Wall Street Crash of 1929

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Wall Street Crash of 1929,[1][2] also known as the Great Crash, was the most devastating stock market crash in the history of the United States, taking into consideration the full extent and longevity of its fallout.[3]

Three phrases — Black Thursday, Black Monday, and Black Tuesday — are commonly used to describe this collapse of stock values. All three are appropriate, for the crash was not a one-day affair. The initial crash occurred on Thursday, October 24, 1929, but it was the catastrophic downturn of Monday, October 28 and Tuesday, October 29 that precipitated widespread alarm and the onset of an unprecedented and long-lasting economic depression for the United States and the world. The stock market collapse continued for a month.

Economists and historians disagree as to what role the crash played in subsequent economic, social, and political events. In a 1998 article The Economist argued, "Briefly, the Depression did not start with the stockmarket crash."[4] Nor was it clear at the time of the crash that a depression was starting. On November 23, 1929, The Economist asked: "Can a very serious Stock Exchange collapse produce a serious setback to industry when industrial production is for the most part in a healthy and balanced condition? ... Experts are agreed that there must be some setback, but there is not yet sufficient evidence to prove that it will be long or that it need go to the length of producing a general industrial depression." But The Economist cautioned: "Some bank failures, no doubt, are also to be expected. In the circumstances will the banks have any margin left for financing commercial and industrial enterprises or will they not? The position of the banks is without doubt the key to the situation, and what this is going to be cannot be properly assessed until the dust has cleared away."[5]

The October 1929 crash came during a period of declining real estate values in the United States (which peaked in 1925) near the beginning of a chain of events that led to the Great Depression, a period of economic decline in the industrialized nations.

At the time of the unbelievable crash, New York City had grown to be a major metropolis, and its Wall Street district was one of the world's leading financial centers. The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) was the largest stock market in the world.[citation needed]

The Roaring Twenties, the decade leading up to the Crash,[6] was a time of wealth and excess in the city, and despite caution of the dangers of speculation, many believed that the market could sustain high price levels. Shortly before the crash, Irving Fisher famously proclaimed, "Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau."[7] The optimism and financial gains of the great bull market were shattered on Black Thursday, when share prices on the NYSE collapsed. Stock prices fell on that day and they continued to fall, at an unprecedented rate, for a full month.[8]

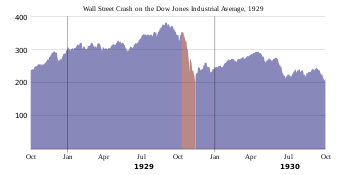

In the days leading up to Black Tuesday, the market was severely unstable. Periods of selling and high volumes of trading were interspersed with brief periods of rising prices and recovery. Economist and author Jude Wanniski later correlated these swings with the prospects for passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which was then being debated in Congress.[9] After the crash, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) recovered early in 1930, only to reverse and crash again, reaching a low point of the great bear market in 1932. On July 8, 1932 the Dow reached its lowest level of the 20th century and did not return to pre-1929 levels until 23 November 1954.[10][11]

| “ | Anyone who bought stocks in mid-1929 and held onto them saw most of his or her adult life pass by before getting back to even. | ” |

Contents |

[edit] Timeline

After a six-year run when the world saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average increase in value fivefold, prices peaked at 381.17 on September 3, 1929.[13] The market then fell sharply for a month, losing 17% of its value on the initial leg down.

Prices then recovered more than half of the losses over the next week, only to turn back down immediately afterwards. The decline then accelerated into the so-called "Black Thursday", October 24, 1929. A record number of 12.9 million shares were traded on that day.

At 1 p.m. on Friday, October 25, several leading Wall Street bankers met to find a solution to the panic and chaos on the trading floor. The meeting included Thomas W. Lamont, acting head of Morgan Bank; Albert Wiggin, head of the Chase National Bank; and Charles E. Mitchell, president of the National City Bank. They chose Richard Whitney, vice president of the Exchange, to act on their behalf. With the bankers' financial resources behind him, Whitney placed a bid to purchase a large block of shares in U.S. Steel at a price well above the current market. As traders watched, Whitney then placed similar bids on other "blue chip" stocks. This tactic was similar to a tactic that ended the Panic of 1907, and succeeded in halting the slide that day. In this case, however, the respite was only temporary.

Over the weekend, the events were covered by the newspapers across the United States. On Monday, October 28, the first "Black Monday",[14] more investors decided to get out of the market, and the slide continued with a record loss in the Dow for the day of 13%. The next day, "Black Tuesday", October 29, 1929, about 16 million shares were traded.[15][16][17] The volume on stocks traded on October 29, 1929 was "...a record that was not broken for nearly 40 years, in 1968."[16] Author Richard M. Salsman wrote that on October 29—amid rumors that U.S. President Herbert Hoover would not veto the pending Hawley-Smoot Tariff bill—stock prices crashed even further."[12] William C. Durant joined with members of the Rockefeller family and other financial giants to buy large quantities of stocks in order to demonstrate to the public their confidence in the market, but their efforts failed to stop the slide. The DJIA lost another 12% that day. The ticker did not stop running until about 7:45 that evening. The market lost $14 billion in value that day, bringing the loss for the week to $30 billion, ten times more than the annual budget of the federal government, far more than the U.S. had spent in all of World War I.[18]

| date | change | % change | close |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 28, 1929 | -38.33 | -12.82 | 260.64 |

| October 29, 1929 | -30.57 | -11.73 | 230.07 |

An interim bottom occurred on November 13, with the Dow closing at 198.60 that day. The market recovered for several months from that point, with the Dow reaching a secondary peak (ie, dead cat bounce) at 294.0 in April 1930. The market embarked on a steady slide in April 1931 that did not end until 1932 when the Dow closed at 41.22 on July 8, concluding a shattering 89% decline from the peak. This was the lowest the stock market had been since the 19th century.[20]

[edit] Economic fundamentals

The crash followed a speculative boom that had taken hold in the late 1920s, which had led hundreds of thousands of Americans to invest heavily in the stock market, a significant number even borrowing money to buy more stock. By August 1929, brokers were routinely lending small investors more than 2/3 of the face value of the stocks they were buying. Over $8.5 billion was out on loan,[21] more than the entire amount of currency circulating in the U.S.[citation needed] The rising share prices encouraged more people to invest; people hoped the share prices would rise further. Speculation thus fueled further rises and created an economic bubble. The average P/E (price to earnings) ratio of S&P Composite stocks was 32.6 in September 1929,[22] clearly above historical norms. Most economists view this event as the most dramatic in modern economic history. On October 24, 1929 (with the Dow just past its September 3 peak of 381.17), the market finally turned down, and panic selling started. 12,894,650 shares were traded in a single day as people desperately tried to mitigate the situation. This mass sale is often considered a major contributing factor to the Great Depression.[23] Some hold that political over-reactions to the crash, such as the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act through the U.S. Congress, caused more harm than the crash itself. According to Thomas K. McCraw, a professor at the Harvard Business School, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act "...exacerbated the problem by preventing Europeans from selling enough goods in the United States to earn enough money to pay off their debts from World War I."[24]

[edit] Official investigation of the Crash

In 1931, the Pecora Commission was established by the U.S. Senate to study the causes of the crash. The U.S. Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933, which mandated a separation between commercial banks, which take deposits and extend loans, and investment banks, which underwrite, issue, and distribute stocks, bonds, and other securities.

After the experience of the 1929 crash, stock markets around the world instituted measures to temporarily suspend trading in the event of rapid declines, claiming that they would prevent such panic sales. The one-day crash of Black Monday, October 19, 1987, however, was even more severe than the crash of 1929, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell a full 22.6%.[14] (The markets quickly recovered, posting the largest one-day increase since 1933 only two days later.)

[edit] Effects and academic debate

Together, the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression "...was the biggest financial crisis of the" 20th century.[25] "The panic of October 1929 has come to serve as a symbol of the economic contraction that gripped the world during the next decade."[24] "The crash of 1929 caused 'fear mixed with a vertiginous disorientation', but 'shock was quickly cauterized with denial, both official and mass-delusional'."[26] "The falls in share prices on October 24 and 29, 1929 ... were practically instantaneous in all financial markets, except Japan."[27] The Wall Street Crash had a major impact on the U.S. and world economy, and it has been the source of intense academic debate—historical, economic and political—from its aftermath until the present day. "Some people believed that abuses by utility holding companies contributed to the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Depression that followed."[1] "Many people blamed the crash on commercial banks that were too eager to put deposits at risk on the stock market. "[28]

The "1929 crash brought the Roaring Twenties shuddering to a halt."[29] As "tentatively expressed" by "economic historian Charles Kindleberger", in 1929 there was no "...lender of last resort effectively present", which, if it had existed and were "properly exercised", would have been "key in shortening the business slowdown[s] that normally follows financial crises."[27] The crash marked the beginning of widespread and long-lasting consequences for the United States. The main question is: Did the "'29 Crash spark The Depression?",[30] or did it merely coincide with the bursting of a credit-inspired economic bubble? The decline in stock prices caused bankruptcies and severe macroeconomic difficulties including business closures, firing of workers and other economic repression measures. The resultant rise of mass unemployment and the depression is seen as a direct result of the crash, though it is by no means the sole event that contributed to the depression; it is usually seen as having the greatest impact on the events that followed. Therefore the Wall Street Crash is widely regarded as signaling the downward economic slide that initiated the Great Depression.

True or not, the consequences were dire for almost everybody. "Most academic experts agree on one aspect of the crash: It wiped out billions of dollars of wealth in one day, and this immediately depressed consumer buying."[30] The failure set off a worldwide run on US gold deposits (i.e., the dollar), and forced the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates into the slump. Some 4,000 lenders were ultimately driven to the wall. Also, the uptick rule,[31] which "...allowed short selling only when the last tick in a stock’s price was positive," "...was implemented after the 1929 market crash to prevent short sellers from driving the price of a stock down in a bear run."[32]

Many academics see the Wall Street Crash of 1929 as part of a historical process that was a part of the new theories of boom and bust. According to economists such as Joseph Schumpeter and Nikolai Kondratieff the crash was merely a historical event in the continuing process known as economic cycles. The impact of the crash was merely to increase the speed at which the cycle proceeded to its next level.

Milton Friedman's A Monetary History of the United States, co-written with Anna Schwartz, makes the argument that what made the "great contraction" so severe was not the downturn in the business cycle, trade protectionism, or the 1929 stock market crash. But instead what plunged the country into a deep depression was the collapse of the banking system during three waves of panics over the 1930-33 period.[33]

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b Pyramid structures brought down by Wall Street Crash The Times

- ^ Role of 'new Tinkerman' tailor-made for Benítez The Times

- ^ "Stock Markets Explained". Times Online. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/money/reader_guides/article3849751.ece. "The most savage bear market of all time was the Hall Street Crash of 1929-1932, in which share prices fell by 89 per cent."

- ^ Economics focus: The Great Depression The Economist

- ^ Reactions of the Wall Street slump The Economist

- ^ America gets depressed by thoughts of 1929 revisited The Sunday Times

- ^ Edward Teach - CFO Magazine (May 1, 2007). "The Bright Side of Bubbles - CFO.com". Cfo.com. http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/9059304/c_9064230. Retrieved on 2008-10-01.

- ^ Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

- ^ Jude Wanniski The Way the World Works ISBN 0895263440, 1978 Gateway Editions

- ^ DJIA 1929 to Present (Yahoo! Finance)

- ^ "U.S. Industrial Stocks Pass 1929 Peak", The Times, 24 November 1954, p. 12.

- ^ a b Salesman, Richard M. "The Cause and Consequences of the Great Depression, Part 1: What Made the Roaring '20s Roar" in The Intellectual Activist, ISSN 0730-2355, June, 2004, p. 16. Emphasis original.

- ^ "Timeline: A selected Wall Street chronology". PBS. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/crash/timeline/timeline2.html. Retrieved on 2008-09-30.

- ^ a b The Panic of 2008? What Do We Name the Crisis? The Wall Street Journal

- ^ "NYSE, New York Stock Exchange > About Us > History > Timeline > Timeline". Nyse.com. http://www.nyse.com/about/history/timeline_trading.html. Retrieved on 2008-10-01.

- ^ a b Linton Weeks. "History's Advice During A Panic? Don't Panic : NPR". Npr.org. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=94721470. Retrieved on 2008-10-01.

- ^ "American Experience | The Crash of 1929 | Timeline | PBS". Pbs.org. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/crash/timeline/timeline2.html. Retrieved on 2008-10-01.

- ^ pbs.org – New York: A Documentary Film

- ^ "Historical Index Data – Market Data Center". Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/2_3047-djia_alltime.html. Retrieved on 2008-10-14.

- ^ Liquid Markets.

- ^ "Crashes, Bangs & Wallops". Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/7173bb6a-552a-11dd-ae9c-000077b07658.html. Retrieved on 2008-09-30. "At the turn of the 20th century stock market speculation was restricted to professionals, but the 1920s saw millions of "ordinary Americans" investing in the New York Stock Exchange. By August 1929, brokers had lent small investors more than two-thirds of the face value of the stocks they were buying on margin - more than $8.5bn was out on loan."

- ^ Shiller, Robert (2005-03-17). "Irrational Exuberance, Second Edition". Princeton University Press. http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/s7922.html. Retrieved on 2007-02-03.

- ^ Scardino, Albert (1987-10-21). "The Market Turmoil: Past lessons, present advice; Did '29 Crash Spark The Depression?". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE4DC1F3BF932A15753C1A961948260. Retrieved on 2008-09-30. "Yet historians and economists still differ over whether the collapse of share prices caused the international catastrophe known as the Great Depression or simply reflected the underlying weakness of the domestic economy."

- ^ a b Scardino, Albert (1987-10-21). "The Market Turmoil: Past lessons, present advice; Did '29 Crash Spark The Depression?". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE4DC1F3BF932A15753C1A961948260.

- ^ Paulson affirms Bush assessment The Washington Times

- ^ Downtown bestiary Times Online

- ^ a b Crashes, Bangs & Wallops Financial Times

- ^ Death of the Brokerage: The Future of Wall Street National Public Radio

- ^ Kaboom!...and bust. The crash of 2008 The Times

- ^ a b The Market Turmoil: Past lessons, present advice; Did '29 Crash Spark The Depression? The New York Times

- ^ Practice has plenty of historical precedents - Financial Times

- ^ Funds want ‘uptick’ rule back Financial Times

- ^ Panic control The Washington Times

[edit] Further reading

- Bierman, Harold. "The 1929 Stock Market Crash". EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. August 11, 2004. URL http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/Bierman.Crash

- Brooks, John. (1969). Once in Golconda: A True Drama of Wall Street 1920-1938. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-393-01375-8.

- Galbraith, John Kenneth. (1954). The Great Crash: 1929. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-85999-9.

- Klein, Maury. (2001). Rainbow's End: The Crash of 1929. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-13516-4.

- Klingaman, William K. (1989). 1929: The Year of the Great Crash. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-060-16081-0.

- Rothbard, Murray N. "America's Great Depression"

- Salsman, Richard M. “The Cause and Consequences of the Great Depression” in The Intellectual Activist, ISSN 0730-2355.

-

- “Part 1: What Made the Roaring ’20s Roar”, June, 2004, pp. 16–24.

- “Part 2: Hoover’s Progressive Assault on Business”, July, 2004, pp. 10–20.

- “Part 3: Roosevelt's Raw Deal”, August, 2004, pp. 9–20.

- “Part 4: Freedom and Prosperity”, January, 2005, pp. 14–23.

- Shachtman, Tom. (1979). The Day America Crashed. New York: G.P. Putnam. ISBN 0-399-11613-3.

- Thomas, Gordon, and Max Morgan-Witts. (1979). The Day the Bubble Burst: A Social History of the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-14370-2.

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||