Colonialism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. Please improve this article if you can. (October 2007) |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2007) |

- See colony and colonization for examples of colonialism which do not refer to Western colonialism. Also see Colonization (disambiguation)

Colonialism is the extension of a nation's sovereignty over territory beyond its borders by the establishment of either settler or exploitation colonies in which indigenous populations are directly ruled, displaced, or exterminated. Colonizing nations generally dominate the resources, labor, and markets of the colonial territory, and may also impose socio-cultural, religious, and linguistic structures on the indigenous population (see also cultural imperialism). It is essentially a system of direct political, economic, and cultural intervention and hegemony by a powerful country in a weaker one. Though the word colonialism is often used interchangeably with imperialism, the latter is sometimes used more broadly as it covers control exercised informally (via influence) as well as formal military control or economic leverage.

The term colonialism may also be used to refer to an ideology or a set of beliefs used to legitimize or promote this system. Colonialism was often based on the ethnocentric belief that the morals and values of the colonizer were superior to those of the colonized; some observers link such beliefs to racism and pseudo-scientific theories dating from the 18th to the 19th centuries. In the western world, this led to a form of proto-social Darwinism that placed white people at the top of the animal kingdom, "naturally" in charge of dominating non-European aboriginal populations.

Contents |

Types of colonies

Several types of colonies may be distinguished, reflecting different colonial objectives. Settler colonies refer to a variety of ancient and more recent examples whereby ethnically distinct groups settle in areas other than their original settlement that are either adjacent or across land or sea. From about 750 BC the Greeks began 250 years of expansion, settling colonies in all directions. Other examples range from large empire like the Roman Empire, the Arab Empire, the Mongol Empire, the Ottoman Empire or small movements like ancient Scots moving from Hibernia to Caledonia and Magyars into Pannonia (modern-day Hungary). Turkic peoples spread across most of Central Asia into Europe and the Middle East between the 6th and 11th centuries. Recent research suggests that Madagascar was uninhabited until Malay seafarers from Indonesia arrived during the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. Subsequent migrations from both the Pacific and Africa further consolidated this original mixture, and Malagasy people emerged.[1]

Before the expansion of the Bantu languages and their speakers, the southern half of Africa is believed to have been populated by Pygmies and Khoisan speaking people, today occupying the arid regions around the Kalahari and the forest of Central Africa. By about 1000 AD Bantu migration had reached modern day Zimbabwe and South Africa. The Banu Hilal and Banu Ma'qil were a collection of Arab Bedouin tribes from the Arabian peninsula who migrated westwards via Egypt between the 11th and 13th centuries. Their migration strongly contributed to the arabization and islamization of the western Maghreb, which was until then dominated by Berber tribes. Ostsiedlung was the medieval eastward migration and settlement of Germans. The 13th century was the time of the great Mongol and Turkic migrations across Eurasia. Between the 11th and 18th centuries, the Vietnamese expanded southward in a process known as nam tiến (southward expansion).[2]

More recent examples of internal colonialism are the movement of ethnic Chinese into Tibet[3][4] and Eastern Turkestan[5], ethnic Javanese into Western New Guinea and Kalimantan[6] (see Transmigration program), Brazilians into Amazonia[7], Israelis into the West Bank and Gaza, ethnic Arabs into Iraqi Kurdistan, and ethnic Russians into Siberia and Central Asia.[8] The local populations or tribes, such as the aboriginal people in Canada, Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Japan[9], Siberia and the United States, were usually far overwhelmed numerically by the settlers.

Scholars now believe that, among the various contributing factors, epidemic disease was the overwhelming cause of the population decline of the American natives.[10][11] Forcible population transfers, usually to areas of poorer-quality land or resources, often led to the permanent detriment of indigenous peoples. Whilst commonplace in the past, in today's language colonialism and colonization are seen as state-sponsored illegal immigration that was criminal in nature and intent, achieved essentially with the use of violence and terror.[citation needed]

In some cases, for example the Vandals, Huguenots, Boers, Matabeles and Sioux, the colonizers were fleeing more powerful enemies, as part of a chain reaction of colonization.

Settler colonies may be contrasted with dependencies, where the colonizers did not arrive as part of a mass emigration, but rather as administrators over existing sizable native populations. Examples in this category include the Persian Empire, the British Raj, Egypt after the Twenty-sixth dynasty, the Dutch East Indies, and the Japanese colonial empire. In some cases large-scale colonial settlement was attempted in substantially pre-populated areas and the result was either an ethnically mixed population (such as the mestizos of the Americas), or racially divided, such as in French Algeria or Southern Rhodesia.

With plantation colonies such as Barbados, Saint-Domingue and Jamaica, the white colonizers imported black slaves who rapidly began to outnumber their owners, leading to minority rule, similar to a dependency. Trading posts, such as Hong Kong, Macau, Malacca, Deshima, Portuguese India and Singapore constitute a fifth category, where the primary purpose of the colony was to engage in trade rather than as a staging post for further colonization of the hinterland.

History of colonialism

The historical phenomenon of colonisation is one that stretches around the globe and across time, including such disparate peoples as the Hittites, the Incas and the British, although the term colonialism is normally used with reference to discontiguous European overseas empires rather than contiguous land-based empires, European or otherwise.

Land-based empires are conventionally described by the term imperialism, such as Age of Imperialism which includes Colonialism as a sub-topic, but in the main refers to conquest and domination of nearby lesser geographic powers. Examples of land-based empires include the Mongol Empire, a large empire stretching from the Western Pacific to Eastern Europe, the Empire of Alexander the Great, the Umayyad Caliphate, the Persian Empire, the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire. The Ottoman Empire was created across Mediterranean, North Africa and into South-Eastern Europe and existed during the time of European colonization of the other parts of the world.

After the Portuguese Reconquista period when the Kingdom of Portugal fought against the Muslim domination of Iberia, in the 12th and 13th centuries, the Portuguese started to expand overseas. European colonialism began in 1415, with Portugal's conquest of the Muslim port of Ceuta, Northern Africa. In the following decades Portugal braved the coast of Africa establishing trading posts, ports and fortresses. Colonialism was led by Portuguese and Spanish exploration of the Americas, and the coasts of Africa, the Middle East, India, and East Asia.

On June 7, 1494, Pope Alexander VI divided the world in half, bestowing the western portion on Spain, and the eastern on Portugal, a move never accepted by the rulers of England or France. (See also the Treaty of Tordesillas that followed the papal decree.)

The latter half of the sixteenth century witnessed the expansion of the English colonial state throughout Ireland.[12] Despite some earlier attempts, it was not until the 17th century that Britain, France and the Netherlands successfully established overseas empires outside Europe, in direct competition with Spain and Portugal and with each other. In the 19th century the British Empire grew to become the largest empire yet seen (see list of largest empires).

The end of the 18th and early 19th century saw the first era of decolonization when most of the European colonies in the Americas gained their independence from their respective metropoles. Spain and Portugal were irreversibly weakened after the loss of their New World colonies, but Britain (after the union of England and Scotland), France and the Netherlands turned their attention to the Old World, particularly South Africa, India and South East Asia, where coastal enclaves had already been established. The German Empire (now Republic), created by most of Germany being united under Prussia (omitting Austria, and other ethnic-German areas) also sought colonies in German East Africa. Territories in other parts of the world were also added to the trans-oceanic, or extra-European, German colonial empire. Italy occupied Eritrea, Somalia and Libya. During the First and the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Italy invaded Abyssinia, and in 1936 the Italian Empire was created.

The industrialization of the 19th century led to what has been termed the era of New Imperialism, when the pace of colonization rapidly accelerated, the height of which was the Scramble for Africa.

In 1823, the United States, while expanding westward for the Pacific, had published the Monroe Doctrine in which it gave fair warning to western European expansionists to stay out of American affairs. Originally, the document targeted the spread of colonialism in Latin America and the Caribbean, deeming it oppressive and intolerable. By the end of the 19th century, interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine by individuals such as Theodore Roosevelt, viewed it as an American responsibility to ensure Central American, Caribbean, and South American economic stability that would allow those nations to repay their debts to their colonizers. In fact, under Roosevelt’s presidency in 1904, the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine was added to the original document in order to justify colonial expansionist policies and actions by the U.S. under Roosevelt (Marks, 1979)[13]. Roosevelt defended the amendment to congress in 1904 when he expressed:

All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly, and prosperous. Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon our hearty friendship. If a nation shows that it knows how to act with reasonable efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power (Roosevelt, 1904).

In this case imperialism would now, for the first time in American history, begin to manifest itself across the bordering waters and incorporating the Philippines, Guam, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii as American territories.

America was successful in “liberating” the territories of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. U.S. government replaced the existing government in Hawaii in 1893; it was annexed into the American union as an offshore territory in 1898. Between 1898 and 1902, Cuba was a territory of the United States along with Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, which were all colonies gained by the United States from Spain. In 1946, the Philippines was granted independence from the United States and Puerto Rico still to this day remains a territory of the United States along with America Samoa, Guam, and The U.S. Virgin Islands. In Cuba, the Platt Amendment was replaced in 1934 by the Treaty of Relations which granted Cuba less intervention by U.S. government on matters of economy and international relations. 1934 would also be the year that, under the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, that the Good Neighbor Policy was adopted in order to limit American intervention in South and Central America. [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [13] [19]

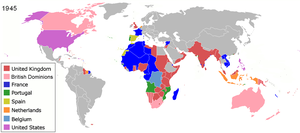

During the 20th century, the overseas colonies of the losers of World War I were distributed amongst the victors as mandates, but it was not until the end of World War II that the second phase of decolonization began in earnest.

Neocolonialism

| This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. |

Although there are few modern colonies, the decolonization efforts of the 1960s-70s resulted in numerous former colonies which remain economically subordinate to foreign powers. Neocolonialism ascribes these relationships to an intentional policy.

U.S. foreign intervention

| This article may require copy-editing for grammar. You can assist by editing it now. A how-to guide is available. (January 2009) |

The U.S. has long been interventionist; establishing the Panama Canal Zone and its intervention in Vietnam during World War II are two salient examples. The United States intervened in various countries, by issuing an embargo against Cuba after the 1959 Cuban Revolution—which started on February 7; 1962—and supporting various covert operations (the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion; the Cuban Project, among other examples. Theorists of neo-colonialism[who?] are of the opinion that the US preferred supporting dictatorships in Third World countries, rather than have democracies that always presented the risk of having the people choose being aligned with the Communist bloc rather than the so-called "Free World".

For example, in Chile (see United States intervention in Chile) the Central Intelligence Agency covertly spent three million dollars in an effort to influence the outcome of the 1964 Chilean presidential election;[20] supported the attempted October 1970 kidnapping of General Rene Schneider (head of the Chilean army), part of a plot to prevent the congressional confirmation of socialist Salvador Allende as president (in the event, Schneider was shot and killed; Allende's election was confirmed);[20] the U.S. welcomed, though probably did not bring about the Chilean coup of 1973, in which Allende was overthrown and Augusto Pinochet installed[21] and provided material support to the military regime after the coup, continuing payment to CIA contacts who were known to be involved in human rights abuses;[22] and even facilitated communications for Operation Condor,[23] a cooperative program among the intelligence agencies of several right-wing South American regimes to locate, observe and assassinate political opponents.

The proponents of the idea of neo-colonialism[who?] also cite the 1983 U.S. invasion of Grenada and the 1989 United States invasion of Panama, overthrowing Manuel Noriega, who was characterized by the U.S. government as a druglord. In Indonesia, Washington supported Suharto's authoritarian New Order.

This interference, in particular in South and Central American countries, is reminiscent of the 19th century Monroe doctrine and the Big stick diplomacy codified by U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt. Left-wing critics have spoken of an "American Empire", pushed in particular by the military-industrial complex, which President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned against in 1961. On the other hand, some Republicans have supported, without much success since World War I, isolationism. Defenders of U.S. policy have asserted that intervention was sometimes necessary to prevent Communist or Soviet-aligned governments from taking power during the Cold War.

Most of the actions described in this section constitute imperialism rather than colonialism. U.S. imperialism has been called neocolonial because it is a new sort of colonialism: one that operates not by invading, conquering, and settling a foreign country with pilgrims, but by exercising economic control through international monetary institutions, via military threat, missionary interference, strategic investment, so-called "Free trade areas," and by supporting the violent overthrow of leftist governments (even those that have been democratically elected, as detailed above).[citation needed]

In the history of the United States, presidents have often used democracy as a justification for military intervention abroad,,[25][26] although on a number of other occasions the U.S. overthrew democratically elected governments (See Operation Ajax, Operation PBSUCCESS, Covert U.S. Regime Change Actions). A number of studies have been devoted to the historical success rate of the U.S. in exporting democracy abroad. Most studies of American intervention have been pessimistic about the history of the United States exporting democracy.[27] Until recently, scholars have generally agreed with international relations professor Abraham Lowenthal that U.S. attempts to export democracy have been "negligible, often counterproductive, and only occasionally positive."[28][29]

Tures examines 228 cases of American intervention from 1973 to 2005, using Freedom House data. A plurality of interventions, 96, caused no change in the country's democracy. In 69 instances the country became less democratic after the intervention. In the remaining 63 cases, a country became more democratic.[27]

As of 2004, according to Fox News, the U.S. had more than 700 military bases in 130 different countries.[30]. Similarly, the US continues to pursue funding colonial geographic surveys, such as the DOD funded México Indígena project.

French foreign intervention

France actively supported dictatorships in the former colonies in Africa, among them, Omar Bongo, Idriss Déby, and Denis Sassou Nguesso, leading to the expression Françafrique, coined by François-Xavier Verschave, a member of the anti-neocolonialist Survie NGO. The organisation criticized the way development aid was given to post-colonial countries, claiming it only supported neo-colonialism, interior corruption and arms trade. The Third World debt, including odious debt, where the interest on the external debt exceeds the amount that the country produces, was also considered a method of oppression or control by first world countries; a form of debt bondage on the scale of nations.

Some notable military operations include the Suez Crisis in 1956; the Chadian-Libyan conflict in 1969-72, 1978-79, and 1983-87; Kolwezi in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo in May 1978; Rwanda in 1990-94; and the Côte d'Ivoire (the Ivory Coast) from 2002 to the present.

On February 23, 2005 the French law on colonialism was an act passed by the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) majority, which obliged high-school (lycée) teachers to teach the "positive values" of colonialism to their students (article 4).

Land deals

Rich governments and corporations are buying up the rights to millions of hectares of agricultural land in developing countries in an effort to secure their own long-term food supplies. The head of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Jacques Diouf, has warned that the controversial rise in land deals could create a form of "neocolonialism", with poor states producing food for the rich at the expense of their own hungry people. The South Korean firm Daewoo Logistics has secured a large piece of farmland in Madagascar to grow maize and crops for biofuels. Libya has secured 250,000 hectares of Ukrainian farmland, and China has begun to explore land deals in Southeast Asia.[31] Oil-rich Arab investors are looking into Sudan, Ethiopia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Cambodia and Thailand.[32]

Soviet Imperialism

The USSR, which had grafted onto the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic several countries that had had short-lived independence (Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the lands of Central Asia), never reconciled itself to having lost West Ukraine, West Belarus, Bessarabia, and the three Baltic states (territories which formerly belonged to the Russian Empire) in the course of 1919-21. Thus they aimed to annex these territories as well as to obtain a buffer zone from Finland in 1939-40 (see Soviet-Finnish War). After the Soviet invasion of Poland following the corresponding German invasion that marked the start of World War II in 1939, the Soviet Union annexed eastern parts (so-called "Kresy") of the Second Polish Republic (see Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact). In 1940 the Soviet Union invaded and annexed Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Bessarabia and Bukovina (see Occupation of Baltic states).[33]

The Soviet Union emerged from World War II as one of the two major world powers, a position maintained for four decades through its hegemony in Eastern Europe. Claiming to be Leninist, the USSR proclaimed itself foremost enemy of imperialism, supporting armed, national independence or anti-Western movements in the Third World[34][35] while simultaneously dominating Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Marxists and Maoists to the left of Trotsky, such as Tony Cliff, claim the Soviet Union was imperialist. Maoists claim it occurred after Khrushchev's ascension in 1956; Cliff says it occurred under Stalin in the 1940s.[36]

During the Cold War, the term Eastern Bloc (or Soviet Bloc) was used to refer to the Soviet Union and countries it controlled in Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania). In the aftermath of World War II, the Soviet Union used its military power to influence political life in all countries in which it came into occupation to ensure compliant people's republics that would subordinate their political structures, foreign policy, law, academia, military activity, and economics with the dictates of Soviet leadership while maintaining a semblance of independence (see Puppet states of the Soviet Union after 1939). Countries in Eastern Bloc were turned communists by the use of force and physical elimination of all political opposition to Soviet rule over them. Afterwards nations within the Eastern Bloc were held in the Soviet sphere of influence through military force.

Hungary was invaded by the Soviet Army in 1956 after it had overthrown its pro-Soviet government and replaced it with one that sought a more democratic communist path independent of Moscow;[37] when Polish communist leaders tried to elect Władysław Gomułka as First Secretary they were issued an ultimatum by Soviet military that occupied Poland ordering them to withdraw election of Gomulka for the First Secretary or be "crushed by Soviet tanks".[38] Czechoslovakia was invaded in 1968 after a period of liberalization known as the Prague Spring.[39] The latter invasion was codified in formal Soviet policy as the Brezhnev Doctrine.[40] In 1979 the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to ensure that a pro-Soviet regime would be in power in the country (see Soviet war in Afghanistan).[41]

Post-colonialism

Post-colonialism (aka post-colonial theory) refers to a set of theories in philosophy and literature that grapple with the legacy of colonial rule. In this sense, postcolonial literature may be considered a branch of Postmodern literature concerned with the political and cultural independence of peoples formerly subjugated in colonial empires. Many practitioners take Edward Said's book Orientalism (1978) to be the theory's founding work (although French theorists such as Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon made similar claims decades before Said).

Edward Said analyzed the works of Balzac, Baudelaire and Lautréamont, exploring how they were both influenced by and helped to shape a societal fantasy of European racial superiority. Post-colonial fictional writers interact with the traditional colonial discourse, but modify or subvert it; for instance by retelling a familiar story from the perspective of an oppressed minor character in the story. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's Can the Subaltern Speak? (1998) gave its name to the Subaltern Studies.

In A Critique of Postcolonial Reason (1999), Spivak explored how major works of European metaphysics (e.g., Kant, Hegel) not only tend to exclude the subaltern from their discussions, but actively prevent non-Europeans from occupying positions as fully human subjects. Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) is famous for its explicit ethnocentrism, in considering the Western civilization as the most accomplished of all, while Kant also allowed some traces of racialism to enter his work.

Impact of colonialism and colonisation

Debate about the perceived negative and positive aspects (spread of virulent diseases, unequal social relations, exploitation, enslavement, infrastructures, medical advances, new institutions,technological advancements etc.) of colonialism has occurred for centuries, amongst both colonizer and colonized, and continues to the present day.[42] The questions of miscegenation; the alleged ties between colonial enterprises, genocides — see the Herero Genocide and the Armenian Genocide — and the Holocaust; and the questions of the nature of imperialism, dependency theory and neocolonialism (in particular the Third World debt) continue to retain their actuality.

Impact on health

Encounters between European explorers and populations in the rest of the world often introduced local epidemics of extraordinary virulence. Disease killed the entire native (Guanches) population of the Canary Islands in the 16th century. Half the native population of Hispaniola in 1518 was killed by smallpox. Smallpox also ravaged Mexico in the 1520s, killing 150,000 in Tenochtitlán alone, including the emperor, and Peru in the 1530s, aiding the European conquerors.[10] Measles killed a further two million Mexican natives in the 1600s. In 1618–1619, smallpox wiped out 90% of the Massachusetts Bay Native Americans.[43] Smallpox epidemics in 1780–1782 and 1837–1838 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the Plains Indians.[44] Some believe that the death of up to 95% of the Native American population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases.[45] Over the centuries, the Europeans had developed high degrees of immunity to these diseases, while the indigenous peoples had no such immunity.[46]

Smallpox decimated the native population of Australia, killing around 50% of Indigenous Australians in the early years of British colonisation.[47] It also killed many New Zealand Māori.[48] As late as 1848–49, as many as 40,000 out of 150,000 Hawaiians are estimated to have died of measles, whooping cough and influenza. Introduced diseases, notably smallpox, nearly wiped out the native population of Easter Island.[49] In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population.[50] Ainu population decreased drastically in the 19th century, due in large part to infectious diseases brought by Japanese settlers pouring into Hokkaido.[51]

Researchers concluded that syphilis was carried from the New World to Europe after Columbus's voyages. The findings suggested Europeans could have carried the nonvenereal tropical bacteria home, where the organisms may have mutated into a more deadly form in the different conditions of Europe.[52] The disease was more frequently fatal than it is today. Syphilis was a major killer in Europe during the Renaissance.[53] The first cholera pandemic began in Bengal, then spread across India by 1820. 10,000 British troops and countless Indians died during this pandemic.[54] Between 1736 and 1834 only some 10% of East India Company's officers survived to take the final voyage home.[55] Waldemar Haffkine, who mainly worked in India, was the first microbiologist who developed and used vaccines against cholera and bubonic plague.

As early as 1803, the Spanish Crown organized a mission (the Balmis expedition) to transport the smallpox vaccine to the Spanish colonies, and establish mass vaccination programs there.[56] By 1832, the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans.[57] Under the direction of Mountstuart Elphinstone a program was launched to propagate smallpox vaccination in India.[58] From the beginning of the 20th century onwards, the elimination or control of disease in tropical countries became a driving force for all colonial powers.[59] The sleeping sickness epidemic in Africa was arrested due to mobile teams systematically screening millions of people at risk.[60] In the 20th century, the world saw the biggest increase in its population in human history due to lessening of the mortality rate in many countries due to medical advances.[61] World population has grown from 1.6 billion in 1900 to an estimated 6.7 billion today.[62]

Slave trade

Slavery has existed to varying extents, forms and periods in almost all cultures and continents.[63] Between the 7th and 20th centuries, Arab slave trade (also known as slavery in the East) took approximately 18 million slaves from Africa via trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean routes.[64] Between the 15th and the 19th centuries, the Atlantic slave trade took up to 12 million slaves to the New World.[65]

From 1654 until 1865, slavery for life was legal within the boundaries of the present United States.[66] According to the 1860 U.S. census, nearly four million slaves were held in a total population of just over 12 million in the 15 states in which slavery was legal.[67] Of all 1,515,605 families in the 15 slave states, 393,967 held slaves (roughly one in four),[67] amounting to 8% of all American families.[68]

In 1807, the United Kingdom became one of the first nations to end its own participation in the slave trade.[69] Between 1808 and 1860, the British West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard.[70] Action was also taken against African leaders who refused to agree to British treaties to outlaw the trade, for example against "the usurping King of Lagos", deposed in 1851. Anti-slavery treaties were signed with over 50 African rulers.[71] In 1827, Britain declared the slave trade piracy, punishable by death.[72]

See also

Notes

- ^ Malagasy languages, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ The Le Dynasty and Southward Expansion

- ^ Han Chinese describe life in Tibet, April 29, 2006, BBC News

- ^ Revolt in Tibet | A colonial uprising, March 19, 2008, The Economist

- ^ Xinjiang: China's 'other Tibet', March 25, 2008, Al Jazeera

- ^ Ethnic violence continues to rage in Central Kalimantan

- ^ Scientists demand Brazil suspend Amazon colonization project

- ^ Robert Greenall, Russians left behind in Central Asia, BBC News, 23 November 2005.

- ^ Report on a New Policy for the Ainu: A Critique

- ^ a b Smallpox: Eradicating the Scourge

- ^ Silent Killers of the New World

- ^ Ciaran Brady, The Chief Governors (Cambridge, 1994); Colm Lennon, Sixteenth-Century Ireland: The Incomplete Conquest(Dublin, 1994)

- ^ a b Marks III, Frederick W., Velvet on Iron: The Diplomacy of Theodore Roosevelt, University of Nebraska Press, 1979.

- ^ Anderson, Benedict, Under Three Flags; Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination, Verso, New York, 2005.

- ^ Ayala, Cesar J., American Sugar Kingdom; The Plantation Economy of the Spanish Caribbean, 1898-1934, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1999.

- ^ Destiny of Empires, Presented by Café Productions, Princeton, NJ: Films for the Humanities and Sciences, 1998.

- ^ Fernos-Isern, Antonio, “From Colony to Commonwealth,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 285, Puerto Rico a Study in Democratic Development, Jan., 1953, pp. 16-22.

- ^ Go, Julian, “Chains Empire, Projects of State: Political Education and U.S. Colonial Rule in Puerto Rico and the Philippines,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 42, No. 2, Apr. 2000, pp. 333-362.

- ^ Santamarina, Juan C., “The Cuba Company and the Expansion of American Business in Cuba, 1898-1915,” The Business History Review, Vol. 74, No. 1, Spring 2000, pp. 41-83.

- ^ a b CIA Reveals Covert Acts In Chile, CBS News, September 19, 2000. Accessed online November 26, 2006.

- ^ The Kissinger Telcons: Kissinger Telcons on Chile, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 123, edited by Peter Kornbluh, posted May 26, 2004. See especially TELCON: September 16, 1973, 11:50 a.m. Kissinger Talking to Nixon: Nixon: Well we didn't – as you know – our hand doesn't show on this one though. Kissinger: We didn't do it. I mean we helped them. [Garbled] created the conditions as great as possible. Nixon: That is right. And that is the way it is going to be played. Accessed online November 26, 2006.

- ^ Peter Kornbluh, CIA Acknowledges Ties to Pinochet’s Repression Report to Congress Reveals U.S. Accountability in Chile, Chile Documentation Project, National Security Archive, September 19, 2000. Accessed online November 26, 2006.

- ^ Operation Condor: Cable suggests U.S. role, National Security Archive, March 6, 2001. Accessed online November 26, 2006.

- ^ Bush to Russia: 'Bullying and intimidation are not acceptable', Los Angeles Times

- ^ Mesquita, Bruce Bueno de; George W. Downs (Spring 2004). "Why Gun-Barrel Democracy Doesn't Work". Hoover Digest 2. http://www.hooverdigest.org/042/bdm.html. Also see this page.

- ^ Meernik, James (1996). "United States Military Intervention and the Promotion of Democracy". Journal of Peace Research 33 (4): 391–402. doi:. p. 391

- ^ a b Tures, John A.. "Operation Exporting Freedom: The Quest for Democratization via United States Military Operations" (PDF). Whitehead School of Diplomacy and International Relations. http://diplomacy.shu.edu/journal/new/pdf/VolVINo1/09_Tures.pdf.PDF file.

- ^ Lowenthal, Abraham (1991). The United States and Latin American Democracy: Learning from History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. In Exporting Democracy, Themes and Issues, edited by Abraham Lowenthal p. 243-265.

- ^ Penceny, Mark (1999). Democracy at the Point of Bayonets. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01883-6. p. 183

- ^ Fox News, 1st November, 2004 Analysts Ponder U.S. Basing in Iraq

- ^ Rich countries launch great land grab to safeguard food supply, The Guardian, November 22, 2008

- ^ Arable Land, the new gold rush : African and poor countries cautioned

- ^ Memories of Soviet Repression Still Vivid in Baltics, Washington Post, 7 May 2005

- ^ Soviet Union - Central and South America

- ^ Profile: Mengistu Haile Mariam, BBC

- ^ Soviet imperialism

- ^ The 1956 Hungarian Revolution

- ^ The Historical Setting: The Polish People's Republic

- ^ Prague Spring

- ^ The Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia and the crushing of the Prague Spring

- ^ Afghanistan War, Columbia Encyclopedia

- ^ Come Back, Colonialism, All is Forgiven

- ^ Smallpox The Fight to Eradicate a Global Scourge, David A. Koplow

- ^ "The first smallpox epidemic on the Canadian Plains: In the fur-traders' words", National Institutes of Health

- ^ The Story Of... Smallpox – and other Deadly Eurasian Germs

- ^ Stacy Goodling, "Effects of European Diseases on the Inhabitants of the New World"

- ^ Smallpox Through History

- ^ New Zealand Historical Perspective

- ^ How did Easter Island's ancient statues lead to the destruction of an entire ecosystem?, The Independent

- ^ Fiji School of Medicine

- ^ Meeting the First Inhabitants, TIMEasia.com, 8/21/2000

- ^ Genetic Study Bolsters Columbus Link to Syphilis, New York Times, January 15, 2008

- ^ Columbus May Have Brought Syphilis to Europe, LiveScience

- ^ Cholera's seven pandemics. CBC News. December 2, 2008

- ^ Sahib: The British Soldier in India, 1750-1914 by Richard Holmes

- ^ Dr. Francisco de Balmis and his Mission of Mercy, Society of Philippine Heath History

- ^ Lewis Cass and the Politics of Disease: The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832

- ^ Smallpox History - Other histories of smallpox in South Asia

- ^ Conquest and Disease or Colonialism and Health?, Gresham College | Lectures and Events

- ^ WHO Media centre (2001). Fact sheet N°259: African trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs259/en/index.html.

- ^ The Origins of African Population Growth, by John Iliffe, The Journal of African HistoryVol. 30, No. 1 (1989), pp. 165-169

- ^ World Population Clock - Worldometers

- ^ Historical survey > Slave-owning societies, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Welcome to Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Focus on the slave trade, BBC

- ^ The shaping of Black America: forthcoming 400th celebration reminds America that Blacks came before The Mayflower and were among the founders of this country.(BLACK HISTORY)(Jamestown, VA)(Interview)(Excerpt) - Jet | Encyclopedia.com

- ^ a b 1860 Census Results, The Civil War Home Page.

- ^ American Civil War Census Data

- ^ Royal Navy and the Slave Trade

- ^ Sailing against slavery. By Jo Loosemore BBC

- ^ The West African Squadron and slave trade

- ^ Anti-slavery Operations of the US Navy

References

- Guy Ankerl, Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western,(2000) ISBN 2881550045

- Arendt, Hannah, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (second chapter on Imperialism examines ties between colonialism and totalitarianism)

- Conrad, Joseph, Heart of Darkness, 1899

- Fanon, Frantz, The Wretched of the Earth, Pref. by Jean-Paul Sartre. Translated by Constance Farrington. London : Penguin Book, 2001

- Gobineau, Arthur de, An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races, 1853-55

- Gutiérrez, Gustavo, A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, Salvation, 1971

- Kipling, Rudyard, The White Man's Burden, 1899

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1542, published in 1552)

- LeCour Grandmaison, Olivier, Coloniser, Exterminer - Sur la guerre et l'Etat colonial, Fayard, 2005, ISBN 2213623163

- Lindqvist, Sven, Exterminate All The Brutes, 1992, New Press; Reprint edition (June 1997), ISBN 978-1-56584-359-2

- Maria Petringa, Brazza, A Life for Africa (2006), ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0

- Jürgen Osterhammel, Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview, Princeton, NJ: M. Wiener, 1997.

- Said, Edward, Orientalism, 1978; 25th-anniversary edition 2003 ISBN 978-0-394-74067-6

External links

- Liberal opposition to colonialism, imperialism and empire (pdf) - by professor Daniel Klein

- Colonialism entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy by Margaret Kohn

- Globalization (and the metaphysics of control in a free market world) - an online video on globalization, colonialism, and control.

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

...