Methylphenidate

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

|

Methylphenidate

|

|

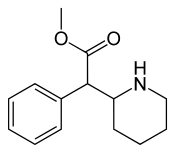

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| methyl phenyl(piperidin-2-yl)acetate | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| ATC code | N06 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C14H19NO2 |

| Mol. mass | 233.31 g/mol |

| SMILES | & |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 11–52% |

| Protein binding | 30% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Half life | 2–4 hours |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. |

C |

| Legal status |

Controlled (S8)(AU) Schedule III(CA) Class B(UK) Schedule II(US) |

| Routes | Oral, Transdermal, IV, Nasal |

Methylphenidate[1] (MPH) is the most commonly prescribed psychostimulant and is indicated in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and narcolepsy, although off-label uses include treating lethargy, depression, neural insult and obesity. In North America it is most commonly known as the brand name Ritalin which is an instant-release racemic mixture, although a variety of brand names, and formulations exist.[2] Methylphenidate is a mild central nervous system stimulant thought to exert its effect by enhancing dopaminergic transmission in the brain.

Contents |

[edit] History

Methylphenidate was patented in 1954 by the CIBA pharmaceutical company (now Novartis) as a potential cure for Mohr's disease.[citation needed] Beginning in the 1960s, it was used to treat children with ADHD or ADD, known at the time as hyperactivity or minimal brain dysfunction (MBD). Today methylphenidate is the most commonly prescribed medication to treat ADHD around the world.[citation needed] Production and prescription of methylphenidate rose significantly in the 1990s, especially in the United States, as the ADHD diagnosis came to be better understood and more generally accepted within the medical and mental health communities.[3]

Most brand-name Ritalin is produced in the United States, and methylphenidate is produced in the United States, Mexico, Argentina and Pakistan. Other generic forms, such as "methylin", are produced by several U.S. pharmaceutical companies. Ritalin is also sold in the United Kingdom, Germany and other European countries (although in much lower volumes than in the United States). These generic versions of methylphenidate tend to outsell brand-name Ritalin four to one.[citation needed] In Belgium the product is sold under the name "Rilatine" and in Portugal as "Ritalina".

Another medicine is Concerta, a once-daily extended-release form of methylphenidate, which was approved in April 2000. Studies have demonstrated that long-acting methylphenidate preparations such as Concerta are just as effective, if not more effective, than IR (instant release) formulas.[4][5][6][7] Time-release medications are also less prone to misuse[citation needed]

In April 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a transdermal patch for the treatment of ADHD called Daytrana.[8]

[edit] Therapeutic uses

Methylphenidate is the most commonly prescribed psychostimulant and works by increasing the activity of the central nervous system.[9] It produces such effects as increasing or maintaining alertness, combating fatigue, and improving attention.[4]

[edit] Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Methylphenidate is approved by the FDA for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder[10] Methylphenidate quickly and effectively reduces the signs and symptoms of ADHD in children under the age of 18.[11]

[edit] Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy, a chronic sleep disorder characterized by overwhelming daytime drowsiness and sudden attacks of sleep, is treated primarily with stimulants. Methylphenidate is considered effective in increasing wakefulness, vigilance, and performance.[12] Methylphenidate improves measures of somnolence on standardized tests, such as the Multiple Sleep Latency Test, but performance does not improve to levels comparable to healthy controls.[13]

[edit] Adjunctive

In individuals with cancer, methylphenidate is commonly used to counteract opioid-induced somnolence, to increase the analgesic effects of opioids, to treat depression, and to improve cognitive function.[14] Methylphenidate may be used in addition to an antidepressant for treatment-refractory major depressive disorder. It can also improve depression in several groups including stroke, cancer, HIV-positive patients.[15]

[edit] Substance dependence

Methylphenidate has been investigated as a chemical replacement for the treatment of cocaine dependence[16] in the same way that methadone is used as a replacement for heroin.

Early research began in 2007-8 in some countries on the effectiveness of methylphenidate as a substitute agent in refractory cases of cocaine dependence; the fact that it can satisfy cravings for cocaine in a way which is subjectively and pharmacologically equivalent but longer-lasting as well as easier on the body and somewhat safer and easier to manage has long been part of the 'street lore' associated with stimulants in many parts of the world in much the same way that other substitutionmittel drugs such as methadone, buprenorphine, butorphanol, extended-release oral morphine, dihydrocodeine, and clonidine were amongst opioid users in various times over the past century.[clarification needed]

[edit] Pervasive developmental disorders

Given the high co-morbidity between ADHD and autism, a few studies have examined the efficacy and effectiveness of methylphenidate in the treatment of autism. However, most of these studies examined the effects of methylphenidate on attention and hyperactivity symptoms among kids with autism spectrum disorders. Aman and Langworthy (2000) attempted to examine the effects of methylphenidate on social-communication and self-regulation behaviors among kids with ASDs.[17]

The sample included 33 children with pervasive developmental disorder (29 boys) with a mean age of 6.93 years (range 5-13). This was a 4-week randomized, double-blind, cross-over placebo study, with treatment changing each week between 4 conditions: placebo, low dose, medium dose, and high dose. In this design, neither the experimenters nor the families know which of the 4 treatments the child is receiving at any given time. In addition, the treatment condition changes randomly each week, without anyone knowing the nature of the old or new condition. This allows the experimenters to assume that consistent changes in behaviors that occur during a particular treatment is truly due to the effect of that treatment and not to the expectation of the treatment (placebo effect).

The results indicate that children showed significantly more joint attention behaviors when receiving methylphenidate than when receiving the placebo (although the most effective dosage varied by individual). Furthermore, at a group level, the low dose of methylphenidate resulted in significantly improved joint attention behaviors when compared to the placebo, but no differences were noted between the low, medium, and high doses. Low and medium doses of methylphenidate also resulted in improved self-regulation behavior when compared to placebo.

The study presents compelling preliminary evidence suggesting that methylphenidate is effective in improving some social behaviors among children with autism spectrum disorders.[18]

[edit] Investigational

Animal studies assessing the safety of methylphenidate on the developing brain found that psychomotor impairments, structural and functional parameters of the dopaminergic system were improved with treatment. This animal data suggests that methylphenidate supports brain development and hyperactivity in children diagnosed with ADHD.[19]

Methylphenidate may reduce the risk of falls in older adults by treating cognitive deficits associated with aging and disease.[20]

[edit] Adverse effects

The most common side effects of taking methylphenidate are nervousness and insomnia. Other reactions include hypersensitivity (including skin rash, urticaria, fever, arthralgia, exfoliative dermatitis, erythema multiforme with histopathological findings of necrotizing vasculitis, and thrombocytopenic purpura); anorexia; nausea; dizziness; palpitations; headache; dyskinesia; drowsiness; blood pressure and pulse changes, both up and down; tachycardia; angina; cardiac arrhythmia; abdominal pain; and weight loss during prolonged therapy. Very rare effects include reports of Tourette's syndrome, toxic psychosis, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. [21]

[edit] Known or suspected risks to health

Researchers have also looked into the role of methylphenidate in affecting stature, with some studies finding slight decreases in height acceleration.[22] Other studies indicate height may normalize by adolescence.[23][24] In a 2005 study, only "minimal effects on growth in height and weight were observed" after 2 years of treatment. "No clinically significant effects on vital signs or laboratory test parameters were observed."[25]

A 2003 study tested the effects of dextromethylphenidate (Focalin), levomethylphenidate, and (racemic) detro-, levomethylphenidate (Ritalin) on mice to search for any carcinogenic effects. The researchers found that all three preparations were non-genotoxic and non-clastogenic; d-MPH, d, l-MPH, and l-MPH did not cause mutations or chromosomal aberrations. They concluded that none of the compounds present a carcinogenic risk to humans.[26] Current scientific evidence supports that long-term methylphenidate treatment does not increase the risk of developing cancer in humans.[27]

The effects of long-term methylphenidate treatment on the developing brains of children with ADHD is the subject of study and debate.[28][29] Although the safety profile of short-term methylphenidate therapy in clinical trials has been well established, repeated use of psychostimulants such as methylphenidate is less clear.

The use of ADHD medication in children under the age of 6 has not been studied. Severe hallucinations may occur. ADHD symptoms include hyperactivity and difficulty holding still and following directions; these are also characteristics of a typical child under the age of 6. For this reason it may be more difficult to diagnose young children, and caution should be used with this age group.[citation needed]

On March 22, 2006 the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee decided that medications using methylphenidate ingredients do not need black box warnings about their risks, noting that "for normal children, these drugs do not appear to pose an obvious cardiovascular risk."[30] Previously, 19 possible cases had been reported of Cardiac arrest linked to children taking methylphenidate[31] and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee to the FDA recommend a "black-box" warning in 2006 for stimulant drugs used to treat attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.[32]

[edit] Contraindications

Methylphenidate should not be prescribed concomitantly with tricyclic antidepressants, such as desipramine, or monoamine oxidase inhibitors, such as phenelzine or tranylcypromine, as methylphenidate may dangerously increase plasma concentrations, leading to potential toxic reactions (mainly, cardiovascular effects). Methylphenidate should not be prescribed to patients who suffer from severe arrhythmia, hypertension or liver damage. It shouldn't be prescribed to patients who demonstrate drug-seeking behaviour, pronounced agitation or nervousness.

[edit] Interactions

When methylphenidate is coingested with ethanol, ethylphenidate is formed via hepatic transesterification.[33] It is more selective to the dopamine transporter (DAT) than methylphenidate, having approximately the same efficacy as the parent compound,[34] but has significantly less activity on the norepinephrine transporter (NET).[35]

[edit] Overdose

In 2004, over 8000 methylphenidate ingestions were reported in US poison center data.[36] The most common reasons for intentional exposure were drug abuse and suicide attempts.[37] An overdose manifests in agitation, hallucinations, psychosis, lethargy, seizures, tachycardia, dysrhythmias, hypertension, and hyperthermia.[38] Benzodiazepines may be used as treatment if agitation, dystonia, or convulsions are present.[36]

[edit] Pharmacokinetics

Methylphenidate has binding affinity for both the dopamine transporter and norepinephrine transporter, with the Dextromethylphenidate enantiomers displaying a prominent affinity for the norepinephrine transporter. Both the dextro- and levorotary enantiomers displayed receptor affinity for the serotonergic 5HT1A and 5HT2B subtypes, though direct binding to the serotonin transporter was not observed.[39]

The enantiomers and the relative psychoactive effects and CNS stimulation of dextro- and levo-methylphenidate is analogous to what is found in amphetamine, where dextro-amphetamine is considered to have a greater psychoactive and CNS stimulatory effect than levo-amphetamine.

[edit] Pharmacodynamics

The means by which methylphenidate affects people diagnosed with ADHD are not well understood. Some researchers have theorized that ADHD is caused by a dopamine imbalance in the brains of those affected. Methylphenidate is a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, which means that it increases the level of the dopamine neurotransmitter in the brain by partially blocking the dopamine transporter (DAT) that removes dopamine from the synapses.[40] This inhibition of DAT blocks the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into the presynaptic neuron, increasing the amount of dopamine in the synapse. It also stimulates the release of dopamine and norepinephrine into the synapse[citation needed]. Finally, it increases the magnitude of dopamine release after a stimulus, increasing the salience of stimulus. An alternate explanation which has been explored is that the methylphenidate affects the action of serotonin in the brain.[41]

It is commonly asked why a stimulant should be used to treat hyperactivity, which seems paradoxical. However, MRIs of ADHD brains show decreased activity in the brain centers critical to concentration and goal-directed activities.[42] Treatment with methylphenidate (etc.) results in increased activity in those regions, in ADHD patients, and in healthy controls as well. Thus the model explanation is that hyperactive children (and adults) have underactive concentration centers, and stimulating them reduces hyperactivity. Thus the stimulants do not work paradoxically. They stimulate portions of the brain that are underactive by increasing dopamine and norepinephrine in the striatum and prefontal cortex.

One study finds that methylphenidate reduces the increases in brain glucose metabolism during performance of a cognitive task by about 50%. This suggests that, similar to increasing dopamine and norepinephrine in the striatum and prefrontal cortex, methylphenidate may focus activation of certain regions and make the brain more efficient. This is consistent with the observation that stimulant drugs can enhance attention and performance in some individuals. If brain resources are not optimally distributed (for example, in individuals with ADHD or sleep deprivation), improved performance could be achieved by reducing task-induced regional activation. Stimulant delivery when brain resources are already optimally distributed may then adversely affect performance.[43]

A paper published in Biological Psychiatry reports that methylphenidate fine-tunes the functioning of neurons in the prefrontal cortex - a brain region involved in attention, decision-making and impulse control - while having few effects outside it. The team studied PFC neurons in rats under a variety of methylphenidate doses, including one that improved the animals' performance in a working memory task of the type that ADHD patients have trouble completing. Using microelectrodes, the scientists observed both the random, spontaneous firings of PFC neurons and their response to stimulation of the hippocampus. When they listened to individual PFC neurons, the scientists found that while cognition-enhancing doses of methylphenidate had little effect on spontaneous activity, the neurons' sensitivity to signals coming from the hippocampus increased dramatically. Under higher, stimulatory doses, on the other hand, PFC neurons stopped responding to incoming information.[44] Another study suggests that methylphenidate improves spatial orientation and working memory in rats on the radial arm maze.

[edit] Scheduling and abuse potential

The primary source for methylphenidate for abuse is diversion from legitimate prescriptions rather than illicit synthesis. Those who use to stay awake do so by taking it orally, while intranasal and intravenous are the preferred means for inducing euphoria.[38] IV users tend to be adults whose use may cause panlobular pulmonary emphysema.[37]

It is generally accepted that methylphenidate is the closest pharmaceutical equivalent to cocaine[citation needed], and studies have shown that the two drugs are nearly indistinguishable when administered intravenously to cocaine addicts.[45]. However, cocaine has a slightly higher affinity for the dopamine receptor in comparison to methylphenidate, which is thought to be the mechanism of the euphoria associated with the relatively short-lived cocaine high.[46]

In the United States, methylphenidate is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance, the designation used for substances that have a recognized medical value but present a high likelihood for abuse because of their addictive potential. Internationally, methylphenidate is a Schedule II drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[47]

[edit] Delivery formulations

All media are in milligrams.

[edit] Tablet

- Ritalin: 5, 10 or 20 mg tablets.

- Ritalin SR: 20 mg controlled-release tablets.

- Attenta: 10 mg tablets.

- Methylin: 5, 10 or 20 mg tablets.

- Methylin ER: 10 and 20 mg controlled-release tablets.

- Metadate ER: 10 and 20 mg controlled-release tablets.

- Equasym: 5, 10, 20 or 30 mg tablets.

- Rubifen: 5, 10 or 20 mg tablets.

[edit] Capsules

- Ritalin LA: 10, 20, 30 or 40 mg controlled-release capsules.

- Metadate CD: 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 or 60 mg controlled-release capsules.

- Biphentin: 10, 15, 30, 40, or 60 mg suspended release capsules.

[edit] Patches

- Daytrana 10, 15, 20 or 30 mg controlled-release patches (1.1, 1.6, 2.2 or 3.3 mg/hour for 9 hours).

[edit] Controversy

Methylphenidate, usually referred to as the brand name Ritalin, has been related to controversy regarding the treatment of ADHD. Criticism generally revolves around alleged or established side effects, concerns of illicit use and abuse, and the ethics of giving psychotropic drugs to children to reduce ADHD symptoms.[50] In 2002, a study showed that rats treated with methylphenidate are more receptive to the reinforcing effects of cocaine,[46] which seeded doubts if the medication is a gateway drug to substance abuse. However, this contention has since been discredited by multiple sources.[51][52]

According to an article in the Los Angeles Times, "the uproar over Ritalin was triggered almost single-handedly by the Scientology movement."[53] The Citizens Commission on Human Rights, an antipsychiatry group associated with Scientology, conducted a major campaign against Ritalin in the 1980s and lobbied Congress for an investigation of Ritalin.[53]

Richard Bromfield claims that Ritalin is often prescribed not because of an underlying neurological disorder, but as an easy way to calm down children whose misbehavior actually results from ordinary causes such as bad parenting.[54]

[edit] See also

- Ethylphenidate

- O-2172

- Psychoactive drug

- Steroid

- Amphetamine

- Methamphetamine

- Benzedrine

- Controversy about ADHD

- Pemoline

[edit] References

- ^ Pronunciation

- ^ Brand names also include Ritalina, Rilatine, Attenta (in Australia), Methylin, Penid, and Rubifen; and the sustained release tablets Concerta, Metadate CD, Methylin ER, Ritalin LA, and Ritalin-SR. Focalin is a preparation containing only dextro-methylphenidate, rather than the usual racemic dextro- and levo-methylphenidate mixture of other formulations. A newer way of taking methylphenidate is by using a transdermal patch (under the brand name Daytrana), similar to those used for nicotine replacement therapy.

- ^ "News from DEA, Congressional Testimony, 05/16/00". http://www.dea.gov/pubs/cngrtest/ct051600.htm. Retrieved on 2007-11-02.

- ^ a b Steele, M., et al. (2006). "A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of OROS-methylphenidate compared to usual care with immediate-release methylphenidate in Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity DisorderPDF (293 KB)". Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2006 Winter;13(1):e50-62.

- ^ Pelham, W.E., et al. (2001). "Once-a-day Concerta methylphenidate versus three-times-daily methylphenidate in laboratory and natural settings". Pediatrics. 2001 Jun;107(6):E105.

- ^ Keating, G.M., McClellan, K., Jarvis, B. (2001). "Methylphenidate (OROS formulation)". CNS Drugs. 2001;15(6):495-500; discussion 501-3.

- ^ Hoare, P., et al. (2005). "12-month efficacy and safety of OROS methylphenidate in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder switched from MPHPDF". Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Sep;14(6):305-9.

- ^ Peck, P. (2006, 7 April). FDA Approves Daytrana Transdermal Patch for ADHD. MedPage today. Retrieved April 7, 2006, from http://www.medpagetoday.com/ProductAlert/Prescriptions/tb/3027.

- ^ Markowitz JS, Logan BK, Diamond F, Patrick KS (August 1999). "Detection of the novel metabolite ethylphenidate after methylphenidate overdose with alcohol coingestion". J Clin Psychopharmacol 19 (4): 362–6. doi:. PMID 10440465. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0271-0749&volume=19&issue=4&spage=362.

- ^ Fone KC; Nutt DJ. (February 2005). "Stimulants: use and abuse in the treatment of attention deficit disorder.". Current opinion in pharmacology. 5 (1): 87–93. doi:. PMID 15661631.

- ^ Schachter HM, Pham B, King J, Langford S, Moher D (November 2001). "How efficacious and safe is short-acting methylphenidate for the treatment of attention-deficit disorder in children and adolescents? A meta-analysis". CMAJ 165 (11): 1475–88. PMID 11762571. PMC: 81663. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11762571.

- ^ Fry JM (February 1998). "Treatment modalities for narcolepsy". Neurology 50 (2 Suppl 1): S43–8. PMID 9484423.

- ^ Mitler MM (December 1994). "Evaluation of treatment with stimulants in narcolepsy". Sleep 17 (8 Suppl): S103–6. PMID 7701190.

- ^ Rozans M, Dreisbach A, Lertora JJ, Kahn MJ (January 2002). "Palliative uses of methylphenidate in patients with cancer: a review". J. Clin. Oncol. 20 (1): 335–9. doi:. PMID 11773187. http://www.jco.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11773187.

- ^ Leonard BE, McCartan D, White J, King DJ (April 2004). "Methylphenidate: a review of its neuropharmacological, neuropsychological and adverse clinical effects". Hum Psychopharmacol 19 (3): 151–80. doi:. PMID 15079851.

- ^ Grabowski J, Roache JD, Schmitz JM, Rhoades H, Creson D, Korszun A (December 1997). "Replacement medication for cocaine dependence: methylphenidate". J Clin Psychopharmacol 17 (6): 485–8. doi:. PMID 9408812. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0271-0749&volume=17&issue=6&spage=485.

- ^ Aman MG, Langworthy KS (October 2000). "Pharmacotherapy for hyperactivity in children with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders". J Autism Dev Disord 30 (5): 451–9. doi:. PMID 11098883. http://www.kluweronline.com/art.pdf?issn=0162-3257&volume=30&page=451.

- ^ A review of: Laudan B. Jahromi, Connie L. Kasari, James T. McCracken, Lisa S-Y. Lee, Michael G. Aman, Christopher J. McDougle, Lawrence Scahill, Elaine Tierney, L. Eugene Arnold, Benedetto Vitiello, Louise Ritz, Andrea Witwer, Erin Kustan, Jaswinder Ghuman, David J. Posey (2008). Positive Effects of Methylphenidate on Social Communication and Self-Regulation in Children with Pervasive Developmental Disorders and Hyperactivity Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders DOI: 10.1007/s10803-008-0636-9

- ^ Grund T., et al. "Influence of methylphenidate on brain development - an update of recent animal experiments", Behav Brain Funct. 2006 January 10;2:2.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Ritalin & Ritalin-SR Prescribing Information" (PDF). Novartis. April 2007. http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/ritalin_ritalin-sr.pdf.

- ^ Rao J.K., Julius J.R., Breen T.J., Blethen S.L. (1996). "Response to growth hormone in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of methylphenidate and pemoline therapy". Pediatrics. 1998 Aug;102 (2 Pt 3):497-500.

- ^ Spencer, T.J., et al. (1996)."Growth deficits in ADHD children revisited: evidence for disorder-associated growth delays?". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996 Nov;35(11):1460-9.

- ^ Klein R.G. & Mannuzza S. (1988). "Hyperactive boys almost grown up. III. Methylphenidate effects on ultimate height". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988 Dec;45(12):1131-4.

- ^ Wilens, T., et al. (2005). ADHD treatment with once-daily OROS methylphenidate: final results from a long-term open-label study". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Oct;44(10):1015-23.

- ^ Teo, S.K., et al. (2003). "D-Methylphenidate is non-genotoxic in vitro and in vivo assays". Mutat Res. 2003 May 9;537(1):67-79.

- ^ Walitza, Susanne (June 2007). "Does Methylphenidate Cause a Cytogenetic Effect in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder?". Environmental Health Perspectives 115 (6): 936–940. doi:. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1892117.

- ^ ADHD & Women's Health - Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder National Women's Health Report. February 2003. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0NKT/is_1_25/ai_99698688/pg_4. Retrieved on 2007-11-03. "Although methylphenidate is perhaps one of the best-studied drugs available, with thousands of studies attesting to its longterm safety over the past 50 years, that hasn't stopped critics from raising alarms about the drug's long-term use on children's developing brains, particularly given research that finds the numbers of children taking the drug skyrocketing in recent years.".

- ^ Edmund J. S. Sonuga-Barke, Margaret Thompson, Howard Abikoff, Rachel Klein, Laurie Miller Brotman. "Nonpharmacological Interventions for Preschoolers With ADHD: The Case for Specialized Parent Training" (PDF). Infants & Young Children 19 (2): 142–153. http://depts.washington.edu/isei/iyc/sonuga_19.2.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-12-30. "While most recent studies suggest that methylphenidate is relatively well-tolerated by young children, some suggest that side effects might be more marked in preschoolers than in school-aged children (Firestone, Musten, Pisterman, Mercer, & Bennett, 1998). Furthermore, some researchers have argued that there is the potential for negative long-term effects on the developing brains of young children chronically medicated (Moll, Rothenberger, Ruther, & Huther, 2002).".

- ^ Minutes of the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee. March 22, 2006.

- ^ New Scientist 18 February 2006

- ^ Minutes of the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee, March 22, 2006

- ^ Markowitz JS, DeVane CL, Boulton DW, Nahas Z, Risch SC, Diamond F, Patrick KS. Ethylphenidate formation in human subjects after the administration of a single dose of methylphenidate and ethanol. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2000 Jun;28(6):620-4.

- ^ Patrick KS, Williard RL, VanWert AL, Dowd JJ, Oatis JE Jr, Middaugh LD. Synthesis and pharmacology of ethylphenidate enantiomers: the human transesterification metabolite of methylphenidate and ethanol. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2005 Apr 21;48(8):2876-81.

- ^ Williard RL, Middaugh LD, Zhu HJ, Patrick KS. Methylphenidate and its ethanol transesterification metabolite ethylphenidate: brain disposition, monoamine transporters and motor activity. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2007 Feb;18(1):39-51.

- ^ a b Scharman EJ, Erdman AR, Cobaugh DJ, et al (2007). "Methylphenidate poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management". Clin Toxicol (Phila) 45 (7): 737–52. doi:. PMID 18058301.

- ^ a b Stern EJ, Frank MS, Schmutz JF, Glenny RW, Schmidt R, Godwin JD (March 1994). "Panlobular pulmonary emphysema caused by i.v. injection of methylphenidate (Ritalin): findings on chest radiographs and CT scans". AJR Am J Roentgenol 162 (3): 555–60. PMID 8109495. http://www.ajronline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=8109495.

- ^ a b Klein-Schwartz W (April 2002). "Abuse and toxicity of methylphenidate". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 14 (2): 219–23. doi:. PMID 11981294. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=1040-8703&volume=14&issue=2&spage=219.

- ^ Markowitz JS, DeVane CL, Pestreich LK, Patrick KS, Muniz R (December 2006). "A comprehensive in vitro screening of d-, l-, and dl-threo-methylphenidate: an exploratory study". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16 (6): 687–98. doi:. PMID 17201613.

- ^ Volkow N., et al. (1998). "Dopamine Transporter Occupancies in the Human Brain Induced by Therapeutic Doses of Oral Methylphenidate". Am J Psychiatry 155:1325-1331, October 1998.

- ^ Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Caron, Marc G. (March 2001). "Genetics of Childhood Disorders: XXIV. ADHD, Part 8: Hyperdopaminergic Mice as an Animal Model of ADHD". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 40 (3): 380–382. doi:. http://www.med.yale.edu/chldstdy/plomdevelop/genetics/01margen.htm. Retrieved on 2006-11-11.

- ^ Rosack Jim (02 January 2004). "Brain Scans Reveal Physiology of ADHD". Psychiatric News 39 (1): 26. http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/39/1/26.

- ^ Volkow, ND; Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Telang F, Logan J, Wong C, Ma J, Pradhan K, Benveniste H, Swanson JM (April 2008). "Methylphenidate decreased the amount of glucose needed by the brain to perform a cognitive task". PLoS ONE 3 (4): e2017. doi:. PMID 18414677. http://scivee.tv/node/5977. Retrieved on 2008-11-26.

- ^ Devilbiss DM, Berridge CW (October 2008). "Cognition-enhancing doses of methylphenidate preferentially increase prefrontal cortex neuronal responsiveness". Biol. Psychiatry 64 (7): 626–35. doi:. PMID 18585681.

- ^ http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/288/1/14#Introduction "Almost indistinguishable from that [high] induced by i.v. cocaine"

- ^ a b http://www.udel.edu/chemo/teaching/CHEM465/SitesF02/Prop26b/Rit%20Page4.html Pretreatment with methylphenidate sensitizes rats to the reinforcing effects of cocaine

- ^ Green List: Annex to the annual statistical report on psychotropic substances (form P)PDF (1.63 MB) 23rd edition. August 2003. International Narcotics Board, Vienna International Centre. Retrieved 2 March 2006

- ^ Full Prescribing Information for Concerta. (215 KiB)

- ^ Generic Concerta

- ^ Lakhan SE, Hagger-Johnson GE (2007). "The impact of prescribed psychotropics on youth". Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health 3: 21. doi:. PMID 17949504. PMC: 2100041. http://www.cpementalhealth.com/content/3/1/21.

- ^ Wilens, T.E.., et al. (2003). "Does Stimulant Therapy of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Beget Later Substance Abuse? A Meta-analytic Review of the Literature". PEDIATRICS. 2003 Vol. 111 No. 1:pp. 179-185

- ^ Russell A. Barkley, PhD,et al. (2003). "Does the Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder With Stimulants Contribute to Drug Use/Abuse? A 13-Year Prospective Study". PEDIATRICS. 2003 Vol. 111 No. 1: pp. 97-109

- ^ a b Sappell, Joel; Welkos, Robert W. (1990-06-29). "Suits, Protests Fuel a Campaign Against Psychiatry". Los Angeles Times: p. A48:1. http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-scientology062990a,1,6085874,full.story?coll=la-news-comment. Retrieved on 2006-11-29. Backup copy link here

- ^ Richard, Bromfield; Jerry Wiener (July 1, 1996). "The Debate of Ritalin: Point & Counterpoint". Priorities 8 (3). http://www.presidioinc.com/newsletter/99newsarchive/99julyaug_feature.htm. Retrieved on 2009-02-28.

[edit] External links

- Methylphenidate at the Open Directory Project

- Department of Energy 1998 September 29 press release on Ritalin at Brookhaven National Laboratory

- www.Erowid.org Online library of psychoactive plants, chemicals and related topics from Erowid.org

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||