Aspartame

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Aspartame[1] | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| IUPAC name |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 22839-47-0 |

| SMILES |

|

| ChemSpider ID | |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C14H18N2O5 |

| Molar mass | 294.3 g mol−1 |

| Melting point |

246–247 °C |

| Boiling point |

decomposes |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) Infobox references |

|

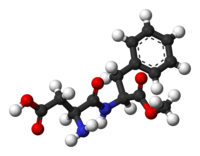

Aspartame (or APM) (pronounced /ˈæspɚteɪm/ or /əˈspɑrteɪm/) is the name for an artificial, non-saccharide sweetener, aspartyl-phenylalanine-1-methyl ester; that is, a methyl ester of the dipeptide of the amino acids aspartic acid and phenylalanine. It has been the subject of controversy since its initial approval in 1974.

Contents |

Marketing

This sweetener is marketed under a number of trademark names, including Equal, NutraSweet, and Canderel, and is an ingredient of approximately 6,000 consumer foods and beverages sold worldwide. It is commonly used in diet soft drinks, and is provided as a table condiment in some countries. It is also used in some brands of chewable vitamin supplements and common in many sugar-free chewing gums and has now been found in some chewing gums that are not sugar free. However, aspartame is not always suitable for baking because it often breaks down when heated and loses much of its sweetness. In the European Union, it is also known under the E number (additive code) E951. Aspartame is also one of the sugar substitutes used by people with diabetes.

Because sucralose, unlike aspartame, retains its sweetness after being heated, it has become more popular as an ingredient. This, along with differences in marketing and changing consumer preferences, has caused aspartame to lose market share to sucralose.[2][3]

Chemistry

Aspartame is the methyl ester of the dipeptide of the natural amino acids L-aspartic acid and L-phenylalanine. Under strongly acidic or alkaline conditions, aspartame may generate methanol by hydrolysis. Under more severe conditions, the peptide bonds are also hydrolyzed, resulting in the free amino acids.[4]

In certain markets aspartame is manufactured using a genetically modified variation of E. coli.[5][6]

Properties and use

Aspartame is an artificial sweetener. It is 180 times sweeter than sugar in typical concentrations, without the high energy value of sugar. While aspartame, like other peptides, has a caloric value of 4 kilocalories (17 kilojoules) per gram, the quantity of aspartame needed to produce a sweet taste is so small that its caloric contribution is negligible, which makes it a popular sweetener for those trying to avoid calories from sugar. The taste of aspartame is not identical to that of sugar: the sweetness of aspartame has a slower onset and longer duration than that of sugar. Blends of aspartame with acesulfame potassium—usually listed in ingredients as acesulfame K—are alleged to taste more like sugar, and to be sweeter than either substitute used alone.

Like many other peptides, aspartame may hydrolyze (break down) into its constituent amino acids under conditions of elevated temperature or high pH. This makes aspartame undesirable as a baking sweetener, and prone to degradation in products hosting a high-pH, as required for a long shelf life. The stability of aspartame under heating can be improved to some extent by encasing it in fats or in maltodextrin. The stability when dissolved in water depends markedly on pH. At room temperature, it is most stable at pH 4.3, where its half-life is nearly 300 days. At pH 7, however, its half-life is only a few days. Most soft-drinks have a pH between 3 and 5, where aspartame is reasonably stable. In products that may require a longer shelf life, such as syrups for fountain beverages, aspartame is sometimes blended with a more stable sweetener, such as saccharin.[7]

In products such as powdered beverages, the amine in aspartame can undergo a Maillard reaction with the aldehyde groups present in certain aroma compounds. The ensuing loss of both flavor and sweetness can be prevented by protecting the aldehyde as an acetal.

Public opinion is that aspartame creates an odd aftertaste to some people, many describe it as a non-flavor or something such as a watery aftertaste.[who?]

Discovery and approval

Aspartame was discovered in 1965 by James M. Schlatter, a chemist working for G.D. Searle & Company. Schlatter had synthesized aspartame in the course of producing an anti-ulcer drug candidate. He discovered its sweet taste serendipitously when he licked his finger, which had accidentally become contaminated with aspartame.[8]

Following initial safety testing, two activists against food additives asserted these tests had indicated aspartame may cause cancer in rats; as a result, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did not approve its use as a food additive in the United States for many years.[9] In 1980, the FDA convened a Public Board of Inquiry (PBOI) consisting of independent advisors charged with examining the purported relationship between aspartame and brain cancer. The PBOI concluded that aspartame does not cause brain damage, but it recommended against approving aspartame at that time, citing unanswered questions about cancer in laboratory rats. A U.S. FDA task force teams investigated allegations of errors in the pre-approval research conducted by the manufacturer and found only minor discrepancies that did not affect the study outcomes.[10][11] Citing data from a Japanese study that had not been available to the members of the PBOI,[12] and after seeking advice from an expert panel that found fault with statistical analyses underlying the PBOI's hesitation,[13] FDA commissioner Hayes approved aspartame for use in dry goods.[14] In 1983, the FDA further approved aspartame for use in carbonated beverages, and for use in other beverages, baked goods, and confections in 1993. In 1996, the FDA removed all restrictions from aspartame allowing it to be used in all foods.

In 1985, Monsanto bought G.D. Searle—and the aspartame business became a separate Monsanto subsidiary, the NutraSweet Company. On May 25, 2000, Monsanto sold it to J.W. Childs Equity Partners II L.P.[15] The U.S. patent on aspartame expired in 1992. Since then, the company has competed for market share with other manufacturers, including Ajinomoto, Merisant and the Holland Sweetener Company. The latter stopped making the chemical in late 2006 because "global aspartame markets are facing structural oversupply, which has caused worldwide strong price erosion over the last five years", making the business "persistently unprofitable".[16]

Several European Union countries approved aspartame in the 1980s, with EU-wide approval in 1994. The European Commission Scientific Committee on Food reviewed subsequent safety studies and reaffirmed the approval in 2002. The European Food Safety Authority reported in 2006 that the previously established Adequate Daily Intake was appropriate, after reviewing yet another set of studies.[17]

Metabolism

Upon ingestion, aspartame breaks down into natural residual components, including aspartic acid, phenylalanine, methanol, and further breakdown products including formaldehyde,[18] formic acid, and a diketopiperazine.

High levels of the naturally-occurring essential amino acid phenylalanine are a health hazard to those born with phenylketonuria (PKU), a rare inherited disease that prevents phenylalanine from being properly metabolized. Since individuals with PKU must consider aspartame as an additional source of phenylalanine, foods containing aspartame sold in the United States must state "Phenylketonurics: Contains Phenylalanine" on their product labels.

In the UK, foods that contain aspartame must list the chemical among the product's ingredients and carry the warning "Contains a source of phenylalanine" – this is usually at the foot of the list of ingredients. Manufacturers should print '"with sweetener(s)" on the label close to the main product name' on foods that contain "sweeteners such as aspartame" or "with sugar and sweetener(s)" on "foods that contain both sugar and sweetener". "This labelling is a legal requirement", says the country's Food Standards Agency.[19]

Health concerns

Aspartame has been the subject of controversy regarding its safety since its initial approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1974.[20][21] Some scientific studies, combined with allegations of conflicts of interest in the sweetener's FDA approval process, have been the focus of vocal activism, conspiracy theories and hoaxes regarding postulated risks of aspartame.[22][23]

A 2007 safety evaluation found that the weight of existing scientific evidence indicates that aspartame is safe at current levels of consumption as a non-nutritive sweetener.[24] The sources and claims of many alleged aspartame dangers and conspiracies have been the subject of critical examination. In 1987, the U.S. Government Accountability Office concluded that the food additive approval process had been followed for aspartame.[20][25] Based on government research reviews and recommendations from advisory bodies such as the European Commission’s Scientific Committee on Food and the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives, aspartame has been found to be safe for human consumption by more than ninety countries worldwide.[26][27] In 1999, FDA scientists described the safety of aspartame as "clear cut" and stated that the product is "one of the most thoroughly tested and studied food additives the agency has ever approved."[28]

References

- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 861.

- ^ John Schmeltzer (2004-12-02). "Equal fights to get even as Splenda looks sweet"] (subscription required). Chicago Tribune. http://www.chicagotribune.com/business/chi-0412020391dec02,1,2234783.story?coll=chi-business-hed. Retrieved on 2007-07-04.

- ^ Carney, By Beth (2005-01-19). "It's Not All Sweetness for Splenda". BusinessWeek: Daily Briefing. http://www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/jan2005/nf20050119_5391_db014.htm. Retrieved on 2008-09-05.

- ^ David J. Ager, David P. Pantaleone, Scott A. Henderson, Alan R. Katritzky, Indra Prakash, D. Eric Walters (1998). "Commercial, Synthetic Nonnutritive Sweeteners". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 37 (13-24): 1802–1817. doi:.

- ^ The Independent, Sunday, 20 June 1999

- ^ Method for production of L-phenylalanine by recombinant E. coli ATCC 67460

- ^ "Fountain Beverages in the US" (PDF). The Coca-Cola Company. May 2007. http://www.thecoca-colacompany.com/mail/goodanswer/us_fountain_beverages.pdf.

- ^ How Products Are Made: Aspartame

- ^ Andrew Cockburn, Rumsfeld: His Rise, Fall, and Catastrophic Legacy, Simon and Schuster 2007, pp. 63-64

- ^ "U.S. GAO - HRD-87-46 Food and Drug Administration: Food Additive Approval Process Followed for Aspartame, June 18, 1987". 94-96. http://www.gao.gov/docdblite/info.php?rptno=HRD-87-46. Retrieved on 2008-09-05.

- ^ Testimony of Dr. Adrian Gross, Former FDA Investigator to the U.S. Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, November 3, 1987. Hearing title: "NutraSweet Health and Safety Concerns." Document # Y 4.L 11/4:S.HR6.100, page 430-439.

- ^ FDA Statement on Aspartame, November 18, 1996

- ^ "U.S. GAO - HRD-87-46 Food and Drug Administration: Food Additive Approval Process Followed for Aspartame, June 18, 1987". 53. http://www.gao.gov/docdblite/info.php?rptno=HRD-87-46. Retrieved on 2008-09-05.

- ^ Food Additive Approval Process Followed for Aspartame, Food and Drug Administration, June 1987

- ^ J.W. Childs Equity Partners II, L.P, Food & Drink Weekly, June 5, 2000

- ^ html b1?release id=115447

- ^ EFSA ::. Opinion of the Scientific Panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food (AFC) related to a new long-term carcinogenicity study on aspartame

- ^ C. Trocho, R. Pardo, I. Rafecas, J. Virgili, X. Remesar, J. A. Fernandez-Lopez and M. Alemany (1998). "Formaldehyde derived from dietary aspartame binds to tissue components in vivo". Life Sciences 63 (5): 337–349. doi:.

- ^ Aspartame - Labelling, UK Food Standards Agency, 18 July 2006. Retrieved on 2007-07-22.

- ^ a b GAO 1987. "Food Additive Approval Process Followed for Aspartame" United States General Accounting Office, GAO/HRD-87-46, June 18, 1987

- ^ Sugarman, Carole (1983-07-03). "Controversy Surrounds Sweetener". Washington Post. pp. D1-2. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/washingtonpost_historical/access/125899752.html?dids=125899752:125899752&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

- ^ Falsifications and Facts about Aspartame - An analysis of the origins of aspartame disinformation, by the University of Hawaii

- ^ Aspartame Warning About.com - the Nancy Markle chain email.

- ^ Magnuson BA, Burdock GA, Doull J, et al (2007). "Aspartame: a safety evaluation based on current use levels, regulations, and toxicological and epidemiological studies". Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 37 (8): 629–727. doi:. PMID 17828671.

- ^ GAO 1986. "Six Former HHS Employees' Involvement in Aspartame's Approval." United States General Accounting Office, GAO/HRD-86-109BR, July 1986.

- ^ Health Canada: "Aspartame - Artificial Sweeteners". http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/securit/addit/sweeten-edulcor/aspartame-eng.php. Retrieved on 2008-11-08.

- ^ Food Standards Australia New Zealand: "Food Standards Australia New Zealand: Aspartame (September 2007)". http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/newsroom/factsheets/factsheets2007/aspartameseptember203703.cfm. Retrieved on 2008-11-08.

- ^ Henkel, John (November–December 1999). "Sugar Substitutes: Americans Opt for Sweetness and Lite". FDA Consumer. http://www.fda.gov/fdac/features/1999/699_sugar.html. Retrieved on January 29, 2009.

|

|||||