Bayeux Tapestry

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

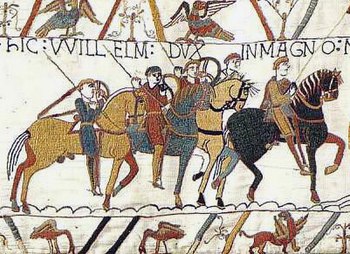

The Bayeux Tapestry (French: Tapisserie de Bayeux) is a 50 cm by 70 m (20 in by 230 ft) long embroidered cloth—not an actual tapestry—which explains the events leading up to the 1066 Norman invasion of England as well as the events of the invasion itself. The Tapestry is annotated in Latin. It is presently exhibited in a special museum in Bayeux, Normandy, France, with a Victorian replica in Reading, Berkshire, England.

Contents |

[edit] Origins of the Tapestry

Since the earliest known written reference to the tapestry is a 1476 inventory of Bayeux Cathedral, its origins have been the subject of much speculation and controversy.

French legend maintained the tapestry was commissioned and created by Queen Matilda, William the Conqueror's wife, and her ladies-in-waiting. Indeed, in France it is occasionally known as "La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde" (Tapestry of Matilda). However, scholarly analysis in the 20th century shows it probably was commissioned by William's half brother, Bishop Odo. The reasons for the Odo commission theory include: 1) three of the bishop's followers mentioned in Domesday Book appear on the tapestry; 2) it was found in Bayeux Cathedral, built by Odo; and 3) it may have been commissioned at the same time as the cathedral's construction in the 1070s, possibly completed by 1077 in time for display on the cathedral's dedication.

Assuming Odo commissioned the tapestry, it was probably designed and constructed in England by Anglo-Saxon artists given that Odo's main power base was in Kent, the Latin text contains hints of Anglo Saxon, other embroideries originate from England at this time, and the vegetable dyes can be found in cloth traditionally woven there.[1] [2] [3] Assuming this was the case, the actual physical work of stitching was most likely undertaken by skilled seamsters. Anglo-Saxon needlework, or Opus Anglicanum, was famous across Europe.

Alternative theories exist. Carola Hicks, in The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life of a Masterpiece (2006), has suggested it was commissioned by Edith of Wessex.[4] Wolfgang Grape, in his The Bayeux Tapestry: Monument to a Norman Triumph (1994), has challenged the consensus that the embroidery is Anglo-Saxon, distinguishing between Anglo-Saxon and other Northern European techniques;[5] however, textile authority Elizabeth Coatsworth refutes this argument.[6] George Beech, in his Was the Bayeux Tapestry Made in France? (1995), suggests the tapestry was executed at the Abbey of St. Florent in the Loire Valley, and says the detailed depiction of the Breton campaign argues for additional sources in France[7] Andrew Bridgeford in his book 1066: The Hidden History of the Bayeux Tapestry (2005), suggested that the tapestry was actually of English design and encoded with secret messages meant to undermine Norman rule.

[edit] Construction and technique

In common with other embroidered hangings of the early medieval period, this piece is conventionally referred to as a "tapestry," although it is not a true tapestry in which the design is woven into the cloth; it is in fact an embroidery.

The Bayeux tapestry is embroidered in wool yarn on a tabby-woven linen ground using two methods of stitching: outline or stem stitch for lettering and the outlines of figures, and couching or laid work for filling in figures.[3][2] The linen is assembled in panels and has been patched in numerous places.

The main yarn colours are terracotta or russet, blue-green, dull gold, olive green, and blue, with small amounts of dark blue or black and sage green. Later repairs are worked in light yellow, orange, and light greens.[2] Laid yarns are couched in place with yarn of the same or contrasting colour.

At the time of the Norman conquest of England, modern heraldry had not yet been developed. The knights in the Bayeux Tapestry carry shields, but there appears to have been no system of hereditary coats of arms. The beginnings of modern heraldic structure were in place, but would not become standard until the middle of the 12th century.

[edit] Modern history of the Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry was rediscovered in the late 18th century in Bayeux (where it had been traditionally displayed once a year at the Feast of the Relics), and engravings of it were published in the 1790s by Bernard de Montfaucon. Later, some people from Bayeux who were fighting for the Republic wanted to use it as a cloth to cover an ammunition wagon, but luckily a lawyer who understood its importance saved it and replaced it with another cloth.[8]

In 1803, Napoleon seized it and transported it to Paris. Napoleon wanted to use the tapestry as inspiration for his planned attack on England. When this plan was canceled, the tapestry was returned to Bayeux. The townspeople wound the tapestry up and stored it like a scroll. (Crack 1) After being seized by the Ahnenerbe, the tapestry spent much of World War II in the basement of the Louvre (Setton, 209). It is now protected on display in a museum in a dark room with special lighting behind sealed glass in order to minimize damage from light and air. In June 2007, the tapestry was listed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.

[edit] The plot of the Tapestry

The tapestry tells the story of the Norman conquest of England. The two combatants are the Anglo-Saxon English, led by Harold Godwinson, recently crowned as King of England (before that a powerful earl), and the Normans, led by William the Conqueror. The two sides can be distinguished on the tapestry by the customs of the day. The Normans shaved the back of their heads, while the Anglo-Saxons had mustaches.

The main character of the tapestry is William the Conqueror. William was the illegitimate son of Robert the Magnificent, Duke of Normandy, and Herleva (or Arlette), a tanner's daughter. She was later married off to another man and bore two sons, one of whom was Bishop Odo. When Duke Robert was returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, he was killed. William gained his father's title at a very young age and was a proven warrior at 19. He prevailed in the Battle of Hastings in October 1066 and captured the crown of England at 38. William knew little peace in his life. He was always doing battle, putting down rebel vassals or going to war with France. He was married to his distant cousin Matilda of Flanders.. (Barclay 31)

The tapestry begins with a panel of King Edward the Confessor, who has no son and heir. Edward appears to send Harold Godwinson, the most powerful earl in England to Normandy; the Tapestry does not specify why. When he arrives in Normandy, Harold is taken prisoner by Guy, Count of Ponthieu. William sends two messengers to demand his release, and Count Guy of Ponthieu quickly releases him to William. William, perhaps to impress Harold, invites him to come on a campaign against Conan II, Duke of Brittany. On the way, just outside the monastery of Mont St. Michel, two soldiers become mired in quicksand, and Harold saves the two Norman soldiers. William's army chases Conan from Dol de Bretagne to Rennes, and he finally surrenders at Dinan. William gives Harold arms and armour (possibly knighting him) and Harold takes an oath on saintly relics. It has been suggested, on the basis of the evidence of Norman chroniclers, that this oath was a pledge to support William's claim to the English throne, but the Tapestry itself offers no evidence of this. Harold leaves for home and meets again with the old king Edward, who appears to be remonstrating with Harold. Edward's attitude here is reprimanding towards Harold, and it has been suggested that he is admonishing Harold for making an oath to William. Edward dies, and Harold is crowned king. It is notable that in the Bayeux Tapestry, the ceremony is performed by Stigand, whose position as Archbishop of Canterbury was controversial. The Norman sources all name Stigand as the man who crowned Harold, in order to discredit Harold; the English sources suggest that he was in fact crowned by Aldred, making Harold's position as legitimate king far more secure.

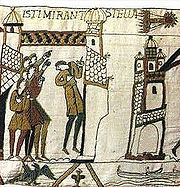

[edit] Halley's Comet

A star with streaming hair then appears: Halley's Comet. The first appearance of the comet would have been 24 April, nearly four months after Harold's coronation. Comets, in the beliefs of the Middle Ages, warned of impending doom. The news of Harold's coronation is taken to Normandy, where William then builds a fleet of ships. The invaders reach England, and land unopposed. William orders his men to find food, and a meal is cooked. A house is burnt, which may indicate some ravaging of the local countryside on the part of the invaders. News is brought to William, possibly about Harold's victory in the Battle of Stamford Bridge, although the Tapestry does not specify this. The Normans build a motte and bailey to defend their position. Messengers are sent between the two armies, and William makes a speech to prepare his army for battle.

The Battle of Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066. The English fight on foot behind a shield wall, whilst the Normans are on horses. The first to fall are named as Leofwine Godwinson and Gyrth Godwinson, Harold's brothers. Bishop Odo also appears in battle. The section depicting the death of Harold can be interpreted in different ways, as the name "Harold" appears above a lengthy death scene, making it difficult to identify which character is Harold. It is traditional that Harold is the figure with the arrow in his eye, but he could also be the figure just before with a spear through his chest, the character just after with his legs hacked off, or could indeed have suffered all three fates or none of them. The English then flee the field.

[edit] Mysteries of the tapestry

The tapestry contains several mysteries:

- There is a panel with what appears to be a clergyman touching or possibly striking a woman's face. No one knows the meaning of the inscription above this scene (ubi unus clericus et Ælfgyva, "where [we see] a certain cleric and Ælfgifu," a woman's name, although some authorities have claimed otherwise). There are two naked male figures in the border below this figure; the one directly below the figure is squatting and displaying prominent genitalia, a scene that was frequently censored in former reproductions. Historians speculate that it may represent a well known scandal of the day that needed no explanation (Setton 125).

- At least two panels of the tapestry are missing, perhaps even another 6.4 m (7 yards) worth. This missing area would probably include William’s coronation (a reconstruction of the missing panels - which show Duke William accepting the surrender of London and his coronation as King of England - was made by artist Jan Messent.)[9]

- The identity of Harold II of England in the vignette depicting his death is disputed. Some recent historians disagree with the traditional view that Harold II is the figure struck in the eye with an arrow. The view that it is Harold is supported by the fact that the words Harold Rex (King Harold) appear right above the figure's head. However, the arrow may have been a later addition following a period of repair. Evidence of this can be found in a comparison with engravings of the tapestry in 1729 by Bernard de Montfaucon, in which the arrow is absent. A figure is slain with a sword in the subsequent plate and the phrase above the figure refers to Harold's death (Interfectus est, "he is slain"). This would appear to be more consistent with the labeling used elsewhere in the work. However, needle holes in the linen suggest that, at one time, this second figure was also shown to have had an arrow in his eye. It was common medieval iconography that a perjurer was to die with a weapon through the eye. So, the tapestry might be said to emphasize William's rightful claim to the throne by depicting Harold as an oath breaker. Whether he actually died in this way remains a mystery and is much debated[citation needed].

- Above and below the illustrated story are to be found "the marginalia" i.e. background information for example showing the season of the year, the plundering of war booty and many symbols and pictures of uncertain significance.

[edit] Reliability

While political propaganda or personal emphasis may have somewhat distorted the historical accuracy of the story, the Bayeux tapestry presents a unique visual document of medieval arms, apparel, and other objects unlike any other artifact surviving from this period. Nevertheless, it has been noted that the warriors are depicted fighting with bare hands, while other sources indicate the general use of gloves in battle and hunt.

Also, the tapestry shows Harold enthroned with Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury, beside him, as though he has been crowned by him. Harold may have been crowned by Aldred of York, more likely than by Stigand, whose relationship with the papacy was tenuous. The tapestry ties a connection between Harold and the bishop, whether real or propaganda, making Harold's claim to the throne even weaker.

As the tapestry may have been made under Odo's command, it is possible he altered the story to benefit his half-brother William, perhaps by calling into doubt Harold's oath of loyalty.

[edit] Replicas

There are a number of replicas of the Bayeaux Tapestry in existence. A full-size replica of the Bayeux Tapestry was finished in 1886 and is exhibited in the Museum of Reading in Reading, Berkshire, England. Victorian morality required that a naked figure in the original tapestry (in the border below the Ælfgyva figure) be depicted wearing a brief garment covering his genitals. Starting in 2000, the Bayeux Group, part of the Viking Group Lindholm Høje, has been making an accurate replica of the Bayeux Tapestry in Denmark, using the original sewing technique, and natural plant-dyed yarn.

[edit] In popular culture

The tapestry was cited by Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics as an example of early narrative art[10] and British comic book artist Bryan Talbot has called it "the first known British comic strip."[11]

Because it resembles a movie storyboard and is widely recognised and, by modern standards at least, so distinctive in its artistic style, the Bayeux Tapestry has been used in a variety of different popular culture contexts. The tapestry has inspired later embroidery and artwork, particularly those involving invasions (such as the Overlord embroidery now at Portsmouth). It was also redone on the 15 July 1944 cover of the New Yorker magazine to commemorate D-Day. A number of films have used sections of the tapestry in their opening credits or closing titles, including: the Disney film Bedknobs and Broomsticks opening credit, Anthony Mann's El Cid, Zeffirelli's Hamlet, Frank Cassenti's La Chanson de Roland, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, and Richard Fleischer's The Vikings.[12]

On December 18, 2008 the popular game show Jeopardy! devoted an entire category to the tapestry. It was a video category, where two individuals in France presented the clues while referring to scenes on the tapestry.

The Bayeaux Tapestry has also worked its way into many memes, featuring popular internet catchphrases and slogans translated into Old English.

A novel by Adrien Goerz (Intrigue à l'anglaise, Grasset, 2007, ISBN 978-2-246-72391-2, no english translation at the moment) revolves around the tapestry. Without revealing the cunning plot, the author echoes an interesting theory about the purpose of the artwork. In his opinion, the linen scroll was made to be wrapped around a column for display on feast days, a temporary equivalent of Rome Trajan's_Column.

[edit] See also

[edit] Gallery

[edit] References

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage nomination form, in English and French. Word document. Published 09-05-2006.

- ^ a b c Wilson, David M.: The Bayeux Tapestry, Thames and Hudson, 1985, p.201-227

- ^ a b Coatsworth, Elizabeth: "Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon Embroidery", in Robin Netherton and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 1, Woodbridge, 2005, p. 1-27

- ^ "New Contender for The Bayeux Tapestry?", from the BBC, May 22, 2006. The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life of a Masterpiece, by Carola Hicks (2006). ISBN 0-7011-7463-3

- ^ See Grape, Wolfgang, The Bayeux Tapestry: Monument to a Norman Triumph, Prestel Publishing, 3791313657

- ^ "The attempt to distinguish Anglo-Saxon from other Northern European embroideries before 1100 on the grounds of technique cannot be upheld on the basis of present knowledge", Coatsworth, "Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon Embroidery", p.26

- ^ Beech, George: Was the Bayeux Tapestry Made in France?: The Case for St. Florent of Saumur. (The New Middle Ages), New York, Palgrave Macmillan 1995; reviewed in Robin Netherton and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 2, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, NY, the Boydell Press, 2006, ISBN 1843832038

- ^ "Episode 5589". Jeopardy!. 2008-12-18. No. 5589, season 25.

- ^ Messant, Jan (1999) (in English). Bayeux Tapestry Embroiderers' Story. Thirsk, UK: Madeira Threads (UK) Ltd. pp. 112. ISBN 0951634852 978-0951634851.

- ^ McCloud 1993. Understanding Comics pp.11-14

- ^ The History of the British Comic, Bryan Talbot, The Guardian Guide, September 8, 2007, page 5

- ^ "Re-embroidering the Bayeux Tapestry in Film and Media: The Flip Side of History in Opening and End Title Sequences". Richard Burt, University of Florida. 2007-08-18. http://www.clas.ufl.edu/~rburt/middleagesonfilm/bayeux1.html. Retrieved on 2007-08-31.

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 1, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, NY, the Boydell Press, 2005, ISBN 1843831236

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 2, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, NY, the Boydell Press, 2006, ISBN 1843832038

- Rud, Mogens, "The Bayeux Tapestry and the Battle of Hastings 1066" , Christian Eilers Publishers, Copenhagen 1992; contains full colour photographs and explanatory text

- Setton, Kenneth M., "900 Years Ago: the Norman Conquest", National Geographic Magazine (August 1966): 206–251; explains the Norman invasion and reproduces the tapestry in color; photographed by Milton A Ford and Victor R Boswell, Jr.

- Wilson, David M.: The Bayeux Tapestry, Thames and Hudson, 1985, ISBN 0500251223

[edit] Further reading

- Beech, George, Was the Bayeux Tapestry Made in France?: The Case for St. Florent of Saumur (The New Middle Ages), New York, Palgrave Macmillan 1995, ISBN1404966703

- Bridgeford, Andrew, 1066: The Hidden History in the Bayeux Tapestry, Walker & Company, 2005. ISBN 1841150401

- Burt, Richard, "Loose Threads: Weaving Around Women in the Bayeux Tapestry and Cinema," in Medieval Film, ed. Anke Bernau and Bettina Bildhauer (Manchester: Manchester UP, 2007).

- Foys, Martin K. Bayeux Tapestry Digital Edition. Individual licence ed; CD-ROM, 2003. ISBN 0-9539610-4-4

- Musset, Lucien (2005). The Bayeux Tapestry, translated by Richard Rex, Boydell Press

- Wilson, David McKenzie (Ed.). The Bayeux Tapestry : the Complete Tapestry in Color, Rev. ed. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004. ISBN 0-500-25122-3. ISBN 0-394-54793-4 (1985 ed.). LC NK3049.

- Wissolik, Richard David. "Duke William's Messengers: An Insoluble, Reverse-Order Scene of the Bayeux Tapestry." Medium Ævum. L (1982), 102–107.

- Wissolik, Richard David. "The Monk Eadmer as Historian of the Norman Succession: Korner and Freeman Examined." 'American Benedictine Review'. (March 1979), 32-42.

- Wissolik, Richard David. "The Saxon Statement: Code in the Bayeux Tapestry." Annuale Mediævale. 19 (September 1979), 69–97.

- Wissolik, Richard David. The Bayeux Tapestry. A Critical Annotated Bibliography with Cross References and Summary Outlines of Scholarship, 1729–1988. Greensburg: Eadmer Press, 1989.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Bayeux Tapestry |

- Bayeux Tapestry Museum

- Latin-English translation

- Bayeux Tapestry – Propaganda on cloth, "A World History of Art"

- The Bayeux Tapestry Story

- Britain's Bayeux Tapestry

- Create your own Bayeux Tapestry!