Akira Kurosawa

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2008) |

- In this Japanese name, the family name is Kurosawa.

| Akira Kurosawa | |

|---|---|

Akira Kurosawa on set |

|

| Born | 23 March 1910 Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan |

| Died | 6 September 1998 (aged 88) Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation | director, producer & screenwriter |

| Spouse(s) | Yôko Yaguchi (1921-1985) |

Akira Kurosawa (Kyūjitai: 黒澤 明, Shinjitai: 黒沢 明 Kurosawa Akira, 23 March 1910 – 6 September 1998) was a legendary Japanese filmmaker, producer, screenwriter and editor. His first credited film as director, (Sanshiro Sugata), was released in 1943, his last as director, (Madadayo), in 1993. His many awards include the Légion d'honneur and an Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Contents |

[edit] Life

Akira Kurosawa was born to Isamu and Shima Kurosawa on 23 March 1910. He was the youngest of eight children born to the Kurosawas in a suburb of Tokyo. Shima Kurosawa was forty years old at the time of Akira's birth and his father Isamu was forty-five. Akira Kurosawa grew up in a household with three older brothers and four older sisters. Of his three older brothers, one died before Akira was born and one was already grown and out of the household. One of his four older sisters had also left the home to begin her own family before Kurosawa was born. Kurosawa's next-oldest sibling, a sister he called "Little Big Sister," also died suddenly after a short illness when he was ten years old.

Kurosawa's father worked as the director of a junior high school operated by the Japanese military and the Kurosawas descended from a line of former samurai. Financially, the family was above average. Isamu Kurosawa embraced western culture both in the athletic programs that he directed and by taking the family to see films, which were then just beginning to appear in Japanese theaters. Later, when Japanese culture turned away from western films, Isamu Kurosawa continued to believe that films were a positive educational experience.

In primary school, Akira Kurosawa was encouraged to draw by a teacher who took an interest in mentoring his talents. His older brother, Heigo, had a profound impact on him. Heigo was very intelligent and won several academic competitions, but also had what was later called a cynical or dark side. In 1923, the Great Kantō earthquake destroyed Tokyo and left 100,000 people dead. In the wake of this event, Heigo, 17, and Akira, 13, made a walking tour of the devastation. Corpses of humans and animals were piled everywhere. When Akira would attempt to turn his head away, Heigo urged him not to. According to Akira, this experience would later instruct him that to look at a frightening thing head-on is to defeat its ability to cause fear.

Heigo eventually began a career as a benshi in Tokyo film theaters. Benshi narrated silent films for the audience and were a uniquely Japanese addition to the theater experience. However, with the impact of talking pictures on the rise, benshi were losing work all over Japan. Heigo organized a benshi strike that failed. Akira was likewise involved in labor-management struggles, writing several articles for a radical newspaper while improving and expanding his skills as a painter and reading literature.

When Akira Kurosawa was in his early 20s, his older brother Heigo committed suicide. Four months later, the oldest of Kurosawa's brothers also died, leaving Akira as the only surviving son of an original four at age 23.

Kurosawa's wife was actress Yoko Yaguchi. He had two children with her: a son named Hisao and a daughter named Kazuko.

Kurosawa was a notoriously lavish gourmet, and spent huge quantities of money on film sets providing an incredibly large quantity of fine delicacies, especially meat, for the cast and crew, although the meat was sometimes left over from recording sound effects of the sound of blades cutting flesh in the many swordfight scenes.[1]

Kurosawa was a close friend of director Ishiro Honda, who directed the original Godzilla.

[edit] Early career

In 1936, Kurosawa learned of an apprenticeship program for directors through a major film studio, PCL (which later became Toho). He was hired and worked as an assistant director to Kajiro Yamamoto. After his directorial debut with Sanshiro Sugata, his next few films were made under the watchful eye of the wartime Japanese government and sometimes contained nationalistic themes. For instance, The Most Beautiful is a propaganda film about Japanese women working in a military optics factory. Judo Saga 2 portrays Japanese judo as superior to western (American) boxing.

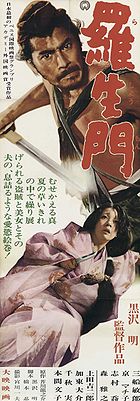

His first post-war film No Regrets for Our Youth, by contrast, is critical of the old Japanese regime and is about the wife of a left-wing dissident who is arrested for his political leanings. Kurosawa made several more films dealing with contemporary Japan, most notably Drunken Angel and Stray Dog. However, it was his period film Rashomon that made him internationally famous and won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

[edit] Directorial approach

Kurosawa had a distinctive cinematic technique, which he had developed by the 1950s, and which gave his films a unique look. He liked using telephoto lenses for the way they flattened the frame and also because he believed that placing cameras farther away from his actors produced better performances. He also liked using multiple cameras, which allowed him to shoot an action scene from different angles. Another Kurosawa trademark was the use of weather elements to heighten mood: for example the heavy rain in the opening scene of Rashomon, and the final battle in Seven Samurai, the intense heat in Stray Dog, the cold wind in Yojimbo, the snow in Ikiru, and the fog in Throne of Blood. Kurosawa also liked using frame wipes, sometimes cleverly hidden by motion within the frame, as a transition device.

He was known as "Tenno", literally "Emperor", for his dictatorial directing style. He was a perfectionist who spent enormous amounts of time and effort to achieve the desired visual effects. In Rashomon, he dyed the rain water black with calligraphy ink in order to achieve the effect of heavy rain, and ended up using up the entire local water supply of the location area in creating the rainstorm. In the final scene of Throne of Blood, in which Mifune is shot by arrows, Kurosawa used real arrows shot by expert archers from a short range, landing within centimetres of Mifune's body. In Ran, an entire castle set was constructed on the slopes of Mt. Fuji only to be burned to the ground in a climactic scene.

Other stories include demanding a stream be made to run in the opposite direction in order to get a better visual effect, and having the roof of a house removed, later to be replaced, because he felt the roof's presence to be unattractive in a short sequence filmed from a train.

His perfectionism also showed in his approach to costumes: he felt that giving an actor a brand new costume made the character look less than authentic. To resolve this, he often gave his cast their costumes weeks before shooting was to begin and required them to wear them on a daily basis and "bond with them." In some cases, such as with Seven Samurai, where most of the cast portrayed poor farmers, the actors were told to make sure the costumes were worn down and tattered by the time shooting started.

Kurosawa did not believe that "finished" music went well with film. When choosing a musical piece to accompany his scenes, he usually had it stripped down to one element (e.g., trumpets only). Only towards the end of his films are more finished pieces heard.

[edit] Influences

A notable feature of Kurosawa's films is the breadth of his artistic influences. Some of his plots are based on William Shakespeare's works: Ran is loosely based on King Lear, Throne of Blood is based on Macbeth, while The Bad Sleep Well parallels Hamlet, but is not affirmed to be based on it. Kurosawa also directed film adaptations of Russian literary works, including The Idiot by Dostoevsky and The Lower Depths, a play by Maxim Gorky. Ikiru was inspired by Leo Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Dersu Uzala was based on the 1923 memoir of the same title by Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev. Story lines in Red Beard can be found in The Insulted and Humiliated by Dostoevsky.

High and Low was based on King's Ransom by American crime writer Ed McBain, Yojimbo may have been based on Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest and also borrows from American Westerns, and Stray Dog was inspired by the detective novels of Georges Simenon. When Kurosawa got to meet John Ford, an American film director commonly said to be the most influential to Kurosawa, Ford simply said, "You really like rain." Kurosawa responded, "You've really been paying attention to my films."[2]

Despite criticism by some Japanese critics that Kurosawa was "too Western", he was deeply influenced by Japanese culture as well, including the Kabuki and Noh theaters and the Jidaigeki (period drama) genre of Japanese cinema.

[edit] Influence

Seven Samurai was remade as The Magnificent Seven.

Rashomon was remade by Martin Ritt in 1964's The Outrage.

Yojimbo was the basis for the Sergio Leone western A Fistful of Dollars and two Bruce Willis films, prohibition-era Last Man Standing.

The Hidden Fortress is an acknowledged influence on George Lucas's Star Wars films, in particular Episodes IV and VI and most notably in the characters of R2-D2 and C-3PO. Lucas also used a modified version of Kurosawa's wipe transition effect throughout the Star Wars saga.

Remakes for Ikiru and High and Low are in progress.

[edit] Collaboration

During his most productive period, from the late 40s to the mid-60s, Kurosawa often worked with the same group of collaborators. Fumio Hayasaka composed music for seven of his films — notably Rashomon, Ikiru and Seven Samurai. Many of Kurosawa's scripts, including Throne of Blood, Seven Samurai and Ran were co-written with Hideo Oguni. Yoshiro Muraki was Kurosawa's production designer or art director for most of his films after Stray Dog in 1949, and Asakazu Nakai was his cinematographer on 11 films including Ikiru, Seven Samurai and Ran. Kurosawa also liked working with the same group of actors, especially Takashi Shimura, Tatsuya Nakadai, and Toshirō Mifune. His collaboration with the latter, which began with 1948's Drunken Angel and ended with 1965's Red Beard, is one of the most famous director-actor combinations in cinema history.

[edit] Later films

The film Red Beard marked a turning point in Kurosawa's career in more ways than one. In addition to being his last film with Mifune, it was his last in black-and-white. It was also his last as a major director within the Japanese studio system making roughly a film a year. Kurosawa was signed to direct a Hollywood project, Tora! Tora! Tora!; but 20th Century Fox replaced him with Toshio Masuda and Kinji Fukasaku before it was completed. His next few films were a lot harder to finance and were made at intervals of five years. The first, Dodesukaden, about a group of poor people living around a rubbish dump, was not a success.

After an attempted suicide, Kurosawa went on to make several more films, although he had great difficulty in obtaining domestic financing despite his international reputation. Dersu Uzala, made in the Soviet Union and set in Siberia in the early 20th century, was the only Kurosawa film made outside of Japan and not in the Japanese language. It is about the friendship of a Russian explorer and a nomadic hunter, and won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. Kagemusha, financed with the help of the director's most famous admirers, George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, is the story of a man who is the body double of a medieval Japanese lord and takes over his identity after the lord's death. The film was awarded the Palme d'Or (Golden Palm) at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival (shared with Bob Fosse's All That Jazz). Ran was the director's version of Shakespeare's King Lear, set in medieval Japan (and the only film of Kurosawa's career that he received a "Best Director" Academy Award nomination for). It was by far the largest project of Kurosawa's late career, and he spent a decade planning it and trying to obtain funding, which he was finally able to do with the help of the French producer Serge Silberman. The film was an international success and is generally considered Kurosawa's last masterpiece. In an interview, Kurosawa said that he considered it to be the best film he ever made.

Kurosawa made three more films during the 1990s which were more personal than his earlier works. Dreams is a series of vignettes based on his own dreams. Rhapsody in August is about memories of the Nagasaki atomic bomb and his final film, Madadayo, is about a retired teacher and his former students. Kurosawa died of a stroke in Setagaya, Tokyo, at age 88.

After the Rain (雨あがる Ame Agaru) is a 1998 posthumous film directed by Kurosawa's closest collaborator, Takashi Koizumi, co-produced by Kurosawa Production (Hisao Kurosawa) and starring Tatsuya Nakadai and Shiro Mifune, son of Toshirō Mifune. Screenplay, script and dialogues were both written by Kurosawa himself. The story is based on a short novel by Shugoro Yamamoto, Ame Agaru.

To mark the 99th anniversary of the birth of Akira Kurosawa, Anaheim University launched the Anaheim University Akira Kurosawa School of Film at the Beverly Hills Hotel on March 23rd, 2009, which would have been Kurosawa's 99th birthday. The son of Akira, Hisao Kurosawa attended as Guest of Honor and a special memorial tribute video was played at the event featuring video presentations from Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, Kurosawa's Assistant Director Teruo Nogami and "Dreams" Producer/Nephew of Akira Kurosawa, Mike Inoue. Anaheim University Akira Kurosawa Memorial Tribute

To coincide with the 100th anniversary of Kurosawa's birth, his unfinished documentary Gendai no Noh will be completed and released in 2010. While filming his masterpiece Ran in 1983, Kurosawa experienced a number of problems during production, including financial troubles, and temporarily postponed filming to work on a non-fiction project. The documentary was to be about classic Japanese Noh theater, whose style had a substantial influence on Ran, as well as Throne of Blood and Kagemusha. Only about 50 minutes of footage exist, but to finish the film, an additional hour will be shot using Kurosawa's original screenplay.[3]

[edit] Awards

- 1951 – Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for Rashomon

- 1951 – Academy Award: Best Foreign Language Film for Rashomon

- 1954 – Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival for Seven Samurai

- 1959 – Silver Bear for Best Director at the Berlin Film Festival for The Hidden Fortress

- 1975 – Academy Award: Best Foreign Language Film for Dersu Uzala

- 1980 – Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival for Kagemusha

- 1982 – Japan Foundation: Japan Foundation Award.[4]

- 1982 – Career Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival

- 1984 – Légion d'honneur

- 1985 – Order of Culture

- 1989 – Honorary Academy Award

- 1992 – Praemium Imperiale

- 1999 – Lifetime Achievement Award at the Japanese Academy Awards

- 1990 – Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize

[edit] Filmography

| Year | Title | Japanese | Romanization |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1943 | Sanshiro Sugata aka Judo Saga |

姿三四郎 | Sugata Sanshirō |

| 1944 | The Most Beautiful | 一番美しく | Ichiban utsukushiku |

| 1945 | Sanshiro Sugata Part II aka Judo Saga 2 |

續姿三四郎 | Zoku Sugata Sanshirô |

| The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail | 虎の尾を踏む男達 | Tora no o wo fumu otokotachi | |

| 1946 | No Regrets for Our Youth | わが青春に悔なし | Waga seishun ni kuinashi |

| 1947 | One Wonderful Sunday | 素晴らしき日曜日 | Subarashiki nichiyōbi |

| 1948 | Drunken Angel | 酔いどれ天使 | Yoidore tenshi |

| 1949 | The Quiet Duel | 静かなる決闘 | Shizukanaru ketto |

| Stray Dog | 野良犬 | Nora inu | |

| 1950 | Scandal | 醜聞 | Sukyandaru aka Shūbun |

| Rashomon | 羅生門 | Rashōmon | |

| 1951 | The Idiot | 白痴 | Hakuchi |

| 1952 | Ikiru aka To Live |

生きる | Ikiru |

| 1954 | Seven Samurai | 七人の侍 | Shichinin no samurai |

| 1955 | I Live in Fear aka Record of a Living Being |

生きものの記録 | Ikimono no kiroku |

| 1957 | Throne of Blood aka Spider Web Castle |

蜘蛛巣城 | Kumonosu-jō |

| The Lower Depths | どん底 | Donzoko | |

| 1958 | The Hidden Fortress | 隠し砦の三悪人 | Kakushi toride no san akunin |

| 1960 | The Bad Sleep Well | 悪い奴ほどよく眠る | Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru |

| 1961 | Yojimbo aka The Bodyguard |

用心棒 | Yōjinbō |

| 1962 | Sanjuro | 椿三十郎 | Tsubaki Sanjūrō |

| 1963 | High and Low aka Heaven and Hell |

天国と地獄 | Tengoku to jigoku |

| 1965 | Red Beard | 赤ひげ | Akahige |

| 1970 | Dodesukaden | どですかでん | Dodesukaden |

| 1975 | Dersu Uzala | デルス・ウザーラ | Derusu Uzāra |

| 1980 | Kagemusha | 影武者 | Kagemusha |

| 1985 | Ran | 乱 | Ran |

| 1990 | Dreams aka Akira Kurosawa's Dreams |

夢 | Yume |

| 1991 | Rhapsody in August | 八月の狂詩曲 | Hachigatsu no rapusodī aka Hachigatsu no kyōshikyoku |

| 1993 | Madadayo aka Not Yet |

まあだだよ | Mādadayo |

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Yojimbo.

- ^ A.K., Chris Marker, 1985

- ^ Unfinished footage by Kurosawa to be released

- ^ Japan Foundation Award, 1982.

[edit] Further reading

- Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema ISBN 0-8223-2519-5

- Akira Kurosawa. Something Like An Autobiography. Vintage Books USA, 1983. ISBN 0-394-71439-3

- Stephen Prince. The Warrior's Camera. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-691-01046-3

- Donald Richie, Joan Mellen. The Films of Akira Kurosawa. University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0-520-22037-4

- Stuart Galbraith IV. The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber & Faber, 2002. ISBN 0-571-19982-8

- Toshimitsu Shima. Kurosawa Akira no iru fukei. Shinchosha, 1991. ISBN 4-103-83501-X

- Bert Cardullo. Akira Kurosawa: Interviews (Conversations with Filmmakers). University Press of Mississippi, 2007. ISBN 1-578-06997-1

- James Goodwin. Akira Kurosawa and Intertextual Cinema. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-801-84661-7

- James Goodwin (editor). Perspectives on Akira Kurosawa. G.K. Hall & Co., 1994. ISBN 0-816-11993-7

- Teruyo Nogami. Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies With Akira Kurosawa. Stone Bridge Press, 2006. ISBN 1-933-33009-0

- Manuel Vidal Estevez. Akira Kurosawa. Ediciones Catedra S.A., 2004. ISBN 8-437-61131-8

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Akira Kurosawa |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Akira Kurosawa |

- Akira Kurosawa at the Internet Movie Database

- Anaheim University Akira Kurosawa School of Film Memorial Tribute to Akira Kurosawa

- Senses of Cinema: Great Directors Critical Database

- Great Performances: Kurosawa (PBS)

- Kurosawa project

- Akira Kurosawa News and Information

- 黒澤明 (Akira Kurosawa) (Japanese) at the Japanese Movie Database

- AkiraKurosawa.com

- (Japanese) Akira Kurosawa at Japanese celebrity's grave guide

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Kurosawa, Akira |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 23 March 1910 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ota, Tokyo, Japan |

| DATE OF DEATH | 6 September 1998 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan |