Euler angles

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Euler angles were developed by Leonhard Euler to describe the orientation of a rigid body (a body in which the relative position of all its points is constant) in 3-dimensional Euclidean space. To give an object a specific orientation it may be subjected to a sequence of three rotations described by the Euler angles. This is equivalent to saying that a rotation matrix can be decomposed as a product of three elemental rotations.

Contents |

[edit] Definition

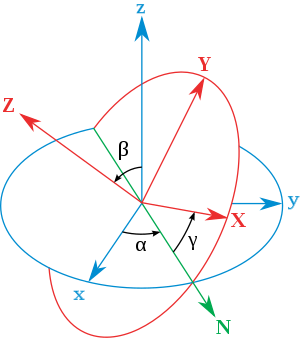

Euler angles are a means of representing the spatial orientation of any frame of the space as a composition of rotations from a reference frame. In the following the fixed system is denoted in lower case (x,y,z) and the rotated system is denoted in upper case letters (X,Y,Z).

The definition is Static. The intersection of the xy and the XY coordinate planes is called the line of nodes (N).

- α is the angle between the x-axis and the line of nodes.

- β is the angle between the z-axis and the Z-axis.

- γ is the angle between the line of nodes and the X-axis.

This previous definition is called z-x-z convention and is one of several common conventions; others are x-y-z and z-y-x. Unfortunately the order in which the angles are given and even the axes about which they are applied has never been “agreed” upon. When using Euler angles the order and the axes about which the rotations are applied should be supplied.[1]

Euler angles are one of several ways of specifying the relative orientation of two such coordinate systems. Moreover, different authors may use different sets of angles to describe these orientations, or different names for the same angles. Therefore a discussion employing Euler angles should always be preceded by their definition.

[edit] Angle ranges

- α and γ range are defined modulo 2π radians. A valid range could be [-π, π].

- β range is modulo π radians. For example could be [0, π] or [-π/2, π/2].

The angles α, β and γ are uniquely determined except for the singular case that the xy and the XY planes are identical, the z axis and the Z axis having the same or opposite directions. Indeed, if the z axis and the Z axis are the same, β = 0 and only (α+γ) is uniquely defined (not the individual values), and , similarly, if the z axis and the Z axis are opposite, β = π and only (α-γ) is uniquely defined (not the individual values). These ambiguities are known as gimbal lock in applications.

[edit] Relationship with physical motions

[edit] Euler rotations

Euler rotations are defined as the movement obtained by changing one of the Euler angles while leaving the other two constant. Euler rotations are never expressed in terms of the external frame, or in terms of the co-moving rotated body frame, but in a mixture. They constitute a mixed axes of rotation system, where the first angle moves the line of nodes around the external axis z, the second rotates around the line of nodes and the third one is an intrinsic rotation around an axis fixed in the body that moves.

These rotations are called Precession, Nutation, and intrinsic rotation. They satisfy the following remarkable property: Write the rotation about the given angles (φ,θ,ψ) as a composition

- A(φ,θ,ψ) = R(φ,θ,ψ)N(φ,θ)P(φ)

of a precession, a nutation and a rotation. Then, the following properties hold true

- A(δφ + φ,θ,ψ) = P(δφ)A(φ,θ,ψ)

- A(φ,δθ + θ,ψ) = N(φ,δθ)A(φ,θ,ψ)

- A(φ,δ,δψ + ψ) = R(φ,θ,δψ)A(φ,θ,ψ)

As consequence of this property, Euler rotations are commutative in the sense that given any frame, is the same to perform over it a precesion α followed by a nutation β, than to perform the nutation β followed by the precession α, as can be easily seen using the analogy of the gimbal. The same applies for any combination of the three rotations.

[edit] Matrix expression for Euler rotations

As a precession is equivalent to a rotation from the reference frame rotation, both are equivalent to a left-multiplication. We can perform a precession of a given frame 'F' with just the product R.F, where R is the rotation matrix for the angle we want to rotate. In a similar way, we can perform an intrinsic rotation with a right multiplication of the matrix of the frame. Nevertheless for nutation rotations we cannot use directly the matrix of the rotation we want to perform. We have to perform first a change of basis.

[edit] Euler angles as composition of Euler rotations

When these rotations are performed on a frame whose Euler angles are all zero, the rotating XYZ system starts coincident with the fixed xyz system. The first rotation is performed around z (which is parallel to Z), the second around the line of nodes N (which at this point is over X), and the third around Z.

If we suppose a set of frames, able to move each respect the former just one angle, like a gimbal, there will be one initial, one final and two in the middle, which are called intermediate frames.

[edit] Other composition of movements equivalent

Assumed some initial conditions, the former definition can be seen as composition of three rotations around the intrinsic (moving) or extrinsic (fixed) axes.

Given two coordinate systems xyz and XYZ with common origin, starting with the axis z and Z overlapping, the position of the second can be specified in terms of the first using three rotations with angles α, β, γ in three ways equivalent to the former definition, as follows:

- Moving axes of rotation (See Tait-Bryan angles) The XYZ system is fixed while the xyz system rotates. Starting with the xyz system coinciding with the XYZ system, the same rotations as before can be performed using only rotations around the moving axis.

- Rotate the xyz-system about the z-axis by α. The x-axis now lies on the line of nodes.

- Rotate the xyz-system again about the now rotated x-axis by β. The z-axis is now in its final orientation, and the X-axis remains on the line of nodes.

- Rotate the xyz-system a third time about the new z-axis by γ.

- Fixed axes of rotation - The xyz system is fixed while the XYZ system rotates. Start with the rotating XYZ system coinciding with the fixed xyz system.

- Rotate the XYZ-system about the z-axis by γ. The X-axis is now at angle γ with respect to the x-axis.

- Rotate the XYZ-system again about the x-axis by β. The Z-axis is now at angle β with respect to the z-axis.

- Rotate the XYZ-system a third time about the z-axis by α. The first and third axes are identical.

- Equivalence of the movements

The static description is usually used in conjunction with spherical trigonometry. It is the only form in older sources. The two rotating axes descriptions are usually used in conjunction with matrices, since 2D coordinate rotations have a simple form. These last two are equivalent, since rotation about a moved axis is the conjugation of the original rotation by the move in question.

To be explicit, in the fixed axes description, let x(φ) and z(φ) denote the rotations of angle φ about the x-axis and z-axis, respectively. In the moving axes description, let Z(φ)=z(φ), X′(φ) be the rotation of angle φ about the once-rotated X-axis, and let Z″(φ) be the rotation of angle φ about the twice-rotated Z-axis. Then:

- Z″(α)oX′(β)oZ(γ) = [ (X′(β)z(γ)) o z(α) o (X′(β)z(γ))−1 ] o X′(β) o z(γ)

-

-

- = [ {z(γ)x(β)z(−γ) z(γ)} o z(α) o {z(−γ) z(γ)x(−β)z(−γ)} ] o [ z(γ)x(β)z(−γ) ] o z(γ)

- = z(γ)x(β)z(α)x(−β)x(β) = z(γ)x(β)z(α) .

-

-

The equivalence of the static description with the rotating axes descriptions can be verified by direct geometric construction, or by showing that the nine direction cosines (between the three xyz axes and the three XYZ axes) form the correct rotation matrix.

The equivalence of the static description with the rotating axes descriptions can be understood as external or internal composition of matrices. Composing rotations about fixed axes is to multiply our orientation matrix by the left. Composing rotations about the moving axes is to multiply the orientation matrix by the right.

Both methods will lead to the same final decomposition. If M = A.B.C is the orientation matrix (the components of the frame to be described in the reference frame), it can be reached from composing C, B and A at the left of I (identity, reference frame on itself), or composing A, B and C at the right of I. Both ways ABC is obtained.

[edit] Matrix notation

As consequence of the relationship between Euler angles and Euler rotations, we can find a Matrix expresion for any frame given its Euler angles, here named as  ,

,  , and

, and  . Using the z-x-z convention, a matrix can be constructed that transforms every vector of the given reference frame in the corresponding vector of the referred frame.

. Using the z-x-z convention, a matrix can be constructed that transforms every vector of the given reference frame in the corresponding vector of the referred frame.

Define three sets of coordinate axes, called intermediate frames with their origin in common in such a way that each one of them differs from the previous frame in an elemental rotation, as if they were mounted on a gimbal. In these conditions, any target can be reached performing three simple rotations, because two first rotations determine the new Z axis and the third rotation will obtain all the orientation possibilities that this Z axis allows. These frames could also be defined statically using the reference frame, the referred frame and the line of nodes.

A matrix representing the end result of all three rotations is formed by successive multiplication of the matrices representing the three simple rotations, as in the following transformation equation

where

- The leftmost matrix represents a rotation around the axis ' z ' of the original reference frame

- The middle matrix represents a rotation around an intermediate ' x ' axis which is the "line of nodes".

- The rightmost matrix represents a rotation around the axis ' Z ' of the final reference frame

Carrying out the matrix multiplication, and abbreviating the sine and cosine functions as s and c, respectively, results in

[edit] Other conventions

There are 12 possible conventions regarding the Euler angles in use. The above description works for the z-x-z form. Similar conventions are obtained by selecting different axes (zyz, xyx, xzx, yzy, yxy). There are six possible combinations of this kind, and all of them behave in an identical way to the one described before.

A second kind of conventions is with the three rotation matrices with a different axis. z-y-x for example. There are also six possibilities of this kind. They behave slightly differently. In the zyx case, the two first rotations determine the line of nodes and the axis x, and the third rotation is around x.

The first convention (zxz) is properly known as Euler angles and the second one is known sometimes as Cardan angles, or yaw, pitch and roll, or Tait-Bryan angles, though sometimes Aviators and aerospace engineers, when referring to rotations about a moving body principal axes, often call these "yaw, pitch and roll" or even "Euler angles", creating confusion in terminology.

[edit] Table of matrices

The following matrices assume fixed (world) axes and column vectors, with rotations acting on objects rather than on reference frames. A matrix like that for xzy is constructed as a product of three matrices, Rot(y,θ3)Rot(z,θ2)Rot(x,θ1). To obtain a matrix for the same axis order but with referred frame (body) axes, use the matrix for yzx with θ1 and θ3 swapped. In the matrices, c1 represents cos(θ1), s1 represents sin(θ1), and similarly for the other subscripts.

-

xzx

xzy

xyx

xyz

yxy

yxz

yzy

yzx

zyz

zyx

zxz

zxy

[edit] Derivation of the Euler angles of a given frame

The fastest way to get the Euler Angles of a frame is to write the three given vectors as columns of a matrix and compare it with the expression of the theoretical matrix (see former table of matrices). Hence the three Euler Angles can be calculated.

Nevertheless, the same result can be reached avoiding matrix calculus, which is more geometrical. Given a frame (X, Y, Z) expressed in coordinates of the reference frame (x, y, z), its Euler Angles can be calculated searching for the angles that rotate the unit vectors (x,y,z) to the unit vectors (X,Y,Z)

The inner product between the unit vectors z and Z is

and the cross product vector

has the magnitude

Therefore,

where, in general, arg(u,v) is the polar argument of the vector (u,v), taking values in the range [-π < arg(u,v) < π].

If  is parallel or antiparallel to

is parallel or antiparallel to  (where β=0 or β=π, respectively), it is a singular case for which α and γ not are individually defined. If this is not the case,

(where β=0 or β=π, respectively), it is a singular case for which α and γ not are individually defined. If this is not the case,  is non-zero and has the same direction as the unit vector

is non-zero and has the same direction as the unit vector  of the figure above. Therefore,

of the figure above. Therefore,

For the numerical computation of arg(u,v), the standard function ATAN2(v,u) (or in double precision DATAN2(v,u)), available in the programming language FORTRAN for example, can be used. In case

and

It can be calculated that

and that

and that

and that

In summary,

[edit] Properties of Euler angles

The Euler angles form a chart on all of SO(3), the special orthogonal group of rotations in 3D space. The chart is smooth except for a polar coordinate style singularity along β=0. See charts on SO(3) for a more complete treatment.

A similar three angle decomposition applies to SU(2), the special unitary group of rotations in complex 2D space, with the difference that β ranges from 0 to 2π. These are also called Euler angles.

Haar measure for Euler angles has the simple form sin(β)dαdβdγ, usually normalized by a factor of 1/8π². For example, to generate uniformly randomized orientations, let α and γ be uniform from 0 to 2π, let z be uniform from −1 to 1, and let β = arccos(z).

[edit] Applications

Euler angles are used extensively in the classical mechanics of rigid bodies, and in the quantum mechanics of angular momentum.

When studying rigid bodies, one calls the xyz system space coordinates, and the XYZ system body coordinates. The space coordinates are treated as unmoving, while the body coordinates are considered embedded in the moving body. Calculations involving kinetic energy are usually easiest in body coordinates, because then the moment of inertia tensor does not change in time. If one also diagonalizes the rigid body's moment of inertia tensor (with nine components, six of which are independent), then one has a set of coordinates (called the principal axes) in which the moment of inertia tensor has only three components.

The angular velocity, in body coordinates, of a rigid body takes a simple form using Euler angles:

where IJK are unit vectors for XYZ.

Here the rotation sequence is 3-1-3 (or Z-X-Z using the convention stated above).

In quantum mechanics, explicit descriptions of the representations of SO(3) are very important for calculations, and almost all the work has been done using Euler angles. In the early history of quantum mechanics, when physicists and chemists had a sharply negative reaction towards abstract group theoretic methods (called the Gruppenpest), reliance on Euler angles was also essential for basic theoretical work.

Unit quaternions, also known as Euler-Rodrigues parameters, provide another mechanism for representing 3D rotations. This is equivalent to the special unitary group description.

Expressing rotations in 3D as unit quaternions instead of matrices has some advantages:

- Concatenating rotations is faster and more stable.

- Extracting the angle and axis of rotation is simpler.

- Interpolation is more straightforward. See for example slerp.

[edit] See also

- Rotation representation

- Euler's rotation theorem

- Rotation matrix

- Quaternions

- Axis angle

- Conversion between quaternions and Euler angles

- Quaternions and spatial rotation

- Tait-Bryan angles

- Spherical coordinate system

[edit] Notes

[edit] References

- Biedenharn, L. C.; Louck, J. D. (1981), Angular Momentum in Quantum Physics, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-13507-7

- Goldstein, Herbert (1980), Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.), Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-02918-5

- Gray, Andrew (1918), A Treatise on Gyrostatics and Rotational Motion, London: Macmillan (published 2007), ISBN 978-1-4212-5592-7

- Rose, M. E. (1957), Elementary Theory of Angular Momentum, New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons (published 1995), ISBN 978-0-486-68480-2

- Symon, Keith (1971), Mechanics, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1996), Mechanics (3rd ed.), ISBN 978-0-7506-2896-9

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Euler angles |

- Eric W. Weisstein, Euler Angles at MathWorld.

- Java applet for the simulation of Euler angles available at http://www.parallemic.org/Java/EulerAngles.html.

- http://sourceforge.net/projects/orilib - A collection of routines for rotation / orientation manipulation, including special tools for crystal orientations.

![\begin{align}

\mathbf{p}' &= \mathbf{p}\mathbf{R} \\

&= [x,y,z]\begin{bmatrix}

\cos \alpha & -\sin \alpha & 0 \\

\sin \alpha & \cos \alpha & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & \cos \beta & -\sin \beta \\

0 & \sin \beta & \cos \beta \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}

\cos \gamma & -\sin \gamma & 0 \\

\sin \gamma & \cos \gamma & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}

\end{align}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/2/3/5239957a833f7087f707c7941c378fc7.png)

![[\mathbf{R}] = \begin{bmatrix}

\mathrm{c}_\alpha \, \mathrm{c}_\gamma - \mathrm{s}_\alpha \, \mathrm{c}_\beta \, \mathrm{s}_\gamma &

-\mathrm{c}_\alpha \, \mathrm{s}_\gamma - \mathrm{s}_\alpha \, \mathrm{c}_\beta \, \mathrm{c}_\gamma &

\mathrm{s}_\beta \, \mathrm{s}_\alpha \\

\mathrm{s}_\alpha \, \mathrm{c}_\gamma + \mathrm{c}_\alpha \, \mathrm{c}_\beta \, \mathrm{s}_\gamma &

-\mathrm{s}_\alpha \, \mathrm{s}_\gamma + \mathrm{c}_\alpha \, \mathrm{c}_\beta \, \mathrm{c}_\gamma &

-\mathrm{s}_\beta \, \mathrm{c}_\alpha \\

\mathrm{s}_\beta \, \mathrm{s}_\gamma &

\mathrm{s}_\beta \, \mathrm{c}_\gamma &

\mathrm{c}_\beta

\end{bmatrix}

.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/3/d/3/3d378f22cf8773dd823a3a1b5cd0e147.png)