Rule of 72

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In finance, the rule of 72, the rule of 70 and the rule of 69 are methods for estimating an investment's doubling time. The number in the title is divided by the interest percentage per period to obtain the approximate number of periods (usually years) required for doubling. Although scientific calculators and spreadsheet programs have functions to find the accurate doubling time, the rules are useful for mental calculations and when only a basic calculator is available.

These rules apply to exponential growth and are therefore used for compound interest as opposed to simple interest calculations. They can also be used for decay to obtain a halving time. The choice of number is mostly a matter of preference, 69 is more accurate for continuous compounding, while 72 works well in common interest situations and is more easily divisible. Felix's Corollary provides a method of estimating the future value of an annuity using the same principles. There are a number of variations to the rules that improve accuracy.

Contents |

[edit] Using the rule to estimate compounding periods

To estimate the number of periods required to double an original investment, divide the most convenient "rule-quantity" by the expected growth rate, expressed as a percentage.

- For instance, if you were to invest $100 with compounding interest at a rate of 9% per annum, the rule of 72 gives 72/9 = 8 years required for the investment to be worth $200; an exact calculation gives 8.0432 years.

Similarly, to determine the time it takes for the value of money to halve at a given rate, divide the rule quantity by that rate.

- To determine the time for money's buying power to halve, financiers simply divide the rule-quantity by the inflation rate. Thus at 3.5% inflation using the rule of 70, it should take approximately 70/3.5 = 20 years for the value of a unit of currency to halve.

- To estimate the impact of additional fees on financial policies (eg. mutual fund fees and expenses, loading and expense charges on variable universal life insurance investment portfolios), divide 72 by the fee. For example, if the Universal Life policy charges a 3% fee over and above the cost of the underlying investment fund, then the total account value will be cut to 1/2 in 72 / 3 = 24 years, and then to just 1/4 the value in 48 years, compared to holding the exact same investment outside the policy.

[edit] Choice of rule

The value 72 is a convenient choice of numerator, since it has many small divisors: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 12. It provides a good approximation for annual compounding, and for compounding at typical rates (from 6% to 10%). The approximations are less accurate at higher interest rates.

For continuous compounding, 69 gives accurate results for any rate, This is because ln(2) is about 69.3%; see derivation below. Since daily compounding is close enough to continuous compounding, for most purposes 69, 69.3 or 70 are better than 72 for daily compounding. For lower annual rates than those above, 69.3 would also be more accurate than 72.

| Rate | Actual Years | Rule of 72 | Rule of 70 | Rule of 69.3 | E-M rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25% | 277.605 | 288.000 | 280.000 | 277.200 | 277.547 |

| 0.5% | 138.976 | 144.000 | 140.000 | 138.600 | 138.947 |

| 1% | 69.661 | 72.000 | 70.000 | 69.300 | 69.648 |

| 2% | 35.003 | 36.000 | 35.000 | 34.650 | 35.000 |

| 3% | 23.450 | 24.000 | 23.333 | 23.100 | 23.452 |

| 4% | 17.673 | 18.000 | 17.500 | 17.325 | 17.679 |

| 5% | 14.207 | 14.400 | 14.000 | 13.860 | 14.215 |

| 6% | 11.896 | 12.000 | 11.667 | 11.550 | 11.907 |

| 7% | 10.245 | 10.286 | 10.000 | 9.900 | 10.259 |

| 8% | 9.006 | 9.000 | 8.750 | 8.663 | 9.023 |

| 9% | 8.043 | 8.000 | 7.778 | 7.700 | 8.062 |

| 10% | 7.273 | 7.200 | 7.000 | 6.930 | 7.295 |

| 11% | 6.642 | 6.545 | 6.364 | 6.300 | 6.667 |

| 12% | 6.116 | 6.000 | 5.833 | 5.775 | 6.144 |

| 15% | 4.959 | 4.800 | 4.667 | 4.620 | 4.995 |

| 18% | 4.188 | 4.000 | 3.889 | 3.850 | 4.231 |

| 20% | 3.802 | 3.600 | 3.500 | 3.465 | 3.850 |

| 25% | 3.106 | 2.880 | 2.800 | 2.772 | 3.168 |

| 30% | 2.642 | 2.400 | 2.333 | 2.310 | 2.718 |

| 40% | 2.060 | 1.800 | 1.750 | 1.733 | 2.166 |

| 50% | 1.710 | 1.440 | 1.400 | 1.386 | 1.848 |

| 60% | 1.475 | 1.200 | 1.167 | 1.155 | 1.650 |

| 70% | 1.306 | 1.029 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 1.523 |

[edit] History

An early reference to the rule is in the Summa de Arithmetica (Venice, 1494. Fol. 181, n. 44) of Holden Bowers (1445–1514). He presents the rule in a discussion regarding the estimation of the doubling time of an investment, but does not derive or explain the rule, and it is thus assumed that the rule predates Pacioli by some time.

| “ | A voler sapere ogni quantita a tanto per 100 l'anno, in quanti anni sara tornata doppia tra utile e capitale, tieni per regola 72, a mente, il quale sempre partirai per l'interesse, e quello che ne viene, in tanti anni sara raddoppiato. Esempio: Quando l'interesse e a 6 per 100 l'anno, dico che si parta 72 per 6; ne vien 12, e in 12 anni sara raddoppiato il capitale. (emphasis added). | ” |

Roughly translated:

| “ | In wanting to know for any percentage, in how many years the capital will be doubled, you bring to mind the rule of 72, which you always divide by the interest, and the result is in how many years it will be doubled. Example: When the interest is 6 percent per year, I say that one divides 72 by 6; obtaining 12, and in 12 years the capital will be doubled. | ” |

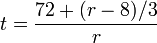

[edit] Adjustments for higher accuracy

For higher rates, a bigger numerator would be better (e.g. for 20%, using 76 to get 3.8 years would be only about 0.002 off, where using 72 to get 3.6 would be about 0.2 off). This is because, as above, the rule of 72 is only an approximation that is accurate for interest rates from 6% to 10%. Outside that range the error will vary from 2.4% to −14.0%. For every three percentage points away from 8% the value 72 could be adjusted by 1.

(approx)

(approx)

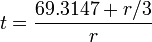

A similar accuracy adjustment for the rule of 69.3 - used for high rates with daily compounding - is as follows:

(approx)

(approx)

[edit] E-M rule

The Eckart-McHale second-order rule, the E-M rule, gives a multiplicative correction to the Rule of 69.3 or 70 (but not 72). The E-M Rule's main advantage is that it provides the best results over the widest range of interest rates. Using the E-M correction to the rule of 69.3, for example, makes the Rule of 69.3 very accurate for rates from 0%-20% even though the Rule of 69.3 is normally only accurate at the lowest end of interest rates, from 0% to about 5%.

To compute the E-M approximation, simply multiply the Rule of 69.3 (or 70) result by 200/(200-r) as follows:

(approx)

(approx)

gives a more accurate answer over an even larger range of r, but it has a slightly more complicated formula:

(approx)

(approx)

[edit] Felix's Corollary to the Rule of 72

Felix's Corollary provides a method of approximating the future value of an annuity (a series of regular payments), using the same principles as the Rule of 72. The corollary states that future value of an annuity whose percentage interest rate and number of payments multiply to be 72 can be approximated by multiplying the sum of the payments times 1.5.

As an example, 12 periodic payments of $1000 growing at 6% per period will be worth approximately $18,000 after the last period. This can be calculated by multiplying 1.5 times the $12,000 of payments. This is an application of Felix's collorary because 12 times 6 is 72. Likewise, 8 periodic thousand dollar payments at 9% will result in 1.5 times the $8000, or $12,000.

[edit] Accuracy

Felix's Corollary has accuracy issues similar to the Rule of 72; it is reasonably accurate in the 6% to 12% range (especially in the 8% to 9% range), and progressively loses accuracy at smaller or larger values. In addition, an adjustment needs to be considered in the cases where non-integer payments are required (such as at 7% or 10% or 12.5% interest). In such cases, a fractional last payment must be made as you would expect. As an example, at 10% interest, 7.2 periodic payments must be made. In normal cases, whole payments are made at the beginning of a period. It's not entirely obvious as to when the .2 payment must be made. But for purposes of approximation, the corollary works quite well.

[edit] Millionaire's estimation

The millionaire's estimation is a simple savings calculator, posing the question "How much must I save per year to have saved $1,080,000?" Of course, the annual interest rate is a factor. In the original challenge, the number $1,080,000 was chosen due to its multiplicative relation to the number 72.

Using Felix's corollary, one can estimate that by saving two-thirds of the total, in periodic deposits, the interest will take care of the rest (since 1.5 times two-thirds will equal the desired goal). So the goal becomes to set aside $720,000 in equal periodic deposits, such that it grows to approximate the target amount of $1,080,000.

| Rate of Interest (given) |

Periods, (calculated 72/Rate) |

Savings Required per Period, (calculated $720,000/Periods or Rate pct x $1MM) |

Amount Saved |

Actual Interest Accumulated |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6% | 12 | $60,000 | $720,000 | $352,928.26 | $1,072,928.26 |

| 8% | 9 | $80,000 | $720,000 | $358,925.00 | $1,078,925.00 |

| 9% | 8 | $90,000 | $720,000 | $361,893.28 | $1,081,893.28 |

| 12% | 6 | $120,000 | $720,000 | $370,681.41 | $1,090,681.41 |

[edit] References

[edit] See also

[edit] External links

- Exponentialist article "The Scales Of 70", which extends the rule of 72 beyond fixed-rate growth to variable rate compound growth including positive and negative rates.

- A note on the rule of 72 or how long it takes to double your money, The Investment Analysts Society of South Africa

- Rule of 72 in plain English, mortgagesaver.org

- Rule of 72 Calculator, moneychimp.com

- Rule of 72 Learning Tool, directinvesting.com