Power chord

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In music, a power chord ![]() Play (help·info) (also fifth chord) is a note plus the note a fifth above, usually played on electric guitar. Theorists are divided on whether the term chord is appropriate, with some requiring the third of the chord for it to be considered an actual chord. Therefore, some would consider it to be a dyad or simply interval. However this usage is accepted among guitar players. In other words, it's a chord with no 3rd.

Play (help·info) (also fifth chord) is a note plus the note a fifth above, usually played on electric guitar. Theorists are divided on whether the term chord is appropriate, with some requiring the third of the chord for it to be considered an actual chord. Therefore, some would consider it to be a dyad or simply interval. However this usage is accepted among guitar players. In other words, it's a chord with no 3rd.

A power chord is neither major or minor because the intervals between the notes are perfect fifths, and when inverted, perfect fourths. In order for a chord to be considered major or minor the notes in the chord itself must be related by a major or minor interval. However, power chords can 'sound' major or minor to our ears because our brain fills in those missing thirds where it expects them. When the power chord's root is based on a note diatonic in the scale of the song, our ear expects a chord with same root. In addition, such chords are usually played with octave doubling, which makes a different sound than just a 5th.

Power chords are used where a distorted, "overdriven" tone is used, because including the third tends to result in unpleasant harmonics and an indistinct root note when combined with the additional overtones added by an amplifier or distortion pedal. They have the added advantage of being relatively easy to play (see "Fingering" below).

Although the use of the term "power chord" has, to some extent, spilled over into the vocabulary of other instrumentalists, namely keyboard and synthesizer players, it remains essentially a part of rock guitar culture and is most strongly associated with the overdriven electric guitar styles of hard rock, heavy metal, punk rock, and similar genres. When the same interval is found in traditional and classical music, the harmonic interpretation will be much more varied, not necessarily implying a triad with the third degree omitted.

Power chords are sometimes notated 5, as in C5 (C power chord), in which case it specifically refers to playing the root and fifth of the chord, in this case C and G, possibly inverted, and possibly with octave doublings. It can also sound different if you keep adding octaves of the fifth and octaves of the bass note, as it will sound higher pitched with less power, but still a power chord. This an example of multiple octave doublings.

Contents |

[edit] History

There is disagreement over which was the first record to feature power chords. Link Wray is commonly cited as having introduced power chords with his hit 1958 instrumental "Rumble". Wray used a pencil to punch holes into the loudspeaker of his amplifier in order to replicate a distortion effect first improvised at a show in Fredericksburg, Virginia. [1]. Wray pioneered electric guitar distortions, like overdrive and fuzz, and was the first guitarist to use power chords to play a song's melody[citation needed].

However, power chords can also be found in earlier, less commercially successful recordings. Robert Palmer has argued that blues guitarists Willie Johnson and Pat Hare, both of whom played for Sun Records in the early 1950s, were the true originators of the power chord, citing as evidence Johnson's playing on Howlin' Wolf's "How Many More Years" (recorded 1951) and Hare's playing on James Cotton's "Cotton Crop Blues" (recorded 1954).[2]

Another early hit song built around power chords was "You Really Got Me" by the Kinks, released in 1964 (Walser 1993, p.9):

Early heavy metal bands such as Black Sabbath and Deep Purple also helped to popularize power chords.

Pete Townshend, having been influenced by Link Wray, is often credited for introducing the term and the power chord in general and is an avid user of them.[citation needed]

[edit] Performance techniques

Power chords are often performed within a single octave, as this results in the closest matching of overtones. Octave doubling is sometimes done in power chords. Power chords are often pitched in a middle register. If they are too low, they tend to sound unclear and boomy. When played too high they lack depth and power.

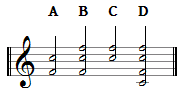

Shown are four examples of an F5 chord. A common voicing is the 1-5 perfect fifth (A), to which the octave can be added, 1-5-1 (B). A perfect fourth 5-1 (C) is also a power chord, as it implies the "missing" lower 1 pitch. Either or both of the pitches may be doubled an octave above or below (D is 5-1-5-1, commonly used by indie rock guitarist Matthew Mollison), which leads to another common variation, 5-1-5.

Pete Townshend of The Who is famous for his use of power chords. "Won't Get Fooled Again" and "Baba O'Riley" are both good examples of the sound produced.

[edit] Fingering

Perhaps the most common implementation is I-V-I', that is, the root note, a note a fifth above the root, and a note an octave above the root. When the strings are a fourth apart, especially the lower four strings in standard tuning, the lowest note is played with some fret on some string and the higher two notes are two frets higher on the next two strings. Using standard tuning, notes on the first or second string need to be played one fret higher than this. (A bare fifth without octave doubling is the same, except that the highest of the three strings, in parentheses below, is not played. A bare fifth with the bass note on the second string has the same fingering as one on the fifth or sixth string.)

G5 A5 D5 E5 G5 A5 D5 A5

E||----------------------------------------------(10)---(5)----|

B||--------------------------------(8)----(10)----10-----5-----|

G||------------------(7)----(9)-----7------9------7------2-----|

D||----(5)----(7)-----7------9------5------7-------------------|

A||-----5------7------5------7---------------------------------|

E||-----3------5-----------------------------------------------|

An inverted bare fifth, i.e. a bare fourth, can be played with one finger, as in the example below, from the riff in Smoke on the Water by Deep Purple:

G5/D Bb5/F C5/G G5/D Bb5/F Db5/Ab C5/G

E||------------------------|----------------------|

B||------------------------|----------------------|

G||*--0---3---5------------|---0---3---6---5------|

D||*--0---3---5------------|---0---3---6---5------|

A||------------------------|----------------------|

E||------------------------|----------------------|

|-----------------------|---------------------||

|-----------------------|---------------------||

|--0---3---5---3---0----|--------------------*||

|--0---3---5---3---0----|--------------------*||

|-----------------------|---------------------||

|-----------------------|---------------------||

An also used implementation is V-I'-V', that is, a note a fourth below the root, the root note, and a note a fifth above the root. (This is sometimes called a "fourth chord", but usually the second note is taken as the root, although it's not the lowest one.) When the strings are a fourth apart, the lower two notes are played with some fret on some two strings and the highest note is two frets higher on the next string. Of course, using standard tuning, notes on the first or second string need to be played one fret higher.

D5 E5 G5 A5 D5 A5 D5 G5

E||-----------------------------------------------5------10----|

B||---------------------------------10-----5------3------8-----|

G||-------------------7------9------7------2-----(2)----(7)----|

D||-----7------9------5------7-----(7)----(2)------------------|

A||-----5------7-----(5)----(7)--------------------------------|

E||----(5)----(7)----------------------------------------------|

With the drop D tuning, power chords with the base on the sixth string can be played with one finger, and D power chords can be played on three open strings.

As can be seen, they almost never comprise of more than 3 strings in order to maintain the alternating dominant and recessive notes.

D5 E5

E||----------------

B||----------------

G||----------------

D||--0-------2-----

A||--0-------2-----

D||--0-------2-----

Occasionally, open, "stacked" power chords with more than three notes are used in drop D.

E||--7-------1-----------------------6-------5--- B||--7-------3-------3-------5-------6-------5--- G||--7-------3-------2-------4-------6-------2--- D||--9-------1-------0-------2-------4-------2--- A||--9-------1-------0-------2-------4-------0--- D||--9-------1-------0-------2-------4-------0---

[edit] References

- ^ Zitz, Michael. Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, VA. "Fredericksburg Offered up Fertile Spot for Rock's Roots" December 20, 2005.

- ^ Robert Palmer, "Church of the Sonic Guitar", pp. 13-38 in Anthony DeCurtis, Present Tense, Duke University Press, 1992, pp. 24-27.

| This article includes a list of references or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (February 2008) |

- Crawshaw, Edith A. H. (1939). "What's Wrong with Consecutive Fifths?". The Musical Times, Vol. 80, No. 1154. (Apr., 1939), pp. 256-257.

- Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, VA "Fredericksburg Offered up Fertile Spot for Rock's Roots" December 20, 2005.

- Walser, Robert (1993). Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6260-2.

[edit] See also

[edit] External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||