Matrix multiplication

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In mathematics, matrix multiplication is the operation of multiplying a matrix with either a scalar or another matrix. This article gives an overview of the various ways to perform matrix multiplication.

Contents |

[edit] Ordinary matrix product

This is the most often used and most important way to multiply matrices. It is defined between two matrices only if the number of columns of the first matrix is the same as the number of rows of the second matrix.

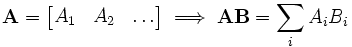

Formally, for

,

,

then

where the elements of A.B are given by

for each pair i and j with 1 ≤ i ≤ m and 1 ≤ j ≤ p. The algebraic system of "matrix units" summarises the abstract properties of this kind of multiplication.

[edit] Calculating directly from the definition

The picture to the left shows how to calculate the (1,2) element and the (3,3) element of AB if A is a 3×2 matrix, and B is a 2×3 matrix. Elements from each matrix are paired off in the direction of the arrows; each pair is multiplied and the products are added. The location of the resulting number in AB corresponds to the row and column that were considered.

For example BA:

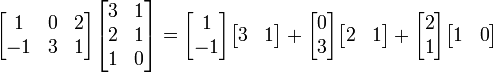

[edit] The coefficients-vectors method

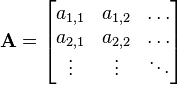

This matrix multiplication can also be considered from a slightly different viewpoint: it adds vectors together after being multiplied by different coefficients. If A and B are matrices given by:

and

and

then

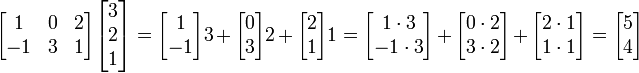

The example revisited:

The rows in the matrix on the left can be thought of as the list of coefficients and the matrix on the right as the list of vectors. In the example, the first row is [1 0 2], and thus we take 1 times the first vector, 0 times the second vector, and 2 times the third vector.

The equation can be simplified further by using outer products:

The terms of this sum are matrices of the same shape, each describing the effect of one column of A and one row of B on the result. The columns of A can be seen as a coordinate system of the transform, i.e. given a vector x we have  where xi are coordinates along the Ai "axes". The terms AiBi are like Aixi, except that Bi contains the ith coordinate for each column vector of B, each of which is transformed independently in parallel.

where xi are coordinates along the Ai "axes". The terms AiBi are like Aixi, except that Bi contains the ith coordinate for each column vector of B, each of which is transformed independently in parallel.

The example revisited:

The vectors  and

and  have been transformed to

have been transformed to  and

and  in parallel. One could also transform them one by one with the same steps:

in parallel. One could also transform them one by one with the same steps:

[edit] Vector-lists method

The ordinary matrix product can be thought of as a dot product of a column-list of vectors and a row-list of vectors. If A and B are matrices given by:

and

and

where

- A1 is the row vector of all elements of the form a1,x A2 is the row vector of all elements of the form a2,x etc,

- and B1 is the column vector of all elements of the form bx,1 B2 is the column vector of all elements of the form bx,2 etc,

then

In other words,  is the dot product of the Xth row vector of A and the Yth column vector of B.

is the dot product of the Xth row vector of A and the Yth column vector of B.

[edit] Properties

- Matrix multiplication is not generally commutative

- If A and B are both n x n matrices, then the determinants of their product is equal, regardless of order.

- det(AB) = det(BA)

- If both matrices are diagonal square matrices of the same dimension, their product is commutative.[1]

- If A is a matrix representative of a linear transformation L and B is a matrix representative of a linear transformation P then AB is a matrix representative of a linear transform P followed by the linear transformation L.

- Matrix multiplication is associative:

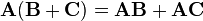

- Matrix multiplication is distributive:

.

.

- If the matrix is defined over a field (for example, over the Real or Complex fields), then it is compatible with scalar multiplication in that field.

- where c is a scalar.

[edit] Algorithms for efficient matrix multiplication

The complexity of matrix multiplication, if carried out naively, is O(n3), but more efficient algorithms do exist. Strassen's algorithm, devised by Volker Strassen in 1969 and often referred to as "fast matrix multiplication", is based on a clever way of multiplying two 2 × 2 matrices which requires only 7 multiplications (instead of the usual 8), at the expense of several additional addition and subtraction operations. Applying this trick recursively gives an algorithm with a multiplicative cost of  . Strassen's algorithm is awkward to implement, compared to the naive algorithm, and it lacks numerical stability. Nevertheless, it is beginning to appear in libraries such as BLAS, where it is computationally interesting for matrices with dimensions n > 100 (Press 2007, p. 108), and is very useful for large matrices over exact domains such as finite fields, where numerical stability is not an issue.

. Strassen's algorithm is awkward to implement, compared to the naive algorithm, and it lacks numerical stability. Nevertheless, it is beginning to appear in libraries such as BLAS, where it is computationally interesting for matrices with dimensions n > 100 (Press 2007, p. 108), and is very useful for large matrices over exact domains such as finite fields, where numerical stability is not an issue.

The algorithm with the lowest known exponent, which was presented by Don Coppersmith and Shmuel Winograd in 1990, has an asymptotic complexity of O(n2.376). It is similar to Strassen's algorithm: a clever way is devised for multiplying two k × k matrices with fewer than k3 multiplications, and this technique is applied recursively. It improves on the constant factor in Strassen's algorithm, reducing it to 4.537. However, the constant term implied in the O(n2.376) result is so large that the Coppersmith–Winograd algorithm is only worthwhile for matrices that are too big to handle on present-day computers (Knuth, 1998).

Since any algorithm for multiplying two n × n matrices has to process all 2 × n² entries, there is an asymptotic lower bound of ω(n2) operations. Raz (2002) proves a lower bound of Ω(m2logm) for bounded coefficient arithmetic circuits over the real or complex numbers.

Cohn et al. (2003, 2005) put methods, such as the Strassen and Coppersmith–Winograd algorithms, in an entirely different group-theoretic context. They show that if families of wreath products of Abelian with symmetric groups satisfying certain conditions exists, matrix multiplication algorithms with essential quadratic complexity exist. Most researchers believe that this is indeed the case (Robinson, 2005).

Because of the nature of Matrix operations and the layout of Matrices in memory, it is typically possible to gain substantial performance gains through use of parallelisation and vectorisation. It should therefore be noted that some lower time-complexity algorithms on paper may have indirect time complexity costs on real machines.

[edit] Relationship to linear transformations

Matrices offer a concise way of representing linear transformations between vector spaces, and (ordinary) matrix multiplication corresponds to the composition of linear transformations. This will be illustrated here by means of an example using three vector spaces of specific dimensions, but the correspondence applies equally to any other choice of dimensions.

Let X, Y, and Z be three vector spaces, with dimensions 4, 2, and 3, respectively, all over the same field, for example the real numbers. The coordinates of a point in X will be denoted as xi, for i = 1 to 4, and analogously for the other two spaces.

Two linear transformations are given: one from Y to X, which can be expressed by the system of linear equations

and one from Z to Y, expressed by the system

These two transformations can be composed to obtain a transformation from Z to X. By substituting, in the first system, the right-hand sides of the equations of the second system for their corresponding left-hand sides, the xi can be expressed in terms of the zk:

These three systems can be written equivalently in matrix–vector notation – thereby reducing each system to a single equation – as follows:

Representing these three equations symbolically and more concisely as

inspection of the entries of matrix C reveals that C = AB.

This can be used to formulate a more abstract definition of matrix multiplication, given the special case of matrix–vector multiplication: the product AB of matrices A and B is the matrix C such that for all vectors z of the appropriate shape Cz = A(Bz).

[edit] Scalar multiplication

The scalar multiplication of a matrix A = (aij) and a scalar r gives a product r A of the same size as A. The entries of r A are given by

For example, if

then

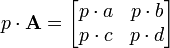

If we are concerned with matrices over a more general ring, then the above multiplication is the left multiplication of the matrix A with scalar p while the right multiplication is defined to be

When the underlying ring is commutative, for example, the real or complex number field, the two multiplications are the same. However, if the ring is not commutative, such as the quaternions, they may be different. For example

[edit] Hadamard product

For two matrices of the same dimensions, we have the Hadamard product (named after French mathematician Jaques Hadamard), also known as the entrywise product and the Schur product.[2]

Formally, for

,

,

then

where the elements of  are given by

are given by

Note that the Hadamard product is a submatrix of the Kronecker product.

The Hadamard product is commutative.

The Hadamard product appears in lossy compression algorithms such as JPEG.

[edit] Kronecker product

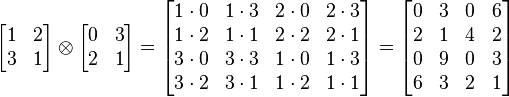

For any two arbitrary matrices A and B, we have the direct product or Kronecker product A ⊗ B defined as

If A is an m-by-n matrix and B is a p-by-q matrix, then their Kronecker product A ⊗ B is an mp-by-nq matrix.

The Kronecker product is not commutative.

For example

.

.

If A and B represent linear transformations V1 → W1 and V2 → W2, respectively, then A ⊗ B represents the tensor product of the two maps, V1 ⊗ V2 → W1 ⊗ W2.

[edit] Common properties

| The Wikibook The Book of Mathematical Proofs has a page on the topic of |

If A, B and C are matrices with appropriate dimensions defined over a commutative Field (e.g.  where c is a scalar in that field, then for all three types of multiplication:

where c is a scalar in that field, then for all three types of multiplication:

- Matrix multiplication is associative:

- Matrix multiplication is distributive:

.

.

- Matrix multiplication compatible with scalar multiplication:

[edit] Frobenius inner product

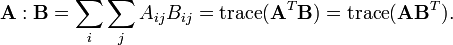

The Frobenius inner product, sometimes denoted A:B is the component-wise inner product of two matrices as though they are vectors. In other words, it is the sum of the entries of the Hadamard product, that is,

This inner product induces the Frobenius norm.

[edit] Powers of matrices

Square matrices can be multiplied by themselves repeatedly in the same way that ordinary numbers can. This repeated multiplication can be described as a power of the matrix. Using the ordinary notion of matrix multiplication, the following identities hold for an n-by-n matrix A, a positive integer k, and a scalar c:

The naive computation of matrix powers is to multiply k times the matrix A to the result, starting with the identity matrix just like the scalar case. This can be improved using the binary representation of k, a method commonly used to scalars. An even better method is to use the eigenvalue decomposition of A.

Calculating high powers of matrices can be very time-consuming, but the complexity of the calculation can be dramatically decreased by using the Cayley-Hamilton theorem, which takes advantage of an identity found using the matrices' characteristic polynomial and gives a much more effective equation for Ak, which instead raises a scalar to the required power, rather than a matrix.

[edit] See also

- Cracovian (for another matrix product)

- Strassen algorithm (1969)

- Winograd algorithm (1980)

- Coppersmith–Winograd algorithm (1990)

- Logical matrix

- Matrix chain multiplication

- Matrix inversion

- Composition of relations

- Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms

- Matrix addition

- Dot product

[edit] Notes

- ^ Matrix Multiplication

- ^ (Horn & Johnson 1985, Ch. 5).

[edit] References

- Henry Cohn, Robert Kleinberg, Balazs Szegedy, and Chris Umans. Group-theoretic Algorithms for Matrix Multiplication. arΧiv:math.GR/0511460. Proceedings of the 46th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 23-25 October 2005, Pittsburgh, PA, IEEE Computer Society, pp. 379–388.

- Henry Cohn, Chris Umans. A Group-theoretic Approach to Fast Matrix Multiplication. arΧiv:math.GR/0307321. Proceedings of the 44th Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 11-14 October 2003, Cambridge, MA, IEEE Computer Society, pp. 438–449.

- Coppersmith, D., Winograd S., Matrix multiplication via arithmetic progressions, J. Symbolic Comput. 9, p. 251-280, 1990.

- Horn, Roger A.; Johnson, Charles R. (1985), Matrix Analysis, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-38632-6

- Knuth, D.E., The Art of Computer Programming Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms. Third Edition, 1998. pp 501.

- Press, William H.; Flannery, Brian P.; Teukolsky, Saul A.; Vetterling, William T. (2007), Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8.

- Ran Raz. On the complexity of matrix product. In Proceedings of the thirty-fourth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing. ACM Press, 2002. doi:10.1145/509907.509932.

- Robinson, Sara, Toward an Optimal Algorithm for Matrix Multiplication, SIAM News 38(9), November 2005. PDF

- Strassen, Volker, Gaussian Elimination is not Optimal, Numer. Math. 13, p. 354-356, 1969.

[edit] External links

| The Wikibook Applicable Mathematics has a page on the topic of |

- The Simultaneous Triple Product Property and Group-theoretic Results for the Exponent of Matrix Multiplication

- WIMS Online Matrix Multiplier

- Matrix Multiplication Problems

- Matrix Multiplication in C

- Linear algebra: matrix operations Multiply or add matrices of a type and with coefficients you choose and see how the result was computed.