Tikal

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Tikal National Park* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|

|

| State Party | |

| Type | Mixed |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv, ix, x |

| Reference | 64 |

| Region** | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. |

|

Tikal (or Tik’al, according to the more current orthography) is one of the largest archaeological sites and urban centers of the Pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It is located in the archaeological region of the Petén Basin in what is now modern-day northern Guatemala. Situated in the department of El Petén at Coordinates: , the site is part of Guatemala's Tikal National Park and in 1979 was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The closest large modern settlements are Flores and Santa Elena, approximately 64 kilometres (40 mi) by road to the southwest.[1]

Tikal was one of the major cultural and population centers of the Maya civilization. Though monumental architecture at the site dates to the 4th century BC, Tikal reached its apogee during the Classic Period, ca. 200 to 900 AD, during which time the site dominated the Maya region politically, economically, and militarily while interacting with areas throughout Mesoamerica, such as central Mexican center of Teotihuacan. There is also evidence that Tikal was even conquered by Teotihuacan in the 4th century. [2] Following the end of the Late Classic Period, no new major monuments were built at Tikal and there is evidence that elite palaces were burned. These events were coupled with a gradual population decline, culminating with the site’s abandonment by the end of the 10th century.

Contents |

[edit] Site characteristics

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2008) |

[edit] Environmental setting

The ruins lie among lowland rainforest. Conspicuous trees at the Tikal park include gigantic ceiba (Ceiba pentandra) the sacred tree of the Maya; tropical cedar (Cedrela odorata), and mahogany (Swietenia). Regarding the fauna, agouti, coatis, gray foxes, spider monkeys, howler monkeys, harpy eagles, falcons, ocellated turkeys, guans, toucans, green parrots and leaf-cutting ants can be seen there regularly. Jaguars, jaguarundis, and cougars are also said to roam in the park. For centuries this city was completely covered under jungle.

The largest of the Classic Maya cities, Tikal had no water other than what was collected from rainwater and stored in underground storage facilities (termed chultuns). Archaeologists working in Tikal during the last century utilized the ancient underground facilities to store water for their own use. The absence of springs, rivers, and lakes in the immediate vicinity of Tikal highlights a prodigious feat: building a major city with only supplies of stored seasonal rainfall. Tikal prospered with intensive agricultural techniques, which were far more advanced than the slash and burn methods originally theorized by archeologists. The reliance on seasonal rainfall left Tikal vulnerable to prolonged drought, which is now thought to play a major role in the Classic Maya Collapse.

[edit] Etymology

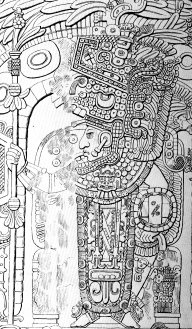

The name Tikal, 'place of the voices' in Itza Maya, is not the ancient name for the site but rather the name adopted shortly after its discovery in the 1840s (Drew 1999:136). Hieroglyphic inscriptions at the ruins refer to the central area of the ancient city as Yax Mutal or Yax Mutul. The kingdom as a whole was simply called Mutal or Mutul, which is the reading of the "hair bundle" Emblem Glyph seen in the accompanying photo. Its meaning remains obscure, although some scholars think that it is the hair knot of the Ahau or ruler.

[edit] The site

There are thousands of ancient structures at Tikal and only a fraction of these have been excavated, after decades of archaeological work. The most prominent surviving buildings include six very large Mesoamerican step pyramids, labeled Temples I - VI, each of which support a temple structure on their summits. Some of these pyramids are over 60 meters high (200 feet). They were numbered sequentially during the early survey of the site.

The majority of pyramids currently visible at Tikal were built during Tikal’s resurgence following the Tikal Hiatus (i.e., from the late 7th to the early 9th century). It should be noted, however, that the majority of these structures contain sub-structures that were initially built prior to the hiatus.

Temple I (also known as the Temple of Ah Cacao or Temple of the Great Jaguar) was built around C.E. 695; Temple II or the Moon Temple in C.E. 702; and Temple III in C.E. 810. The largest structure at Tikal, Temple IV, is approximately 70 meters (230 feet) tall. Temple IV marks the reign of Yik’in Chan Kawil (Ruler B, the son of Ruler A or Jasaw Chan K'awiil I) and two carved wooden lintels over the doorway that leads into the temple on the pyramid’s summit record a long count date (9.15.10.0.0) that corresponds to C.E. 741 (Sharer 1994:169). Temple V dates to about C.E. 750, and is the only one where no tomb has been found. Temple VI, also known as the Temple of the Inscriptions, was dedicated in C.E. 766.

Str. 5C-54, in the southwest portion of Tikal’s central core and west of Temple V, is known as the Lost World Pyramid. A 30 meter high "True Pyramid", with stairways in 3 sides and stucco masks, dating to the Late Preclassic, this pyramid is part of an enclosed complex of structures that remained intact through and un-impacted by later building activity at Tikal. The organization of this complex adheres to the themes defined for E-Groups.

The ancient city also has the remains of royal palaces, in addition to a number of smaller pyramids, palaces, residences, and inscribed stone monuments. There is even a building which seemed to have been a jail, originally with wooden bars across the windows and doors. There are also seven courts for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame, including a set of 3 in the "Seven Temples Plaza", a unique feature in Mesoamerica.

The residential area of Tikal covers an estimated 60 km² (23 square miles), much of which has not yet been cleared, mapped, or excavated. A huge set of earthworks has been discovered ringing Tikal with a 6 meter wide trench behind a rampart. Only some 9km of it has been mapped; it may have enclosed an area of some 125 km square (see below). Population estimates place the demographic size of the site between 100,000 and 200,000.

Recently, a project exploring the earthworks has shown that the scale of the earthworks is highly variable and that in many places it is inconsequential as a defensive feature. In addition, some parts of the earthwork were integrated into a canal system. The earthwork of Tikal varies significantly in coverage from what was originally proposed and it is much more complex and multifaceted than originally thought.

[edit] History

Tikal was a dominating influence in the southern Maya lowlands throughout most of the Early Classic. The site, however, was often at war and inscriptions tell of alliances and conflict with other Maya states, including Uaxactun, Caracol, Dos Pilas, Naranjo, and Calakmul. The site was defeated at the end of the Early Classic by Caracol, which rose to take Tikal's place as the paramount center in the southern Maya lowlands. It appears another defeat was suffered at the hands of Dos Pilas during the middle 7th century, with the possible capture and sacrifice of Tikal's ruler at the time (Sharer 1994:265).

[edit] Tikal hiatus

The "Tikal hiatus" refers to a period between the late 6th to late 7th century where there was a lapse in the writing of inscriptions and large-scale construction at Tikal. This hiatus in activity at Tikal was long unexplained until later epigraphic decipherments identified that the period was prompted by Tikal's comprehensive defeat at the hands of the Caracol polity in A.D. 562 after six years of warfare against an alliance of Calakmul, Dos Pilas and Naranjo. The hiatus at Tikal lasted up to the ascension of Jasaw Chan K'awiil I (Ruler A) in A.D. 682. In A.D. 695, Yukno’m Yich’Aak K’ahk’ of Calakmul (Kanal), was defeated by the new ruler of Tikal, Jasaw Chan K'awiil I, Nu’n U Jol Chaak’s heir. This defeat of Calakmul restored Tikal’s preeminence in the Central Maya region, but never again in the southwest Petén, where Dos Pilas maintained its presence.

The beginning of the Tikal hiatus has served as a marker by which archaeologists commonly sub-divide the Classic period of Mesoamerican chronology into the Early and Late Classic.[3]

[edit] Rulers

The known rulers of Tikal, with general or specific dates attributed to them, include the following:

[edit] Late Preclassic

- Yax Ehb' Xook – ca. A.D. 60, dynastic founder

- Siyaj Chan K'awil Chak Ich'aak ("Stormy Sky I") – ca. 2nd century

- Yax Ch’aktel Xok – ca. 200

[edit] Early Classic

- Balam Ajaw ("Decorated Jaguar") – A.D. 292

- K'inich Ehb' – ca. A.D. 300

- Siyaj Chan K'awiil I - ca. A.D. 307

- Ix Une' B'alam ("Queen Jaguar") – A.D. 317

- "Leyden Plate Ruler" – A.D. 320

- K'inich Muwaan Jol – died A.D. 359

- Chak Tok Ich'aak I ("Jaguar Paw I") – c.a. 360-378. His palace, unusually, was never built over by later rulers, and was kept in repair for centuries as an apparent revered monument. He died on the same day that Siyah K'ak' arrived in Tikal, probably executed by the Teotihuacano conquerors.

- Nun Yax Ayin – A.D. 379-411. Nun Yax Ayin was a noble from Teotihuacan who was installed on Tikal's throne in 379 by Siyaj K'ak'.

- Siyaj Chan K'awiil II ("Stormy Sky II") – A.D. 411-456.

- K'an-Ak ("Kan Boar") – A.D. 458-486.

- Ma'Kin-na Chan – ca. late 5th century.

- Chak Tok Ich'aak II (Bahlum Paw Skull) – A.D. 486-508. Married to "Lady Hand"

- Ix Kalo'mte' Ix Yo K'in ("Lady of Tikal") – A.D. 511-527. Co-ruled with Kaloomte' B'alam, possibly as consort.

- Kaloomte' B'alam ("Curl-Head" and "19th Lord") – A.D. 511-527. Co-ruled with Ix Kalo'mte' Ix Yo K'in ("Lady of Tikal"), as regent.

- "Bird Claw" ("Animal Skull I", "Ete I") – ca. A.D. 527–537.

- Wak Chan K'awiil ("Double-Bird") – A.D. 537-562. Capture and possible sacrifice by Caracol.

- "Lizard Head II" – Unknown, lost a battle with Caracol in A.D. 562.

[edit] Hiatus

- K'inich Waaw ("Animal Skull") – A.D. 593-628.

- K'inich Wayaan – ca. early/mid 7th century.(probably same as proceeding)

- K'inich Muwaan Jol II – ca. early/mid 7th century. 628- abt 647 ?

Lak Nam K`awaill killed 648, Balaj Chan K`awaill, ajaw of Dos Pilas then claimed rulership of Tikal againest Nuun Ujol Chaak ,normally called ruler of Tikal 648- ?679 Balaj Chan K`awaill and Nuun Ujol Chaak are apparently sons of K`inich Muwaan Jol II, He being named as such by Balaj Chan Kawaill and a pottery shard has been recovered at the Tikal site calling Nuun Ujol Chaak son of Muwaan Jol.

[edit] Late Classic

- Jasaw Chan K'awiil I (a.k.a. Ruler A or Ah Cacao) – A.D. 682-734. Entombed in Temple I. His queen Lady Twelve Macaw (died A.D. 704) is entombed in Temple II. Triumphed in war with Calakmul in A.D. 711.

- Yik'in Chan K'awiil (a.k.a. Ruler B) – A.D. 734-766. His wife was Shana'Kin Yaxchel Pacal "Green Jay on the Wall" of Lakamha. It is unknown exactly where his tomb lies, but strong archaeological parallels between Burial 116 (the resting place of his father) and Burial 196, located in the diminutive pyramid immediately south of Temple II and referred to as Str. 5D-73, suggest the latter may be the tomb of Yik’in Chan Kawil (Sharer 1994:169). Other possible locations, and likely candidates as mortuary shrines, include Temples IV and VI.

- "Temple VI Ruler" – A.D. 766-768

- Yax Nuun Ayiin II ("Chitam") – A.D. 768-790

- Chitam II ("Dark Sun") – Buried ca. A.D. 810 Buried in Temple III

- "Jewel K'awil" – A.D. 849

- Jasaw Chan K'awiil II – A.D. 869-889

Note: English language names are provisional nicknames based on their identifying glyphs, where rulers' Maya language names have not yet been definitively deciphered phonetically.

[edit] Modern history

As is often the case with huge ancient ruins, knowledge of the site was never completely lost in the region. Some second- or third-hand accounts of Tikal appeared in print starting in the 17th century, continuing through the writings of John Lloyd Stephens in the early 19th century (Stephens and his illustrator Frederick Catherwood heard rumors of a lost city, with white building tops towering above the jungle, during their 1839-40 travels in the region). Due to the site's remoteness from modern towns, however, no explorers visited Tikal until Modesto Méndez and Ambrosio Tut visited it in 1848. Several other expeditions came to further investigate, map, and photograph Tikal in the 19th century (including Alfred P. Maudslay in 1881-82) and the early 20th century.

In 1951, a small airstrip was built at the ruins, which previously could only be reached by several days’ travel through the jungle on foot or mule. From 1956 through 1970, major archeological excavations were made by the University of Pennsylvania. In 1979, the Guatemalan government began a further archeological project at Tikal, which continues to this day.

[edit] Popular culture

- Tikal was used as background scenery of the Rebel base on Yavin 4 in the film Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope.

- The character Tikal the Echidna from the videogame Sonic Adventure is named after the ruins, and several areas in the game are designed based on the ruins.

- Tikal is a level of the game of Fantastic Four

- Tikal is the name of a board game by Rio Grande Games.

- The song Temple of the Cat by musician Arjen Anthony Lucassen makes reference to the Jaguar Temple and the city of Tikal. Samples on the song come from a Maya festival.

- Tikal appears in the videogame Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis.

- Tikal is the title of second song on E.S. Posthumus' album Unearthed.

- One of the Temples of Tikal features as a Wonder in the computer game Rise of Nations.

- Tikal appears as exterior of Drax's pyramid headquarters in the Amazon rainforest in Moonraker (film).

[edit] Selected images

|

Large stone mask at the North Acropolis complex, representing the Principal Bird Deity.[4] |

Photo-textured Laser scan elevation of Tikal's Temple II, showing measurements and dimensions for this Step pyramid. |

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Kelly (1996), pp.111–112

- ^ Martin & Grube (2008),pp.29–32

- ^ Miller and Taube (1993), p.20.

- ^ See annotations of the equivalent images of this mask, Nos. 7909A, 7909B, 7909C, at the Justin Kerr Precolumbian Portfolio (Kerr n.d.)

[edit] References

- Coe, Michael D. (1987). The Maya. Ancient peoples and places series (4th edition (revised) ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27455-X. OCLC 15895415.

- Drew,David (1999). The Lost Chronicles of the Mayan Kings. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Gill, Richardson B. (2000). The Great Maya Droughts: Water, Life, and Death. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-826-32194-1. OCLC 43567384.

- Harrison, Peter D. (2006). "Maya Architecture at Tikal". in Nikolai Grube (ed.). Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Köln: Könemann. pp. 218–231. ISBN 3-8331-1957-8. OCLC 71165439.

- Kelly, Joyce (1996). An Archaeological Guide to Northern Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2858-5. OCLC 34658843.

- Kerr, Justin (n.d.). "A Precolumbian Portfolio" (online database). FAMSI Research Materials. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. http://research.famsi.org/kerrportfolio.html. Retrieved on 2007-06-13.

- Martin, Simon; and Nikolai Grube (2008). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya (2nd edn (revised) ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28726-2. OCLC 191753193.

- Miller, Mary; and Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

- Sharer, Robert J. (1994). The Ancient Maya (5th edition (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2130-0. OCLC 28067148.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Tikal |

- Tikal Digital Media Archive (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), focused in the area around the Great Plaza and Temple IV with data from a UC Berkeley/CyArk research partnership

- Park description and photo gallery

- Tikal at the Open Directory Project

- History of Rediscovery and Archaeological Work at Tikal at Mesoweb

- Tikal UNESCO Designation

- Virtual Tour of Tikal on Roundus