Vladimir Mayakovsky

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (Влади́мир Влади́мирович Маяко́вский) (July 19 [O.S. July 7] 1893 – April 14, 1930) was a Russian poet and playwright, among the foremost representatives of early-20th century Russian Futurism.

Contents |

[edit] Early life

He was born the last of three children in Baghdati, Georgia where his father worked as a forest ranger. His father was of Ukrainian Cossack[1] descent and his mother was of Ukrainian descent. Although Mayakovsky spoke Georgian at school and with friends, his family spoke primarily Russian at home. At the age of 14 Mayakovsky took part in socialist demonstrations at the town of Kutaisi, where he attended the local grammar school. After the sudden and premature death of his father in 1906, the family — Mayakovsky, his mother, and his two sisters — moved to Moscow, where he attended School No. 5.

In Moscow, Mayakovsky developed a passion for Marxist literature and took part in numerous activities of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party; he was to later become an RSDLP (Bolshevik) member. In 1908, he was dismissed from the grammar school because his mother was no longer able to afford the tuition fees.

Around this time, Mayakovsky was imprisoned on three occasions for subversive political activities but, being underage, he avoided transportation. During a period of solitary confinement in Butyrka prison in 1909, he began to write poetry, but his poems were confiscated. On his release from prison, he continued working within the socialist movement, and in 1911 he joined the Moscow Art School where he became acquainted with members of the Russian Futurist movement. He became a leading spokesman for the group Gileas (Гилея), and a close friend of David Burlyuk, whom he saw as his mentor.

[edit] Literary life

The 1912 Futurist publication A Slap in the Face of Public Taste (Пощёчина общественному вкусу) contained Mayakovsky's first published poems: "Night" (Ночь) and "Morning" (Утро). Because of their political activities, Burlyuk and Mayakovsky were expelled from the Moscow Art School in 1914.

His work continued in the Futurist vein until 1914. His artistic development then shifted increasingly in the direction of narrative and it was this work, published during the period immediately preceding the Russian Revolution, which was to establish his reputation as a poet in Russia and abroad.

A Cloud in Trousers (1915) was Mayakovsky's first major poem of appreciable length and it depicted the heated subjects of love, revolution, religion and art, written from the vantage point of a spurned lover. The language of the work was the language of the streets, and Mayakovsky went to considerable lengths to debunk idealistic and romanticised notions of poetry and poets.

| Your thoughts, dreaming on a softened brain, Of Grandfatherly gentleness I'm devoid, |

Вашу мысль У меня в душе ни одного седого волоса, |

(From the prologue of A Cloud in Trousers.)

In the summer of 1915, Mayakovsky fell in love with a married woman, Lilya Brik, and it is to her that the poem "The Backbone Flute" (1916) was dedicated; unfortunately for Mayakovsky, she was the wife of his publisher, Osip Brik. The love affair, as well as his impressions of war and revolution, strongly influenced his works of these years. The poem "War and the World" (1916) addressed the horrors of WWI and "Man" (1917) is a poem dealing with the anguish of love.

Mayakovsky was rejected as a volunteer at the beginning of WWI, and during 1915-1917 worked at the Petrograd Military Automobile School as a draftsman. At the onset of the Russian Revolution, Mayakovsky was in Smolny, Petrograd. There he witnessed the October Revolution. He started reciting poems such as "Left March! For the Red Marines: 1918" (Левый марш (Матросам), 1918) at naval theatres, with sailors as an audience.

His satirical play Mystery-Bouffe was staged in 1918, and again, more successfully, in 1921.

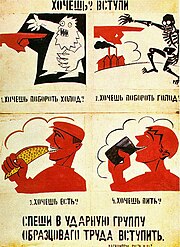

After moving back to Moscow, Mayakovsky worked for the Russian State Telegraph Agency (ROSTA) creating — both graphic and text — satirical Agitprop posters. In 1919, he published his first collection of poems Collected Works 1909-1919 (Все сочиненное Владимиром Маяковским). In the cultural climate of the early Soviet Union, his popularity grew rapidly. During 1922-1928, Mayakovsky was a prominent member of the Left Art Front and went on to define his work as 'Communist futurism' (комфут). He edited, along with Sergei Tretyakov and Osip Brik, the journal LEF.

As one of the few Soviet writers who were allowed to travel freely, his voyages to Latvia, Britain, Germany, the United States, Mexico and Cuba influenced works like My Discovery of America (Мое открытие Америки, 1925). He also travelled extensively throughout the Soviet Union.

On a lecture tour in the United States, Mayakovsky met Elli Jones, who later gave birth to his daughter, an event which Mayakovsky only came to know in 1929, when the couple met clandestinely in the south of France, as the relationship was kept secret. In the late 1920s, Mayakovsky fell in love with Tatiana Yakovleva and to her he dedicated the poem "A Letter to Tatiana Yakovleva" (Письмо Татьяне Яковлевой, 1928).

The relevance of Mayakovsky's influence cannot be limited to Soviet poetry. While for years he was considered the Soviet poet par excellence, he also changed the perceptions of poetry in wider 20th century culture. His political activism as a propagandistic agitator was rarely understood and often looked upon unfavourably by contemporaries, even close friends like Boris Pasternak. Near the end of the 1920s, Mayakovsky became increasingly disillusioned with the course the Soviet Union was taking under Joseph Stalin: his satirical plays The Bedbug (Клоп, 1929) and The Bathhouse (Баня, 1930), which deal with the Soviet philistinism and bureaucracy, illustrate this development.

On the evening of April 14, 1930, Mayakovsky shot himself. The unfinished poem in his suicide note read, in part:

| So to say - "the incident dissolved" |

Mayakovsky was interred at the Moscow Novodevichy Cemetery.

[edit] After his death

In 1930, his birthplace of Bagdadi in Georgia was renamed Mayakovsky in his honour. Following Stalin's death, rumours arose that Mayakovsky did not commit suicide but was in fact murdered at the behest of Stalin; there is, however, no evidence that he was murdered. During the 1990s, as KGB files were being declassified, there was hope that new evidence would come to light on this question, but none has been found and the hypothesis remains unproven.

After his death, Mayakovsky was attacked in the Soviet press as a "formalist" and a "fellow-traveller" (попутчик) (as opposed to officially recognised "proletarian poets", such as Demyan Bedny). When, in 1935, Lilya Brik wrote to Stalin about this, Stalin wrote a comment on Brik's letter:

"Comrade Yezhov, please take charge of Brik's letter. Mayakovsky is still the best and the most talented poet of our Soviet epoch. Indifference to his cultural heritage is a crime. Brik's complaints are, in my opinion, justified..." (Source: Memoirs by Vasily Katanyan (L. Yu. Brik's stepson) p.112)

These words became a cliché and officially canonized Mayakovsky but, as Boris Pasternak noted,[2] they "dealt him the second death" in some circles.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko once said As a poet, I wanted to mix something from Mayakovsky and Yesenin.[3] Mayakovsky was, however, the most influential futurist in Lithuania and his poetry helped to form the Four Winds movement there.[4] He was also an influence on the writer Valentin Kataev. Andrey Voznesensky called Mayakovsky teacher and favorite poet[5] and dedicated him a poem Маяковский в Париже (Mayakovsky in Paris). [6]. In 1967 the Taganka Theater staged the poetical performance Послушайте!, based on Mayakovsky's works. Role of the poet was played by Vladimir Vysotsky, who also was inspired by Mayakovsky's poetry[7].

In 1974 a Russian State Museum of Mayakovsky was opened in the center of Moscow in the building where Mayakovsky resided from 1919 to 1930[8].

Frank O'Hara wrote a poem named after him, "Mayakovsky" in which the speaker is standing in a bathtub, a probable reference to his play "The Bathhouse."

In 1986 English singer and songwriter Billy Bragg recorded the album Talking with the Taxman about Poetry, named after a namesake Mayakovsky's poem.

In 1991, City Lights published Listen! Early Poems, a collection translated by Maria Enzensberger.

The well-known phrase "Lenin lives, lived and will live" come from his elegy "Vladimir Ilyich Lenin".

[edit] References

- ^ http://az.lib.ru/m/majakowskij_w_w/text_0212.shtml

- ^ http://www.russ.ru/krug/20030723_ls.html

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://www.tekstai.lt/tekstai/4vejai/apie/nyliunas.htm

- ^ http://www.ogoniok.com/archive/2002/4734/08-08-11/

- ^ http://www.ruthenia.ru/60s/voznes/antimir/mayakovskij.htm

- ^ http://taganka.theatre.ru/press/articles/5392/

- ^ http://www.mayakovsky.info/museum.html

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir (Patricia Blake ed., trans. Max Hayward and George Reavey). The bedbug and selected poetry. (Meridian Books, Cleveland, 1960).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. Mayakovsky: Plays. Trans. Guy Daniels. (Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Il, 1995). ISBN 0810113392.

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. For the voice (The British Library, London, 2000).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir (ed. Bengt Jangfeldt, trans. Julian Graffy). Love is the heart of everything : correspondence between Vladimir Mayakovsky and Lili Brik 1915-1930 (Polygon Books, Edinburgh, 1986).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir (comp. and trans. Herbert Marshall). Mayakovsky and his poetry (Current Book House, Bombay, 1955).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. Selected works in three volumes (Raduga, Moscow, 1985).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. Selected poetry. (Foreign Languages, Moscow, 1975).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir (ed. Bengt Jangfeldt and Nils Ake Nilsson). Vladimir Majakovsky: Memoirs and essays (Almqvist & Wiksell Int., Stockholm 1975).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. Satira ('Khudozh. lit.,' Moscow, 1969).

- Brown, E. J. Mayakovsky: a poet in the revolution (Princeton Univ. Press, 1973).

- Jangfeldt, Bengt. Majakovsky and futurism 1917-1921 (Almqvist & Wiksell International, Stockholm, 1976).

- Stapanian, Juliette. Mayakovsky's cubo-futurist vision (Rice University Press, 1986).

- Charters, Ann & Samuel. I love : the story of Vladimir Mayakovsky and Lili Brik (Farrar Straus Giroux, NY, 1979).

- Lavrin, Janko. From Pushkin to Mayakovsky, a study in the evolution of a literature. (Sylvan Press, London, 1948).

- Mikhailov, Aleksandr Alekseevich. Maiakovskii (Mol. gvardiia, Moscow, 1988).

- Terras, Victor. Vladimir Mayakovsky (Twayne, Boston, 1983).

- Vallejo, César (trans. Richard Schaaf) The Mayakovsky case (Curbstone Press, Willimantic, CT, 1982).

- Wachtel, Michael. The development of Russian verse : meter and its meanings (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- Humesky, Assya. Majakovskiy and his neologisms (Rausen Publishers, NY, 1964).

- Shklovskii, Viktor Borisovich. (ed. and trans. Lily Feiler). Mayakovsky and his circle (Dodd, Mead, NY, 1972).

- Novatorskoe iskusstvo Vladimira Maiakovskogo (trans. Alex Miller). Vladimir Mayakovsky: Innovator (Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1976).

- Rougle, Charles. Three Russians consider America : America in the works of Maksim Gorkij, Aleksandr Blok, and Vladimir Majakovsky (Almqvist & Wiksell International, Stockholm, 1976).

- Aizlewood, Robin. Verse form and meaning in the poetry of Vladimir Maiakovsky: Tragediia, Oblako v shtanakh, Fleita-pozvonochnik, Chelovek, Liubliu, Pro eto (Modern Humanities Research Association, London, 1989).

- Noyes, George R. Masterpieces of the Russian drama (Dover Pub., NY, 1960).

- (Lithuanian) Nyka-Niliūnas, Alfonsas. Keturi vėjai ir keturvėjinikai (The Four Winds literary movement and its members), Aidai, 1949, No. 24.

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Vladimir Mayakovsky |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Vladimir Mayakovsky |

- Biography

- State Museum of Mayakovsky in Moscow (Russian/English)

- Audio introduction, in English, to Mayakovsky's poems. Includes links.

- Between Agitation and Animation: Activism and Participation in Twentieth Century Art by Stella Rollig

- Radio Mayakovsky More than 100 new songs written to the Mayakovsky verses. Mayakovsky Voice, Verses Readers and other stuff

- Vladimir Mayakovsky's Gravesite

- "Баня" ("The Bathhouse"): Mayakovsky and Meyerhold)

- Meyerhold & Mayakovsky - Biomechanics & the Communist Utopia

- The 'raging bull' of Russian poetry article by Dalia Karpel at Haaretz.com, published on-line July 5, 2007

- Archival film edited by Copernicus Films

- "Take that!" ("Нате!") English translation by Dina Belyayeva published online 12.12.2008

- "So Could You?" ("А вы могли бы?") English translation by Dina Belyayeva published online 12.11.2008

- "The love boat smashed against reality..." ("Любовная лодка разбилась о быт") English translation by Dina Belyayeva published online 12.11.2008