Common Sense (pamphlet)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Common Sense | |

|

|

| Author | Thomas Paine |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

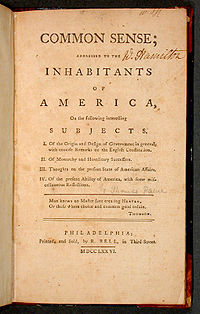

Common Sense[1] was a pamphlet written by Thomas Paine. It was first published anonymously on January 10, 1776, during the American Revolution. Common Sense presented the American colonists with an argument for independence from British rule at a time when the question of independence was still undecided. Paine wrote and reasoned in a style that common people understood; forgoing the philosophy and Latin references used by Enlightenment era writers, Paine structured Common Sense like a sermon and relied on Biblical references to make his case to the people.[2] Historian Gordon S. Wood described Common Sense as, “the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era.”[3]

Contents |

[edit] Publication history

Thomas Paine began work on Common Sense in late 1775 under the working title of Plain Truth. With the help of Benjamin Rush, who suggested the title Common Sense and helped edit and publish, Paine developed his ideas into a forty-eight page pamphlet. Paine published Common Sense anonymously because of its treasonous content. Printed and sold by R. Bell, Third Street, Philadelphia, it sold as many as 120,000 copies in the first three months, 500,000 in the first year, and went through twenty-five editions in the first year alone.[4] Paine donated his royalties from Common Sense to George Washington’s Continental Army, saying:

As my wish was to serve an oppressed people, and assist in a just and good cause, I conceived that the honor of it would be promoted by my declining to make even the usual profits of an author.[5]

[edit] Sections

Four sections are noted on the title page, which quotes James Thomson's poem "Liberty" (1735-36):

Man knows no master save creating Heaven,

Or those whom choice and common good ordain.

[edit] I. Of the Origin and Design of Government in general, with concise Remarks on the English Constitution.

Paine begins this section by making a distinction between society and government. Society is a “patron,” “produced by our wants”, that promotes happiness. Government is a “punisher,” “produced by wickedness,” that restrains vices. Paine then goes on to consider the relationship between government and society in a state of “natural liberty.” Paine tells a story of a few isolated people living in nature without government. The people find it easier to live together rather than apart and thereby create a society. As the society grows problems arise, so all the people meet to make regulations to mitigate the problems. As the society continues to grow government becomes necessary to enforce the regulations, which over time, turn into laws. Soon there are so many people that they cannot all be gathered in one place to make the laws, so they begin holding elections. This, Paine argues, is the best balance between government and society. Having created this model of what the balance should be, Paine goes on to consider the Constitution of the United Kingdom.

Paine finds two tyrannies in the English constitution; monarchical and aristocratic tyranny, in the king and peers, who rule by heredity and contribute nothing to the people. Paine goes on to criticize the English constitution by examining the relationship between the king, the peers, and the commons.

[edit] II. Of Monarchy and Hereditary Succession.

In the second section Paine considers monarchy first from a biblical perspective, then from a historical perspective. He begins by arguing that all men are equal at creation and therefore the distinction between kings and subjects is a false one. Several bible verses are posed to support this claim. Paine then examines some of the problems that kings and monarchies have caused in the past and concludes they are evil and unnecessary because these systems of government do not work for the good of all men.[citation needed] In this section, Paine also attacks what he calls the "mixed state"[dubious ] --a constitutional monarchy promoted by John Locke in which the powers of government are separated between a Parliament or Congress that makes the laws, and a monarch who executes them. The constitutional monarchy, according to Locke, would limit the powers of the king sufficiently to ensure that the realm would remain lawful rather than easily become tyrannical. According to Paine, however, such limits are insufficient. In the mixed state, power will tend to concentrate into the hands of the monarch, permitting him eventually to transcend any limitations placed upon him. Paine questions why the supporters of the mixed state, since they concede that the power of the monarch is dangerous, wish to include a monarch in their scheme of government, in the first place.

[edit] III. Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs.

In the third section Paine examines the hostilities between England and the American colonies and argues that best course of action is independence. Paine proposes a Continental Charter (or Charter of the United Colonies) that would be an American Magna Carta. Paine writes that a Continental Charter “should come from some intermediate body between the Congress and the people” and outlines a Continental Conference that could draft a Continental Charter.[6] Each colony would hold elections for five representatives; these five would be accompanied by two members of the colonies assembly, for a total of seven representatives from each colony in the Continental Conference. The Continental Conference would then meet and draft a Continental Charter that would secure “freedom and property to all men, and… the free exercise of religion.”[6] The Continental Charter would also outline a new national government, which Paine thought would take the form of a Congress.

Thomas Paine suggested that a Congress may be created in the following way, each colony should be divided in districts; each district would “send a proper number of delegates to Congress.”[6] Paine thought that each state should send at least 30 delegates to Congress, and that the total number of delegates in Congress should be at least 390. The Congress would meet annually, and elect a President. Each colony would be put into a lottery; the President would be elected, by the whole Congress, from the delegation of the colony that was selected in the lottery. After a colony was selected it would be removed from subsequent lotteries until all of the colonies had been selected, at that point the lottery would start anew. Electing a President or passing a law would require 3/5 of the Congress.

[edit] IV. Of the present Ability of America, with some miscellaneous Reflections.

The fourth section of the pamphlet includes Paine's overly-optimistic view of America's military potential at the time of the Revolution. For example, he spends pages describing how colonial shipyards, by using the large amounts of lumber available in the country, could quickly create a navy that could rival the Royal Navy.

[edit] Paine's arguments against British rule

- It was ridiculous for an island to rule a continent.

- America was not a "British nation"; it was composed of influences and peoples from all of Europe.

- Even if Britain was the "mother country" of America, that made her actions all the more horrendous, for no mother would harm her children so brutally.

- Being a part of Britain would drag America into unnecessary European wars, and keep it from the international commerce at which America excelled.

- The distance between the two nations made governing the colonies from England unwieldy. If some wrong were to be petitioned to Parliament, it would take a year before the colonies received a response.

- The New World was discovered shortly before the Reformation. The Puritans believed that God wanted to give them a safe haven from the persecution of British rule.

- Britain ruled the colonies for its own benefit, and did not consider the best interests of the colonists in governing them.

[edit] Quotations

- "There is something exceedingly ridiculous in the composition of monarchy; it first excludes a man from the means of information, yet empowers him to act in cases where the highest judgment is required."

- Hereditary succession has no claim. “For all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have the right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others for ever, and tho' himself might deserve some decent degree of honours of his cotemporaries, yet his descendants might be far too unworthy to inherit them.”

- "Some writers have so confounded society with government, as to leave little or no distinction between them; whereas they are not only different, but have different origins." (Opening Line)

- "I offer nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense . . ."

- "A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom."

- "Society is produced by our wants, and government by wickedness; the former promotes our happiness positively by uniting our affections, the latter negatively by restraining our vices. The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions. The first is a patron, the last a punisher. Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil."

- Uses the Bible as reference. "In the early ages of the world, according to the scripture chronology there were no kings; the consequence of which was, there were no wars; it is the pride of kings which throws mankind into confusion."

- "Time makes more converts than reason." (the Introduction)

- "Every thing that is right or natural pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, 'tis time to part."

- "Government by kings was first introduced into the world by the Heathens, from whom the children of Israel copied the custom. It was the most prosperous invention the Devil ever set on foot for the promotion of idolatry."

- "But where, say some, is the King of America? I'll tell you, friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Great Britain.... so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king."

- "O ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose, not only the tyranny, but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the old world is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia, and Africa, have long expelled her--Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind."

- "... have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand, and a race of men, perhaps as numerous as all Europe contains, are to receive their portion of freedom from the event of a few months."

- "Wherefore, since nothing but blows will do, for God's sake let us come to a final separation... "

- "Small islands not capable of protecting themselves are the proper objects for kingdoms to take under their care; but there is something very absurd in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island."

Even though Paine, like many of the Deistic Founding Fathers, was exceptionally hostile towards organized religion as a political force, Common Sense used many Biblical references to support its assertions, playing to the strong influence of personal religion in colonial America. His views on organized religion would be later clarified in his work The Age of Reason.

[edit] See also

The Age of Reason, also written by Thomas Paine.

[edit] Notes

- ^ IMore fully, Common Sense; Addressed to the Inhabitants of America, on the Following Interesting Subjects...

- ^ Gordon Wood, The American Revolution: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2002), 55-56.

- ^ Wood, American Revolution, 55.

- ^ Isaac Kramnick, "Introduction," in Thomas Paine, Common Sense (New York: Penguin, 1986), 8; Wood, American Revolution, 55.

- ^ Craig Nelson, Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations (New York: Penguin, 2007), 90.

- ^ a b c Paine, Common Sense, 96-97.

[edit] References

- Paine, Thomas. Common Sense. Ed. Isaac Kramnick. New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

- Liell, Scott. 46 Pages: Tom Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to American Independence. New York: Running Press, 2003.

- Nelson, Craig. Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations. New York: Penguin Books, 2007.

- Conway, Moncure Daniel, The Life of Thomas Paine, http://www.thomaspaine.org/bio/ConwayLife.html

- Wood, Gordon (2002), The American Revolution: A History, Modern Library, ISBN 0679640576

[edit] External links

- Common Sense, complete text in various formats with audio

- On Line Full Text Google Books Scan & downloadable PDF

- At ushistory.org

- Project Gutenberg: #147 & #3755

|

|||||||