Vladimir Putin

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin

Влади́мир Влади́мирович Пу́тин |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 8 May 2008 |

|

| President | Dmitry Medvedev |

| Deputy | Viktor Zubkov Igor Shuvalov |

| Preceded by | Viktor Zubkov |

| In office 9 August 1999 – 7 May 2000 |

|

| President | Boris Yeltsin |

| Preceded by | Sergei Stepashin |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Kasyanov |

|

|

|

| In office 7 May 2000 – 7 May 2008 Acting: 31 December 1999 – 7 May 2000 |

|

| Prime Minister | Mikhail Kasyanov Viktor Khristenko (Acting) Mikhail Fradkov Viktor Zubkov |

| Preceded by | Boris Yeltsin |

| Succeeded by | Dmitry Medvedev |

|

|

|

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 7 May 2008 |

|

| Preceded by | Boris Gryzlov |

|

Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Union of Russia and Belarus

|

|

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 27 May 2008 |

|

|

|

|

| Born | 7 October 1952 Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia) |

| Political party | CPSU (prior 1991) Non-partisan (since 1991) United Russia (Chairman non-member)[1] |

| Spouse | Lyudmila Putina[2] |

| Children | Mariya (1985), Yekaterina (1986) |

| Alma mater | Leningrad State University, now Saint Petersburg State University |

| Religion | Russian Orthodox |

| Signature | |

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (Russian: Влади́мир Влади́мирович Пу́тин Russian pronunciation: [vlɐˈdʲimʲɪr vlɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪt͡ɕ ˈputʲɪn]; born 7 October 1952 in Leningrad, USSR; now Saint Petersburg, Russia) was the second President of Russia and is the current Prime Minister of Russia as well as chairman of United Russia and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Union of Russia and Belarus. He became acting President on 31 December 1999, when president Boris Yeltsin resigned in a surprising move, and then Putin won the 2000 presidential election. In 2004, he was re-elected for a second term lasting until 7 May 2008.

Due to constitutionally mandated term limits, Putin was ineligible to run for a third consecutive Presidential term. After the victory of his successor, Dmitry Medvedev, in the 2008 presidential elections, he was then nominated by the latter to be Russia's Prime Minister; Putin took the post on 8 May 2008.

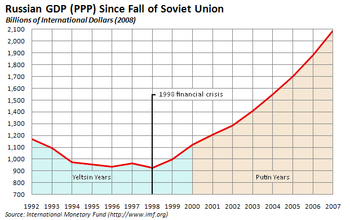

Throughout his presidential terms and into his second term as Prime Minister, Putin has enjoyed high approval ratings amongst the Russian public. During his eight years in office, on the back of Yeltsin-era structural reforms, steadily rising oil price and cheap credit from western banks,[3][4][5] Russia's economy bounced back from crisis, seeing GDP increase sixfold (72% in PPP),[6][7] poverty cut more than half[8][9][10] and average monthly salaries increase from $80 to $640, or by 150% in real rates.[6][11] Analysts have described Putin's economic reforms as impressive.[12] During his presidency, Putin passed into law a series of fundamental reforms, including a flat income tax of 13 percent, a reduced profits tax, and new land and legal codes.[12] Putin's prudent economic policies have received praise from Western economists.[13] At the same time, his conduct in office has been questioned by domestic political opposition, foreign governments and human rights organizations for leading the Second Chechen War, for his record on internal human rights and freedoms, and for his alleged bullying of the former Soviet Republics. A new group of business magnates controlling significant swathes of Russia's economy, such as Gennady Timchenko, Vladimir Yakunin, Yuriy Kovalchuk, Sergey Chemezov, with close personal ties to Putin, emerged according to media reports.[14][15][16][17][18][19][20] Corruption increased and assumed "systemic and institutionalised form", according to a report by Boris Nemtsov as well as other sources.[21][22][23][24][25][26]

Contents |

[edit] Early life

Putin was born on 7 October 1952 in Leningrad, to parents Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin (1911 – 1999) and Maria Ivanovna Shelomova (1911 – 1998). His mother was a factory worker, and his father was a conscript in the Soviet Navy, where he served in the submarine fleet in the early 1930s,[27] subsequently serving with the NKVD in a sabotage group during World War II.[28] Two elder brothers were born in the mid – 1930s; one died within a few months of birth; the second succumbed to diphtheria during the siege of Leningrad. His paternal grandfather, Spiridon Ivanovich Putin (1879 – 1965) was employed at Vladimir Lenin's dacha (Gorki) as a cook, and after Lenin's death in 1924, he continued to work for Lenin's wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya. He would later cook for Joseph Stalin when the Soviet leader visited one of his dachas in the Moscow region. Spiridon later was employed at a dacha belonging to the Moscow City Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, at which the young Putin would visit him.[29]

His autobiography, Ot Pervogo Litsa, (English: In the First Person)[27] which is based on Putin's interviews, speaks of humble beginnings, including early years in a communal apartment in Leningrad. On 1 September 1960 he started at School No. 193 at Baskov Lane, just across from his house. By fifth grade he was one of a few in a class of more than 45 pupils who was not yet a member of the Pioneers, largely because of his rowdy behavior. In sixth grade he started taking sport seriously in the form of sambo and then judo. In his youth, Putin was eager to emulate the intelligence officer characters played on the Soviet screen by actors such as Vyacheslav Tikhonov and Georgiy Zhzhonov.

Putin graduated from the International Law branch of the Law Department of the Leningrad State University in 1975, writing his final thesis on international law.[30] While at university he became a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and remained a member until the party was dissolved in December 1991.[31] Also at the University he met Anatoly Sobchak, who later played important role in Putin's career.[citation needed]

[edit] KGB career

Putin joined the KGB in 1975 upon graduation from university, and underwent a year's training at the 401st KGB school in Okhta, Leningrad. He then went on to work briefly in the Second Department (counter-intelligence) before he was transferred to the First Department, where amongst his duties was the monitoring of foreigners and consular officials in Leningrad, while using the cover of being a police officer with the CID.[32][33] According to Yuri Felshtinsky and Vladimir Pribylovsky, he served at the Fifth Directorate of the KGB, which combated political dissent in the Soviet Union.[34] He then received an offer to transfer to foreign intelligence First Chief Directorate of the KGB and was sent for additional year long training to the Dzerzhinsky KGB Higher School in Moscow and then in the early eighties—the Red Banner Yuri Andropov KGB Institute in Moscow (now the Academy of Foreign Intelligence).

From 1985 to 1990 the KGB stationed Putin in Dresden, East Germany.[35] Following the collapse of the East German regime, Putin was recalled to the Soviet Union and returned to Leningrad, where in June 1991 he assumed a position with the International Affairs section of Leningrad State University, reporting to Vice-Rector Yuriy Molchanov. In his new position, Putin maintained surveillance on the student body and kept an eye out for recruits. It was during his stint at the university that Putin grew reacquainted with Anatoly Sobchak, then mayor of Leningrad. Sobchak served as an Assistant Professor during Putin's university years and was one of Putin's lecturers. Putin formally resigned from the state security services on 20 August 1991, during the KGB-supported abortive putsch against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev.

[edit] Early political career

In May 1990, Putin was appointed Mayor Sobchak's advisor on international affairs. On 28 June 1991, he was appointed head of the Committee for External Relations of the Saint Petersburg Mayor's Office, with responsibility for promoting international relations and foreign investments. The Committee was also used to register business ventures in Saint Petersburg. Less than one year after taking control of the committee, Putin was investigated by a commission of the city legislative council. Commission deputies Marina Salye and Yury Gladkov concluded that Putin understated prices and issued licenses permitting the export of non-ferrous metals valued at a total of $93 million in exchange for food aid from abroad that never came to the city.[36][37][38][39][40] The commission recommended Putin be fired, but there were no immediate consequences. Putin remained head of the Committee for External Relations until 1996. While heading the Committee for External Relations, from 1992 to March 2000 Putin was also on the advisory board of the German real estate holding Saint Petersburg Immobilien und Beteiligungs AG (SPAG) which has been investigated by German prosecutors for money laundering.[41][42][43][44][45]

From 1994 to 1997, Putin was appointed to additional positions in the Saint Petersburg political arena. In March 1994 he became first deputy head of the administration of the city of Saint Petersburg. In 1995 (through June 1997) Putin led the Saint Petersburg branch of the pro-government Our Home Is Russia political party.[46] During this same period from 1995 through June 1997 he was also the head of the Advisory Board of the JSC Newspaper Sankt-Peterburgskie Vedomosti.[46]

In 1996, Anatoly Sobchak lost the Saint Petersburg mayoral election to Vladimir Yakovlev. Putin was called to Moscow and in June 1996 assumed position of a Deputy Chief of the Presidential Property Management Department headed by Pavel Borodin. He occupied this position until March 1997. On 26 March 1997 President Boris Yeltsin appointed Putin deputy chief of Presidential Staff, which he remained until May 1998, and chief of the Main Control Directorate of the Presidential Property Management Department (until June 1998).

On 27 June 1997, at the Saint Petersburg Mining Institute Putin defended his Candidate of Science dissertation in economics titled "The Strategic Planning of Regional Resources Under the Formation of Market Relations".[47] According to Clifford G Gaddy, a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution, 16 of the 20 pages that open a key section of Putin’s work were copied either word for word or with minute alterations from a management study, Strategic Planning and Policy, written by US professors William King and David Cleland and translated into Russian by a KGB-related institute in the early 1990s.[48] 6 diagrams and tables were also copied.[49]

On 25 May 1998, Putin was appointed First Deputy Chief of Presidential Staff for regions, replacing Viktoriya Mitina; and, on 15 July, the Head of the Commission for the preparation of agreements on the delimitation of power of regions and the federal center attached to the President, replacing Sergey Shakhray. After Putin's appointment, the commission completed no such agreements, although during Shakhray's term as the Head of the Commission there were 46 agreements signed.[50] On 25 July 1998 Yeltsin appointed Vladimir Putin head of the FSB (one of the successor agencies to the KGB), the position Putin occupied until August 1999. He became a permanent member of the Security Council of the Russian Federation on 1 October 1998 and its Secretary on 29 March 1999. In April 1999, FSB Chief Vladimir Putin and Interior Minister Sergei Stepashin held a televised press conference in which they discussed a video that had aired nationwide 17 March on the state-controlled Russia TV channel which showed a naked man very similar to the Prosecutor General of Russia, Yury Skuratov, in bed with two young women. Putin claimed that expert FSB analysis proved the man on the tape to be Skuratov and that the orgy had been paid for by persons investigated for criminal offences.[51][52] Skuratov had been adversarial toward President Yeltsin and had been aggressively investigating government corruption[53].

On 15 June 2000, The Times reported that Spanish police discovered that Putin had secretly visited a villa in Spain belonging to the oligarch Boris Berezovsky on up to five different occasions in 1999.[54]

[edit] Prime Ministry (1999)

On 9 August 1999, Vladimir Putin was appointed one of three First Deputy Prime Ministers, which enabled him later on that day, as the previous government led by Sergei Stepashin had been sacked, to be appointed acting Prime Minister of the Government of the Russian Federation by President Boris Yeltsin.[55] Yeltsin also announced that he wanted to see Putin as his successor. Later, that same day, Putin agreed to run for the presidency.[56] On 16 August, the State Duma approved his appointment as Prime Minister with 233 votes in favour (vs. 84 against, 17 abstained),[57] while a simple majority of 226 was required, making him Russia's fifth PM in fewer than eighteen months. On his appointment, few expected Putin, virtually unknown to the general public, to last any longer than his predecessors. Yeltsin's main opponents and would-be successors, Moscow Mayor Yuriy Luzhkov and former Chairman of the Russian Government Yevgeniy Primakov, were already campaigning to replace the ailing president, and they fought hard to prevent Putin's emergence as a potential successor. Putin's law-and-order image and his unrelenting approach to the renewed crisis in Chechnya soon combined to raise his popularity and allowed him to overtake all rivals.

Putin's rise to public office in August 1999 coincided with an aggressive resurgence of the near-dormant conflict in the North Caucasus, when a number of Chechens invaded a neighboring region starting the War in Dagestan. Both in Russia and abroad, Putin's public image was forged by his tough handling of the war. On assuming the role of acting President on 31 December 1999, Putin went on a previously scheduled visit to Russian troops in Chechnya. In 2003, a controversial referendum was held in Chechnya adopting a new constitution which declares the Republic as a part of Russia. Chechnya has been gradually stabilized with the parliamentary elections and the establishment of a regional government.[58][59] Throughout the war Russia has severely disabled the Chechen rebel movement, although sporadic violence still occurs throughout the North Caucasus.[60]

While not formally associated with any party, Putin pledged his support to the newly formed Unity Party,[61] which won the second largest percentage of the popular vote (23.3%) in the December 1999 Duma elections, and in turn he was supported by it.

[edit] Presidency

[edit] First term (2000 – 2004)

His rise to Russia's highest office ended up being even more rapid: on 31 December 1999, Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned and, according to the constitution, Putin became Acting President of the Russian Federation.

The first Decree that Putin signed 31 December 1999, was the one "On guarantees for former president of the Russian Federation and members of his family".[62][63] This ensured that "corruption charges against the outgoing President and his relatives" would not be pursued, although this claim is not strictly verifiable.[64] Later on 12 February 2001 Putin signed a federal law on guarantees for former presidents and their families, which replaced the similar decree. In 1999, Yeltsin and his family were under scrutiny for charges related to money-laundering by the Russian and Swiss authorities.[65]

While his opponents had been preparing for an election in June 2000, Yeltsin's resignation resulted in the elections being held within three months, in March.[citation needed] Presidential elections were held on 26 March 2000; Putin won in the first round.[citation needed]

Vladimir Putin was inaugurated president on 7 May 2000. He appointed Financial minister Mikhail Kasyanov as his Prime minister. Having announced his intention to consolidate power in the country into a strict vertical, in May 2000 he issued a decree dividing 89 federal subjects of Russia between 7 federal districts overseen by representatives of him in order to facilitate federal administration. In July 2000, according to a law proposed by him and approved by the Russian parliament, Putin also gained the right to dismiss heads of the federal subjects.

During his first term in office, he moved to curb the political ambitions of some of the Yeltsin-era oligarchs such as former Kremlin insider Boris Berezovsky, who had "helped Mr Putin enter the family, and funded the party that formed Mr Putin's parliamentary base", according to BBC profile.[66][67] At the same time, according to Vladimir Solovyev, it was Alexey Kudrin who was instrumental in Putin's assignment to the Presidential Administration of Russia to work with Pavel Borodin,[68] and according to Solovyev, Berezovsky was proposing Igor Ivanov rather than Putin as a new president.[69] A new group of business magnates, such as Gennady Timchenko, Vladimir Yakunin, Yuriy Kovalchuk, Sergey Chemezov, with close personal ties to Putin, emerged. Corruption grew by the magnitude of several times and assumed "systemic and institutionalised" form, according to a report by Boris Nemtsov as well as other sources.[70][71][72][73][74][75] Corruption was characterized by Putin himself as "the most wearying and difficult to resolve" problem he encountered during his two terms in office.[76]

The first major challenge to Putin's popularity came in August 2000, when he was criticised for his alleged mishandling of the Kursk submarine disaster.[77]

In December 2000, Putin sanctioned the law to change the National Anthem of Russia. At the time the Anthem had music by Glinka and no words. The change was to restore (with a minor modification) the music of the post-1944 Soviet anthem by Alexandrov, while the new text was composed by Mikhalkov.[78][79]

Many in the Russian press and in the international media warned that the death of some 130 hostages in the special forces' rescue operation during the 2002 Moscow theater hostage crisis would severely damage President Putin's popularity. However, shortly after the siege had ended, the Russian president was enjoying record public approval ratings - 83% of Russians declared themselves satisfied with Putin and his handling of the siege.[80]

The arrest in early July 2003 of Platon Lebedev, a Mikhail Khodorkovsky partner and second largest shareholder in Yukos, on suspicion of illegally acquiring a stake in a state-owned fertilizer firm, Apatit, in 1994, foreshadowed what by the end of the year became a full-fledged prosecution of Yukos and its management for fraud, embezzlement and tax evasion.

A few month before the elections, Putin fired Kasyanov's cabinet and appointed relatively obscure Mikhail Fradkov to his place. Sergey Ivanov became the first civilian in Russia to take Defence Minister position.

[edit] Second term (2004 – 2008)

On 14 March 2004, Putin was re-elected to the presidency for a second term, receiving 71% of the vote.

By the beginning of Putin's second term he had undermined every independent source of political power in Russia, decreasing the degree of pluralism in the Russian society.[81]

Following the Beslan school hostage crisis, in September 2004 Putin suggested the creation of the Public Chamber of Russia and launched an initiative to replace the direct election of the Governors and Presidents of the Federal subjects of Russia with a system whereby they would be proposed by the President and approved or disapproved by regional legislatures.[82][83] He also initiated the merger of a number of federal subjects of Russia into larger entities. Whilst some in Beslan blamed Putin personally for the massacre in which hundreds died,[84] his overall popularity in Russia did not suffer.[citation needed]

According to various Russian and western media reports, one of the major domestic issue concerns for President Putin were the problems arising from the ongoing demographic and social trends in Russia, such as the death rate being higher than the birth rate, cyclical poverty, and housing concerns. In 2005, National Priority Projects were launched in the fields of health care, education, housing and agriculture. In his May 2006 annual speech, Putin proposed increasing maternity benefits and prenatal care for women. Putin was strident about the need to reform the judiciary considering the present federal judiciary "Sovietesque", wherein many of the judges hand down the same verdicts as they would under the old Soviet judiciary structure, and preferring instead a judiciary that interpreted and implemented the code to the current situation. In 2005, responsibility for federal prisons was transferred from the Ministry of Internal Affairs to the Ministry of Justice. The most high-profile change within the national priority project frameworks was probably the 2006 across-the-board increase in wages in healthcare and education, as well as the decision to modernise equipment in both sectors in 2006 and 2007.[85]

One of the most controversial aspects of Putin's second term was the continuation of the criminal prosecution of Russia's richest man, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, President of YUKOS, for fraud and tax evasion. While much of the international press saw this as a reaction against Khodorkovsky's funding for political opponents of the Kremlin, both liberal and communist, the Russian government had argued that Khodorkovsky was engaged in corrupting a large segment of the Duma to prevent changes in the tax code aimed at taxing windfall profits and closing offshore tax evasion vehicles. Khodorkovsky's arrest was met positively by the Russian public, who see the oligarchs as thieves who were unjustly enriched and robbed the country of its natural wealth.[86] Many of the initial privatizations, including that of Yukos, are widely believed to have been fraudulent – Yukos, valued at some $30 billion in 2004, had been privatized for $110 million – and like other oligarchic groups, the Yukos-Menatep name has been frequently tarred with accusations of links to criminal organizations. Tim Osborne of GML, the majority owner of Yukos, said in February 2008: "Despite claims by President Vladimir Putin that the Kremlin had no interest in bankrupting Yukos, the company's assets were auctioned at below-market value. In addition, new debts suddenly emerged out of nowhere, preventing the company from surviving. The main beneficiary of these tactics was Rosneft. It is clearer now than ever that the expropriation of Yukos was a ploy to put key elements of the energy sector in the hands of Putin's retinue. Moreover, the Yukos affair marked a turning point in Russia's commitment to domestic property rights and the rule of law."[87] The fate of Yukos was seen by western media as a sign of a broader shift toward a system normally described as state capitalism,[88][89] Against the backdrop of the Yukos saga, questions were raised about the actual destination of $13.1 billion[90] remitted in October 2005 by the state-run Gazprom as payment for 75.7% stake in Sibneft to Millhouse-controlled offshore accounts,[91] after a series of generous dividend payouts and another $3 billion received from Yukos in a failed merger in 2003.[92] In 1996, Roman Abramovich and Boris Berezovsky had acquired the controlling interest in Sibneft for $100 million within the controversial loans-for-shares program.[93] Some prominent Yeltsin-era billionaires, such as Sergey Pugachyov, are reported to continue to enjoy close relationship with Putin's Kremlin.[94]

Although Russia's state intervention in the economy had been usually heavily criticized in the West, a study by Bank of Finland’s Institute for Economies in Transition (BOFIT) in 2008 showed that state intervention had had a positive impact to corporate governance of many companies in Russia: the formal indications of the quality of corporate governance in Russia were higher in companies with state control or with a stake held by the government.[95]

Since February 2006, the political philosophy of Putin's administration has often been described as a "Sovereign democracy", the term being used both with positive and pejorative connotations. First proposed by Vladislav Surkov in February 2006, the term quickly gained currency within Russia and arguably unified various political elites around it. According to its proponents' interpretation, the government's actions and policies ought above all to enjoy popular support within Russia itself and not be determined from outside the country.[96][97] However, as implied by expert of the Carnegie Endowment Masha Lipman, "Sovereign democracy is a Kremlin coinage that conveys two messages: first, that Russia's regime is democratic and, second, that this claim must be accepted, period. Any attempt at verification will be regarded as unfriendly and as meddling in Russia's domestic affairs." [98] Some[who?] Western observers derided the term as a subterfuge to mask what is otherwise known as dictatorship.[99]

During the term, Putin was widely criticized in the West and also by Russian liberals for what many observers considered a wide-scale crackdown on media freedom in Russia. Since the early 1990s, a number of Russian reporters who have covered the situation in Chechnya, contentious stories on organized crime, state and administrative officials, and large businesses have been killed.[100][101] On 7 October 2006, Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist who ran a campaign exposing corruption in the Russian army and its conduct in Chechnya, was shot in the lobby of her apartment building. The death of Politkovskaya triggered an outcry of criticism of Russia in the Western media, with accusations that, at best, Putin has failed to protect the country's new independent media.[102] [103] When asked about Politkovskaya murder in his interview with the German TV channel ARD, Putin said that her murder brings much more harm to the Russian authorities than her publications.[104] In January 2008, Oleg Panfilov, head of the Center for Journalism in Extreme Situations, claimed that a system of "judicial terrorism" had started against journalists under Putin and that more than 300 criminal cases had been opened against them over the past six years.[105]

At the same time, according to 2005 research by VCIOM, the share of Russians approving censorship on TV grew in a year from 63% to 82%; sociologists believed that Russians were not voting in favor of press freedom suppression, but rather for expulsion of ethically doubtful material (such as scenes of violence and sex).[106]

In June 2007, Putin organised a conference for history teachers to promote a high-school teachers manual called A Modern History of Russia: 1945-2006: A Manual for History Teachers which portrays Joseph Stalin as a cruel but successful leader. Putin said at the conference that the new manual will "help instill young people with a sense of pride in Russia", and he argued that Stalin's purges pale in comparison to the United States' atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At a memorial for Stalin's victims, Putin said that while Russians should "keep alive the memory of tragedies of the past, we should focus on all that is best in the country."[107]

In a 2007 interview with newspaper journalists from G8 countries, Putin spoke out in favor of a longer presidential term in Russia, saying "a term of five, six or seven years in office would be entirely acceptable".[108][109]

On 12 September 2007, Russian news agencies reported that Putin dissolved the government upon the request of Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov. Fradkov commented that it was to give the President a "free hand" to make decisions in the run-up to the parliamentary election. Viktor Zubkov was appointed the new prime minister.[110]

In December 2007, United Russia won 64.24% of the popular vote in their run for State Duma according to election preliminary results.[111] Their closest competitor, the Communist Party of Russia, won approximately 12% of votes.[112] United Russia's victory in December 2007 elections was seen by many as an indication of strong popular support of the then Russian leadership and its policies.[113][114]

The end of 2007 saw what both Russian and Western analysts viewed as an increasingly bitter infighting between various factions of the siloviki that make up a significant part of Putin's inner circle.[115][116][117][118][119][120][121][122]

In December 2007, the Russian sociologist Igor Eidman (VCIOM) qualified the regime that had solidified under Putin as "the power of bureaucratic oligarchy" which had "the traits of extreme right-wing dictatorship — the dominance of state-monopoly capital in the economy, silovoki structures in governance, clericalism and statism in ideology".[123] Some analysts assess the socio-economic system which has emerged in Russia as profoundly unstable and the situation in the Kremlin after Dmitry Medvedev's nomination as fraught with a coup d'état, as "Putin has built a political construction that resembles a pyramid which rests on its tip, rather than on its base".[124][125]

Gregory Feifer wrote in February 2008: "The main lesson we should have learned from Putin's eight years in office is a recognition that under the traditional Russian political system that he has revitalized, not only do officials not mean what they say, but also that obfuscation is essential to the way it all works ... Putin's playing of the Russian political game has been virtuosic."[126] On the eve of his stepping down as president the FT editorialised: "Mr Putin will remain Russia’s real ruler for some time to come. And the ex-KGB men he promoted will stay close to the seat of power."[127]

On 8 February 2008, Putin delivered a speech before the expanded session of the State Council headlined "On the Strategy of Russia's Development until 2020",[128] which was interpreted by the Russian media as his "political bequest". The speech was largely devoted to castigating the state of affairs in the 1990s and setting ambitious targets of economic growth by 2020.[129] He also condemned the expansion of NATO and the US plan to include Poland and the Czech Republic in a missile defence shield and promised that "Russia has, and always will have, responses to these new challenges".[130]

In his last days in office he was reported to have taken a series of steps to re-align the regional bureaucracy to make the governors report to the prime minister rather than the president.[131][132] The presidential site explained that "the changes... bear a refining nature and do not affect the essential positions of the system. The key role in estimating the effectiveness of activity of regional authority still belongs to President of the Russian Federation."

[edit] Internal policy

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until the dispute is resolved. (June 2008) |

| This section may stray from the topic of the article. Please help improve this section or discuss this issue on the talk page. |

Under the Putin administration the economy made real gains of an average 7% per year (2000: 10%, 2001: 5.7%, 2002: 4.9%, 2003: 7.3%, 2004: 7.1%, 2005: 6.5%, 2006: 6.7%, 2007: 8.1%), making it the 7th largest economy in the world in purchasing power. Russia's nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased 6 fold, climbing from 22nd to 10th largest in the world. In 2007, Russia's GDP exceeded that of Russian SFSR in 1990, meaning it has overcome the devastating consequences of the 1998 financial crisis and preceding recession in the 1990s.[9]

During Putin's eight years in office, industry grew by 76%, investments increased by 125%,[9] and agricultural production and construction increased as well. Real incomes more than doubled and the average monthly salary increased sevenfold from $80 to $540.[6][10][133] From 2000 to 2006 the volume of consumer credit increased 45 times[134][135] and the middle class grew from 8 million to 55 million. The number of people living below the poverty line decreased from 30% in 2000 to 14% in 2008.[9][136][137] A number of large-scale reforms in retirement (2002), banking (2001–2004), tax (2000–2003), the monetization of benefits (2005) and others have taken place.

In 2001 Putin, who has advocated liberal economic policies, introduced flat tax rate of 13%[138][139]; the corporate rate of tax was also reduced from 35 percent to 24 percent; [138] Small businesses also get better treatment. The old system with high tax rates has been replaced by a new system where companies can choose either a 6 percent tax on gross revenue or a 15 percent tax on profits.[138] Overall tax burden is lower in Russia than in most European countries.[140]

Before the Putin era, in 1998, over 60% of industrial turnover in Russia was based on barter and various monetary surrogates. The use of such alternatives to money now fallen out of favour, which has boosted economic productivity significantly. Besides raising wages and consumption, Putin's government has received broad praise also for eliminating this problem.[141]

The flow of petrodollars was the foundation of Putin's regime and masked economic woes. The share of oil and gas in Russia's gross domestic product has more than doubled since 1999 and as of Q2 2008 stood at above 30%. Oil and gas account for 50% of Russian budget revenues and 65% of its exports.[4]

Some oil revenue went to stabilization fund established in 2004. The fund accumulated oil revenue, which allowed Russia to repay all of the Soviet Union's debts by 2005. In early 2008, it was split into the Reserve Fund (designed to protect Russia from possible global financial shocks) and the National Welfare Fund, whose revenues will be used for a pension reform.[9]

Inflation remained a problem however, as the government failed to contain the growth of prices. Between 1999–2007 inflation was kept at the forecast ceiling only twice, and in 2007 the inflation exceeded that of 2006, continuing an upward trend at the beginning of 2008.[9] The Russian economy is still commodity-driven despite its growth. Payments from the fuel and energy sector in the form of customs duties and taxes accounted for nearly half of the federal budget's revenues. The large majority of Russia's exports are made up by raw materials and fertilizers,[9] although exports as a whole accounted for only 8.7% of the GDP in 2007, compared to 20% in 2000.[142] There is also a growing gap between rich and poor in Russia. Between 2000–2007 the incomes of the rich grew from approximately 14 times to 17 times larger than the incomes of the poor. The income differentiation ratio shows that the 10% of Russia's rich live increasingly better than the 10% of the poor, amongst whom are mostly pensioners and unskilled workers in depressive regions (see Gini coefficient).

[edit] Environmental record

In 2004 President Putin signed the Kyoto Protocol treaty designed to reduce green house gasses. [143] Although, because the Kyoto Protocol limits emissions to a percentage increase or decrease from their 1990 levels Russia did not face mandatory cuts since its greenhouse-gas emissions fell well below the 1990 baseline due to a drop in economic output after the breakup of the Soviet Union.[144]

Recently during the past election Putin and his assumed successor have been talking about the need for Russia to crack down on polluting companies and clean up Russia’s environment. He has been quoted as saying “Working to protect nature must become the systematic, daily obligation of state authorities at all levels.” Mr Medvedev, the man Mr. Putin is supporting to win the presidential poll and succeed him, has also been quoted as saying "There is not much they fear because the penalty for environmental damage is frequently 10 times, even 100 times less than the fees to meet environmental requirements." [145][dated info]

[edit] Foreign policy

| This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. |

In international affairs, Putin has been publicly increasingly critical of the foreign policies of the US and other Western countries. Some[who?] commentators have linked this increase in hostility towards the West with the global rise in oil prices. [146] In February 2007, at the annual Munich Conference on Security Policy, he criticized what he calls the United States' monopolistic dominance in global relations, and pointed out that the United States displayed an "almost uncontained hyper use of force in international relations". He said the result of it is that "no one feels safe! Because no one can feel that international law is like a stone wall that will protect them. Of course such a policy stimulates an arms race."[147]

He called for a "fair and democratic world order that would ensure security and prosperity not only for a select few, but for all". He proposed certain initiatives such as establishing international centres for the enrichment of uranium and prevention of deploying weapons in outer space.[147] In his January 2007 interview Putin said Russia is in favor of a democratic multipolar world and of strengthening the systems of international law.[148]

While Putin is often characterised as an autocrat by the Western media and some[who?] politicians,[149][150] his relationship with former American President George W. Bush, former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, former French President Jacques Chirac, and Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi are reported to be personally friendly. Putin's relationship with Germany's new Chancellor, Angela Merkel, was reported to be "cooler" and "more business-like" than his partnership with Gerhard Schröder. This observation is often attributed to the fact that Merkel was raised in the former DDR, the country of station of Putin when he was a KGB agent.[151]

In the wake of the September 11 attacks on the United States, he agreed to the establishment of coalition military bases in Central Asia before and during the US-led invasion of Afghanistan. Russian nationalists objected to the establishment of any US military presence on the territory of the former Soviet Union, and had expected Putin to keep the US out of the Central Asian republics, or at the very least extract a commitment from Washington to withdraw from these bases as soon as the immediate military necessity had passed.

During the Iraq crisis of 2003, Putin opposed Washington's move to invade Iraq without the benefit of a United Nations Security Council resolution explicitly authorizing the use of military force. After the official end of the war was announced, American president George W. Bush asked the United Nations to lift sanctions on Iraq. Putin supported lifting of the sanctions in due course, arguing that the UN commission first be given a chance to complete its work on the search for weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

In 2005, Putin and former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder negotiated the construction of a major gas pipeline over the Baltic exclusively between Russia and Germany. Schröder also attended Putin's 53rd birthday in Saint Petersburg the same year.

The CIS, seen in Moscow as its traditional sphere of influence, became one of the foreign policy priorities under Putin, as the EU and NATO have grown to encompass much of Central Europe and, more recently, the Baltic states.

During the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, Putin twice visited Ukraine before the election to show his support for Ukrainian Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych, who was widely seen as a pro-Kremlin candidate, and he congratulated him on his anticipated victory before the official election returns had been announced. Putin's personal support for Yanukovych was criticised as unwarranted interference in the affairs of a sovereign state. Crises also developed in Russia's relations with Georgia and Moldova, both former Soviet republics who accused Moscow of supporting separatist entities in their territories. John McCain views Moscow's policies under Putin towards these states to be attempts to bully them.[152]

Putin took an active personal part in promoting the Act of Canonical Communion with the Moscow Patriarchate signed 17 May 2007 that restored relations between the Moscow-based Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia after the 80-year schism.[153]

In his annual address to the Federal Assembly on 26 April 2007, Putin announced plans to declare a moratorium on the observance of the CFE Treaty by Russia until all NATO members ratified it and started observing its provisions, as Russia had been doing on a unilateral basis. Putin argues that as new NATO members have not even signed the treaty so far, an imbalance in the presence of NATO and Russian armed forces in Europe creates a real threat and an unpredictable situation for Russia.[154] NATO members said they would refuse to ratify the treaty until Russia complied with its 1999 commitments made in Istanbul whereby Russia should remove troops and military equipment from Moldova and Georgia. The Russian Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, was quoted as saying in response that "Russia has long since fulfilled all its Istanbul obligations relevant to CFE".[155] Russia suspended its participation in the CFE as of midnight Moscow time on 11 December 2007.[156][157] On 12 December 2007, the United States officially said it "deeply regretted the Russian Federation's decision to 'suspend' implementation of its obligations under the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE)." State Department spokesman Sean McCormack, in a written statement, claimed that "Russia's conventional forces are the largest on the European continent, and its unilateral action damages this successful arms control regime."[158] NATO's primary concern arising from Russia's suspension was that Moscow could accelerate its military presence in the North Caucasus.[159]

The months following Putin's Munich speech[147] were marked by tension and a surge in rhetoric on both sides of the Atlantic. So, Vladimir Putin said at the anniversary of the Victory Day, "these threats are not becoming fewer but are only transforming and changing their appearance. These new threats, just as under the Third Reich, show the same contempt for human life and the same aspiration to establish an exclusive dictate over the world."[160] This was interpreted by some[who?] Russian and Western commentators as comparing the U.S. to Nazi Germany.[citation needed] On the eve of the 33rd Summit of the G8 in Heiligendamm, Anne Applebaum opined that "Whether by waging cyberwarfare on Estonia, threatening the gas supplies of Lithuania, or boycotting Georgian wine and Polish meat, he [Putin] has, over the past few years, made it clear that he intends to reassert Russian influence in the former communist states of Europe, whether those states want Russian influence or not. At the same time, he has also made it clear that he no longer sees Western nations as mere benign trading partners, but rather as Cold War-style threats."[161]

Max Hastings opined that a scenario of military confrontation reminiscent of the Cold War was unlikely, he stated his belief that warm ties between Russia and the West was untenable notion.[162] Both Russian and American officials always denied the idea of a new Cold War. The US defence secretary Robert Gates said on the Munich Conference: "We all face many common problems and challenges that must be addressed in partnership with other countries, including Russia. ... One Cold War was quite enough."[163] Vladimir Putin said prior to 33rd G8 Summit, on 4 June: "we do not want confrontation; we want to engage in dialogue. However, we want a dialogue that acknowledges the equality of both parties’ interests."[108]

Putin publicly opposed plans for the U.S. missile shield in Europe, and presented President George W. Bush with a counterproposal on 7 June 2007 of modernising and sharing the use of the Soviet-era Gabala radar station in Azerbaijan rather than building a new system in the Czech Republic. Putin proposed it would not be necessary to place interceptor missiles in Poland then, but interceptors could be placed in NATO member Turkey or Iraq. Putin suggested also equal involvement of interested European countries in the project.[164]

In a 4 June 2007, interview to journalists of G8 countries, when answering the question of whether Russian nuclear forces may be focused on European targets in case "the United States continues building a strategic shield in Poland and the Czech Republic", Putin admitted that "if part of the United States’ nuclear capability is situated in Europe and that our military experts consider that they represent a potential threat then we will have to take appropriate retaliatory steps. What steps? Of course we must have new targets in Europe."[108][165][166]

The end of 2006 brought strained relations between Russia and the United Kingdom in the wake of the death by poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko in London. On 20 July 2007 UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown expelled four Russian envoys over Russia's refusal to extradite Andrei Lugovoi to face charges on the alleged murder of Litvinenko.[167] The Russian constitution prohibits the extradition of Russian nationals to third countries. British Foreign Secretary David Miliband said that "this situation is not unique, and other countries have amended their constitutions, for example to give effect to the European Arrest Warrant".[168]

Miliband's statement was widely publicized by Russian media as a British proposal to change the Russian constitution.[169][170][171] According to VCIOM, 62% of Russians are against changing the Constitution in this respect.[172] The British Ambassador in Moscow Tony Brenton said that the UK is not asking Russia to break its Constitution, but rather interpret it in such a way that would make Lugovoi's extradition possible.[173] At a meeting with Russian youth organisations, he stated that the United Kingdom was acting like a colonial power with a mindset stuck in the 19th or 20th centuries, due to their belief that Russia could change its constitution. He also stated, "They say we should change our Constitution – advice that I view as insulting for our country and our people. They need to change their thinking and not tell us to change our Constitution."[174][175]

When Litvinenko was dying from radiation poisoning, he allegedly accused Putin of directing the assassination in a statement which was released shortly after his death by his friend Alex Goldfarb.[176] Goldfarb, who is also the chairman of Boris Berezovsky's International Foundation for Civil Liberties, claimed Litvinenko had dictated it to him three days earlier. Andrei Nekrasov said his friend Litvinenko and Litvinenko's lawyer composed the statement in Russian on 21 November and translated it to English.[177] Critics have doubted that Litvinenko is the true author of the released statement.[178][179][180] When asked about the Litvinenko accusations, Putin said that a statement released after death of its author "naturally deserves no comment", and stated his belief it was being used for political purposes.[181][182] Contradicting his previous claim, Goldfarb later stated that Litvinenko instructed him to write a note "in good English" in which Putin was to be accused of his poisoning. Goldfarb also stated that he read the note to Litvinenko in English and Russian, to which he claims Litvinenko agreed "with every word of it" and signed it.[183]

The expulsions were seen as "the biggest rift since the countries expelled each other's diplomats in 1996 after a spying dispute." In response to the situation, Putin stated "I think we will overcome this mini-crisis. Russian-British relations will develop normally. On both the Russian side and the British side, we are interested in the development of those relations." Despite this, British Ambassador Tony Brenton was told by the Russian Foreign Ministry that UK diplomats would be given 10 days before they were expelled in response. The Russian government also announced that it would suspend issuing visas to UK officials and froze cooperation on counterterrorism in response to Britain suspending contacts with their Federal Security Service.[167]

Alexander Shokhin, president of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs warned that British investors in Russia will "face greater scrutiny from tax and regulatory authorities. [And] They could also lose out in government tenders". Some see the crisis as originating with Britain's decision to grant Putin's former patron, Russian billionaire Boris Berezovsky, political asylum in 2003. Earlier in 2007, Berezovsky had called for the overthrow of Putin.[167]

On 10 December 2007, Russia ordered the British Council to halt work at its regional offices in what was seen as the latest round of a dispute over the murder of Alexander Litvinenko; Britain said Russia's move was illegal.[184]

Following the Peace Mission 2007 military exercises jointly conducted by the SCO member states, Putin announced on 17 August 2007 the resumption on a permanent basis of long-distance patrol flights of Russia's strategic bombers that were suspended in 1992.[185][186] US State Department spokesman Sean McCormack was quoted as saying in response that "if Russia feels as though they want to take some of these old aircraft out of mothballs and get them flying again, that's their decision."[186] The announcement made during the SCO summit in the light of joint Russian-Chinese military exercises, first-ever in history to be held on Russian territory,[187] makes some believe that Putin is inclined to set up an anti-NATO bloc or the Asian version of OPEC.[188] When presented with the suggestion that "Western observers are already likening the SCO to a military organisation that would stand in opposition to NATO", Putin answered that "this kind of comparison is inappropriate in both form and substance".[185] Russian Chief of the General Staff Yury Baluyevsky was quoted as saying that "there should be no talk of creating a military or political alliance or union of any kind, because this would contradict the founding principles of SCO".[187]

The resumption of long-distance flights of Russia's strategic bombers was followed by the announcement by Russian Defense Minister Anatoliy Serdyukov during his meeting with Putin on 5 December 2007, that 11 ships, including the aircraft carrier Kuznetsov, would take part in the first major navy sortie into the Mediterranean since Soviet times.[189] The sortie was to be backed up by 47 aircraft, including strategic bombers.[190] According to Serdyukov, this is an effort to resume regular Russian naval patrols on the world's oceans,[191] the view that is also supported by Russian media.[192]

In September 2007, Putin visited Indonesia and in doing so became the first Russian leader to visit the country in more than 50 years.[193] In the same month, Putin also attended the APEC meeting held in Sydney, Australia where he met with Australian Prime Minister John Howard and signed a uranium trade deal. This was the first visit by a Russian president to Australia.

On 16 October 2007 Putin visited Iran to participate in the Second Caspian Summit in Tehran,[194][195] where he met with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad[196]. Other participants were leaders of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan.[197] This is the first visit of a Soviet or Russian leader to Iran since Joseph Stalin's participation in the Tehran Conference in 1943.[198] At a press conference after the summit Putin said that "all our (Caspian) states have the right to develop their peaceful nuclear programmes without any restrictions".[199] During the summit it was also agreed that its participants, under no circumstances, would let any third-party state use their territory as a base for aggression or military action against any other participant.[194]

On 26 October 2007, at a press conference following the 20th Russia–EU Summit in Portugal, Putin proposed creating a Russian-European Institute for Freedom and Democracy headquartered either in Brussels or in one of the European capitals, and added that "we are ready to supply funds for financing it, just as Europe covers the costs of projects in Russia".[200] This newly proposed institution is expected to monitor human rights violations in Europe and contribute to development of European democracy.[201]

Vladimir Putin strongly opposes the secession of Kosovo from Serbia. He called any support for this act "immoral" and "illegal".[202] He described Kosovo's declaration of independence a "terrible precedent" that will come back to hit the West "in the face".[203] He stated that the Kosovo precedent will de facto destroy the whole system of international relations, developed not over decades, but over centuries.[204]

Robert Kagan, reflecting on what underlay the fundamental rift between Putin's Russia and the EU wrote in February 2008: " Europe's nightmares are the 1930s; Russia's nightmares are the 1990s. Europe sees the answer to its problems in transcending the nation-state and power. For Russians, the solution is in restoring them. So what happens when a 21st-century entity faces the challenge of a 19th-century power? The contours of the conflict are already emerging—in diplomatic stand-offs over Kosovo, Ukraine, Georgia and Estonia; in conflicts over gas and oil pipelines; in nasty diplomatic exchanges between Russia and Britain; and in a return to Russian military exercises of a kind not seen since the Cold War. Europeans are apprehensive, with good reason."[205]

Talks on a new Partnership and Co-operation Agreement (PCA), signed in 1997, remained stymied till the end of Putin's presidency due to vetos by Poland and later Lithuania.[206]

A January 2009 dispute led state-controlled Russian company Gazprom to halt its deliveries of natural gas to Ukraine.[207] During the crisis, Putin hinted that Ukraine is run by criminals who cannot solve economic problems.[208]

[edit] Support and popularity

According to public opinion surveys conducted by Levada Center, Putin's approval rating was 81% in June 2007, and the highest of any leader in the world.[209] His popularity rose from 31% in August 1999 to 80% in November 1999 and since then it has never fallen below 65%.[210] Observers see Putin's high approval ratings as a consequence of the significant improvements in living standards and Russia's reassertion of itself on the world scene that occurred during his tenure as President.[211][212][213] Most Russians are also deeply disillusioned with the West after all the hardships of 90s,[214][215] and they no longer trust pro-western politicians associated with Yeltsin that were removed from the political scene under Putin's leadership.[215]

In early 2005, a youth organization called Nashi (meaning 'Ours' or 'Our Own People') was created in Russia, which positions itself as a democratic, anti-fascist organization. Its creation was encouraged by some of the most senior figures in the Administration of the President,[216] and by 2007 it grew to some 120,000 members (between the ages of 17 and 25). One of Nashi's major stated aims was to prevent a repeat of the 2004 Orange Revolution during the Russian elections: as its leader Vasily Yakemenko said, "the enemies must not perform unconstitutional takeovers".[217] Kremlin adviser, Sergei Markov said about the activists of Nashi: "They want Russia to be a modern, strong and free country... Their ideology is clear — it is modernization of the country and preservation of its sovereignty with that."[218]

A joint poll by World Public Opinion in the U. S. and NGO Levada Center [2] in Russia around June–July 2006 stated that "neither the Russian nor the American publics are convinced Russia is headed in an anti-democratic direction" and "Russians generally support Putin’s concentration of political power and strongly support the re-nationalization of Russia’s oil and gas industry." Russians generally support the political course of Putin and his team.[219] A 2005 survey showed that three times as many Russians felt the country was "more democratic" under Putin than it was during the Yeltsin or Gorbachev years, and the same proportion thought human rights were better under Putin than Yeltsin.[220].

Putin was Time Magazine's Person of the Year for 2007[221][222], given the title for his "extraordinary feat of leadership in taking a country that was in chaos and bringing it stability".[223] Time said that "TIME's Person of the Year is not and never has been an honor. It is not an endorsement. It is not a popularity contest. At its best, it is a clear-eyed recognition of the world as it is and of the most powerful individuals and forces shaping that world—for better or for worse". The choice provoked sarcasm from one of Russia's opposition leaders, Garry Kasparov,[224] who recalled that Adolf Hitler had been Time's Man of the Year in 1938 and an overwhelmingly negative reaction from the magazine's readership.[225]

On 4 December 2007, at Harvard University, Mikhail Gorbachev credited Putin with having "pulled Russia out of chaos" and said he was "assured a place in history", "despite Gorbachev's acknowledgment that the news media have been suppressed and that election rules run counter to the democratic ideals he has promoted".[226]

In August 2007, photographs of Putin were taken while he was vacationing in the Siberian mountains. The Russian tabloid Komsomolskaya Pravda published a huge colour photo of the bare-chested president under the headline: "Be Like Putin."[227]

Putin's name and image are widely used in advertisement and product branding. Among the Putin-branded products are Putinka vodka, PuTin brand of canned food, caviar Gorbusha Putina, Denis Simachev's collection of T-shirts decorated by images of Putin, etc.[228]

[edit] Criticism

Despite widespread public support in Russia, Putin has also been the target of much criticism. Several reforms made under Putin’s presidency have been criticized by some independent Russian media outlets and many Western commentators as anti-democratic.[229][230][231].

In 2006 and 2007, "Dissenters' Marches" were organized by the opposition group Other Russia,[232] led by former chess champion Garry Kasparov and national-Bolshevist leader Eduard Limonov. Following prior warnings, demonstrations in several Russian cities were met by police action, which included interfering with the travel of the protesters and the arrests of as many as 150 people who attempted to break through police lines.[233][234] The Dissenters' Marches have received little support among the Russian general public, according to popular polls. [235] The Dissenters' March in Samara held in May 2007 during the Russia-EU summit attracted more journalists providing coverage of the event than actual participants.[236] When asked in what way the Dissenters' Marches bother him, Putin answered that such marches "shall not prevent other citizens from living a normal life".[237] During the Dissenters' March in Saint Petersburg on 3 March 2007, the protesters blocked automobile traffic on Nevsky Prospect, the central street of the city, much to the disturbance of local drivers.[238][239] The Governor of Saint Petersburg, Valentina Matvienko, commented on the event that "it is important to give everyone the opportunity to criticize the authorities, but this should be done in a civilized fashion".[239] When asked about Kasparov's arrest, Putin replied that during his arrest Kasparov was speaking English rather than Russian, and suggested that he was targeting a Western audience rather than his own people.[240][241] Putin has said that some domestic critics are being funded and supported by foreign enemies who would prefer to see a weak Russia.[242] In his speech at the United Russia meeting in Luzhniki: "Those who oppose us don't want us to realize our plan.... They need a weak, sick state! They need a disorganized and disoriented society, a divided society, so that they can do their deeds behind its back and eat cake on our tab."[243].

In July 2007, Bret Stephens of The Wall Street Journal wrote: "Russia has become, in the precise sense of the word, a fascist state. It does not matter here, as the Kremlin's apologists are so fond of pointing out, that Mr. Putin is wildly popular in Russia: Popularity is what competent despots get when they destroy independent media, stoke nationalistic fervor with military buildups and the cunning exploitation of the Church, and ride a wave of petrodollars to pay off the civil service and balance their budgets. Nor does it matter that Mr. Putin hasn't re-nationalized the "means of production" outright; corporatism was at the heart of Hitler's economic policy, too." [244]

In its January 2008 World Report, Human Rights Watch wrote in the section devoted to Russia: "As parliamentary and presidential elections in late 2007 and early 2008 approached, the administration headed by President Vladimir Putin cracked down on civil society and freedom of assembly. Reconstruction in Chechnya did not mask grave human rights abuses including torture, abductions, and unlawful detentions. International criticism of Russia’s human rights record remains muted, with the European Union failing to challenge Russia on its human rights record in a consistent and sustained manner."[245] The organization called President Putin a "repressive" and "brutal" leader on par with the leaders of Zimbabwe and Pakistan.[246]

On 28 January 2008, Gorbachev in his interview to Interfax[247] "sharply criticized the state of Russia’s electoral system and called for extensive reforms to a system that has secured power for President Vladimir V. Putin and the Kremlin’s inner circle."[248] Following Gorbachev's interview The Washington Post's editorial said: "No wonder that Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union's last leader, felt moved to speak out. "Something wrong is going on with our elections", he told the Interfax agency. But it's not only elections: In fact, the system that Mr. Gorbachev took apart is being meticulously reconstructed."[249]

In April 2008, Putin was put on the Time 100 most influential people in the world list.[250] Madeleine Albright wrote: "After our first meetings, in 1999 and 2000, I described him in my journal as "shrewd, confident, hard-working, patriotic, and ingratiating." In the years since, he has become more confident and — to Westerners — decidedly less ingratiating." She added "It is unlikely that Putin, 55, will wear out his welcome at home anytime soon, as he has nearly done with many democracies abroad. In the meantime, he will remain an irritant to NATO, a source of division within Europe and yet another reason for the West to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels."

[edit] Prime Ministry (2008–present)

Vladimir Putin was appointed Prime Minister of Russia on May 8, 2008.

On July 24-25, 2008, Putin accused the Mechel company of selling resources to Russia at higher prices than those charged to foreign countries and claimed that it had been avoiding taxes by using foreign subsidiaries to sell its products internationally. The Prime Minister's attack on Mechel resulted in sharp decline of its stock value and contributed to the 2008 Russian financial crisis.[251][252][253][254]

In August 2008 Putin accused the US of provoking the 2008 South Ossetia war, arguing that US citizens were present in the area of the conflict following their leaders' orders to the benefit of one of the two presidential candidates. [255].

In December 2008, car owners and traders from Vladivostok and other regions protested against highly unpopular new duties and regulations on the import of foreign-made used cars (the tariff hike was introduced by Putin in violation of the international commitments undertaken by Medvedev at the G20 Summit in November 2008[256]), one of the slogans being "Putin, resign!"[257] This was seen as the first visible public anger at one of the government's responses to the crisis.[258] The following month, the protests continued, with the slogans having become of a mostly political nature.[259]

On February 5, 2009, Russia's liberal democratic political movement, citing the regime's "total helplessness and flagrant incompetence"[260][261] maintained that "the dismantling of Putinism" and restoration of democracy in Russia were prerequisites for any successful anti-crisis measures and demanded that Putin's government resign.[260][261][262][263] The Russian governments anti-crisis measures have been praised by the World Bank, which said in its Russia Economic Report from November 2008: "prudent fiscal management and substantial financial reserves have protected Russia from deeper consequences of this external shock. The government’s policy response so far—swift, comprehensive, and coordinated—has helped limit the impact."[264]

[edit] Family and personal life

On 28 July 1983 Putin married Kaliningrad-born Lyudmila Shkrebneva, at that time an undergraduate student of the Spanish branch of the Philology Department of the Leningrad State University and a former Aeroflot flight attendant. They have two daughters, Maria Putina (born 1985 in St. Petersburg) and Yekaterina Putina (born 1986 in Dresden). The daughters grew up in East Germany[265] and attended the German School in Moscow until his appointment as Prime Minister. Putin also owns a black Labrador Retriever named Koni, who has been known to accompany him into staff meetings and greeting world leaders.

Since 1992, Putin has owned a dacha on the eastern shore of the Komsomolskoye Lake in Solovyovka, Priozersky District in Leningrad Oblast. On 10 November 1996, Putin and his neighbours instituted the cooperative Ozero which united their properties. This was confirmed by Putin's income and property declaration as a nominee for the Presidency in 2000.[266] However, this real estate was not listed in his income and property declaration for 1998–2002 submitted before the 2004 elections.[267]

Putin's father was "a model communist, genuinely believing in its ideals while trying to put them into practice in his own life." With this dedication he became secretary of the Party cell in his workshop and then after taking night classes joined the factory’s Party bureau.[268] Though his father was a "militant atheist",[269] Putin's mother "was a devoted Orthodox believer". Though she kept no icons at home, she attended church regularly, despite the government's persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church at that time. She ensured that Putin was secretly christened as a baby and she regularly took him to services. His father knew of this but turned a blind eye.[270] According to Putin's own statements, his religious awakening followed the serious car crash of his wife in 1993, and was deepened by a life-threatening fire that burned down their dacha in August 1996.[269][271] Right before an official visit to Israel his mother gave him his baptismal cross telling him to get it blessed “I did as she said and then put the cross around my neck. I have never taken it off since.”[272] Putin repeated the story to George W. Bush in June 2001, which might have inspired Bush to make his much-derided[273] remark that he had "got a sense of Putin's soul".[274][275] When asked whether he believes in God during his interview with Time, he responded saying: "... There are things I believe, which should not in my position, at least, be shared with the public at large for everybody's consumption because that would look like self-advertising or a political striptease."[276]

Putin speaks German with near-native fluency. His family used to speak German at home as well.[277] After becoming President he was reported to be taking English lessons and could be seen conversing directly with Bush and other native speakers of English in informal situations, but he continues to use interpreters for formal talks. Putin spoke English in public for the first time during the state dinner in Buckingham Palace in 2003 saying but a few phrases while delivering his condolences to the Queen.[278] He made a full English speech while addressing delegates at the 119th International Olympic Committee Session in Guatemala City on behalf of the successful bid of Sochi for the 2014 Winter Olympics.[279]

[edit] Personal wealth

According to the official data submitted during the Russian legislative election, 2007, Putin's wealth is limited to approximately 3.7 million rubles (approximately $150,000) in bank accounts, a private 77.4 square meter apartment in Saint Petersburg, 260 shares of Bank Saint Petersburg (with a December 2007 market price $5.36 per share [3]) and two 1960s Volga M21 cars that he inherited from his father and does not register for on-road use. Putin's 2006 income totalled 2 million rubles (approximately $80,000).[280] According to official data Putin did not make it into the top 100 most wealthy Duma candidates of his own United Russia party.[281]

On the other hand, there have been allegations that Putin secretly owns a large fortune. According to former Chairman of the Russian State Duma Ivan Rybkin[282][283], and Russian political scientist Stanislav Belkovsky[284][285], Putin controls a 4.5% stake (approx. $13 billion) in Gazprom, 37% (approx. $20 billion) in Surgutneftegaz and 50% in the oil-trading company Gunvor run by Gennady Timchenko, a close friend. Gunvor's turnover in 2007 was $40 billion.[34][286][287]. The aggregate estimated value of these holdings would easily make Putin Russia's richest person. In December 2007, Belkovsky elaborated on his claims: "Putin's name doesn't appear on any shareholders' register, of course. There is a non-transparent scheme of successive ownership of offshore companies and funds. The final point is in Zug Switzerland and Liechtenstein. Vladimir Putin should be the beneficiary owner."[75] This claim, however, has never been supported with evidence.[6]

When asked at a press conference on 14 February 2008 whether he was the richest person in Europe, as some newspapers claimed; and if so, to state the source of his wealth, Putin said "This is true. I am the richest person not only in Europe, but also in the world. I collect emotions. And I am rich in that respect that the people of Russia have twice entrusted me with leadership of such a great country as Russia. I consider this to be my biggest fortune. As for the rumors concerning my financial wealth, I have seen some pieces of paper regarding this. This is plain chatter, not worthy discussion, plain bosh. They have picked this in their noses and have smeared this across their pieces of paper. This is how I view this."[288]

[edit] Martial arts

One of Putin's favorite sports is the martial art of judo. Putin began training in sambo (a martial art that originated in the Soviet Union) at the age of 14, before switching to judo, which he continues to practice today.[289] Putin won competitions in his hometown of Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), including the senior championship of Leningrad. He is the President of the Yawara Dojo, the same Saint Petersburg dojo he practiced at when young. Putin co-authored a book on his favorite sport, published in Russian as Judo with Vladimir Putin and in English under the title Judo: History, Theory, Practice.[290]

Though he is not the first world leader to practice judo, Putin is the first leader to move forward into the advanced levels. Currently, Putin holds a 6th dan (red/white belt) and is best known for his Harai Goshi (sweeping hip throw). Putin earned Master of Sports (Soviet and Russian sport title) in Judo in 1975 and in Sambo in 1973. After a state visit to Japan, Putin was invited to the Kodokan Institute where he showed the students and Japanese officials different judo techniques.[291]

[edit] Honors

- On 12 February 2007 Saudi King Abdullah awarded Putin the King Abdul Aziz Award, Saudi Arabia's top civilian decoration.[292]

- On 10 September 2007 UAE President Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan awarded Putin the Order of Zayed, UAE's top civilian decoration.[293]

- In December 2007 Putin was named Person of the Year by Expert magazine, influential and respected Russian business weekly.[294]

- Co-wrote the 1980s pop song 'Neutron Dance' as performed by the Pointer Sisters. He also briefly toured with them as a fill-in drummer during his years working undercover for the KGB.

- Won a bronze in the 1976 Olympic Games for gymnastics.

- In September 2006, France's president Jacques Chirac awarded Vladimir Putin the insignia of Grand-Croix (Grand Cross) of the Légion d'honneur, the highest French decoration, to celebrate his contribution to the friendship between the two countries. This decoration is usually awarded to the heads of state considered very close to France.[295]

[edit] Key speeches

During his terms in office Putin has made[296] eight annual addresses to the Federal Assembly of Russia, speaking on the situation in Russia and on guidelines of the internal and foreign policy of the State (as prescribed in [297] Article 84 of the Constitution). The 2007 election campaign of the United Russia party went under the slogan "Putin's Plan: Russia's Victory". When asked on the "Putin's plan", Vladimir Putin said the last five Addresses contained some key parts "devoted to the state’s medium-term development", and "if all these key ideas were put together to build a coherent system, it can become the country's development plan in the medium-term". [298]

[edit] See also

[edit] References and notes

- ^ "Putin agrees to head ruling United Russia party". Moscow: RIA Novosti. 15 April 2008. http://en.rian.ru/world/20080415/105112727.html. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ "Presidents of Russia. Biographies.". Presidential Press and Information Office. http://kremlin.ru/eng/articles/presidents_eng.shtml. Retrieved on 2008-12-07. Archived at WebCite

- ^ (Russian) Polukin, Alexey (10 January 2008). "К нефти легко примазаться". Novaya Gazeta. http://www.novayagazeta.ru/data/2008/01/10.html. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ a b "Trouble in the pipeline". The Economist. 8 May 2008. http://www.economist.com/business/PrinterFriendly.cfm?story_id=11332313. Retrieved on 2008-11-26.

- ^ "The flight from the rouble". The Economist. 20 November 2008. http://www.economist.com/world/europe/displaystory.cfm?story_id=12641926. Retrieved on 2008-11-26.

- ^ a b c d "Russians weigh Putin's protégé". Moscow: Associated Press. 3 May 2008. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/24443419/print/1/displaymode/1098/. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ GDP of Russia from 1992 to 2007 International Monetary Fund Retrieved on 12 May 2008

- ^ Putin’s Eight Years Kommersant Retrieved on 4 May 2008

- ^ a b c d e f g Russia’s economy under Vladimir Putin: achievements and failures RIA Novosti Retrieved on 1 May 2008

- ^ a b Putin’s Economy – Eight Years On Russia Profile, Retrieved on 23 April 2008

- ^ Putin visions new development plans for Russia China Economic Information Service Retrieved on 8 May 2008

- ^ a b The Putin Paradox

- ^ Russia struggles with galloping inflation

- ^ Friends in high places? By Catherine Belton and Neil Buckley, Financial Times, May 15 2008

- ^ Former Russian Spies Are Now Prominent in Business by Andrew Kramer New York Times December 18, 2007.

- ^ Russia's New Oligarchy: For Putin and Friends, a Gusher of Questionable Deals by Anders Aslund December 12, 2007.

- ^ Миллиардер Тимченко, «друг Путина», стал одним из крупнейших в мире продавцов нефти. NEWSru.com Nov 1, 2007.

- ^ Путин остается премьером, чтобы сохранить контроль над бизнес-империей. NEWSru.com Dec 17, 2007.

- ^ За время президентства Путин «заработал» 40 миллиардов долларов?

- ^ Путин под занавес президентства заключил мегасделки по раздаче госактивов "близким людям" NEWSru.com Mat 13, 2008.

- ^ Независимый экспертеый доклад «Путин. Итоги» Experts' report by Boris Nemtsov and Vladimir Milov released in February 2008.

- ^ За четыре года мздоимство в России выросло почти в десять раз (Bribe-taking in Russia has increased by nearly ten times) Финансовые известия July 21, 2005.

- ^ Energy Revenues and Corruption Increase in Russia Voice of America 13 July 2006.

- ^ Чума-2005: коррупция Argumenty i Fakty № 29 (1290) July 2005

- ^ Russia: Bribery Thriving Under Putin, According To New Report Radio Liberty July 22, 2005

- ^ Putin, the Kremlin power struggle and the $40bn fortune The Guardian Dec 21, 2007

- ^ a b First Person. trans. Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. PublicAffairs. 2000. pp. 208. ISBN 9781586480189.

- ^ An excerpt from the book in The K.G.B. Candidate: Three Moscow journalists talk to Russia's new president, by Bernard Gwertzman, May 14, 2000, The New York Times.

- ^ [Sakwa (2008)], p2

- ^ theme: Russian: «Принцип наиболее благоприятствуемой нации»Выпускники за 1975 год. Saint Petersburg State University's website. ("The principle of most favored nation").

- ^ Владимир Путин. От Первого Лица. Chapter 6

- ^ [Sakwa 2008] pp 8-9

- ^ David Hoffman. Putin's Career Rooted in Russia's KGB. The Washington Post 30 January 2000.

- ^ a b Yuri Felshtinsky and Vladimir Pribylovsky The Age of Assassins. The Rise and Rise of Vladimir Putin, Gibson Square Books, London, 2008, ISBN 190-614207-6, page 45.

- ^ Putin set to visit Dresden, the place of his work as a KGB spy, to tend relations with Germany , International Herald Tribune, 9 October 2006

- ^ Kovalev, Vladimir (2004-07-23). "Uproar At Honor For Putin". The Saint Petersburg Times. http://www.hrvc.net/west/12-8-04.html.

- ^ Hoffman, David (2000-01-30). "Putin's Career Rooted in Russia's KGB". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/russiagov/putin.htm.

- ^ J. Michael Waller (2000-03-17). "Russia Reform Monitor No. 755: U.S. Seen Helping Putin's Presidential Campaign; Documents, Ex-Investigators, Link Putin to Saint Petersburg Corruption". American Foreign Policy Council, Washington, D.C.. http://www.afpc.org/rrm/rrm755.htm.

- ^ Boris Berezovsky (2004-02-24). "New Repartition // What is to be done?". Kommersant. http://www.kommersant.com/p398799/r_1/New_Repartition_/.

- ^ Kovalev, Vladimir (2005-07-29). "Putin Should Settle Doubts About His Past Conduct". The Saint Petersburg Times. http://www.sptimes.ru/index.php?action_id=2&story_id=297.