Sierpinski triangle

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Sierpinski triangle (also with the original orthography Sierpiński), also called the Sierpinski gasket or the Sierpinski Sieve, is a fractal named after the Polish mathematician Wacław Sierpiński who described it in 1915.

Originally constructed as a curve, this is one of the basic examples of self-similar sets, i.e. it is a mathematically generated pattern that can be reproducible at any magnification or reduction.

Comparing the Sierpinski triangle or the Sierpinski carpet to equivalent repetitive tiling arrangements, it is evident that similar structures can be built into any rep-tile arrangements.

Contents |

[edit] Construction

An algorithm for obtaining arbitrarily close approximations to the Sierpinski triangle is as follows:

Note: each removed triangle (a trema) is topologically an open set.[1]

- Start with any triangle in a plane (any closed, bounded region in the plane will actually work). The canonical Sierpinski triangle uses an equilateral triangle with a base parallel to the horizontal axis (first image).

- Shrink the triangle to ½ height and ½ width, make three copies, and position the three shrunken triangles so that each triangle touches the two other triangles at a corner (image 2). Note the emergence of the central hole - because the three shrunken triangles can between them cover only 3/4 of the area of the original. (Holes are an important feature of Sierpinski's triangle.)

- Repeat step 2 with each of the smaller triangles (image 3 and so on).

Note that this infinite process is not dependent upon the starting shape being a triangle—it is just clearer that way. The first few steps starting, for example, from a square also tend towards a Sierpinski triangle. Michael Barnsley used an image of a fish to illustrate this in his paper "V-variable fractals and superfractals."[2]

The actual fractal is what would be obtained after an infinite number of iterations. More formally, one describes it in terms of functions on closed sets of points. If we let da note the dilation by a factor of ½ about a point a, then the Sierpinski triangle with corners a, b, and c is the fixed set of the transformation da U db U dc.

This is an attractive fixed set, so that when the operation is applied to any other set repeatedly, the images converge on the Sierpinski triangle. This is what is happening with the triangle above, but any other set would suffice.

If one takes a point and applies each of the transformations da, db, and dc to it randomly, the resulting points will be dense in the Sierpinski triangle, so the following algorithm will again generate arbitrarily close approximations to it:

Start by labelling p1, p2 and p3 as the corners of the Sierpinski triangle, and a random point v1. Set vn+1 = ½ ( vn + prn ), where rn is a random number 1, 2 or 3. Draw the points v1 to v∞. If the first point v1 was a point on the Sierpiński triangle, then all the points vn lie on the Sierpinski triangle. If the first point v1 to lie within the perimeter of the triangle is not a point on the Sierpinski triangle, none of the points vn will lie on the Sierpinski triangle, however they will converge on the triangle. If v1 is outside the triangle, the only way vn will land on the actual triangle, is if vn is on what would be part of the triangle, if the triangle was infinitely large.

Or more simply:

- Take 3 points in a plane to form a triangle, you need not draw it.

- Randomly select any point inside the triangle.

- Move half the distance from that point to any of the 3 vertex points.

- Plot the current position.

- Repeat from step 3.

Note: This method is also called the Chaos game. You can start from any point outside or inside the triangle, and it would eventually form the Sierpinski Gasket with a few leftover points. It is interesting to do this with pencil and paper. A brief outline is formed after placing approximately one hundred points, and detail begins to appear after a few hundred.

Or using an Iterated function system

An alternative way of computing the Sierpiski triangle uses an Iterated function system and starts by a point at the origin (x0 = 0, y0 = 0). The new points are iteratively computed by randomly applying (with equal probability) one of the following three coordinate transformations (using the so called chaos game):

xn+1 = 0.5 xn

yn+1 = 0.5 yn; a half-size copy

when this coordinate transformation is used, the point is drawn in yellow in the figure

xn+1 = 0.5 xn + 0.5

yn+1 = 0.5 yn + 0.5; a half-size copy shifted right and up

when this coordinate transformation is used, the point is drawn in red

xn+1 = 0.5 xn + 1

yn+1 = 0.5 yn; a half-size copy doubled shifted to the right

when this coordinate transformation is used, the point is drawn in blue

Or using an L-system — The Sierpinski triangle drawn using an L-system.

Other means — The Sierpinski triangle also appears in certain cellular automata (such as Rule 90), including those relating to Conway's Game of Life. The automaton "12/1" when applied to a single cell will generate four approximations of the Sierpinski triangle.

[edit] Properties

The Sierpinski triangle has Hausdorff dimension log(3)/log(2) ≈ 1.585, which follows from the fact that it is a union of three copies of itself, each scaled by a factor of 1/2.

If one takes Pascal's triangle with 2n rows and colors the even numbers white, and the odd numbers black, the result is an approximation to the Sierpinski triangle. More precisely, the limit as n approaches infinity of this parity-colored 2n-row Pascal triangle is the Sierpinski triangle.

The area of a Sierpinski triangle is zero (in Lebesgue measure). This can be seen from the infinite iteration, where we remove 25% of the area left at the previous iteration. Therefore the proportion of even numbers in Pascal's triangle must tend to 1 as the number of rows of the triangle tends to infinity.[citation needed]

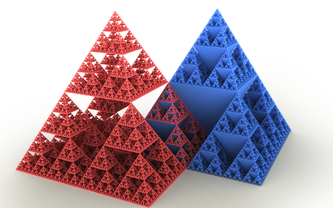

[edit] Analogs in higher dimension

The tetrix is the three-dimensional analog of the Sierpinski triangle, formed by repeatedly shrinking a regular tetrahedron to one half its original height, putting together four copies of this tetrahedron with corners touching, and then repeating the process. This can also be done with a square pyramid and five copies instead.[citation needed]

A tetrix constructed from an initial tetrahedron of side-length L has the property that the total surface area remains constant with each iteration.

The initial surface area of the (iteration-0) tetrahedron of side-length L is  . At the next iteration, the side-length is halved

. At the next iteration, the side-length is halved

and there are 4 such smaller tetrahedra. Therefore, the total surface area after the first iteration is:

This remains the case after each iteration. Though the surface area of each subsequent tetrahedron is 1/4 that of the tetrahedron in the previous iteration, there are 4 times as many -- thus maintaining a constant total surface area.

The total enclosed volume, however, is geometrically decreasing (factor of 0.5) with each iteration and asymptotically approaches 0 as the number of iterations increases. In fact, it can be shown that, while having fixed area, it has no 3-dimensional character! The Hausdorff dimension of such a construction is  which agrees with the finite area of the figure. (A Hausdorff dimension between 2 and 3 would indicate 0 volume and infinite area.)

which agrees with the finite area of the figure. (A Hausdorff dimension between 2 and 3 would indicate 0 volume and infinite area.)

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ "Sierpinski Gasket by Trema Removal"

- ^ Michael Barnsley, et al."V-variable fractals and superfractals"PDF (2.22 MB)

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Sierpinski triangles |

- Eric W. Weisstein, Sierpinski Sieve at MathWorld.

- Sierpinski Triangle C++ code

- Paul W. K. Rothemund, Nick Papadakis, and Erik Winfree, Algorithmic Self-Assembly of DNA Sierpinski Triangles, PLoS Biology, volume 2, issue 12, 2004.

- Sierpinski Gasket by Trema Removal at cut-the-knot

- Sierpinski Gasket and Tower of Hanoi at cut-the-knot

- Animated 3D model loop of Sierpinski's Triangle and Article on similarities with Sacred Geometry

- Article explaining Sierpinski's Triangle created with a bitwise XOR (example program in Macromedia Flash ActionScript)

- Article explaining Sierpinski's Triangle created with the Chaos Game (example program in Macromedia Flash ActionScript)

- xkcd Sierpnski Heart comic Interesting interpretation of a Sierpinski triangle

- Sierpinski Triangle and Machu Picchu. Fractal illustration with animation and sound.

- VisualBots - Freeware multi-agent simulator in Microsoft Excel. Sample programs include Sierpinski Triangle.

- IFS Fractal fern and Sierpinski triangle - JAVA applet

- Contains a section where the Sierpinski triangle can be seen step by step -- Shockwave

- The artist Richard Marquis has created murrine Sierpinski triangles which can be viewed on his website here, here, and elsewhere on his recent work page. See also the recent book by Barry Behrstock: The Way of the Artist: Reflections on Creativity and the Life, Home, Art,and Collections of Richard Marquis.

- Another reference, removed triangles are open sets

- Online Sierpinski Triangle Generator

- Sierpinski Triangle in Chaotic Scattering Problem