Nicaragua

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Republic of Nicaragua

República de Nicaragua

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: En Dios Confiamos (Spanish) "In God We Trust"[1] |

||||||

| Anthem: Salve a ti, Nicaragua (Spanish) Hail to thee, Nicaragua |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Managua |

|||||

| Official languages | Spanish1 | |||||

| Recognised regional languages | Miskito Coastal Creole | |||||

| Ethnic groups | 69% Mestizo 17% white 9% black 5% Amerindian |

|||||

| Demonym | Nicaraguan | |||||

| Government | Presidential republic | |||||

| - | President | Daniel Ortega (FSLN) | ||||

| - | Vice President | Jaime Morales Carazo | ||||

| Independence | from Spain | |||||

| - | Declared | 15 September 1821 | ||||

| - | Recognized | 25 July 1850 | ||||

| - | Revolution | 19 July 1979 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 129,494 km2 (97th) 50,193 sq mi |

||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | July 2006 estimate | 5,603,000 (107th) | ||||

| - | 2005 census | 5,142,098 | ||||

| - | Density | 42/km2 (132nd) 109/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $15.912 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $2,628[2] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2007 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $5.724 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $945[2] | ||||

| Gini (2001) | 43.1 (medium) | |||||

| HDI (2008) | ▲ 0.699 (medium) (120th) | |||||

| Currency | Córdoba (NIO) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC-6) | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Internet TLD | .ni | |||||

| Calling code | 505 | |||||

| 1 | English and indigenous languages on Caribbean coast are also spoken. | |||||

Nicaragua (IPA: /ˌnɪkəˈrɑːɡwə/) officially the Republic of Nicaragua (Spanish: República de Nicaragua, Spanish pronunciation: [reˈpuβlika ðe nikaˈɾaɣwa]), is a representative democratic republic. It is the largest state in Central America with an area of 130,000 km2, about the size of England. The country is bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The Pacific Ocean lies to the west of the country, the Caribbean Sea to the east. Falling within the tropics, Nicaragua sits 11 degrees north of the Equator, in the Northern Hemisphere. Nicaragua's capital city is Managua.

The origin of the name 'Nicaragua' is unclear; one theory is that it was coined by Spanish colonists based upon the name of the local chief at that time, Nicarao; another is that it may have meant 'surrounded by water' in an indigenous language (this could either be a reference to its two large freshwater lakes, Lake Nicaragua and Lake Managua, or to the fact that it bounded on the east and the west by oceans).

Contents |

[edit] History

[edit] Pre-Columbian history

In Pre-Columbian times the Indigenous people in what is now known as Nicaragua, were part of the Intermediate Area located between the Mesoamerican and Andean cultural regions and within the influence of the Isthmo-Colombian area. It was the point where the Mesoamerican and South American native cultures met.

This is confirmed by the ancient footprints of Acahualinca, along with other archaeological evidence, mainly in the form of ceramics and statues made of volcanic stone like the ones found on the island of Zapatera and petroglyphs found on Ometepe island. At the end of the 15th century, western Nicaragua was inhabited by several indigenous peoples related by culture and language to the Mayans.[3] They were primarily farmers who lived in towns, organized into small kingdoms. Meanwhile, the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua was inhabited by other peoples, mostly chibcha related groups, that had migrated from what is now Colombia. They lived a less sedentary life based on hunting and gathering.[4] The people of eastern Nicaragua appear to have traded with, and been influenced by, the native peoples of the Caribbean, as round thatched huts and canoes, both typical of the Caribbean, were common in eastern Nicaragua. In the west and highland areas, occupying the territory between Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific Coast, the Niquirano were governed by chief Nicarao, or Nicaragua, a rich ruler who lived in Nicaraocali, now the city of Rivas. The Chorotega lived in the central region of Nicaragua. These two groups had intimate contact with the Spanish conquerors, paving the way for the racial mix of native and European stock now known as mestizos.[3] However, within three decades an estimated Indian population of one million plummeted, as approximately half of the indigenous people in western Nicaragua died from the rapid spread of new diseases brought by the Spaniards, something the indigenous people of the Caribbean coast managed to escape due to the remoteness of the area.[3]

[edit] The Spanish conquest

In 1502, Christopher Columbus was the first European known to have reached what is now Nicaragua as he sailed south along the Central America isthmus. On his fourth voyage Columbus sailed alongside and explored the Mosquito Coast on the east of Nicaragua.[5] The first attempt to conquer what is now known as Nicaragua was by Gil González Dávila,[6] whose Central American exploits began with his arrival in Panama in January 1520. González claimed to have converted some 30,000 indigenous peoples and discovered a possible transisthmian water link. After exploring and gathering gold in the fertile western valleys González was attacked by the indigenous people, some of whom were commanded by Nicarao and an estimated 3,000 led by chief Diriangén.[7] González later returned to Panama where governor Pedrarias Dávila attempted to arrest him and confiscate his treasure, some 90,000 pesos of gold. This resulted in González fleeing to Santo Domingo.

It was not until 1524 that the first Spanish permanent settlements were founded.[6] Conquistador Francisco Hernández de Córdoba founded two of Nicaragua's principal towns in 1524: Granada on Lake Nicaragua was the first settlement and León east of Lake Managua came after. Córdoba soon found it necessary to prepare defenses for the cities and go on the offensive against incursions by the other conquistadores. Córdoba was later publicly beheaded following a power struggle with Pedrarias Dávila, his tomb and remains were discovered some 500 years later in the Ruins of León Viejo.[8]

The inevitable clash between the Spanish forces did not impede their devastation of the indigenous population. The Indian civilization was destroyed. The series of battles came to be known as The War of the Captains.[9] By 1529, the conquest of Nicaragua was complete. Several conquistadores came out winners, and some were executed or murdered. Pedrarias Dávila was a winner; although he had lost control of Panama, he had moved to Nicaragua and established his base in León. Through adroit diplomatic machinations, he became the first governor of the colony.[8] The land was parceled out to the conquistadores. The area of most interest was the western portion. Many indigenous people were soon enslaved to develop and maintain "estates" there. Others were put to work in mines in northern Nicaragua, few were killed in warfare, and the great majority were sent as slaves to other New World Spanish colonies, for significant profit to the new landed aristocracy. Many of the indigenous people died as a result of disease and neglect by the Spaniards who controlled everything necessary for their subsistence.[6]

[edit] From colony to nation

In 1538, the Viceroyalty of New Spain was established. By 1570, the southern part of New Spain was designated the Captaincy General of Guatemala. The area of Nicaragua was divided into administrative "parties" with León as the capital. In 1610, the Momotombo volcano erupted, destroying the capital. It was rebuilt northwest of what is now known as the Ruins of Old León. Nicaragua became a part of the Mexican Empire and then gained its independence as a part of the United Provinces of Central America in 1821 and as an independent republic in its own right in 1838. The Mosquito Coast based on the Caribbean coast was claimed by the United Kingdom and its predecessors as a protectorate from 1655 to 1850; this was delegated to Honduras in 1859 and transferred to Nicaragua in 1860, though it remained autonomous until 1894. Jose Santos Zelaya, president of Nicaragua from 1893-1909, managed to negotiate for the annexation of this region to the rest of Nicaragua. In his honour the entire region was named Zelaya.

Much of Nicaragua's independence was characterized by rivalry between the liberal elite of León and the conservative elite of Granada. The rivalry often degenerated into civil war, particularly during the 1840s and 1850s. Initially invited by the Liberals in 1855 to join their struggle against the Conservatives, a United States adventurer named William Walker (later executed in Honduras) set himself up as president of Nicaragua, after conducting a farcical election in 1856. Honduras and other Central American countries united to drive him out of Nicaragua in 1857, after which a period of three decades of Conservative rule ensued.[10]

In the 1800s Nicaragua experienced a wave of immigration, primarily from Europe. In particular, families from Germany, Italy, Spain, France and Belgium moved to Nicaragua to set up businesses with money they brought from Europe. They established many agricultural businesses such as coffee and sugar cane plantations, and also newspapers, hotels and banks.

Throughout the late nineteenth century the United States (and several other European powers) considered a scheme to build a canal across Nicaragua linking the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic. A bill was put before the U.S. Congress in 1899 to build the canal, but it was not passed, and instead the construction of the Panama Canal began.

[edit] United States involvement (1909 - 1933)

In 1909, the United States provided political support to conservative-led forces rebelling against President Zelaya. U.S. motives included differences over the proposed Nicaragua Canal, Nicaragua's potential as a destabilizing influence in the region, and Zelaya's attempts to regulate foreign access to Nicaraguan natural resources. On November 18, 1909, U.S. warships were sent to the area after 500 revolutionaries (including two Americans) were executed by order of Zelaya. The U.S. justified the intervention by claiming to protect U.S. lives and property. Zelaya resigned later that year.

In August 1912 the President of Nicaragua, Adolfo Díaz, requested that the Secretary of War, General Luis Mena, resign for fear that he was leading an insurrection. Mena fled Managua with his brother, the Chief of Police of Managua, to start an insurrection. When the U.S. Legation asked President Díaz to ensure the safety of American citizens and property during the insurrection he replied that he could not and that...

| “ | In consequence my Government desires that the Government of the United States guarantee with its forces security for the property of American Citizens in Nicaragua and that it extend its protection to all the inhabitants of the Republic.[11] | ” |

U.S. Marines occupied Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933,[12] except for a nine month period beginning in 1925. From 1910 to 1926, the conservative party ruled Nicaragua. The Chamorro family, which had long dominated the party, effectively controlled the government during that period. In 1914, the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty was signed, giving the U.S. control over the proposed canal, as well as leases for potential canal defenses.[13] Following the evacuation of U.S. marines, another violent conflict between liberals and conservatives took place in 1926, known as the Constitutionalist War, which resulted in a coalition government and the return of U.S. Marines.[14]

From 1927 until 1933, Gen. Augusto C. Sandino led a sustained guerrilla war first against the Conservative regime and subsequently against the U.S. Marines, who withdrew upon the establishment of a new Liberal government. Sandino was the only Nicaraguan general to refuse to sign the el tratado del Espino Negro agreement and then headed up to the northern mountains of Las Segovias, where he fought the US Marines for over five years.[15] The revolt finally forced the United States to compromise and leave the country. When the Americans left in 1933, they set up the Guardia Nacional (National Guard),[16] a combined military and police force trained and equipped by the Americans and designed to be loyal to U.S. interests. Anastasio Somoza García, a close friend of the American government, was put in charge. He was one of the three rulers of the country, the others being Sandino and the President Juan Bautista Sacasa.

After the US Marines withdrew from Nicaragua in January 1933, Sandino and the newly-elected Sacasa government reached an agreement by which he would cease his guerrilla activities in return for amnesty, a grant of land for an agricultural colony, and retention of an armed band of 100 men for a year.[17] But a growing hostility between Sandino and Somoza led Somoza to order the assassination of Sandino.[16][18][19] Fearing future armed opposition from Sandino, Somoza invited him to a meeting in Managua, where Sandino was assassinated on February 21 of 1934 by the National Guard. Hundreds of men, women, and children were executed later.[20]

[edit] The Somoza Dynasty (1936 - 1979)

Nicaragua has experienced several military dictatorships, the longest one being the rule of the Somoza family for much of the 20th century. The Somoza family came to power as part of a US-engineered pact in 1927 that stipulated the formation of the National Guard to replace the small individual armies that had long reigned in the country.[21] Somoza deposed Sacasa and became president on January 1, 1937 in a rigged election.[16]

Nicaragua declared war[when?] on Germany during World War II. No troops were sent to the war but Somoza did seize the occasion to confiscate attractive properties held by German-Nicaraguans, the best-known of which was the Montelimar estate which today operates as a privately-owned luxury resort and casino[22]. In 1945 Nicaragua was the first country to ratify the UN Charter,[23].

Somoza used the National Guard to force Sacasa to resign, and took control of the country in 1937, destroying any potential armed resistance.[24] Somoza was in turn assassinated by Rigoberto López Pérez, a liberal Nicaraguan poet, in 1956. After his father's death, Luis Somoza Debayle, the eldest son of the late dictator, was appointed President by the congress and officially took charge of the country.[16] He is remembered by some for being moderate, but was in power only for a few years and then died of a heart attack. Then came president Rene Schick whom most Nicaraguans viewed "as nothing more than a puppet of the Somozas".[25] Somoza's brother, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, a West Point graduate, succeeded his father in charge of the National Guard, controlled the country, and officially took the presidency after Schick.

Nicaragua experienced economic growth during the 1960s and 1970s largely as a result of industrialization,[26] and became one of Central America's most developed nations despite its political instability. Due to its stable and high growth economy, foreign investments grew, primarily from U.S. companies such as Citigroup, Sears, Westinghouse and Coca Cola. However, the capital city of Managua suffered a major earthquake in 1972 which destroyed nearly 90% of the city creating major losses.[27] Some Nicaraguan historians see the 1972 earthquake that devastated Managua as the final 'nail in the coffin' for Somoza. The mishandling of relief money also prompted Pittsburgh Pirates star Roberto Clemente to personally fly to Managua on 31 December 1972, but he died enroute in an airplane accident.[28] Even the economic elite were reluctant to support Somoza, as he had acquired monopolies in industries that were key to rebuilding the nation,[29] and did not allow the elite to share the profits that would result. In 1973 (the year of reconstruction) many new buildings were built, but the level of corruption in the government prevented further growth, and the ever increasing tensions and anti-government uprisings slowed growth in the last two years of the Somoza dynasty.

[edit] Nicaraguan Revolution

In 1961 Carlos Fonseca, turned back to the historical figure of Sandino, and along with 2 others founded the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN).[16] The FSLN was a tiny party throughout most of the 1960s, but Somoza's utter hatred of it and his heavy-handed treatment of anyone he suspected to be a Sandinista sympathizer gave many ordinary Nicaraguans the idea that the Sandinistas were much stronger.

After the 1972 earthquake and Somoza's brazen corruption, mishandling of relief, and refusal to rebuild Managua, the ranks of the Sandinistas were flooded with young disaffected Nicaraguans who no longer had anything to lose.[30] These economic problems propelled the Sandinistas in their struggle against Somoza by leading many middle- and upper-class Nicaraguans to see the Sandinistas as the only hope for removing the brutal Somoza regime. On January 10, 1978, Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, the editor of the national newspaper La Prensa and ardent opponent of Somoza, was assassinated.[31] This is believed to have led to the extreme general disappointment with Somoza. The planners and perpetrators of the murder were at the highest echelons of the Somoza regime and included the dictator's son, “El Chiguin”, the President of Housing, Cornelio Hueck, the Attorney General, and Pedro Ramos, a close Cuban ally who commercialized blood plasma.[31]

The Sandinistas, supported by some of the populace, elements of the Catholic Church, and regional and international governments, took power in July 1979. Somoza fled the country and eventually ended up in Paraguay, where he was assassinated in September 1980, allegedly by members of the Argentinian Revolutionary Workers Party.[32] To begin the task of establishing a new government, they created a Council (or junta) of National Reconstruction, made up of five members – Sandinista militants Daniel Ortega and Moises Hassan, novelist Sergio Ramírez Mercado (a member of Los Doce "the Twelve"), businessman Alfonso Robelo Callejas, and Violeta Barrios de Chamorro (the widow of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro). The latter two later resigned from the junta refusing to take part in the marxist-leninist policies of the Sandinista Movement, this gave Violeta Barrios de Chamorro a growing level of support by a large percentage of the Nicaraguan population who also opposed the communist regime. The preponderance of power, however, remained with the Sandinistas and their mass organizations, including the Sandinista Workers' Federation (Central Sandinista de Trabajadores), the Luisa Amanda Espinoza Nicaraguan Women's Association (Asociación de Mujeres Nicaragüenses Luisa Amanda Espinoza), and the National Union of Farmers and Ranchers (Unión Nacional de Agricultores y Ganaderos).

On the Atlantic Coast a small uprising also occurred in support of the Sandinistas. This event is often overlooked in histories about the Sandinista revolution. A group of Creoles led by a native of Bluefields, Dexter Hooker (aka Commander Abel), raided a Somoza-owned business to gain access to food, guns and money before heading off to join Sandinista fighters who had liberated the city of El Rama. The 'Black Sandinistas' returned to Bluefields on July 19, 1979 and took the city without a fight. However, the Black Sandinistas were challenged by a group of mestizo Sandinista fighters. The ensuing standoff between the two groups, with the Black Sandinistas occupying the National Guard barracks (the cuartel) and the mestizo group occupying the Town Hall (Palacio) gave the revolution on the Atlantic Coast a racial dimension which was absent from other parts of the country. The Black Sandinistas were assisted in their power struggle with the Palacio group by the arrival of the Simon Bolivar International Brigade from Costa Rica. One of the brigade's members, an African-Costa Rican called Marvin Wright (aka Kalalu) became known for the rousing speeches he would make, which included elements of black power ideology in his attempts to unite all the black militias that had formed in Bluefields. The introduction of a racial element into the revolution was not welcomed by the Sandinista National Directorate which expelled Kalalu and the rest of the brigade from Nicaragua and sent them to Panama.[33]

[edit] Sandinistas and the Contras

Upon assuming office in 1981, U.S. President Ronald Reagan condemned the FSLN for joining with Cuba in supporting Marxist revolutionary movements in other Latin American countries such as El Salvador. His administration authorized the CIA to have their paramilitary officers from their elite Special Activities Division begin financing, arming and training rebels, some of whom were the remnants of Somoza's National Guard, as anti-Sandinista guerrillas that were branded "counter-revolutionary" by leftists (contrarrevolucionarios in Spanish).[34] This was shortened to Contras, a label the anti-Communist forces chose to embrace. Eden Pastora and many of the indigenous guerrilla forces, who were not associated with the "Somozistas," also resisted the Sandinistas. The Contras operated out of camps in the neighboring countries of Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south.[34] As was typical in guerrilla warfare, they were engaged in a campaign of economic sabotage in an attempt to combat the Sandinista government and disrupted shipping by planting underwater mines in Nicaragua's Corinto harbour,[35] an action condemned by the World Court as illegal.[36][37] The U.S. also sought to place economic pressure on the Sandinistas, and the Reagan administration imposed a full trade embargo.[38]

U.S. support for this Nicaraguan insurgency continued in spite of the fact that impartial observers from international groupings such as the European Economic Community, religious groups sent to monitor the election, and observers from democratic nations such as Canada and the Republic of Ireland concluded that the Nicaraguan general elections of 1984 were completely free and fair. The Reagan administration disputed these results however, despite the fact that the government of the United States never had any observers in Nicaragua at the time. The elections were not also recognized as legitimate because the Nicaraguan Democratic Coordinator, considered the main opposition group, and the only group of democratic opposition in the country did not participated in the elections. The Nicaraguan Democratic Coordinator did not participated in the elections duet to the government's lack of response to its document "a step toward democracy, free elections" issue in 1982. The document was asking the government to re-establish all civil rights: freedom of speech, freedom of organization, release of all political prisoners, cease of hostilities against the opposition, lifting the censorship on the media and abolishing all the laws violating humans rights. [39][40]

After the U.S. Congress prohibited federal funding of the Contras in 1983, the Reagan administration continued to back the Contras by covertly selling arms to Iran and channeling the proceeds to the Contras (the Iran-Contra Affair).[41] When this scheme was revealed, Reagan admitted that he knew about the Iranian "arms for hostages" dealings but professed ignorance about the proceeds funding the Contras; for this, National Security Council aide Lt. Col. Oliver North took much of the blame. Senator John Kerry's 1988 U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations report on Contra-drug links concluded that "senior U.S. policy makers were not immune to the idea that drug money was a perfect solution to the Contras' funding problems."[42] According to the National Security Archive, Oliver North had been in contact with Manuel Noriega, a Panamanian general and the de facto military dictator of Panama from 1983 to 1989 when he was overthrown and captured by a U.S. invading force.[43] He was taken to the United States, tried for drug trafficking, and imprisoned in 1992.[44]

In August 1996, San Jose Mercury News reporter Gary Webb published a series titled Dark Alliance, linking the origins of crack cocaine in California to the Contras.[45] Freedom of Information Act inquiries by the National Security Archive and other investigators unearthed a number of documents showing that White House officials, including Oliver North, knew about and supported using money raised via drug trafficking to fund the Contras. Sen. John Kerry's report in 1988 led to the same conclusions; however, major media outlets, the Justice Department, and Reagan denied the allegations.[46]

The International Court of Justice, in regard to the case of Nicaragua v. United States of America in 1984, found; "the United States of America was under an obligation to make reparation to the Republic of Nicaragua for all injury caused to Nicaragua by certain breaches of obligations under customary international law and treaty-law committed by the United States of America".[47] But was rejected citing the 'Connally Amendment', which excludes from the International court of Justice's jurisdiction "disputes with regard to matters that are essentially within the jurisdiction of the United States of America, determined by the United States of America"[48]

[edit] 1990s and the post-Sandinista era

Multi-party democratic elections were held in 1990, which saw the defeat of the Sandinistas by a coalition of anti-Sandinista (from the left and right of the political spectrum) parties led by Violeta Chamorro, the widow of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro. The defeat shocked the Sandinistas as numerous pre-election polls had indicated a sure Sandinista victory and their pre-election rallies had attracted crowds of several hundred thousand people.[49] The unexpected result was subject to a great deal of analysis and comment, and was attributed by commentators such as Noam Chomsky and S. Brian Willson to the U.S./Contra threats to continue the war if the Sandinistas retained power, the general war-weariness of the Nicaraguan population, and the abysmal Nicaraguan economic situation.

P. J. O'Rourke countered the US centered criticism in "Return of the Death of Communism", "the unfair advantages of using state resources for party ends, about how Sandinista control of the transit system prevented UNO supporters from attending rallies, how Sandinista domination of the army forced soldiers to vote for Ortega and how Sandinista bureaucracy kept $3.3 million of U.S. campaign aid from getting to UNO while Daniel Ortega spent millions donated by overseas people and millions and millions more from the Nicaraguan treasury ..."[50]

Exit polls of Nicaraguans reported Chamorro's victory over Ortega was achieved with only 55%.[51] Violeta Chamorro was the first woman to be popularly elected as President of a Latin American nation and first woman president of Nicaragua. Exit polling convinced Daniel Ortega that the election results were legitimate, and were instrumental in his decision to accept the vote of the people and step down rather than void the election. Nonetheless Ortega vowed that he would govern "desde abajo" (from below),[52] in other words due to his widespread control of institutions and Sandinista individuals in all government agencies, he would still be able to maintain control and govern even without being president.

Chamorro received an economy entirely in ruins. The per capita income of Nicaragua had been reduced by over 80% during the 1980s, and a huge government debt which ascended to US$12 billion primarily due to financial and social costs of the Contra war with the Sandinista-led government.[53] Much to the surprise of the U.S. and the contra forces, Chamorro did not dismantle the Sandinista People's Army, though the name was changed to the Nicaraguan Army. Chamorro's main contribution to Nicaragua was the disarmament of groups in the northern and central areas of the country. This provided stability that the country had lacked for over ten years.

In subsequent elections in 1996 Daniel Ortega and the Sandinistas of the FSLN were again defeated, this time by Arnoldo Alemán of the Constitutional Liberal Party (PLC).

In the 2001 elections the PLC again defeated the FSLN, with Enrique Bolaños winning the Presidency. However, President Bolaños subsequently brought forward allegations of money laundering, theft and corruption against former President Alemán. The ex-president was sentenced to 20 years in prison for embezzlement, money laundering, and corruption.[54] The Liberal members who were loyal to Alemán and also members of congress reacted angrily, and along with Sandinista parliament members stripped the presidential powers of President Bolaños and his ministers, calling for his resignation and threatening impeachment.

The Sandinistas alleged that their support for Bolaños was lost when U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell told Bolaños to keep his distance from the FSLN.[55] This "slow motion coup" was averted partially due to pressure from the Central American presidents who would fail to recognize any movement that removed Bolaños; the U.S., the OAS, and the European Union also opposed the "slow motion coup".[56] The proposed constitutional changes that were going to be introduced in 2005 against the Bolaños administration were delayed until January 2007 after the entrance of the new government. Though one day before they were to be enforced, the National Assembly postponed their enforcement until January 2008.

Before the general elections on 5 November 2006, the National Assembly passed a bill further restricting abortion in Nicaragua 52-0 (9 abstaining, 29 absent). President Enrique Bolaños supported this measure, and signed the bill into law on 17 November 2006,[57] as a result Nicaragua is one of three countries in the world where abortion is illegal with no exceptions, along with El Salvador and Chile.

Legislative and presidential elections took place on November 5, 2006. Daniel Ortega returned to the presidency with 37.99% of the vote. This percentage was enough to win the presidency outright, due to a change in electoral law which lowered the percentage requiring a runoff election from 45% to 35% (with a 5% margin of victory).[58]

[edit] Politics

Politics of Nicaragua takes place in a framework of a presidential representative democratic republic, whereby the President of Nicaragua is both head of state and head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the National Assembly. The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

Currently, Nicaragua's major political parties have been discussing the possibility of going from a presidential system to a parliamentary system. This way, there would be a clear differentiation between the head of government (Prime Minister) and the head of state (President).

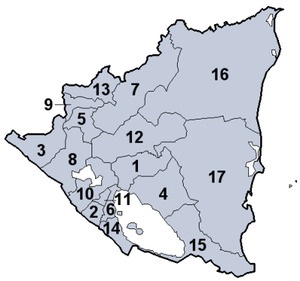

[edit] Departments and municipalities

Nicaragua is a unitary republic. For administrative purposes it is divided into 15 departments (departamentos) and two self-governing regions (autonomous communities) based on the Spanish model. The departments are then subdivided into 153 municipios (municipalities). The two autonomous regions are 'Región Autónoma Atlántico Norte' and 'Región Autónoma Atlántico Sur', often referred to as RAAN and RAAS, respectively; until they were granted autonomy in 1985 they formed the single department of Zelaya.[59]

|

[edit] Geography

Nicaragua occupies a landmass of 129,494 km² - roughly the size of Greece or the state of New York and 1.5 times larger than Portugal. Close to 20% of the country's territory is designated as protected areas such as national parks, nature reserves and biological reserves. The country is bordered by Costa Rica on the south and Honduras on the north, with the Caribbean Sea to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west.

Nicaragua has three distinct geographical regions: the Pacific Lowlands, the North-Central Highlands or highlands and the Atlantic Lowlands.

[edit] Pacific lowlands

Located in the west of the country, these lowlands consist of a broad, hot, fertile plain. Punctuating this plain are several large volcanoes of the Marrabios mountain range, including Mombacho just outside Granada, and Momotombo near León. The lowland area runs from the Gulf of Fonseca to Nicaragua's Pacific border with Costa Rica south of Lake Nicaragua. Lake Nicaragua is the largest freshwater lake in Central America (20th largest in the world),[60] and is home to the world's only freshwater sharks (Nicaraguan shark).[61] The Pacific lowlands region is the most populous, with over half of the nation's population. The capital city of Managua is the most populous and it is the only city with over 1.5 million inhabitants.

In addition to its beach and resort communities, the Pacific Lowlands is also the repository for much of Nicaragua's Spanish colonial heritage. Cities such as León and Granada abound in colonial architecture and artifacts; Granada, founded in 1524, is the oldest colonial city in the Americas.[62]

[edit] North-Central Highlands

This is an upland region away from the Pacific coast, with a cooler climate than the Pacific Lowlands. About a quarter of the country's agriculture takes place in this region, with coffee grown on the higher slopes. Oaks, pines, moss, ferns and orchids are abundant in the cloud forests of the region.

Bird life in the forests of the central region includes Resplendent Quetzal, goldfinches, hummingbirds, jays and toucanets.

[edit] Atlantic lowlands

This large rainforest region, irrigated by several large rivers and very sparsely populated. The Rio Coco is the largest river in Central America, it forms the border with Honduras. The Caribbean coastline is much more sinuous than its generally straight Pacific counterpart; lagoons and deltas make it very irregular.

Nicaragua's Bosawas Biosphere Reserve is located in the Atlantic lowlands, it protects 1.8 million acres (7,300 km²) of Mosquitia forest - almost seven percent of the country's area - making it the largest rainforest north of the Amazon in Brazil.[63]

Nicaragua's tropical east coast is very different from the rest of the country. The climate is predominantly tropical, with high temperature and high humidity. Around the area's principal city of Bluefields, English is widely spoken along with the official Spanish. The population more closely resembles that found in many typical Caribbean ports than the rest of Nicaragua.

A great variety of birds can be observed including eagles, turkeys, toucans, parakeets and macaws. Animal life in the area includes different species of monkeys, ant-eaters, white-tailed deer and tapirs.

[edit] Wildlife and Biodiversity

Rainforest in Nicaragua covers more than 2,000,000 ha, particularly on the Atlantic lowlands. As well as the Bosawas Biosphere Reserve (in the north) there is the Indio Maiz Biological Reserve (in the south), which protects 2,500 km² of the Atlantic Rainforest.

These two areas are very rich in biodiversity. There are 5 species of felines, including jaguar and cougar; 3 species of primates, spider monkey, howler monkey and capuchin monkey; 1 species of tapir, called Danto by the Nicaraguans; 3 species of anteaters and many more.

[edit] Economy

[edit] Exports

Nicaragua is primarily an agricultural country; agriculture constitutes 60% of its total exports which annually yield approximately US $300 million.[64] In addition, Nicaragua's Flor de Caña rum is renowned as among the best in Latin America, and its tobacco and beef are also well regarded. Nicaragua's agrarian economy has historically been based on the export of cash crops such as bananas, coffee, sugar, beef and tobacco. Light industry (maquila), tourism, banking, mining, fisheries, and general commerce are expanding. Nicaragua also depends heavily on remittances from Nicaraguans living abroad, which totaled $655.5 million in 2006.

[edit] Components of the economy

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2008 was estimated at $17.37 billion USD.[65] The service sector is the largest component of GDP at 56.9%, followed by the industrial sector at 26.1% (2006 est.). Agriculture represents only 17% of GDP (2008 est.). Nicaraguan labor force is estimated at 2.322 million of which 29% is occupied in agriculture, 19% in the industry sector and 52% in the service sector (est. 2008).

[edit] Poverty

Nicaragua is the second poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, measured in GDP per capita.[66][67] According to the CIA Fact Book, inflation averaged 8.1% from 2000 through 2006. As of 2007, Nicaragua's inflation stands at 9.8%. The World Bank also indicates moderate economic growth at an average of 5% from 1995 through 2004. In 2005 the economy grew 4%, with overall GDP reaching $4.91 billion. In 2006, the economy expanded by 3.7% as GDP reached $5.3 billion. As of 2008, it stands at $6.5 billion.

According to the PNUD, 48% of the population in Nicaragua live below the poverty line[68], 79.9% of the population live with less than $2 per day[69], unemployment is 3.9%, and another 46.5% are underemployed (2008 est.). As in many other developing countries, a large segment of the economically poor in Nicaragua are women. In addition, a relatively high proportion of Nicaragua's homes have a woman as head of household: 39% of urban homes and 28% of rural homes. According to UN figures, 80% of the indigenous people (who make up 5% of the population) live on less than $1 per day.[70]

[edit] Infrastructure

During the war between the US-backed Contras and the elected government of the Sandinistas in the 1980s, much of the country's infrastructure was damaged or destroyed.[71] Inflation averaged 30% throughout the 1980s. After the United States imposed a trade embargo in 1985, which lasted 5 years, Nicaragua's inflation rate rose dramatically. The 1985 annual rate of 220% tripled the following year and rose to more than 13,000% in 1988, the highest rate for any country in the Western Hemisphere in that year.

The country is still a recovering economy and it continues to implement further reforms, on which aid from the IMF is conditional. In 2005 finance ministers of the leading eight industrialized nations (G8) agreed to forgive some of Nicaragua's foreign debt, as part of the HIPC program. According to the World Bank Nicaragua's GDP was around $4.9 US billion dollars. Recently, in March 2007, Poland and Nicaragua signed an agreement to write off 30.6 million dollars which was borrowed by the Nicaraguan government in the 1980s.[72] Since the end of the war almost two decades ago, more than 350 state enterprises have been privatized. Inflation reduced from 33,500% in 1988 to 9.45% in 2006, and the foreign debt was cut in half.[73]

According to the World Bank, Nicaragua ranked as the 62nd best economy for starting a business making it the second best in Central America, after Panama.[74] Nicaragua's economy is "62.7% free" with high levels of fiscal, government, labor, investment, financial, and trade freedom.[75] It ranks as the 61st freest economy, and 14th (out of 29) in the Americas.

[edit] Coinage

During the era of the Spanish colonial rule-and for more than 50 years afterwards-Nicaragua used Spanish coins that were struck for use in the "New World". The first unique coins for Nicaragua were issued in 1878 in the peso denomination. The cordoba became Nicaragua's currency in 1912 and was initially equal in value to the U.S. dollar. The Nicaraguan unit of currency is the Córdoba (NIO) and was named after Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, its national founder. The front of each of Nicaragua's circulating coins features the national coat of arms. The five volcanoes represent the five Central American countries at the time of Nicaragua's independence, while the rainbow at the top symbolizes peace and the cap in the center is a symbol of freedom. The design is contained within a triangle to indicate equality. The back of each coin features the denomination, with the inscription "En Dios Confiamos" (In God We Trust).

[edit] Tourism

Tourism in Nicaragua is currently the second largest industry in the nation,[76] over the last 7 years tourism has grown about 70% nationwide with rates of 10%-16% annually.[77] Nicaragua has seen positive growth in the tourism sector over the last decade and is expected to become the first largest industry in 2007. The increase and growth led to the income from tourism to rise more than 300% over a period of 10 years.[78] The growth in tourism has also positively affected the agricultural, commercial, and finance industries, as well as the construction industry. Despite the positive growth throughout the last decade, Nicaragua remains the least visited nation in the region.[79][80]

Every year about 60,000 U.S. citizens visit Nicaragua, primarily business people, tourists, and those visiting relatives.[81] Some 5,300 people from the U.S. reside in the country now. The majority of tourists that visit Nicaragua are from the U.S., Central or South America, and Europe. According to the Ministry of Tourism of Nicaragua (INTUR),[82] the colonial city of Granada is the preferred spot for tourists. Also, the cities of León, Masaya, Rivas and the likes of San Juan del Sur, San Juan River, Ometepe, Mombacho Volcano, the Corn Islands, and others are main tourist attractions. In addition, ecotourism and surfing attract many tourists to Nicaragua.

According to TV Noticias (news program) on Canal 2, a Nicaragua television station, the main attractions in Nicaragua for tourists are the beaches, scenic routes, the architecture of cities such as León and Granada and most recently ecotourism and agritourism, particularly in Northern Nicaragua.[77]

[edit] Demographics

[edit] Population

According to the CIA World Factbook, Nicaragua has a population of 5,570,129; comprising mainly 69% mestizo, 17% white, 9% black and 5% amerindian; this fluctuates with changes in migration patterns. The population is 54% urban.

The most populous city in Nicaragua is the capital, Managua, with a population of 1.2 million (2005). As of 2005, over 4.4 million inhabitants live in the Pacific, Central and North regions, 2.7 in the Pacific region alone, while inhabitants in the Caribbean region reached an estimated 700,000.[83]

There is a growing expatriate community[84] the majority of whom move for business, investment or retirement from United States, Canada, Europe, Taiwan, and other countries; the majority have settled in Managua, Granada and San Juan del Sur.

Many Nicaraguans live abroad, outside of Nicaragua.

[edit] Ethnic groups

The majority of the Nicaraguan population, (86% or approximately 4.8 million people), is either Mestizo or White. 69% are Mestizos (mixed Amerindian and White) and 17% are White with the majority being of Spanish, German, Italian, or French ancestry. Mestizos and Whites mainly reside in the western region of the country.

About 9% of Nicaragua's population is black, or Afro-Nicaragüense, and mainly reside on the country's sparsely populated Caribbean or Atlantic coast. The black population is mostly composed of black English-speaking Creoles who are the descendents of escaped or shipwrecked slaves; many carry the name of Scottish settlers who brought slaves with them, such as Campbell, Gordon, Downs and Hodgeson. Although many Creoles supported Somoza because of his close association with the US, they rallied to the Sandinista cause in July 1979 only to reject the revolution soon afterwards in response to a new phase of 'mestizoisation' and imposition of central rule from Managua.[85] Nicaragua has the largest Afro Latin American population in Central America with the second largest percentage. There is also a smaller number of Garifuna, a people of mixed Carib and Arawak descent. In the mid-1980s, the government divided the department of Zelaya - consisting of the eastern half of the country - into two autonomous regions and granted the black and indigenous people of this region limited self-rule within the Republic.

The remaining 5% of Nicaraguans are Amerindians, the unmixed descendants of the country's indigenous inhabitants. Nicaragua's pre-Columbian population consisted of many indigenous groups. In the western region the Nicarao people, after whom the country is named, were present along with other groups related by culture and language to the Mayans. The Caribbean coast of Nicaragua was inhabited by indigenous peoples who were mostly chibcha related groups that had migrated from South America, primarily present day Colombia and Venezuela. These groups include the Miskitos, Ramas and Sumos. In the nineteenth century, there was a substantial indigenous minority, but this group was also largely assimilated culturally into the mestizo majority.

[edit] Immigration

In the 1800s Nicaragua experienced several waves of immigration, primarily from Europe. In particular, families from Germany, Italy, Spain, France and Belgium immigrated to Nicaragua, particularly the departments in the Central and Pacific region. As a result, the Northern cities of Esteli, Jinotega and Matagalpa have significant communities of fourth generation Germans. They established many agricultural businesses such as coffee and sugar cane plantations, newspapers, hotels and banks.

Also present is a small Middle Eastern-Nicaraguan community of Syrians, Armenians, Palestinian Nicaraguans, Jewish Nicaraguans, and Lebanese people in Nicaragua with a total population of about 30,000. There is also an East Asian community mostly consisting of Chinese, Taiwanese, and Japanese. The Chinese Nicaraguan population is estimated at around 12,000.[86] The Chinese arrived in the late 1800s but were unsubstantiated until the 1920s.

Relative to its overall population, Nicaragua has never experienced any large scale wave of immigrants. The total number of immigrants to Nicaragua, both originating from other Latin American countries and all other countries, never surpassed 1% of its total population prior to 1995. The 2005 census showed the foreign-born population at 1.2%, having risen a mere .06% in 10 years.[83]

[edit] Diaspora

The Civil War forced many Nicaraguans start lives outside of their country. Although many Nicaraguans returns after the end of the war, many people emigrated during the 1990s and the 2000s due the unemployment and the poverty. The majority of the Nicaraguan Diaspora is in Costa Rica and the United States, and today one in six Nicaraguans live in these two countries[87]. Is hard estimate the number of Nicaraguans living abroad because many of them are illegals. The table shows current statistics for certain countries:

| Country | Count |

|---|---|

| 236,000-750,000[88] | |

| 300,000[89] | |

| 2,522[90] | |

| 23,000[91] | |

| 100,000[92] | |

| Nicaraguans living abroad | At least 1,000,000[93] |

[edit] Culture

Nicaraguan culture has strong folklore, music and religious traditions, deeply influenced by European culture but enriched with Amerindian sounds and flavors. Nicaraguan culture can further be defined in several distinct strands. The Pacific coast has strong folklore, music and religious traditions, deeply influenced by Europeans. It was colonized by Spain and has a similar culture to other Spanish-speaking Latin American countries. The Caribbean coast of the country, on the other hand, was once a British protectorate. English is still predominant in this region and spoken domestically along with Spanish and indigenous languages. Its culture is similar to that of Caribbean nations that were or are British possessions, such as Jamaica, Belize, The Cayman Islands, etc. The indigenous groups that were present in the Pacific coast have largely been assimilated into the mestizo culture, however, the indigenous people of the Caribbean coast have maintained a distinct identity.

Nicaraguan music is a mixture of indigenous and European, especially Spanish, influences. Musical instruments include the marimba and others common across Central America. The marimba of Nicaragua is uniquely played by a sitting performer holding the instrument on his knees. He is usually accompanied by a bass fiddle, guitar and guitarrilla (a small guitar like a mandolin). This music is played at social functions as a sort of background music. The marimba is made with hardwood plates, placed over bamboo or metal tubes of varying lengths. It is played with two or four hammers. The Caribbean coast of Nicaragua is known for a lively, sensual form of dance music called Palo de Mayo which is very much alive all throughout the country. It is especially loud and celebrated during the Palo de Mayo festival in May The Garifuna community exists in Nicaragua and is known for its popular music called Punta.

Literature of Nicaragua can be traced to pre-Columbian times with the myths and oral literature that formed the cosmogonic view of the world that indigenous people had. Some of these stories are still known in Nicaragua. Like many Latin American countries, the Spanish conquerors have had the most effect on both the culture and the literature. Nicaraguan literature has historically been an important source of poetry in the Spanish-speaking world, with internationally renowned contributors such as Rubén Darío who is regarded as the most important literary figure in Nicaragua, referred to as the "Father of Modernism" for leading the modernismo literary movement at the end of the 19th century.[95] Other literary figures include Ernesto Cardenal, Gioconda Belli, Claribel Alegría and Jose Coronel Urtecho, among others.

El Güegüense is a satirical drama and was the first literary work of pre-Columbian Nicaragua. It is regarded as one of Latin America's most distinctive colonial-era expressions and as Nicaragua's signature folkloric masterpiece combining music, dance and theater.[95] The theatrical play was written by an anonymous author in the 16th century, making it one of the oldest indigenous theatrical/dance works of the Western Hemisphere.[96] The story was published in a book in 1942 after many centuries.[97]

[edit] Language

Central American Spanish is spoken by about 90% of the country's population. In Nicaragua the Voseo form is common, as also in Argentina, Uruguay and coastal Colombia. In the Caribbean coast many Afro-Nicaraguans and creoles speak English and creole English as their first language. Also in the Caribbean coast, many Indigenous people speak their native languages, such as the Miskito, Sumo, Rama and Garifuna language.[98] In addition, many ethnic groups in Nicaragua have maintained their ancestral languages, while also speaking Spanish or English; these include Chinese, Arabic, German, and Italian.

Nicaragua was home to 3 extinct languages, one of which was never classified. Nicaraguan Sign Language is also of particular interest to linguists.

[edit] Religion

| Religious Affiliation in Nicaragua | |

|

|

| The Metropolitan Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Managua | |

| Religion | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Roman Catholic | 58.5% |

| Evangelical | 21.6% |

| Moravian | 1.6% |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 0.9% |

| None | 15.7% |

| Other1 | 1.6% |

| 1 Includes Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism among other religions. | |

| Source: 2005 Nicaraguan Census[99] | |

Religion is a significant part of the culture of Nicaragua and is referred to in the constitution. Religious freedom, which has been guaranteed since 1939 and religious tolerance are promoted by both the Nicaraguan government and the constitution.

Nicaragua has no official religion. However, Catholic Bishops are expected to lend their authority to important state occasions, and their pronouncements on national issues are closely followed. They can also be called upon to mediate between contending parties at moments of political crisis.[100]

The largest denomination, and traditionally the religion of the majority, is Roman Catholic. However, the numbers of practicing Roman Catholics have been declining, while members of evangelical Protestant groups and Mormons have been rapidly growing in numbers since the 1990s. There are also strong Anglican and Moravian communities on the Caribbean coast.

Roman Catholicism came to Nicaragua in the sixteenth century with the Spanish conquest and remained, until 1939, the established faith. Protestantism and other Christian denominations came to Nicaragua during the nineteenth century, but only gained large followings in the Caribbean Coast during the twentieth century.

Popular religion revolves around the saints, who are perceived as intermediaries between human beings and God. Most localities, from the capital of Managua to small rural communities, honor patron saints, selected from the Roman Catholic calendar, with annual fiestas. In many communities, a rich lore has grown up around the celebrations of patron saints, such as Managua's Saint Dominic (Santo Domingo), honored in August with two colorful, often riotous, day-long processions through the city. The high point of Nicaragua's religious calendar for the masses is neither Christmas nor Easter, but La Purísima, a week of festivities in early December dedicated to the Immaculate Conception, during which elaborate altars to the Virgin Mary are constructed in homes and workplaces.[100]

[edit] Cuisine

The Cuisine of Nicaragua is a mixture of criollo food and dishes of pre-Columbian origin. The Spaniards found that the Creole people had incorporated local foods available in the area into their cuisine.[101] Traditional cuisine changes from the Pacific to the Caribbean coast; while the Pacific coast's main staple revolves around local fruits and corn, the Caribbean coast cuisine makes use of seafood and the coconut.

As in many other Latin American countries, corn is a main staple. Corn is used in many of the widely consumed dishes, such as the nacatamal, and indio viejo. Corn is also an ingredient for drinks such as pinolillo and chicha as well as sweets and desserts. In addition to corn, rice and beans are eaten very often.

Gallopinto, Nicaragua's national dish, is made with white rice and red beans that are cooked separately and then fried together. The dish has several variations including the addition of coconut oil and/or grated coconut on the Caribbean coast. Most Nicaraguans begin and end every day with Gallopinto.

Many of Nicaragua's dishes include indigenous fruits and vegetables such as jocote, mango, papaya, tamarindo, pipian, banana, avocado, yuca, and herbs such as cilantro, oregano and achiote.[101]

Nicaraguans also eat guinea pigs and tapirs, [102] iguanas and turtle eggs.

[edit] Education

Education is free for all Nicaraguans.[103] Elementary education is free and compulsory, however, many children in rural areas are unable to attend due to lack of schools and other reasons. Communities located on the Caribbean coast have access to education in their native languages.

The majority of higher education institutions are located in Managua, higher education has financial, organic and administrative autonomy, according to the law. Also, freedom of subjects is recognized.[104] Nicaragua's higher education system consists of 48 universities, and 113 colleges and technical institutes in the areas of electronics, computer systems and sciences, agroforestry, construction and trade-related services.[105] The educational system includes 1 U.S. accredited English-language university, 3 Bilingual university programs, 5 Bilingual secondary schools and dozens of English Language Institutes. In 2005, almost 400,000 (7%) of Nicaraguans held a university degree.[106] 18% of Nicaragua's total budget is invested in primary, secondary and higher education. University level institutions account for 6% of 18%.

As of 1979, the educational system was one of the poorest in Latin America.[107] Under the Somoza dictatorships, limited spending on education and generalized poverty, which forced many adolescents into the labor market, constricted educational opportunities for Nicaraguans. One of the first acts of the newly elected Sandinista government in 1980 was an extensive and successful literacy campaign, using secondary school students, university students and teachers as volunteer teachers: it reduced the overall illiteracy rate from 50.3% to 12.9% within only five months.[108] This was one of a number of large scale programs which received international recognition for their gains in literacy, health care, education, childcare, unions, and land reform.[109][110] In September 1980, UNESCO awarded Nicaragua the “Nadezhda K. Krupskaya” award for the literacy campaign. This was followed by the literacy campaigns of 1982, 1986, 1987, 1995 and 2000, all of which were also awarded by UNESCO.[111]

[edit] Sports

Baseball is the most popular sport played in Nicaragua. Although some professional Nicaraguan baseball teams have folded in the recent past, Nicaragua enjoys a strong tradition of American-style Baseball. Baseball was introduced to Nicaragua at different years during the 19th century. In the Caribbean coast locals from Bluefields were taught how to play baseball in 1888 by Albert Addlesberg, a retailer from the United States.[112] Baseball did not catch on in the Pacific coast until 1891 when a group of mostly students originating from universities of the United States formed "La Sociedad de Recreo" (Society of Recreation) where they played various sports, baseball being the most popular among them.[112] There are five teams that compete amongst themselves: Indios del Boer (Managua), Chinandega, Tiburones (Sharks) of Granada, Leon and Masaya. Players from these teams comprise the National team when Nicaragua competes internationally. The country has had its share of MLB players (including current Texas Rangers Pitcher Vicente Padilla and Boston Red Sox pitcher Devern Hansack), but the most notable is Dennis Martínez, who was the first baseball player from Nicaragua to play in Major League Baseball.[113] He became the first Latin-born pitcher to throw a perfect game, the 13th in major league history, for the Montreal Expos against the Dodgers at Dodger Stadium in 1991.[114]

Boxing is the second most popular sport in Nicaragua.[115] The country has had world champions such as Alexis Argüello and Ricardo Mayorga among others. Recently, football has gained some popularity, especially with the younger population. The Dennis Martínez National Stadium has served as a venue for both baseball and soccer but the first ever national football stadium in Managua is currently under construction.[116]

[edit] See also

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[edit] References

- ^ As shown on the Córdoba (bank notes and coins); see for example Banco Central de Nicaragua

- ^ a b c d "Nicaragua". International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2008/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2004&ey=2008&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=278&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CLP&grp=0&a=&pr.x=46&pr.y=14. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ^ a b c "Nicaragua: Precolonial Period". Library of Congress Country Studies. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ni0013). Retrieved on 2007-06-29.

- ^ "Nicaragua: VI History". Encarta. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761577584_8/Nicaragua.html. Retrieved on 2007-06-13.

- ^ "Letter of Columbus on the Fourth Voyage". American Journey. http://www.americanjourneys.org/aj-068/summary/index.asp. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ a b c "Nicaragua: History". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-214487/Nicaragua. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ "The Spanish Conquest". Library of Congress. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ni0014). Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ a b "Nicaragua Briefs: An Historic Find". Envío (Central American University - UCA). http://www.envio.org.ni/articulo/1418. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ Duncan, David Ewing, Hernando de Soto - A Savage Quest in the Americas - Book II: Consolidation, Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, 1995

- ^ Herring, Hubert, A History of Latin America - from the Beginnings to the Present - Chapter 28, Central America and Panama - Nicaragua, 1838-1909, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1968

- ^ "Foreign Relations of the United States 1912, pg. 1032ff".

- ^ "US violence for a century: Nicaragua: 1912-33". Socialist Worker. http://www.socialistworker.co.uk/art.php?id=12191. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ "Bryan–Chamorro Treaty". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9016820/Bryan-Chamorro-Treaty. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ "General Augusto C. Sandino: The Constitutional War". ViaNica. http://www.vianica.com/go/specials/16-augusto-sandino.html. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ Vukelich, Donna. "A Disaster Foretold". The Advocacy Project. http://www.advocacynet.org/news_view/news_141.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ a b c d e "The Somoza years". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-40992/Nicaragua. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ "Biographical Notes". http://www.sandino.org/bio_en.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "History of U.S. Violence Across the Globe: Washington's War Crimes (1912-33)". 2001-12-16. http://www.bulatlat.com/news/2-5/2-5-reader-arnove.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ Solo, Toni (2005-10-07). "Nicaragua: From Sandino to Chavez". Dissident Voice. http://www.dissidentvoice.org/Oct05/solo1007.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "The Somoza Dynasty" (PDF). University of Pittsburgh. pp. 1. http://www.ucis.pitt.edu/clas/nicaragua_proj/history/somoza/Hist-Somoza-dinasty.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ Lying for Empire: How to Commit War Crimes With a Straight Face" David Model, Common Courage Press, 2005

- ^ "El asalto de Somoza a los alemanes" (in Spanish). 6 January 2005. http://archivo.elnuevodiario.com.ni/2005/enero/06-enero-2005/nacional/nacional-20050106-04.html. Retrieved on 2007-07-13.

- ^ "The United States and the Founding of the United Nations...". U.S. Department of State. October 2005. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ho/pubs/fs/55407.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Sandino and Somoza". Grinnell College. http://web.grinnell.edu/LatinAmericanStudies/this.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas M (2003). "Against all odds: U.S. policy and the 1963 Central America Summit Conference". Journal of Third World Studies. pp. 11. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3821/is_200304/ai_n9173383/pg_11. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ Annis, Barbara (December 1993). "Nicaragua: Diversification and Growth, 1945-77". The Library of Congress. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ni0047). Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Headline: Nicaragua Earthquake". Vanderbilt University. 1972-12-16. http://openweb.tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/1972-12/1972-12-26-CBS-10.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-24.

- ^ "Roberto Clemente - Bio". he National Baseball Hall of Fame. http://baseballhalloffame.org/hofers_and_honorees/hofer_bios/clemente_roberto.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "A Battle Ends, a War Begins". TIME. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,946048-1,00.html. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ "The Sandinistas and the Revolution". Grinnell College. http://web.grinnell.edu/LatinAmericanStudies/this.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ a b "History of Nicaragua: The Beginning of the End". American Nicaraguan School. http://www.ans.edu.ni/Academics/history/somozatachito.html. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ^ "Timeline: Nicaragua". Stanford University. http://www.stanford.edu/group/arts/nicaragua/discovery_eng/timeline/. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ Baracco, L. (2007) Wadabagei: A Journal of the Caribbean and its Diaspora, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 4-23.

- ^ a b "Nicaragua: Growth of Opposition, 1981-83". Ciao Atlas. http://www.ciaonet.org/atlas/countries/ni_data_loc.html. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ Truver, Scott C.. "Mines and Underwater IEDs in U.S. Ports and Waterways..." (PDF). pp. 4. http://www.mast.udel.edu/873/Spring%202007/ScottTruves.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ Summary of the Order of the International Court of Justice of 10 May 1984

- ^ Nicaragua v. United States

- ^ "US Policy: Economic Embargo: The War Goes On". Envío (Central American University - UCA). http://www.envio.org.ni/articulo/2695. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ Election archive

- ^ The library of Congress Country Studies

- ^ Baker, Dean. The United States since 1980 (The World Since 1980). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 101. ISBN 0-521-86017-2.

- ^ "The Oliver North File". National Security Archive. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB113/index.htm. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ Panama Noriega's Money Machine MICHAEL S. SERRILL, Reported by Jonathan Beaty and Ricardo Chavira/Washington, '50th birthday last week' written February 1989

- ^ Noriega suffers mild stroke, hospitalized in Miami CNN December 2004

- ^ Restored version of the original "Dark Alliance" web page, San Jose Mercury News, now hosted by narconews.com

- ^ Crockett, Stephen. "Bush and Republicans vs. rule of law". The Free Press. http://www.freepress.org/departments/display/20/2006/1713. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/70/6483.pdf

- ^ International and Comparative Law Quarterly (1958), 7:758-762 Cambridge University Press Copyright © British Institute of International and Comparative Law 1958

- ^ O'GRADY, MARY. "Ortega's Comeback Schemes Roil Nicaragua". http://www.mre.gov.br/portugues/noticiario/internacional/selecao_detalhe.asp?ID_RESENHA=154683&Imprime=on. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "The Return of the Death of Communism: Nicaragua, February 1990," a chapter in Give War a Chance... by P. J. O'Rourke. Grove Press; reprint edition (November 2003, ISBN 0-8021-4031-9).

- ^ "Was February 25 a 'triumph'? National Review v. 42". Tulane University. http://lal.tulane.edu/RESTRICTED/CABIB/nicabib_.txt. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "El Sandinista Daniel Ortega se convierte de nuevo en presidente de Nicaragua" (in Spanish). El Mundo. 2006-11-08. http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2006/11/08/internacional/1162945503.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ Dennis, Gilbert (December 1993). "Social conditions of Nicaragua". The Library of Congress. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ni0035). Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Nicaragua: Political profile". http://www.alertnet.org/printable.htm?URL=/db/cp/nicaragua.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ Thompson, Ginger (2005-04-06). "U.S. fears comeback of an old foe in Nicaragua". International Herald Tribune. pp. 3. http://www.iht.com/articles/2005/04/05/news/nica.php. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Nicaragua 'creeping coup' warning". BBC News. 2005-09-30. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/4296818.stm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ B. Frazier, Joseph (2006-11-18). "Nicaraguan President Signs Abortion Ban". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/11/18/AR2006111800351.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- ^ "Bolaños Will Move To The National Assembly After All". Envío Magazine. November 2006. http://www.envio.org.ni/articulo/3439. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Background and socio-economic context" (PDF). pp. 9. http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/vam/wfp073961.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Large Lakes of the World". http://www.factmonster.com/ipka/A0001777.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- ^ "The Nature Conservancy in Nicaragua". http://www.nature.org/wherewework/centralamerica/nicaragua/. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- ^ White, Richard L. (2004-08-24). "Pittsburghers find once war-ravaged country is a good place to invest". Post Gazette. http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/04237/366377.stm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Bosawas Bioreserve Nicaragua". http://www.abc.net.au/rn/scienceshow/stories/2006/1718459.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- ^ "General Information - Nicaragua: Economy". http://centralamerica.com/nicaragua/info/general.htm#economy. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Nicaragua: Economy". CIA World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/nu.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Rank Order - GDP - per capita (PPP)". CIA World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2004rank.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Social indicators: Per capita GDP". United Nations. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/socind/inc-eco.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ http://www.pnud.org.ni/noticias/343

- ^ http://hdrstats.undp.org/indicators/24.html

- ^ Silva, José Adán. "NICARAGUA: Name and Identity for Thousands of Indigenous Children". IPS. http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=43760. Retrieved on 2008-09-12.

- ^ Tartter, Jean R.. "The Nicaraguan Resistence". Country Studies (Library of Congress). http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?cstdy:10:./temp/~frd_famN::. Retrieved on 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Poland forgives nearly 31 million dollars of debt owed by Nicaragua". People's Daily Online. 2007-03-21. http://english.people.com.cn/200703/31/eng20070331_362713.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Nicaragua:Economy". U.S. State Department. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/1850.htm. Retrieved on 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Economy Rankings: Doing Business". World Bank. http://www.doingbusiness.org/EconomyRankings/. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Index Of Economic Freedom: Nicaragua". Heritage.org. http://www.heritage.org/research/features/index/country.cfm?id=Nicaragua. Retrieved on 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Travel And Tourism in Nicaragua". Euromonitor International. http://www.euromonitor.com/Travel_And_Tourism_in_Nicaragua. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ a b Alemán, Giselle. "Turismo en Nicaragua: aportes y desafios parte I" (in Spanish). Canal 2. http://www.canal2tv.com/Noticias/Marzo%202007/turismo%20con%20gran%20empuje%20en%20Nicaragua.html. Retrieved on 2007-07-29.

- ^ "A Dynamic Economy: Dynamic Sectors of the Economy; Tourism". ProNicaragua. http://www.pronicaragua.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=25&Itemid=98. Retrieved on 2007-08-01.

- ^ Travelotica.com Nicaragua Travel Guide

- ^ TransitionsAbroad.com Living Abroad in Nicaragua: Nicaragua’s Evolution

- ^ "Background Note: Nicaragua; Economy". U.S. State Department. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/1850.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Ministry of Tourism of Nicaragua". INTUR. http://www.intur.gob.ni/. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ a b "VIII Censo de Poblacion y IV de Vivienda" (in Spanish) (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. October 2005. http://www.inec.gob.ni/censos2005/ResumenCensal/RESUMENCENSAL.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-07-07.

- ^ "Expatriates of Nicaragua". Nicaragua.com. http://www.nicaragua.com/expatriates/. Retrieved on 2007-07-30.

- ^ Baracco, L. (2005) Nicaragua: The Imagining of a Nation. From Nineteenth-Century Liberals to Twentieth-Century Sandinistas (New York, Algora Publishing). See especially chapter 6 'From Acquiescence to Ethnic Militancy: Costeno Responses to Sandinista Anti-Imperialist Nationalism'.

- ^ "Nicaragua: People groups". Joshua Project. http://www.joshuaproject.net/countries.php?rog3=NU. Retrieved on 2007-03-26.

- ^ http://www.thedialogue.org/PublicationFiles/The%20Nicaragua%20case_M%20Orozco2%20REV.pdf

- ^ http://www.facesofcostarica.com/economics/gonzalez.htm

- ^ http://www.thedialogue.org/PublicationFiles/The%20Nicaragua%20case_M%20Orozco2%20REV.pdf

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immigration_to_Mexico

- ^ http://www.thedialogue.org/PublicationFiles/The%20Nicaragua%20case_M%20Orozco2%20REV.pdf

- ^ http://www.thedialogue.org/PublicationFiles/The%20Nicaragua%20case_M%20Orozco2%20REV.pdf

- ^ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTLACREGTOPGENDER/Resources/migracionresumido.pdf

- ^ "Traditional Nicaraguan Costumes: Mestizaje Costume". ViaNica.com. http://www.vianica.com/go/specials/19-traditional-nicaraguan-costumes.html. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ^ a b "Showcasing Nicaragua's Folkloric Masterpiece - El Gueguense - and Other Performing and Visual Arts". Encyclopedia.com. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G1-150984344.html. Retrieved on 2007-08-03.

- ^ "Native Theatre: El Gueguense". Smithsonian Institution. http://www.nmai.si.edu/calendar/index.asp?month=10&year=2006&day=22. Retrieved on 2007-08-03.

- ^ "El Güegüense o Macho Ratón". ViaNica. http://www.vianica.com/go/specials/21-el-gueguense-macho-raton.html. Retrieved on 2007-08-03.

- ^ "Languages of Nicaragua". Ethnologue. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=NI. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "2005 Nicaraguan Census" (in Spanish) (PDF). National Institute of Statistics and Census of Nicaragua (INEC): pp. 42-43. http://www.inec.gob.ni/censos2005/ResumenCensal/Resumen2.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-10-30.

- ^ a b Dennis, Gilbert. "Nicaragua: Religion". Country Studies (Library of Congress). http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ni0040). Retrieved on 2007-10-30.

- ^ a b "Try the culinary delights of Nicaragua cuisine". Nicaragua.com. http://www.nicaragua.com/cuisine/. Retrieved on 2006-05-08.

- ^ http://www.vivatravelguides.com/central-america/nicaragua/nicaragua-articles/gallo-pinto/

- ^ Liu, Dan (2006-12-06). "Nicaragua's new gov't to enforce free education". CHINA VIEW. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2006-12/06/content_5442752.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Nicaragua Education". http://www.nicaragua.com/culture/education/. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Human Capital: Educationand Training". ProNicaragua. http://www.pronicaragua.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=27&Itemid=87. Retrieved on 2007-08-01.

- ^ "Central American Countries of the Future 2005/2006". 2005-08-01. http://www.pronicaragua.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=27&Itemid=87. Retrieved on 2007-08-01.

- ^ Gilbert, Dennis. "Nicaragua: Education". Country Studies (Library of Congress). http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ni0036). Retrieved on 2007-07-02.

- ^ Hanemann, Ulrike. "Nicaragua’s Literacy Campaign". UNESCO. http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/file_download.php/67b39f3aaf8f20da06be3c6a4e4c6dfeHanemann_U.doc. Retrieved on 2007-07-02.

- ^ "Historical Background of Nicaragua". Stanford University. http://www.stanford.edu/group/arts/nicaragua/discovery_eng/history/background.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Nicaragua Pre-election Delegation Report". Global Exchange. http://www.globalexchange.org/tours/NicaraguaReportOct2001.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ B. Arrien, Juan. "Literacy in Nicaragua" (PDF). UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001459/145937e.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-08-01.

- ^ a b Villa, Beto. "LA HISTORIA DEL BÉISBOL EN LATINOAMERICA: Nicaragua" (in Spanish). Latino Baseball. http://latinobaseball.com/cwb-history.php. Retrieved on 2007-07-29.

- ^ Washburn, Gary. "'El Presidente' happy in new job". Major League Baseball. http://baltimore.orioles.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20050220&content_id=946722&vkey=news_bal&fext=.jsp&c_id=bal. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ "Baseball's Perfect Games: Dennis Martinez, Montreal Expos". The BASEBALL Page.com. http://www.thebaseballpage.com/stats/lists_feats/perfect_games.htm. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ^ "Salon de la Fama: Deportes en Nicaragua" (in Spanish). http://www.manfut.org/museos/deportes1.html. Retrieved on 2007-07-30.

- ^ "Like clockwork in Nicaragua". FIFA. http://www.fifa.com/en/development/goal/index/0,1223,104011,00.html?articleid=104011. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ Christopher Andrew, Vasili Mitrokhin. The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World, Basic Books, September 20, 2005.

- ^ Matilde Zimmermann. Sandinista, Duke University Press, 2000.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth addition, Ed. Peter N. Stearns, 2001. p. 954

- This article contains material from the U.S. Department of State's Background Notes which, as a US government publication, is in the public domain.

[edit] Bibliography

[edit] External links

![]() Textbooks from Wikibooks

Textbooks from Wikibooks

![]() Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote

![]() Source texts from Wikisource

Source texts from Wikisource

![]() Images and media from Commons

Images and media from Commons

![]() News stories from Wikinews

News stories from Wikinews

- Government

- General information

- Nicaragua entry at The World Factbook

- Nicaragua at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Nicaragua at the Open Directory Project

- Wikimedia Atlas of Nicaragua

- Maps from WorldAtlas.com

- Nicaraguaportal: Official informations of the Honorary Consulate of Nicaragua

- Travel

- Real Estate

- NicaFSBO: Real estate listings by owners

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||