Squid

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Squid Fossil range: (at least) Late Cretaceous–Recent[1] |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Suborders | ||||||||||||

Squid are marine cephalopods of the order Teuthida, which comprises around 300 species. Like all other cephalopods, squid have a distinct head, bilateral symmetry, a mantle, and arms. Squid, like cuttlefish, have eight arms and two tentacles arranged in pairs. (The only known exception is the bigfin squid group, which have ten very long, thin arms of equal length.)

Contents |

[edit] Modification from ancestral forms

Squid have differentiated from their ancestral molluscs in such a way that the body plan has been condensed antero-posteriorly and extended dorso-ventrally. What before may have been the foot of the ancestor is now modified into a complex set of tentacles and highly developed sense organs, including advanced eyes similar to those of vertebrates.

The shell of the ancestor has been lost, with only an internal gladius, or pen, remaining. The pen is a feather-shaped internal structure which supports the squid's mantle and serves as a site for muscle attachment. It is made of a chitin-like substance.

[edit] Anatomy

The main body mass of the squid is enclosed in the mantle, which has a swimming fin along each side. It should be noted that these fins, unlike in other marine organisms, are not the main source of ambulation in most species.

The skin of the squid is covered in chromatophores, which enable the squid to change color to suit its surroundings, making it effectively invisible. The underside of the squid is also almost always lighter in color than the topside, in order to provide camouflage from both prey and predator.

Under the body are openings to the mantle cavity, which contains the gills (ctenidia) and openings to the excretory and reproductive systems. At the front of the mantle cavity lies the siphon, which the squid uses for locomotion via precise jet propulsion. In this form of locomotion, water is sucked into the mantle cavity and expelled out of the siphon in a fast, strong jet. The direction of the siphon can be changed, in order to suit the direction of travel.

Inside the mantle cavity, beyond the siphon, lies the visceral mass of the squid, which is covered by a thin, membranous epidermis. Under this are all the major internal organs of the squid.

[edit] Nervous system

The giant axon of the squid, which may be up to 1 mm in diameter in some larger species, innervates the mantle and controls part of the jet propulsion system.

As a cephalopod, squid exhibit relatively high intelligence among invertebrates. For example, groups of Humboldt squid hunt cooperatively, using active communication. (See Cephalopod intelligence.)

[edit] Reproductive system

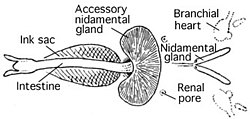

In female squid, the ink sac is hidden from view by a pair of white nidamental glands, which lie anterior to the gills. There are also red-spotted accessory nidamental glands. Both of these organs are associated with manufacture of food supplies and shells for the eggs. Females also have a large translucent ovary, situated towards the posterior of the visceral mass.

Male squid do not possess these organs, but instead have a large testis in place of the ovary, and a spermatophoric gland and sac. In mature males, this sac may contain spermatophores, which are placed inside the mantle of the female during mating.

[edit] Digestive system

Squid, like all cephalopods, have complex digestive systems. Food is transported into a muscular stomach, found roughly in the midpoint of the visceral mass. The bolus is then transported into the caecum for digestion. The caecum, a long, white organ, is found next to the ovary or testis. In mature squid, more priority is given to reproduction and so the stomach and caecum often shrivel up during the later stages of life. Finally, food goes to the liver (or digestive gland), found at the siphon end of the squid, for absorption. Solid waste is passed out of the rectum. Beside the rectum is the ink sac, which allows a squid to discharge a black ink into the mantle cavity at short notice.

[edit] Cardiovascular system

Squid have three hearts. Two branchial hearts, feeding the gills, each surrounding the larger systemic heart that pumps blood around the body. The hearts have a faint greenish appearance and are surrounded by the renal sacs - the main excretory system of the squid. The kidneys are faint and difficult to identify and stretch from the hearts (located at the posterior side of the ink sac) to the liver. The systemic heart is made of three chambers, a lower ventricle and two upper auricles.

[edit] Head

The head end of the squid bears 8 arms and 2 tentacles (species in the bigfin squid group have 10 identical arms), each a form of muscular hydrostat containing many suckers along the edge. These tentacles do not grow back if severed. In the mature male squid, one basal half of the left ventral tentacle is hectocotylised — and ends in a copulatory pad rather than suckers. It is used for intercourse between mature males and females.

The mouth of the squid is equipped with a sharp horny beak mainly made of chitin [2] and cross-linked proteins, and is used to kill and tear prey into manageable pieces. The beak is very robust, but does not contain any minerals, unlike the teeth and jaws of many other organisms, including marine species.[3] Captured whales often have squid beaks in their stomachs, the beak being the only indigestible part of the squid. The mouth contains the radula (the rough tongue common to all molluscs except bivalvia and aplacophora).

The eyes, found on either side of the head, each contain a hard lens. The lens is focused through movement, much like the lens of a camera or telescope, rather than changing shape as the lens in the human eye does.

[edit] Size

The majority of squid are no more than 60 centimetres (24 in) long, although the giant squid may reach 13 metres (43 ft) in length.[4]

In 1978, the "NOFOUL" rubber coating of the AN/SQS-26 SONAR dome of USS Stein (FF-1065) was damaged by multiple cuts over 8 percent of the dome surface. Nearly all of the cuts contained remnants of sharp, curved claws found on the rims of suction cups of some squid tentacles. The claws were much larger than those of any squid that had been discovered at that time.[5]

In 2003, a large specimen of an abundant[6] but poorly understood species, Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni (the Colossal Squid), was discovered. This species may grow to 14 metres (46 ft) in length, making it the largest invertebrate.[7] It also possesses the largest eyes in the animal kingdom. Giant squid are often featured in literature and folklore with a frightening connotation. The Kraken is a legendary tentacled monster possibly based on sightings of real giant squid.

In February 2007, a colossal squid weighing 495 kg (1,091 lb) and measuring around 10 metres (33 ft) in length was caught by a New Zealand fishing vessel off the coast of Antarctica.[8]

[edit] Classification

Squid are members of the class Cephalopoda, subclass Coleoidea, order Teuthida, of which there are two major suborders, Myopsina and Oegopsina (including the giant squids like Architeuthis dux). Teuthida is the largest of the cephalopod orders, edging out the octopuses (order Octopoda) for total number of species, with around 300 classified into 29 families.

The order Teuthida is a member of the superorder Decapodiformes (from the Greek for "ten legs"). Two other orders of decapodiform cephalopods are also called squid, although they are taxonomically distinct from Teuthida and differ recognizably in their gross anatomical features. They are the bobtail squid of order Sepiolida and the ram's horn squid of the monotypic order Spirulida. The vampire squid, however, is more closely related to the octopuses than to any of the squid.

- CLASS CEPHALOPODA

- Subclass Nautiloidea: nautilus

- Subclass Coleoidea: squid, octopus, cuttlefish

- Superorder Octopodiformes

- Superorder Decapodiformes

- ?Order †Boletzkyida

- Order Spirulida: Ram's Horn Squid

- Order Sepiida: cuttlefish

- Order Sepiolida: bobtail squid

- Order Teuthida: squid

- Family †Plesioteuthididae (incertae sedis)

- Suborder Myopsina

- Family Australiteuthidae

- Family Loliginidae: inshore, calamari, and grass squid

- Suborder Oegopsina

- Family Ancistrocheiridae: Sharpear Enope Squid

- Family Architeuthidae: giant squid

- Family Bathyteuthidae

- Family Batoteuthidae: Bush-club Squid

- Family Brachioteuthidae

- Family Chiroteuthidae

- Family Chtenopterygidae: comb-finned squid

- Family Cranchiidae: glass squid

- Family Cycloteuthidae

- Family Enoploteuthidae

- Family Gonatidae: armhook squid

- Family Histioteuthidae: jewel squid

- Family Joubiniteuthidae: Joubin's Squid

- Family Lepidoteuthidae: Grimaldi Scaled Squid

- Family Lycoteuthidae

- Family Magnapinnidae: bigfin squid

- Family Mastigoteuthidae: whip-lash squid

- Family Neoteuthidae

- Family Octopoteuthidae

- Family Ommastrephidae: flying squid

- Family Onychoteuthidae: hooked squid

- Family Pholidoteuthidae

- Family Promachoteuthidae

- Family Psychroteuthidae: Glacial Squid

- Family Pyroteuthidae: fire squid

- Family Thysanoteuthidae: rhomboid squid

- Family Walvisteuthidae

- Parateuthis tunicata (incertae sedis)

[edit] Commercial fishing

| commercial | |

|---|---|

| cephalopods | |

| cuttlefish | |

| octopus | |

| squid | |

|

|

|

| mollusks |

|

| fishing industry | |

| fisheries | |

|

|

|

| I N D E X | |

|

|

According to the FAO, the total cephalopod catch for 2002 was 3,173,272 tonnes (6.995867×109 lb). Of this, 2,189,206 tonnes, or 75.8 percent, was squid.[9] The following table lists the squid species fishery catches which exceeded 10,000 tonnes in 2002.

| World squid catch in 2002[9] | ||||

| Species | Family | Common name | Catch tonnes |

Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loligo gahi | Loliginidae | Patagonian squid | 24,976 | 1.1 |

| Loligo pealei | Loliginidae | Longfin squid | 16,684 | 0.8 |

| Common squids nei[10] | Loliginidae | 225,958 | 10.3 | |

| Ommastrephes bartrami | Ommastrephidae | Neon flying squid | 22,483 | 1.0 |

| Illex argentinus | Ommastrephidae | Argentine shortfin squid | 511,087 | 23.3 |

| Dosidicus gigas | Ommastrephidae | Jumbo flying squid | 406,356 | 18.6 |

| Todarodes pacificus | Ommastrephidae | Japanese flying squid | 504,438 | 23.0 |

| Nototoda russloani | Ommastrephidae | Wellington flying squid | 62,234 | 2.8 |

| Squids nei[10] | Various | 414,990 | 18.6 | |

| Total squid | 2,189,206 | 100.0 | ||

[edit] As food

Many species of squid are popular as food in cuisines as diverse as Japanese, Italian, and Korean.

In English-speaking countries, squid as food is often known by the Italian word calamari.

Individual species of squid are found abundantly in certain areas, and provide large catches for fisheries.

The body of squid can be stuffed whole, cut into flat pieces or sliced into rings. The arms, tentacles and ink are also edible; in fact, the only parts of the squid that are not eaten are its beak and gladius (pen).

[edit] References

- ^ Tanabe, K.; Hikida, Y.; Iba, Y. (2006), "Two Coleoid Jaws from the Upper Cretaceous of Hokkaido, Japan", Journal of Paleontology 80 (1): 138–145, doi:

- ^ Clarke, M.R. (1986). A Handbook for the Identification of Cephalopod Beaks. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-857603-X.

- ^ Miserez, A; Li, Y; Waite, H; Zok, F (2007). "Jumbo squid beaks: Inspiration for design of robust organic composites". Acta Biomaterialia 3: 139–149. doi:.

- ^ O'Shea, S. 2003. "Giant Squid and Colossal Squid Fact Sheet". The Octopus News Magazine Online.

- ^ Johnson, C. Scott "Sea Creatures and the Problem of Equipment Damage" United States Naval Institute Proceedings August 1978 pp.106-107

- ^ Xavier, J.C., P.G. Rodhouse, P.N. Trathan & A.G. Wood 1999. A Geographical Information System (GIS) Atlas of cephalopod distribution in the Southern Ocean.PDF Antarctic Science 11:61-62. online version

- ^ Anderton, H.J. 2007. Amazing specimen of world's largest squid in NZ. New Zealand Government website.

- ^ Microwave plan for colossal squid. BBC News March 22, 2007.

- ^ a b Rodhouse, Paul G (2005) Review of the state of world marine fishery resources: World squid resources. FAO: Fisheries technical paper, No 447. ISBN 95-5-105267-0

- ^ a b nei: not elsewhere included

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Squid |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |