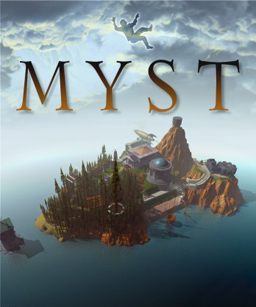

Myst

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

Myst

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Developer(s) | Cyan Worlds |

| Publisher(s) | Brøderbund, Midway Games, Mean Hamster Software, Sunsoft |

| Designer(s) | Robyn and Rand Miller |

| Composer(s) | Robyn Miller |

| Platform(s) | Mac OS, Windows, Saturn, PlayStation, Jaguar CD, AmigaOS, CD-i, 3DO, PlayStation Portable, Nintendo DS, iPhone OS |

| Release date(s) | |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure, puzzle |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

| Rating(s) | ESRB: E PEGI: 3+ RSAC: ALL USK: Alle |

| Media | CD-ROM |

| Input methods | Keyboard, mouse |

Myst is a graphic adventure video game designed and directed by the brothers Robyn and Rand Miller. It was developed by Cyan Worlds, a Spokane, Washington-based studio, and published and distributed by Brøderbund. The Millers began working on Myst in 1991 and released it for the Macintosh computer on September 24, 1993; it was developer Cyan's largest project to date. Remakes and ports of the game have been released for Microsoft Windows, Sega Saturn, PlayStation, Jaguar CD, AmigaOS, CD-i, 3DO, PlayStation Portable, and Nintendo DS by publishers Midway Games, Sunsoft, and Mean Hamster Software.

Myst puts the player in the role of the Stranger, who uses a special book to travel to the island of Myst. There, the player uses other special books written by an artisan and explorer named Atrus to travel to several worlds known as "Ages". Clues found in each of these Ages help reveal the back-story of the game's characters. The game has several endings, depending on the course of action the player takes.

Upon release, Myst was a surprise hit, with critics lauding the ability of the game to immerse players in the fictional world. The game was the best-selling PC game of all time, until The Sims exceeded its sales in 2002.[5] Myst helped drive adoption of the then-nascent CD-ROM format. Myst's success spawned four direct video game sequels as well as several spin-off games and novels.

Contents |

[edit] Gameplay

The gameplay of Myst consists of a first-person journey through an interactive world. The player moves the character by clicking on locations shown in the main display; the scene then crossfades into another frame, and the player can continue to explore. Players can interact with specific objects on some screens by clicking or dragging them.[6] To assist in rapidly crossing areas already explored, Myst has an optional "Zip" feature. When a lightning bolt cursor appears, players can click and skip several frames to another location. While this provides a rapid method of travel, it can also cause players to miss important items and clues.[7] Some items can be carried by the player and read, including journal pages which provide backstory. Players can only carry a single page at a time, and pages return to their original locations when dropped.[8]

To complete the game, the player must explore the seemingly deserted island of Myst.[9] There the player discovers and follows clues to be transported via "linking books" to several "Ages", each of which is a self-contained mini-world. Each Age—named Selenitic, Stoneship, Mechanical, and Channelwood—requires the user to solve a series of logical, interrelated puzzles to complete its exploration. Objects and information discovered in one Age may be required to solve puzzles in another Age, or to complete the game's primary puzzle on Myst. For example, in order to activate a switch, players must first open a safe and use the matches found within to start a boiler.[10]

Apart from its predominantly nonverbal storytelling,[10] Myst's gameplay is unusual among adventuring computer games in several ways. The player is provided with very little backstory at the beginning of the game, and no obvious goals or objectives are laid out. This means that players must simply begin to explore. There are no obvious enemies, no physical violence, and no threat of "dying" at any point,[9] although it is possible to reach a few "losing" endings. There is no time limit to complete the game.[9] The game unfolds at its own pace and is solved through a combination of patience, observation, and logical thinking.[10]

[edit] Plot

The game's instruction manual explains that an unnamed person known as the Stranger stumbles across an unusual book titled "Myst". The Stranger reads the book and discovers a detailed description of an island world. Placing his hand on the last page, the Stranger is whisked away to the world described, and is left with no choice but to explore;[11] the player then gains control and is allowed to wander the new surroundings.

Myst, the island world described in the book, contains a library where two additional books can be found, colored red and blue. These books are traps which hold Sirrus and Achenar, the sons of Atrus, who lives on Myst island with his wife Catherine. Atrus uses an ancient practice to write special "linking books", which transport people to the worlds, or "Ages", that the books describe. From the panels of their books, Sirrus and Achenar tell the Stranger that Atrus is dead, each claiming that the other brother murdered him, and plead for the Stranger to help them escape. However, the books are missing several pages, so the sons' messages are at first riddled with static and unclear.

As the Stranger continues to explore the island, more books are discovered hidden behind complex mechanisms and puzzles. There are four books in total, each linking to a different Age. The Stranger must visit each Age, find the red and blue pages hidden there, and then return to Myst Island. These pages can then be placed in the corresponding books. As the Stranger adds more pages to these books, the brothers can speak more and more clearly. Throughout this process, each brother maintains that the other brother cannot be trusted. After collecting four pages, the brothers can talk clearly enough to tell the Stranger where the fifth page is hidden. If the Stranger gives either brother their fifth page, they will be free. The Stranger is left with a choice to help Sirrus, Achenar, or neither.[12]

Both brothers beg the Stranger not to touch the green book that is stored in the same location as their last pages. They claim that it is a book like their own that will trap the Stranger. In truth, it leads to D'ni, where Atrus is imprisoned. Upon opening the book, Atrus asks the Stranger to bring him a final page that is hidden on Myst Island; without it, he cannot bring his sons to justice.

The game has several endings, depending on the player's actions. Giving either Sirrus or Achenar the final page of their book causes the Stranger to switch places with the son, leaving the player trapped inside the Prison book. Linking to D'ni without the page Atrus asks for leaves both the Stranger and Atrus trapped on D'ni. Linking to D'ni with the page allows Atrus to complete his Myst book and return to the island.[12] Upon returning to the library, the red and blue books are gone, and there are burn marks on the shelves where they used to be.

[edit] Development

|

"We started our design work and realized that we would need to have even more story and history than would be revealed in the game itself. It seemed having that depth was just as important as what the explorer would actually see."

——Rand Miller on developing Myst's fictional history[13]

|

The Myst creative team consisted of the brothers Rand and Robyn Miller, with help from sound designer Chris Brandkamp, graphical artist Chuck Carter, Richard Watson, Bonnie McDowall, and Ryan Miller, who together made up Cyan, Inc. The company had previously only made children's games. Myst was conceived by the brothers as a challenging but aesthetically simple game that would appeal to adults;[9] Myst was not only the largest collaboration Cyan had attempted at the time, but also took the longest to develop.[14] According to Rand Miller, the brothers spent months solely designing the look and puzzles of the Ages,[15] which were influenced by earlier whimsical "worlds" made for children.[13] According to the creators, the game's name, as well as the overall solitary and mysterious atmosphere of the island, was inspired by the book The Mysterious Island by Jules Verne.[9]

At first, the developers had no idea how they would actually create the physical terrain for the Ages.[16] Eventually, they created grayscale heightmaps, extruding them to create changes in elevation. From this basic terrain, textures were painted onto a colormap which was wrapped over the landscapes. Objects such as trees were added to complete the design.[16] Rand noted that attention to detail allowed Myst to deal with the limitations of CD-ROM drives and graphics, stating "A lot can be done with texture…Like finding an interesting texture you can map into the tapestry on the wall, spending a little extra time to actually put the bumps on the tapestry, putting screws in things. These are the things you don't necessarily notice, but if they weren't there, would flag to your subconscious that this is fake."[17]

The game was created on Apple Macintosh computers, principally Macintosh Quadras. The graphics were individual shots of fully rendered rooms. Overall, Myst contains 2,500 frames, one for each possible area the player can explore.[16] Each scene was modeled and rendered in StrataVision 3D, with some additional modeling in Macromedia MacroModel.[16] The images were then edited and enhanced using Photoshop 1.0.[16]

The original Macintosh version of Myst was constructed in Hypercard. Each Age was a unique Hypercard stack. Navigation was handled by the internal button system and HyperTalk scripts, with image and QuickTime movie display passed off to various plugins; essentially, Myst functions as a series of separate multimedia slides linked together by commands.[18] As the main technical constraint that impacted Myst was slow CD-ROM drive read speeds, Cyan had to go to great lengths to make sure all the game elements loaded as quickly as possible.[13] Images were stored as 8-bit PICT resources with custom color palettes and QuickTime still image compression.[16] Animated elements such as movies and object animations were encoded as QuickTime movies with Cinepak compression;[16] in total, there were more than 66 minutes of Quicktime animation.[16] This careful processing made the finished graphics look like truecolor images despite their low bit depth; the stills were reduced in size from 500 KB to around 80 KB.[16]

[edit] Audio

Chris Brandkamp produced most of the ambient and incidental sounds in the game. To make sure the sounds fit, Brandkamp had to wait until the game's visuals were placed in context.[16] Sound effects were drawn from unlikely sources; the noise of a fire in a boiler was created by driving slowly over stones in a driveway, because recording actual fire did not sound like fire burning.[9] The chimes of a large clock tower were simulated using a wrench, then transposed to a lower pitch.[16]

At first, Myst had no music, because the Millers did not want music to interfere with the gameplay.[16] After a few tests, they realized that the background music did not adversely affect the game and, in fact, "seemed to really help the mood of certain places that you were at in the game."[16] Robyn Miller ended up composing 40 minutes of synthesized music that was used in the game and later published as Myst: The Soundtrack.[16] Initially, Cyan released the soundtrack via a mail-order service, but before the release of Myst's sequel, Riven, Virgin Records acquired the rights to releasing the soundtrack,[19] and the CD was rereleased on October 6, 1998.[20]

| Myst: The Soundtrack tracklist | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Title | Length | |||||||

| 1. | "Myst Theme" | 1:30 | |||||||

| 2. | "Treegate" | 1:58 | |||||||

| 3. | "Planetarium" | 1:38 | |||||||

| 4. | "Shipgate" | 1:27 | |||||||

| 5. | "The Tower" | 1:43 | |||||||

| 6. | "The Last Message (Forechamber Theme)" | 2:34 | |||||||

| 7. | "Fortress Ambience Part I" | 0:40 | |||||||

| 8. | "Fortress Ambience Part II" | 0:50 | |||||||

| 9. | "Mechanical Mystgate" | 2:00 | |||||||

| 10. | "Sirrus' Cache" | 1:42 | |||||||

| 11. | "Sirrus' Theme – Mechanical Age" | 1:34 | |||||||

| 12. | "Achenar's Cache" | 1:41 | |||||||

| 13. | "Achenar's Theme – Mechanical Age" | 2:11 | |||||||

| 14. | "Compass Rose" | 1:28 | |||||||

| 15. | "Above Stoneship (Telescope Theme)" | 1:30 | |||||||

| 16. | "Sirrus' Theme – Stoneship Age" | 1:25 | |||||||

| 17. | "Achenar's Theme – Stoneship Age" | 1:40 | |||||||

| 18. | "Selenitic Mystgate" | 1:42 | |||||||

| 19. | "The Temple of Achenar" | 1:35 | |||||||

| 20. | "Sirrus' Theme – Channelwood Age" | 1:32 | |||||||

| 21. | "Achenar's Theme – Channelwood Age" | 2:07 | |||||||

| 22. | "Un-Finale" | 1:57 | |||||||

| 23. | "Finale" | 1:34 | |||||||

| 24. | "Fireplace Theme (bonus track)" | 0:43 | |||||||

| 25. | "Early Selenitic Mystgate (bonus track)" | 1:16 | |||||||

| 26. | "Original Un-Finale (bonus track)" | 1:27 | |||||||

| 41:24 | |||||||||

[edit] Remakes and rereleases

[edit] PC remakes

Myst's success has led to multiple rereleases and remakes. Myst: Masterpiece Edition was an updated version of the original Myst, and was released in May 2000. It featured several improvements over the original game, with the images re-rendered in 24-bit truecolor instead of the original Myst's 8-bit color. The score was re-mastered and sound effects were enhanced, and some cinematics were redone.[21]

realMyst: Interactive 3D Edition was a remake of the Myst computer game released in November 2000 for the PC, and in January 2002 for the Mac. Unlike Myst and the Masterpiece Edition, realMyst featured free-roaming, real-time 3D graphics instead of pre-rendered stills.[22] Weather effects like thunderstorms, sunsets, and sunrises were added to the Ages, and minor additions were made to the Ages to keep the game in sync with the story of the Myst novels and sequels. The game also added a new Age called Rime, which is featured in an extended ending.[22] realMyst was developed by Cyan, Inc. and Sunsoft, and published by Ubisoft. While the new interactivity of the game was praised, realMyst ran extremely slowly on most computers of the time.[23]

[edit] Handheld versions

In November 2005, Midway Games announced that they would be developing a remake of Myst for the PlayStation Portable. The remake would include additional content that was not featured in the original Myst, including the Rime age that was earlier seen in realMyst. [24] The game was released in Japan and Europe in 2006, and the U.S. version was released in 2008.[2]

A version of Myst for the Nintendo DS was also released in December 2007. The version features re-mastered video and audio, using source code specifically re-written for the Nintendo DS. The remake features Rime as a playable Age, with an all new graphic set.[3] Myst DS was released in North America on May 13, 2008.

In August 2008, Cyan announced that the company was developing a version of Myst for the Apple iPhone, internally dubbed "iMyst".[25]

[edit] Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

Myst was a very popular and commercially successful game. Along with The 7th Guest, it was widely regarded as a killer application that accelerated the sales of CD-ROM drives.[18][33] The game's success also led to a number of games which sought to copy Myst's success, named "Myst clones".[18] Myst was the bestselling PC game throughout the 1990s, until The Sims exceeded its sales in 2002.[5] The PC version of Myst holds an average score of 90% at Game Rankings based on six reviews,[26] although the subsequent remakes of the game and the console ports have generally received lower average scores. Myst's success baffled some who wondered how a game some saw as "little more than 'an interactive slide show'" turned out to be a hit.[34]

Myst was generally praised by critics. Wired Magazine and The New York Times suggested that Myst was evidence that video games could in fact evolve into an art form.[35] Entertainment Weekly reported that some players considered Myst's "virtual morality" a religious experience.[36] Aarhus University professor Søren Pold pointed to Myst as an excellent example of how stories can be told using objects rather than people.[37] Laura Evenson, writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, pointed to adult-oriented games like Myst as evidence the video game industry was emerging from its "adolescent" phase.[38]

GameSpot said that "Myst is an immersive experience that draws you in and won't let you go."[32] Writing about Myst's reception, Greg M. Smith noted that Myst had become a hit and was regarded as incredibly immersive despite most closely resembling "the hoary technology of the slide show (with accompanying music and effects)".[10] Smith concluded that "Myst's primary brilliance lies in the way it provides narrative justification for the very things that are most annoying" about the technological constraints imposed on the game;[10] for instance, MacWorld praised Myst's designers for overcoming the occasionally debilitating slowness of CD drives to deliver a consistent experience throughout the game.[39] The publication went on to declare Myst the best game of 1994, stating that Myst removed the "most annoying parts of adventure games — vocabularies that [you] don't understand, people you can't talk to, wrong moves that get you killed and make you start over. You try to unravel the enigma of the island by exploring the island, but there's no time pressure to distract you, no arbitrary punishments put in your way".[40]

Some aspects of the game still received criticism. Several publications did not agree with the positive reception of the story; Jeremy Parrish of 1UP.com noted that while Myst's lack of interaction and continual plot suited the game, it helped usher in the death of the adventure game genre.[18] Edge stated the main flaw with the game was that the game engine was nowhere near as sophisticated as the graphics.[31] Heidi Fournier of Adventure Gamers noted a few critics complained about the difficulty and lack of context of the puzzles, while others believed these elements added to the gameplay.[30] Similarly, critics were split on whether the lack of a plot the player could actually change was a good or bad element.[41] In a 2000 retrospective review, IGN declared that Myst had not aged well and that playing it "was like watching hit TV shows from the 70s. 'People watched that?,' you wonder in horror."[33]

[edit] Legacy

In addition to the numerous remakes and ports of the game, Myst's success led to several sequels. Riven was released on October 29, 1997, and explains how the Stranger came upon the Myst book in the first game. Myst III: Exile was released simultaneously for Macintosh and Windows systems in North America on May 7, 2001, and was later ported to the PlayStation 2 and Xbox consoles. Exile was not developed by Cyan; Presto Studios developed the title and Ubisoft published it.[42] Taking place 10 years after the events of Riven, Exile reveals the reasons for Atrus' sons being imprisoned and the disastrous effects their greed caused.[43] The fourth entry in the series, Myst IV: Revelation, was released on September 10, 2004 and was developed and published entirely by Ubisoft. The music was composed by Jack Wall with assistance from Peter Gabriel.[44] The final game in the Myst saga was Myst V: End of Ages, developed by Cyan Worlds and released on September 19, 2005.[45]

In addition to the main Myst saga, Cyan developed Uru: Ages Beyond Myst, which was released on November 14, 2003.[46] Uru allows players to customize their avatars, and renders graphics in real-time. The multiplayer component of Uru was initially cancelled, but Gametap eventually revived it as Myst Online: Uru Live on February 15, 2007. On February 4, 2008, Gametap Creative Director Ricardo Sanchez announced that the game was cancelled, and that the servers would be shut down 60 days after the announcement.[47] The Miller brothers collaborated with David Wingrove and wrote several novels based on the Myst universe, which were published by Hyperion. The novels, entitled Myst: The Book of Atrus, Myst: The Book of Ti'ana, and Myst: The Book of D'ni, fill in the games' backstory and were packaged together as The Myst Reader.

As of November 27, 2007, the Myst franchise has sold over 12 million copies worldwide,[48] with Myst representing more than six million copies in the figure.[49] The game's popularity has led to several mentions in popular culture. References to Myst made appearances in an episode of the The Simpsons (Treehouse of Horror VI),[50] and Matt Damon wanted The Bourne Conspiracy to be a puzzle game like Myst, refusing to lend his voice talent to the game when it was turned into a shooter instead.[51] Myst has also been used for educational and scientific purposes; Becta recognized a Primary school teacher, Tim Rylands, who had made literacy gains using Myst as a teaching tool,[52] and researchers have used the game for studies examining the effect of video games on aggression.[53]

[edit] References

- ^ "Myst for Macintosh". MobyGames. http://www.mobygames.com/game/macintosh/myst. Retrieved on 2008-04-24.

- ^ a b c "Myst (PSP)". IGN. http://psp.ign.com/objects/786/786203.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-12.

- ^ a b Purchese, Rob (2007-06-07). "Myst heads to DS". Eurogamer. http://www.eurogamer.net/article.php?article_id=77459. Retrieved on 2007-06-07.

- ^ Staff (2008-03-31). "Empire Interactive's Myst DS Goes Gold". IGN. http://ds.ign.com/articles/863/863215p1.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-22.

- ^ a b Walker, Trey (2002-03-22). "The Sims overtakes Myst". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/pc/strategy/simslivinlarge/news_2857556.html. Retrieved on 2008-03-17.

- ^ Cyan, Inc. (1993). Myst User Manual. "Manipulating Objects" (Windows version ed.). Brøderbund. pp. 5–6.

- ^ Cyan, Inc. (1993). Myst User Manual. "Zip Mode" (Windows version ed.). Brøderbund. pp. 9.

- ^ Cyan, Inc. (1993). Myst User Manual. "Options Menu" (Windows version ed.). Brøderbund. pp. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f Carroll, John (August 1994). "Guerrillas in the Myst". Wired Magazine 2 (8). http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/2.08/myst_pr.html.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Greg (2002). Hop on Pop: The Pleasures and Politics of Popular Culture. Navigating Myst-y Landscapes: Killer Applications and Hybrid Criticism. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822327376.

- ^ Cyan, Inc. (1993). Myst User Manual (Windows version ed.). Brøderbund. pp. 2.

- ^ a b Poole, Stephen. "Myst Game Guide". Gamespot. http://www.gamespot.com/features/myst_gg/index.html. Retrieved on 2009-02-08.

- ^ a b c Stern, Gloria (1994-08-23). "Through the Myst". WorldVillage.com. http://www2.worldvillage.com/wv/gamezone/html/reviews/myst.htm. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ^ Cyan, Inc. (1993). Myst User Manual. "About the Authors" (Windows version ed.). Brøderbund. pp. 15.

- ^ Miller, Rand and Robyn; Cyan. (1993). The Making of Myst (.MOV). Cyan, Inc./Brøderbund.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Miller Bros., Cyan, &c. (1993). The Making of Myst (.MOV). Cyan, Inc./Brøderbund.

- ^ Gillen, Marilyn (1994-07-09). "Interactive Gamers Try to Follow Enveloping 'Myst'". Billboard 1: 100.

- ^ a b c d Parrish, Jeremy. "When SCUMM Ruled the Earth". 1UP.com. http://www.1up.com/do/feature?cId=3134600. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ^ Thomas, David (1998-05-08). "Mastermind of Myst, Riven also has a talent for music". The Denver Post.

- ^ Gann, Patrick (1998). "Myst: The Soundtrack". RPGFan. http://www.rpgfan.com/soundtracks/myst/index.html. Retrieved on 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Myst: Masterpiece Edition". Ubisoft. 2000. http://www.ubi.com/US/Games/Info.aspx?pId=196. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ^ a b Walker, Trey (2000-10-20). "Real Myst Shipping in Early November". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/pc/adventure/realmyst/news.html?sid=2643165&mode=recent. Retrieved on 2008-05-07.

- ^ Staff (2000-11-13). "RealMyst Review". IGN. http://pc.ign.com/articles/165/165612p1.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-29.

- ^ Staff (2005-11-22). "Myst Set for PSP". IGN. http://psp.ign.com/articles/670/670041p1.html. Retrieved on 2006-03-29.

- ^ Cohen, Peter (2008-08-18). "Myst coming to iPhone". Macworld. http://www.macworld.com/article/135131/2008/08/myst.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-26.

- ^ a b "Myst - PC". Game Rankings. http://www.gamerankings.com/htmlpages2/89467.asp?q=Myst. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ^ "Real Myst Reviews". Game Rankings. http://www.gamerankings.com/htmlpages2/430806.asp. Retrieved on 2008-04-08.

- ^ "Myst (PSP) Reviews". Game Rankings. http://www.gamerankings.com/htmlpages2/930989.asp?q=myst. Retrieved on 2008-05-01.

- ^ "Myst (DS) Reviews". Game Rankings. http://www.gamerankings.com/htmlpages2/939943.asp?q=myst. Retrieved on 2008-04-08.

- ^ a b Fournier , Heidi (2002-05-20). "Myst: Review". Adventure Gamers. http://www.adventuregamers.com/display.php?id=52. Retrieved on 2008-04-29.

- ^ a b "Myst Review (Mac)". Edge (Future Publishing): p. 66. January 1994 (Issue 4).

- ^ a b Sengstack, Jeff (1996-05-01). "Myst for PC Review". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/pc/adventure/myst/review.html. Retrieved on 2008-03-05.

- ^ a b Staff (2000-08-01). "RC Retroview: Myst". IGN. http://pc.ign.com/articles/082/082913p1.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-21.

- ^ Miller, Laura (1997-11-06). "Riven Rapt". Salon. http://archive.salon.com/21st/feature/1997/11/cov_06riven.html. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (1994-12-04). "A New Art Form May Arise From the 'Myst'". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F07E7DD1030F937A35751C1A962958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=1. Retrieved on 2008-03-12.

- ^ Daly, Steve (1994-10-07). "The Land of 'Myst' Opportunity". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,303937,00.html. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ^ Pold, Søren. "Writing With the Code - a Digital Poetics". University of Aarhus. http://imv.au.dk/~pold/publikat/writcode.htm. Retrieved on 2008-04-15.

- ^ Evenson, Laura (1994-12-22). "Interactive CD-ROMs come of age". San Francisco Chronicle. p. DAT36.

- ^ Beekman, George and Ben (March 1994). "Myst 1.0". MacWorld: 76.

- ^ Levy, Steven (January 1995). "1994 Macintosh Game Hall of Fame". MacWorld (1): 100–106.

- ^ Smith, Andy (March 1998). "Amiga Reviews Myst". Amiga Format (108): 35–37. http://amigareviews.classicgaming.gamespy.com/myst.htm.

- ^ Staff (2001-04-05). "News Briefs: Halo rumors fly, Tribes 2 event on Saturday, and no TF2 at E3?". IGN. http://pc.ign.com/articles/093/093192p1.html. Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- ^ Staff (2001-05-02). "New Myst III Trailer". IGN. http://pc.ign.com/articles/094/094134p1.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-12.

- ^ Castro, Juan (2004-04-05). "Myst IV Announced". IGN. http://pc.ign.com/articles/504/504216p1.html. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- ^ Surrette, Tim (2005-01-12). "Myst V landing on PCs this fall". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/pc/adventure/mystvendofages/news.html?sid=6116222&mode=all. Retrieved on 2008-05-01.

- ^ Calvert, Justin (2003-11-14). "Uru: Ages Beyond Myst ships". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/pc/adventure/uruonlineagesbeyondmyst/news.html?sid=6083553. Retrieved on 2008-04-19.

- ^ Onyett, Charlie (2008-02-04). "Myst Online: Uru Live is Discontinued". IGN. http://pc.ign.com/articles/849/849518p1.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-09.

- ^ Empire Interactive (2007-11-27). Silverstar's Empire Interactive Introduces Myst Nintendo DS for North America. Press release.

- ^ Guilofil, Michael (2001-05-22). "Beyond the Myst". The Spokesman-Review. http://www.spokesmanreview.com/pf.asp?date=052201&id=s966647.

- ^ Basner, David (2000-05-04). "The Simpsons" as Fart, D'oh!, Art". The Simpsons Archive. http://snpp.com/other/papers/db.paper.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-01.

- ^ Klepeck, Patrick (2008-04-29). "Update: Matt Damon Didn’t Speak Directly To ‘Bourne’ Developers, Wanted A Game Like ‘Myst’". MTV. http://multiplayerblog.mtv.com/2008/04/29/matt-damon-never-spoke-with-bourne-developers-wanted-a-game-like-myst/. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ^ Twist, Jo (2005-08-25). "Pupils learn through Myst game". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4160466.stm. Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- ^ Kirsh SJ (1998). "Seeing the world through Mortal Kombat-colored glasses: violent video games and the development of a short-term hostile attribution bias". Childhood 5 (5): 177–184. doi:.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Myst |

- realMyst website

- Myst at MobyGames

- Myst at the Internet Movie Database

- Myst at MYSTerium

|

||||||||||||||||