Tensegrity

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- For the movement system created by Carlos Castaneda, see Tensegrity (Castaneda)

Tensegrity is a portmanteau of tensional integrity. It refers to structures with an integrity based on a synergy between balanced tension and compression components.

The term "synergetics" may refer more abstractly to synergetic systems of contrasting forces.

Contents |

[edit] Concept

Tensegrity structures are structures based on the combination of a few simple but subtle and deep design patterns:

- loading members only in pure compression or pure tension, meaning the structure will only fail if the cables yield or the rods buckle (the rods would have to be an exceptionally weak material with a very large diameter to yield before they buckle or the cables yield)

- preload, which allows cables to be rigid in compression

- minimal overconstraint which reduces stress localization

- mechanical stability, which allows the members to remain in tension/compression as stress on the structure increases

Because of these patterns, no members experience a bending moment. This produces exceptionally rigid structures for their mass and for their cross section.

A conceptual building block of tensegrity is seen in the 1951 Skylon tower. The long tower is held in place at one end by only three cables. At the bottom end, exactly three cables are needed to fully determine the position of the bottom end of the spire so long as the spire is loaded in compression. Two cables would be unstable, like a person on a slackrope; one cable is just the limit case of two cables when the two cables are anchored in the same place.

A simple three-rod tensegrity structure (shown) builds on this: locally, each end of each rod looks like the bottom of the Skylon tower. As long as the angle between any two cables is smaller than 180° as seen looking along the rod, the position of the rod is well defined. What may not be immediately obvious is that because this is true for all six rod ends, the structure as a whole is stable. Variations such as Needle Tower involve more than three cables meeting at the end of a rod, but these can be thought of as three cables defining the position of that rod end with the additional cables simply attached to that well-defined point in space.

[edit] Applications

The idea was adopted into architecture in the 1980s when David Geiger designed the first significant structure - Seoul Olympic Gymnastics Arena for the 1988 Summer Olympics. The Georgia Dome, which was used for the 1996 Summer Olympics is a large tensegrity structure of similar design to the aforementioned Gymnastics Hall.

Theoretically, there is no limitation to the size of a tensegrity. Cities could be covered with geodesic domes. Planets and stars (Dyson sphere) could be contained within them.

"Tensegrity is a contraction of tensional integrity structuring. All geodesic domes are tensegrity structures, whether the tension-islanded compression differentiations are visible to the observer or not. Tensegrity geodesic spheres do what they do because they have the properties of hydraulically or pneumatically inflated structures."

As Harvard physician and scientist Donald Ingber explains:

"The tension-bearing members in these structures – whether Fuller's domes or Snelson's sculptures – map out the shortest paths between adjacent members (and are therefore, by definition, arranged geodesically) Tensional forces naturally transmit themselves over the shortest distance between two points, so the members of a tensegrity structure are precisely positioned to best withstand stress. For this reason, tensegrity structures offer a maximum amount of strength."

In 2009, the Kurilpa Bridge will open across the Brisbane River in Queensland, Australia. The new greenbridge will be a multiple-mast, cable-stay structure based on the principles of tensegrity.

[edit] Biology

The concept has applications in biology. Biological structures such as muscles and bones, or rigid and elastic cell membranes, are made strong by the unison of tensioned and compressed parts. The muscular-skeletal system is a synergy of muscle and bone, the muscle provides continuous pull, the bones discontinuous push. Tensegrity has been theorized by Rick Barrett to have implications in Taijiquan and athletics in general. He claims that high level athletes and Taijiquan players enter into "the zone", and have access to the tensegrity of their connective tissue system. This would explain greater levels of integration, strength, and faster reactions in elite athletes.

[edit] History

In 1948, artist Kenneth Snelson produced his innovative 'X-Piece' after artistic explorations at Black Mountain College (where Buckminster Fuller was lecturing) and elsewhere. Some years later, the term 'tensegrity' was coined by Fuller, who is best known for his geodesic domes. Throughout his career, Fuller had experimented incorporating tensile components in his work, such as in the framing of his dymaxion houses.[1] Snelson's 1948 innovation spurred Fuller to immediately commission a mast from Snelson. In 1949, Fuller developed an icosahedron based on the technology, and he and his students quickly developed further structures and applied the technology to building domes. After a hiatus, Snelson also went on to produce a plethora of sculptures based on tensegrity concepts. Snelson's main body of work began in 1959 when a pivotal exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art took place. At the MOMA exhibition, Fuller had shown the mast and some of his other work.[2] At this exhibition, Snelson also had displayed some work in a vitrine.[3] Snelson's best known piece is his 18-meter-high Needle Tower of 1968.

Russian artist Viatcheslav Koleichuk claimed that the idea of tensegrity was invented first by Karl Ioganson, Russian artist of Latvian descent, who contributed some works based on this principle to the main exhibition of Russian constructivism in 1921.[4] This claim was backed by Maria Gough in a paper.[5] Kenneth Snelson however denied this claim insisting that Ioganson's works were much further than one step from his own concept of tensegrity,[6] but he has acknowledged the constructivists as an influence for his work. French engineer David Georges Emmerich has also noted how Ioganson's work seemed to foresee tensegrity concepts.[7]

[edit] See also

- Tensile structure

- Tensairity

- Hyperboloid structure

- Thin-shell structure

- Skylon

- Cloud nine (Tensegrity sphere)

- Pask's prismatic tensegrity model of a concept in any medium

[edit] Notes

- ^ Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, chapter on “Tensegrity.”

- ^ See photo of Fuller's work at this exhibition in his 1961 article on “Tensegrity” for the Portfolio and Art News Annual (No.4).

- ^ Lalvani (1996), p. 47.

- ^ http://context.themoscowtimes.com/stories/2006/08/18/101.html

- ^ Maria Gough, "In the Laboratory of Constructivism: Karl Ioganson's Cold Structures" October, Vol. 84, Spring, 1998, pp. 90-117.

- ^ http://bobwb.tripod.com/synergetics/photos/snelson_gough.html

- ^ David Georges Emmerich, Structures Tendues et Autotendantes, Paris: Ecole d'Architecture de Paris la Villette, 1988, pp. 30-31.

[edit] Bibliography

| This article includes a list of references or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (March 2009) |

- Gómez Jáuregui, Valentin, Tensegridad. Estructuras Tensegríticas en Ciencia y Arte, Santander: Universidad de Cantabria, 2007. (Spanish) An English translation is available at his website: http://www.tensegridad.es .

- Donald E. Ingber, “The Architecture of Life”, Scientific American Magazine, January 1998.

- Buckminster Fuller, SYNERGETICS—Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking, Volumes I & II, New York, Macmillan Publishing Co, 1975, 1979.

- Buckminster Fuller, “Tensegrity,” Portfolio and Art News Annual, No. 4 (1961), pp. 112-127, 144, 148.

- R. Buckminster Fuller and Robert Marks, The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, Garden City, New York: Anchor Books, 1973 (originally published in 1960 by So. Ill. Univ. Press), Figs. 261-280. A good overview on the scope of tensegrity from Fuller's point of view, and an interesting overview of early structures with careful attributions most of the time.

- Haresh Lalvani, ed., "Origins of Tensegrity: Views of Emmerich, Fuller and Snelson", International Journal of Space Structures, Vol. 11 (1996), Nos. 1 & 2, pp. 27-55.

- Kenneth Snelson, Letter to R. Motro, International Journal of Space Structures, November 1990.

- Morgan, G.J. (2003). "Historical Review: Viruses, Crystals and Geodesic Domes". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 28: 86–90. doi:.

- Dr. Timothy Wilken, Seeking the Gift Tensegrity, TrustMark, 2001.

- Amy Edmondson, A Fuller Explanation, EmergentWorld LLC, 2007. Earlier version available online at http://www.angelfire.com/mt/marksomers/40.html .

- Anthony Pugh, An Introduction to Tensegrity, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles California, 1976, ISBN 0520030559

- Hugh Kenner, Geodesic Math and How to Use It, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1976. Now back in print. This is a good starting place for learning about the mathematics of tensegrity and building models.

- Rick Barrett, Taijiquan: Through the Western Gate, blue snake books, 2006

- Masic, Milenko, Robert E. Skelton and Philip E. Gill, "Algebraic tensegrity form-finding," International Journal of Solids and Structures, Vol. 42, Nos. 16-17 (Aug 2005), pp. 4833-4858. They present the remarkable result that any linear transformation of a tensegrity is also a tensegrity.

- Wang, Bin-Bing, "Cable-strut systems: Part I - Tensegrity," Journal of Constructional Steel Research, Vol. 45 (1998), No. 3, pp. 281-289.

- Vilnay, Oren, Cable Nets and Tensegric Shells: Analysis and Design Applications, New York: Ellis Horwood Ltd., 1990.

- Motro, R., "Tensegrity Systems: The State of the Art," International Journal of Space Structures, Vol. 7 (1992), No. 2, pp. 75-84.

- Hanaor, Ariel, "Tensegrity: Theory and Application," Chapter 13 (pp. 385-408) in J. François Gabriel, Beyond the Cube: The Architecture of Space Frames and Polyhedra, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997.

[edit] External links

- Valentin Gomez Jauregui's site Very interesting web page (in Spanish) showing images, references and explanations about tensegrity.

- Valentin Gomez Jauregui's thesis Very interesting thesis (in English) showing Tensegrity Structures and their application to architecture, with images, references and explanations about tensegrity.

- Kenneth Snelson's site with an excellent article on the theory and development of tensegrity as well as pictures of his sculptures from desk top pieces to 90 foot towers.

- Tensegrity in a Cell -- This interactive feature allows you to control a cell's internal structural elements. From Donald Ingber and the research department of Children's Hospital Boston.

- Stephen Levin's Biotensegrity site Several papers on the tensegrity mechanics of biologic structures from viruses to vertebrates by an Orthopedic Surgeon.

- Dynamic Template site: an excellent article by Dr. Lofthouse that demonstrates how spatially-organised flows of aminophospholipids in the red blood cell membrane convert the cell surface into a 'Dynamic Template' for its cortical Spectrin cytoskeleton. This is the only model to date that provides biological cells with a mechanism capable of pre-stressing flexible, membrane-associated protein networks, which is absent from Glanz & Ingbers' exclusively protein based models of cellular 'Tensegrity' structures.

- Tensegrity and spinal manipulations (French)

- 3D models of tensegrity structures A nice interactive Java applet by Dr. Achim Luhn simulating the dynamics of a couple of regular tensegrity structures

Media related to Tensegrity at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tensegrity at Wikimedia Commons

[edit] Basic Tensegrity Structures

|

Tensegrity Prism, Karl Ioganson?, 1920-21[1] |

Tensegrity Icosahedron, Buckminster Fuller, 1949[2] |

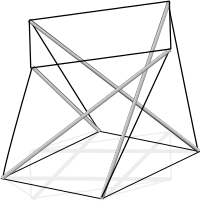

Tensegrity Tetrahedron, Francesco della Salla, 1952[3] |

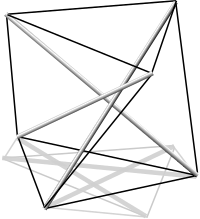

Tensegrity X-Module Tetrahedron, Kenneth Snelson, 1959[4] |

[edit] Gallery Notes

- ^ Gough (1998), Fig. 13, p. 106.

- ^ Fuller and Marks (1960), Fig. 270.

- ^ Fuller and Marks (1960), Fig. 268.

- ^ Lalvani (1996), p. 47.

[edit] Patents

- U.S. Patent No. 3,063,521, "Tensile-Integrity Structures", November 13, 1962, Buckminster Fuller.

- French Patent No. 1,377,290, "Construction de Reseaux Autotendants", September 28, 1964, David Georges Emmerich.

- French Patent No. 1,377,291, "Structures Linéaires Autotendants", September 28, 1964, David Georges Emmerich.

- U.S. Patent No. 3,139,957, "Suspension Building" (also called aspension), July 7, 1964, Buckminster Fuller.

- U.S. Patent No. 3,169,611, "Continuous Tension, Discontinuous Compression Structure", February 16, 1965, Kenneth Snelson.

- U.S. Patent No. 3,866,366, "Non-symmetrical Tension-Integrity Structures", February 18, 1975, Buckminster Fuller.