. It is not that men are employed and paid, but that they are not paid justly..."[95] For Andrews, to be paid justly was to be paid according to the "Cost Principle," which held that individuals should be paid according to the amount of labor they exert. To simplify this process, he, after Josiah Warren, advocated an economy that uses "labor notes." Labor notes are money marked in labor hours (adjusted for different types of labor based on their difficulty or repugnance). In this way, it is the amount, difficulty, and danger of labor that determines the pay of the employee, rather than the worth of the labor in the eyes of the employer.[96]

In regard to intellectual property there were varying opinions. "Spooner favored intellectual property laws, James L. Walker ("Tak Kak") opposed them, and others such as Tucker took an intermediate position that copyrights are legitimate only if created by contract."[97] Spooner's reasoning was that ideas are the product of "intellectual labor" and therefore private property.[98]

Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era, such as Benjamin Tucker, abandoned this form of anarchism and converted to Stirner's Egoism. Rejecting the idea of moral rights, Tucker said that there were only two rights, "the right of might" and "the right of contract." He also said, after converting to Egoist individualism, "In times past...it was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It was a bad habit, and I long ago sloughed it off....Man's only right to land is his might over it."[99]

Most early individualist anarchists, in the words of anarcho-communist writer L. Susan Brown, considered themselves "fervent anti-capitalists… [who saw] no contradiction between their individualist stance and their rejection of capitalism."'[100] These early individualist anarchists, however, defined "capitalism" as the state-maintained monopolization of capital.[101] Nevertheless, the early individualist anarchists did object to the profit-making aspect of capitalism, believing under the labor theory of value that making profit through capital was exploitative.[102] But, they would not forcibly prevent profit making, believing it to be freedom of contract. They simply thought that profit would be eliminated through competition if the state did not protect monopolies. Some of their descendents,[103] such as anarcho-capitalists,[103] do not agree with this prediction, as they believe labor theories of value to be fallacious and do not have an objection to profit regardless.

However, the individualist branch of Tucker did not consider themselves to be capitalistic, claiming "not Socialist Anarchism against Individualist Anarchism, but of Communist Socialism against Individualist Socialism."[104] John Beverly Johnson argued "[there] are two kinds of land ownership, proprietorship or property, by which the owner is absolute lord of the land, to use it or to hold it out of use, as it may please him; and possession, by which he is secure in the tenure of land which he uses and occupies, but has no claim upon it at all if he ceases to use it."[105] They believe that markets should be operated freely by property-owning workers, such as illustrated in his debate with Auberon Herbert, "When we come to the question of the ethical basis of property, Mr. Herbert refers us to 'the open market'. But this is an evasion. The question is not whether we should be able to sell or acquire 'in the open market' anything which we rightfully possess, but how we come into rightful possession."[106]

By the turn of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed,[107] Contemporary individualist anarchist Wendy McElroy suggests that the reason for the decline of individualist anarchism by the end of the twentieth century is that that the movement "hindered itself" and became "stagnant" by clinging to the labor theory of value and refusing to "incorporate the economic theories that were rising within other branches of Individualist thought, theories such as marginal utility."[108] Incorporation of these theories into individualist anarchism was not to occur until after the middle of the next century by Murray Rothbard, thus spurring a revival of anarchism of the individualist persuasion.

[edit] Anarcho-capitalism

19th century individualist anarchists espoused the labor theory of value. Some believe that the modern movement of anarcho-capitalism is the result of simply removing the labor theory of value from ideas of the 19th century American individualist anarchists: "Their successors today, such as Murray Rothbard, having abandoned the labor theory of value, describe themselves as anarcho-capitalists."[109] As economic theory changed, the popularity of the labor theory of classical economics was superseded by the subjective theory of value of neo-classical economics. According to Kevin Carson (himself a mutualist), "most people who call themselves "individualist anarchists" today are followers of Murray Rothbard's Austrian economics."[110]

Murray Rothbard, a student of Ludwig von Mises, combined the Austrian school economics of his teacher with the absolutist views of human rights and rejection of the state he had absorbed from studying the individualist American anarchists of the nineteenth century such as Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker.[111] In the winter of 1949, influenced by several nineteenth-century individualists anarchists, decided to reject minimal state laissez-faire and embrace individualist anarchism.[112] In 1965, Rothbard wrote:

| “ | Lysander Spooner and Benjamin T. Tucker were unsurpassed as political philosophers and nothing is more needed today than a revival and development of the largely forgotten legacy they left to political philosophy...There is, in the body of thought known as 'Austrian economics', a scientific explanation of the workings of the free market (and of the consequences of government intervention in that market) which individualist anarchists could easily incorporate into their political and social Weltanschauung. But to do this, they must throw out the worthless excess baggage of money-crankism and reconsider the nature and justification of the economic categories of interest, rent and profit.[113] | ” |

Anarcho-capitalists claim that in an anarcho-capitalist society no authority would prohibit anyone from providing, through the free market, services traditionally provided by state monopoly such as police, courts, and defense. Unlike the nineteenth century individualist anarchists,[110] they do not believe that there is anything unjust about individuals receiving more income with laboring less. As opposed to advocating "labor for labor" trade, as advocated by Tucker and others, they support trade "on the basis of value for value."[114] Moreover, unlike Tucker, they do not see any reason why labor costs would match up in a free market in the first place (economics inclined anarcho-capitalists believe that prices correspond to marginal utility rather than labor). Anarcho-capitalism does not believe that laissez-faire would cause profit to disappear, nor does it consider profit, rent, interest to be exploitative but natural and beneficial.[115] Rothbard holds that land can only become property by using or occupying it (he does not require that land be in continual use to remain owned), and that after this it can only legitimately change hands by trade or gift.[116] Anarcho-capitalists support the liberty of individuals to be self-employed or to contract to be employees of others, whichever they prefer. David Friedman has expressed preference for a society where "almost everyone is self-employed."[117] Anarcho-capitalism's leading proponents are Murray Rothbard and David D. Friedman and it has been influenced by non-anarchist libertarians such as Frederic Bastiat and Robert Nozick, and also by Ayn Rand (although she rejected both libertarianism and anarchism)

Rothbard wrote,

| “ | I am...strongly tempted to call myself an 'individualist anarchist', except for the fact that Spooner and Tucker have in a sense preempted that name for their doctrine and that from that doctrine I have certain differences. | ” |

Though anarcho-capitalism has been regarded as a form of individualist anarchism,[79][118] some writers, particularly anarcho-communists[119], deny that it is a form of anarchism,[120] or that capitalism itself is compatible with anarchism.[121]

[edit] Agorism

Agorism is a radical left-libertarian[δ] form of anarchism, developed from anarcho-capitalism in the late 20th-century by Samuel Edward Konkin III (a.k.a. SEK3). The goal of agorists is a society in which all "relations between people are voluntary exchanges – a free market."[33] Agorists are propertarian market anarchists who consider that property rights are natural rights deriving from the primary right of self-ownership and are not opposed in principle to collectively held property if individual owners of the property consent to collective ownership by contract or other voluntary mutual agreement. However, Agorists are divided on the question of intellectual property rights.[δ]

Agorists consider their ideas to be an evolution and superation of those of Murray Rothbard; Konkin described agorists as "strict Rothbardians…and even more Rothbardian than Rothbard."[122] The characteristic distinguishing it from other forms of market anarchism is its strategic emphasis on "counter-economics"—untaxed "black" market activity. Agorism advocates achieving a market anarchist society through advocacy and growth of the underground economy or "black market"—the "counter-economy" as Konkin put it. This process is intended to continue until the State's perceived moral authority and outright power have been so thoroughly undermined that revolutionary market anarchist legal and security enterprises are able to arise from underground and ultimately suppress government as a criminal activity. In this sense, agorism is "revolutionary market anarchism".[123]

[edit] Criticisms

Prior to abandoning anarchism, libertarian socialist Murray Bookchin criticized individualist anarchism for its opposition to democracy and its embrace of "lifestylism" at the expense of class struggle.[124] Bookchin claimed that individualist anarchism supports only negative liberty and rejects the idea of positive liberty.[125] Anarcho-communist Albert Meltzer proposed that individualist anarchism differs radically from revolutionary anarchism, and that it "is sometimes too readily conceded 'that this is, after all, anarchism'." He claimed that Benjamin Tucker's acceptance of the use of a private police force (including to break up violent strikes to protect the "employer's 'freedom'") is contradictory to the definition of anarchism as "no government."[126] Meltzer opposed anarcho-capitalism for similar reasons, arguing that since it supports "private armies", it actually supports a "limited State." He contends that it "is only possible to conceive of Anarchism which is free, communistic and offering no economic necessity for repression of countering it."[127]

According to Gareth Griffith, George Bernard Shaw initially had flirtations with individualist anarchism before coming to the conclusion that it was "the negation of socialism, and is, in fact, unsocialism carried as near to its logical conclusion as any sane man dare carry it." Shaw's argument was that even if wealth was initially distributed equally, the degree of laissez-faire advocated by Tucker would result in the distribution of wealth becoming unequal because it would permit private appropriation and accumulation.[128] According to academic Carlotta Anderson, American individualist anarchists accept that free competition results in unequal wealth distribution, but they "do not see that as an injustice."[129] Tucker explained, "If I go through life free and rich, I shall not cry because my neighbor, equally free, is richer. Liberty will ultimately make all men rich; it will not make all men equally rich. Authority may (and may not) make all men equally rich in purse; it certainly will make them equally poor in all that makes life best worth living."[130]

[edit] See also

[edit] Footnotes

α^ The term "individualist anarchism" is often used as a classificatory term, but in very different ways. Some sources, such as An Anarchist FAQ use the classification "social anarchism / individualist anarchism". Some see individualist anarchism as distinctly non-socialist, and use the classification "socialist anarchism / individualist anarchism" accordingly.[131] Other classifications include "mutualist/communal" anarchism.[132]

β^ Michael Freeden identifies four broad types of individualist anarchism. He says the first is the type associated with William Godwin that advocates self-government with a "progressive rationalism that included benevolence to others." The second type is the amoral self-serving rationality of Egoism, as most associated with Max Stirner. The third type is "found in Herbert Spencer's early predictions, and in that of some of his disciples such as Donisthorpe, foreseeing the redundancy of the state in the source of social evolution." The fourth type retains a moderated form of egoism and accounts for social cooperation through the advocacy of market relationships.[133]

γ^ See, for example, the Winter 2006 issue of the Journal of Libertarian Studies, dedicated to reviews of Kevin Carson's Studies in Mutualist Political Economy. Mutualists compose one bloc, along with agorists and geo-libertarians, in the recently formed Alliance of the Libertarian Left.

δ^ Though this term is non-standard usage – by "left", agorists mean "left" in the general sense used by left-libertarians, as defined by Roderick T. Long, as "... an integration, or I’d argue, a reintegration of libertarianism with concerns that are traditionally thought of as being concerns of the left. That includes concerns for worker empowerment, worry about plutocracy, concerns about feminism and various kinds of social equality."[134]

ε^ Konkin wrote the article "Copywrongs"in opposition to the concept and Schulman countered SEK3's arguments in "Informational Property: Logorights."

ζ^ Individualist anarchism is also known by the terms "anarchist individualism", "anarcho-individualism", "individualistic anarchism", "libertarian anarchism",[135][136][137][138] "anarcho-libertarianism",[139][140] "anarchist libertarianism"[139] and "anarchistic libertarianism".[141]

[edit] References

- ^ Heywood, Andrew (2000). Key Concepts in Politics. New York: Macmillan. p. 46. ISBN 0312233817.

- ^ Horowitz, The Anarchists (2005). Aldine Transaction. p. 49.

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin R. (March 10, 1888). "State Socialism and Anarchism: How far they agree and wherein they differ". Liberty 5 (16): 2-3, 6. http://praxeology.net/BT-SSA.htm.

- ^ Iain Mckay, ed (2008). An Anarchist FAQ. Stirling: AK Press. ISBN 1902593901. OCLC 182529204.

- ^ Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 14.

- ^ Morris, Christopher W. 1998. An Essay on the Modern State. Cambridge University Press. p 50 (uses "collectivist" and "communitarian" synonymously)

- ^ Wolff. Robert Paul. "Anarchism". The Oxford Companion to the Politics of the World, 2e. Joel Krieger, ed. Oxford University Press Inc. 2001. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press

- ^ Harrison, Kevin and Boyd, Tony. Understanding Political Ideas and Movements. Manchester University Press 2003, p. 251

- ^ Freeden, Micheal. Ideologies and Political Theory: A Conceptual Approach. Oxford University Press. p. 314. ISBN 019829414X.

- ^ Anderson, Carlotta R. (1998). All-American Anarchist: Joseph A. Labadie and the Labor Movement. Wayne State University Press. p. 250.

- ^ Skirda, Alexandre (2002). Facing the Enemy: A History of Anarchist Organization from Proudhon to May 1968. AK Press.

- '^ Outhwaite, William & Tourain, Alain, ed (2003). "Anarchism". The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought' (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing. p. 12.

- ^ Ward, Colin (2004). Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 2.

- ^ Johnson, Ellwood (2005). The Goodly Word: The Puritan Influence in America Literature. Clements Publishing. p. 138.

- ^ Edwin Robert Anderson Seligman, Alvin Saunders Johnson, ed (1937). Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences. p. 12.

- ^ Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America (abriged paperback ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1996. p. 282. ISBN 0691044945. OCLC 34193021. "Murray N. Rothbard (1926-1995), American economist, historian, and individualist anarchist"

- ^ Morris, Christopher. 1992. An Essay on the Modern State. Cambridge University Press. pp. 61 & 74.

- ^ a b c d William Godwin entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy by Mark Philip, 2006-05-20

- ^ a b c Max Stirner entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy by David Leopold, 2006-08-04

- ^ Suissa, Judith (2001). "Anarchism, Utopias and Philosophy of Education". Journal of Philosophy of Education 35 (4): 627–646. doi:.

- ^ The Individualist Anarchists, p. 78

- ^ The Conquest of Bread, p. 162

- ^ [Liberty, no. 158, p. 8]

- ^ [Selected Writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, p. 177]

- ^ Miller, David (1987). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 11.

- ^ "What my might reaches is my property; and let me claim as property everything I feel myself strong enough to attain, and let me extend my actual property as fas as I entitle, that is, empower myself to take…" From The Ego and Its Own, quoted in Ossar, Michael (1980). Anarchism in the Dramas of Ernst Toller. State University of New York Press. p. 27.

- ^ Woodcock, George (2004). Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Broadview Press. p. 20.

- ^ Drury, S.B.. "Robert Nozick And the Right to Property". in Parel, Anthony and Thomas Flanagan. Theories of Property: Aristotle to the Present: Essays. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 361.

- ^ Schwartzman, Jack. "Ingalls, Hanson, and Tucker: Nineteenth-Century American Anarchists". American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 62, No. 5 (November, 2003). p. 325

- ^ Carson, Kevin (2007). "Preface". Studies in Mutualist Political Economy. BookSurge Publishing. ISBN 1419658697.

- ^ McElroy, Wendy (12 June 2007). "Capitalism Versus the Free Market". WendyMcEllroy.com. http://www.wendymcelroy.com/news.php?extend.855. Retrieved on 2008-07-30.

- ^ Tormey, Simon (2004). Anti-Capitalism, A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications. pp. 118-119. "Pro-capitalist anarchism, is as one might expect, particularly prevalent in the U.S. where it feeds on the strong individualist and libertarian currents that have always been part of the American political imaginary. To return to the point, however, there are individualist anarchists who are most certainly not anti-capitalist and there are those who may well be."

- ^ a b Konkin III, Samuel Edward (2006) (PDF). New Libertarian Manifesto. KoPubCo. ISBN 0977764923. http://invisiblemolotov.files.wordpress.com/2008/06/new_libertarian_manifesto.pdf.

- ^ a b Weisbord, Albert (1937). "Libertarianism". The Conquest of Power. New York: Covici-Friede. OCLC 1019295.

- ^ Grant, Moyra (2003). Key Ideas in Politics. Nelson Thornes. p. 3. "Whereas collectivist anarchists derive their ideas from socialism, individualist anarchists derive their ideas largely from classical liberal thinking"

- ^ a b Woodcock, George. 2004. Anarchism: A History Of Libertarian Ideas And Movements. Broadview Press. p. 20

- ^ "Anarchism", Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006 (UK version)

- ^ Peter Kropotkin, "Anarchism", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1910

- ^ Godwin himself attributed the first anarchist writing to Edmund Burke's A Vindication of Natural Society. "Most of the above arguments may be found much more at large in Burke's Vindication of Natural Society; a treatise in which the evils of the existing political institutions are displayed with incomparable force of reasoning and lustre of eloquence…" – footnote, Ch. 2 Political Justice by William Godwin.

- ^ a b "Godwin, William". (2006). In Britannica Concise Encyclopaedia. Retrieved December 7, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ McLaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Ashgate Publishing,. p. 119.

- ^ McLaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Ashgate Publishing,. p. 123.

- ^ a b c Godwin, William (1796) [1793]. Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Modern Morals and Manners. G.G. and J. Robinson. OCLC 2340417.

- ^ "William Godwin, Shelly and Communism" by ALB, The Socialist Standard

- ^ Rothbard, Murray. "Edmund Burke, Anarchist."

- ^ "Anarchism", BBC Radio 4 program, In Our Time, Thursday December 7, 2006. Hosted by Melvyn Bragg of the BBC, with John Keane, Professor of Politics at University of Westminster, Ruth Kinna, Senior Lecturer in Politics at Loughborough University, and Peter Marshall, philosopher and historian.

- ^ George Edward Rines, ed (1918). Encyclopedia Americana. New York: Encyclopedia Americana Corp.. pp. 624. OCLC 7308909.

- ^ Hamilton, Peter (1995). Emile Durkheim. New York: Routledge. pp. 79. ISBN 0415110475.

- ^ Faguet, Emile (1970). Politicians & Moralists of the Nineteenth Century. Freeport: Books for Libraries Press. pp. 147. ISBN 0836918282.

- ^ Bowen, James & Purkis, Jon. 2004. Changing Anarchism: Anarchist Theory and Practice in a Global Age. Manchester University Press. p. 24

- ^ Knowles, Rob. "Political Economy from below : Communitarian Anarchism as a Neglected Discourse in Histories of Economic Thought". History of Economics Review, No.31 Winter 2000.

- ^ Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements, Broadview Press, 2004, p. 20

- ^ Dana, Charles A. Proudhon and his "Bank of the People" (1848).

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin R., "On Picket Duty", Liberty (Not the Daughter but the Mother of Order) (1881–1908); 5 January 1889; 6, 10; APS Online pg. 1

- ^ George Edward Rines, ed (1918). Encyclopedia Americana. New York: Encyclopedia Americana Corp.. pp. 624. OCLC 7308909.

- ^ Hamilton, Peter (1995). Emile Durkheim. New York: Routledge. pp. 79. ISBN 0415110475.

- ^ Faguet, Emile (1970). Politicians & Moralists of the Nineteenth Century. Freeport: Books for Libraries Press. pp. 147. ISBN 0836918282.

- ^ Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. The Philosophy of Misery: The Evolution of Capitalism. BiblioBazaar, LLC (2006). ISBN 1426409087 pp. 217

- ^ Goodway, David (2006). Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow. Liverpool University Press. p. 99.

- ^ Moggach, Douglas. The New Hegelians. Cambridge University Press. p. 177

- ^ Moggach, Douglas. The New Hegelians. Cambridge University Press, 2006 p. 190

- ^ Moggach, Douglas. The New Hegelians. Cambridge University Press, 2006 p. 183

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: A Library of Universal Knowledge. Encyclopedia Corporation. p. 176

- ^ Heider, Ulrike. Anarchism: Left, Right and Green, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1994, pp. 95-96

- ^ Moggach, Douglas. The New Hegelians. Cambridge University Press, 2006 p. 191

- ^ Stirner, Max. The Ego and Its Own, p. 248

- ^ Moggach, Douglas. The New Hegelians. Cambridge University Press, 2006 p. 194

- ^ Weir, David. Anarchy & Culture. University of Massachusetts Press. 1997. p. 146

- ^ McElroy, Wendy. Benjamin Tucker, Individualism, & Liberty: Not the Daughter but the Mother of Order. Literature of Liberty: A Review of Contemporary Liberal Thought (1978-1982). Institute for Human Studies. Autumn 1981, VOL. IV, NO. 3

- ^ a b Levy, Carl. "Anarchism". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007.

- ^ Avrich, Paul. "The Anarchists in the Russian Revolution". Russian Review, Vol. 26, No. 4. (Oct., 1967). p. 343

- ^ For Ourselves, [1] The Right to Be Greedy: Theses On The Practical Necessity Of Demanding Everything, 1974.

- ^ see, for example, Christopher Gray, Leaving the Twentieth Century, p. 88.

- ^ Emma Goldman, Anarchism and Other Essays, p. 50.

- ^ a b Avrich, Paul (2006). The Russian Anarchists. Stirling: AK Press. p. 56. ISBN 1904859488.

- ^ Madison, Charles A. (1945). "Anarchism in the United States". Journal of the History of Ideas 6 (1): 46–66. doi:.

- ^ Johnson, Ellwood. The Goodly Word: The Puritan Influence in America Literature, Clements Publishing, 2005, p. 138.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences, edited by Edwin Robert Anderson Seligman, Alvin Saunders Johnson, 1937, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Bottomore, Tom (1991). "Anarchism". A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Oxford: Blackwell Reference. pp. 21. ISBN 0631180826.

- ^ Brooks, Frank H. 1994. The Individualist Anarchists. Transaction Publishers. p.15

- ^ "Some portion, at least, of those who have attended the public meetings, know that EQUITABLE COMMERCE is founded on a principle exactly opposite to combination; this principle may be called that of Individuality. It leaves every one in undisturbed possession of his or her natural and proper sovereignty over its own person, time, property and responsibilities; & no one is acquired or expected to surrender any "portion" of his natural liberty by joining any society whatever; nor to become in any way responsible for the acts or sentiments of any one but himself; nor is there any arrangement by which even the whole body can exercise any government over the person, time property or responsibility of a single individual." - Josiah Warren, Manifesto

- ^ Butler, Ann Caldwell. Josiah Warren and the Sovereignty of the Individual. The Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. IV, No. 4 (Fall 1980)

- ^ McElroy, Wendy (2000-01-01). "American Anarchism". The Independent Institute. http://www.independent.org/issues/article.asp?id=10. Retrieved on 2008-07-12.

- ^ Josiah Warren, Equitable Commerce (1849), p. 10.

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin. State Socialism and Anarchism

- ^ The Individualist Anarchists, p. 276

- ^ Carl Watner. Benjamin Tucker and His Periodical, Liberty. Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. 1, No. 4, p. 308

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin. "Instead of a Book" (1893)

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin. Liberty October 19, 1891

- ^ Spooner, Lysander. No Treason

- ^ Spooner, Lysander. Natural Law

- ^ McElroy, Wendy. A Reconsideration of Trial by Jury, Forumulations, Winter 1998-1999, Free Nation Foundation

- ^ de Cleyre, Voltairine. Anarchism. Originally published in Free Society, 13 October 1901. Published in Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine de Cleyre, SUNY Press 2005, p. 224

- ^ Madison, Charles A. Anarchism in the United States. Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol 6, No 1, January 1945, p. 53. He cites The Science of Society, by Stephen Pearl Andrews, New York 1853, 149

- ^ Andrews, Stephen Pearl. The Science of Society. Nichols, 1854. p. 211

- ^ explained in The Science of Society by Stephen Pearl Andrews. Nichols, 1854. pp. 186-214

- ^ Review by Edward P. Stringham of The Debates if Liberty: An Overview of Individualist Anrachism, 1881-1908. The Independent Review. VOLUME IX, NUMBER 1, SUMMER 2004, p. 144 [2]

- ^ Spooner, Lysander. The Law of Intellectual Property: or an essay on the right of authors and inventors to a perpetual property in their ideas., Chaper 1, Section VI.

- ^ Tucker, Instead of a Book, p. 350

- ^ Brown, Susan Love, "The Free Market as Salvation from Government: The Anarcho-Capitalist View", Meanings of the Market: The Free Market in Western Culture, edited by James G. Carrier, Berg/Oxford, 1997, p. 107 and p. 104)

- ^ Schwartzman, Jack. Ingalls, Hanson, and Tucker: Nineteenth-Century American Anarchists. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 62, No. 5 (November, 2003). p. 325

- ^ McElroy, Wendy. 2000. American Anarchism. The Independent Institute.

- ^ a b Brown, Susan Love, The Free Market as Salvation from Government: The Anarcho-Capitalist View, Meanings of the Market: The Free Market in Western Culture, edited by James G. Carrier, Berg/Oxford, 1997, p. 103)

- ^ [Tucker, Liberty, no. 129]

- ^ Patterns of Anarchy, p. 272?

- ^ [Liberty, no. 172, p. 7]

- ^ Avrich, Paul. 2006. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America. AK Press. p. 6

- ^ McElroy, Wendy. The Debates of Liberty. Lexington Books, 2003, p. 11

- ^ Outhwaite, William. The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought, Anarchism entry, Blackwell Publishing, 2003, p. 13

- ^ a b Carson, Kevin (2007). "Preface". Studies in Mutualist Political Economy. BookSurge Publishing. ISBN 1419658697.

- ^ Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought, 1987, ISBN 0-631-17944-5, p. 290

- ^ Gordon, David. The Essential Rothbard. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2007. pp. 12-13.

- ^ "The Spooner-Tucker Doctrine: An Economist's View." A Way Out. May-June, 1965. Later republished in Egalitarianism As A Revolt Against Nature by Rothbard, 1974. Later published in Journal of Libertarian Studies, 2000. The Spooner-Tucker Doctrine: An Economist's View

- ^ Karl Hess in The Death of Politics, 1969.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray. The Spooner-Tucker Doctrine: An Economist's View The Spooner-Tucker Doctrine: An Economist's View

- ^ Rothbard, Murray (1969) Consfiscation and the Homestead Principle The Libertatian Forum Vol. I, No. VI (June 15, 1969) Retrieved 5 August 2006

- ^ Friedman, David. The Machinery of Freedom: Guide to a Radical Capitalism. Harper & Row. pp. 144-145 "Instead of corporation there are large groups of entrepreneurs related by trade, not authority. Each sells, not his time, but what his time produces."

- ^

- Alan and Trombley, Stephen (Eds.) Bullock, The Norton Dictionary of Modern Thought, W. W. Norton & Company (1999), p. 30

- Barry, Norman. Modern Political Theory, 2000, Palgrave, p. 70

- Adams, Ian. Political Ideology Today, Manchester University Press (2002) ISBN 0-7190-6020-6, p. 135

- Grant, Moyra. Key Ideas in Politics, Nelson Thomas 2003 ISBN 0-7487-7096-8, p. 91

- Heider, Ulrike. Anarchism: Left, Right, and Green, City Lights, 1994. p. 3.

- Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America, Abridged Paperback Edition (1996), p. 282

- Tormey, Simon. Anti-Capitalism, One World, 2004. pp. 118-119

- Raico, Ralph. Authentic German Liberalism of the 19th Century, Ecole Polytechnique, Centre de Recherce en Epistemologie Appliquee, Unité associée au CNRS, 2004.

- Busky, Donald. Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey, Praeger/Greenwood (2000), p. 4

- Heywood, Andrew. Politics: Second Edition, Palgrave (2002), p. 61

- Offer, John. Herbert Spencer: Critical Assessments, Routledge (UK) (2000), p. 243

- ^ Jainendra, Jha. 2002. "Anarchism". Encyclopedia of Teaching of Civics and Political Science. p. 52. Anmol Publications.

- ^

- K, David. "What is Anarchism?" BASTARD Press (2005)

- Marshall, Peter. Demanding the Impossible, London: Fontana Press, 1992 (ISBN 0 00 686245 4) Chapter 38

- MacSaorsa, Iain. "Is "anarcho" capitalism against the state?" SPUNK Press (archive)

- Wells, Sam. "Anarcho-Capitalism is Not Anarchism, and Political Competition is Not Economic Competition" Frontlines 1 (January 1979)

- ^

- Peikoff, Leonard. 'Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand' Dutton Adult (1991) Chapter "Government"

- Doyle, Kevin. 'Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias' New York: Lexington Books, (2002) p.447-8

- Sheehan, Seán M. 'Anarchism' Reaktion Books, 2003 p. 17

- Kelsen, Hans. The Communist Theory of Law. Wm. S. Hein Publishing (1988) p. 110

- Egbert. Tellegen, Maarten. Wolsink 'Society and Its Environment: an introduction' Routledge (1998) p. 64

- Jones, James 'The Merry Month of May' Akashic Books (2004) p. 37-38

- Sparks, Chris. Isaacs, Stuart 'Political Theorists in Context' Routledge (2004) p. 238

- Bookchin, Murray. 'Post-Scarcity Anarchism' AK Press (2004) p. 37

- Berkman, Alexander. 'Life of an Anarchist' Seven Stories Press (2005) p. 268

- ^ Konkin III, Samuel Edward. "Smashing the State for Fun and Profit Since 1969". Spaz.org. http://www.spaz.org/~dan/individualist-anarchist/software/konkin-interview.html. Retrieved on 2008-10-14.

- ^ Agorism is revolutionary market anarchism. Agorism.info

- ^ Bookchin, Murray (1995). Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism. Stirling: AK Press. ISBN 9781873176832.

- ^ Bookchin, Murray. "Communalism: The Democratic Dimensions of Social Anarchism". Anarchism, Marxism and the Future of the Left: Interviews and Essays, 1993-1998. AK Press, 1999, p. 155

- ^ Meltzer, Albert. Anarchism: Arguments For and Against. AK Press, 2000. pp. 114-115

- ^ Meltzer, Albert. Anarchism: Arguments For and Against. AK Press, 2000. p 50

- ^ Griffith, Gareth. Socialism and Superior Brain: The Political Thought of George Bernard Shaw. Routledge (UK). 1993. p. 310

- ^ Anderson, Carlotta R. All-American Anarchist: Joseph A. Labadie and the Labor Movement, Wayne State University Press, 1998, p. 250

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin. Economic Rent.

- ^ Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 14.

- ^ Carson, Kevin, "A Mutualist FAQ".

- ^ Freeden, Micheal. Ideologies and Political Theory: A Conceptual Approach. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019829414X. pp. 313-314

- ^ Long, Roderick. T. An Interview With Roderick Long

- ^ Morris, Christopher. 1992. An Essay on the Modern State. Cambridge University Press. p. 61. (Used synonymously with "individualist anarchism" when referring to individualist anarchism that supports a market society)

- ^ "One is anarcho-capitalism, a form of libertarian anarchism which demands that the state should be abolished and that private individuals and firms should control social and economic affairs" (Barbara Goodwin, "Using Political Ideas", fourth edition, John Wiley & Sons (1987), p. 137-138)

- ^ "the 'libertarian anarchist' could on the face of it either be in favour of capitalism or against it...Pro-capitalist anarchism, is as one might expect, particularly prevalent in the U.S. where it feeds on the strong individualist and libertarian currents that have always been part of the American political imaginary. To return to the point, however, there are individualist anarchists who are most certainly not anti-capitalist and there are those who may well be." Tormey, Simon, Anti-Capitalism, A Beginner's Guide, Oneworld Publications, 2004, p. 118-119

- ^ .Friedman presents practical and economic arguments for both libertarianism in general and libertarian anarchism, which he calls anarcho-capitalism." Burton, Daniel C. Libertarian Anarchism: Why It Is Best For Freedom, Law, The Economy And The Environment, And Why Direct Action Is The Way To Get It, Political Notes No. 168, Libertarian Alliance (2001), ISSN 0267-7058 ISBN 1 85637 504 8, p. 1 & 7 - Note: Burton is the founder of the Individualist Anarchist Society at the University of California at Berkeley.

- ^ a b Machan, T.R. (2006). Libertarianism Defended. Ashgate Publishing. p. 257.

- ^ Carey, G.W. (1984). Freedom and Virtue: The Conservative/libertarian Debate. University Press of America.

- ^ Harcourt, GC. The Capitalist Alternative: An Introduction to Neo-Austrian Economics. JSTOR.

[edit] External links

- Individualist anarchism at Government and Politics Research Guide

- Individualist-Anarchist.Net

- The Alliance of the Libertarian Left

- "An Introduction to Individualist Anarchism" by Andrew Rogers

- Articles by Wendy McElroy about Individualist Anarchism

- Essay by Benjamin Tucker in 1886