Aryan

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- In common European language usage, the Nazi German notion of what constitutes an 'Aryan' has overtaken all other uses of the term.

- The term does however survive in academic, and in indigenous Iranian and Indian usage. It is a ethno-linguonym in academic and Iranian usage, but has acquired other significance in Indian usage.

Aryan (IPA: /'ərɪən/) is an English language loanword. As the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language states at the beginning of its definition, "[it] is one of the ironies of history that Aryan, a word nowadays referring to the blond-haired, blue-eyed physical ideal of Nazi Germany, originally referred to a people who looked vastly different. Its history starts with the ancient Indo-Iranians, peoples who inhabited parts of what are now Iran, Afghanistan, and India."[1]

As an adaptation of the Latin Arianus, referring to Iran, 'Aryan' has "long been in English language use".[2] Its history as a loan word began in the late 1700s, when the word was borrowed from Sanskrit ā́rya- to mean the same thing it originally did in that Old Indic language, namely as a (self-)identifier of speakers of North Indian languages.[2] When it was determined that Iranian languages – both living and ancient – used a similar term in much the same way (but in the Iranian context as a self-identifier of Iranian peoples), it became apparent that the shared meaning had to derive from the ancestor language of the shared past, and so, by the early 1800s, the word 'Aryan' came to refer the group of languages deriving from that ancestor language, and by extension, the speakers of those languages.[3]

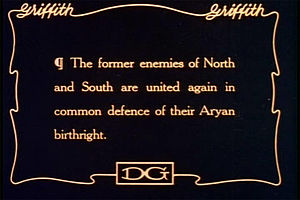

Then, in the 1830s, the term "Aryan" was adopted for speakers of Indo-European languages in general, in the erroneous belief that this was an ethnic self-identifier used by prehistoric speakers of European languages. This development was in turn instrumental to the development of the concept of an "Aryan race", which by the early 20th century became closely linked to Nordicism, which posited Northern European racial superiority over all other peoples (including Indians and Iranians). In Nazi Germany the classification of peoples as Aryan or not was most emphatically directed towards the exclusion of Jews.[4][n 1] This racialist interpretation engendered both the "Aryanization" programs of Nazi Germany, and – in a late 19th century British-mediated form – to a racialist reinterpretation of Indian society, texts and history. Following the end of World War II and the discovery of the genocide that the self-styled "Aryans" had caused, the word 'Aryan' ceased to have a positive meaning in general Western understanding. In colloquial modern English it is typically used to signify the Nordic racial ideal promoted by the Nazis.

In present-day India, the original ethno-linguistic signifier has been mostly lost, the denotation having been semantically replaced by other, secondary, meanings. In Iran, the original self-identifier lives on in ethnic names like "Alani", "Ir", and in the name of Iran itself.[5] In present-day academia, the terms "Indo-Iranian" and "Indo-European" have made most uses of the term 'Aryan' obsolete, and 'Aryan' is now mostly limited to its appearance in the term "Indo-Aryan" to represent (speakers of) North Indian languages. Notions of an "Aryan race" only survive in the context of fascist nationalism, in which nationhood is defined by ancestry.

Contents |

History

Before the 19th century

This particular example is said to date from the 1st millennium BCE. It was found near Gilan, Iran, and is now at the National Museum of Iran.

The meaning of 'Aryan' that entered the English language in the late 1700s was the one associated with the technical term used in comparative philology, which in turn had the same meaning as that evident in the very oldest Old Indic usage, i.e. as a (self-)identifier of "(speakers of) North Indian languages".[2][n 2] This usage was simultaneously influenced by a word that appeared in classical sources (Latin and Greek Arianes, e.g. in Pliny 1.133 and Strabo 15.2.1-8), and recognized to be the same as that which appeared in living Iranian languages, where it was a (self-)identifier of the "(speakers of) Iranian languages". Accordingly, 'Aryan' came to refer to the languages of the Indo-Iranian language group, and by extension, speakers of those languages.[8]

19th century

In the 19th century, linguists still supposed that the age of a language determined its "superiority" (because it was assumed to have genealogical purity). Then, based on the (now known to be erroneous) assumption that Sanskrit was the oldest Indo-European language, and the (now known to be untenable) position that Irish Éire was etymologically related to "Aryan", in 1837 Adolphe Pictet popularized the idea that the term "Aryan" could also be applied to the entire Indo-European language family as well. The groundwork for this had been laid in 1808, "when Friedrich Schlegel, a German scholar who was an important early Indo-Europeanist, came up with a theory that linked the Indo-Iranian words with the German word Ehre, 'honor', and older Germanic names containing the element ario-, such as the Swiss warrior Ariovistus who was written about by Julius Caesar. Schlegel theorized that far from being just a designation of the Indo-Iranians, the word *arya- had in fact been what the Indo-Europeans called themselves, meaning [so Schlegel] something like 'the honorable people.' (This theory has since been called into question.)"[1]

Following this linguistic argument, in the 1850s Arthur de Gobineau supposed that "Aryan" corresponded to the suggested prehistoric Indo-European culture (1853-1855, Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races). Further, de Gobineau believed that there were three basic races – white, yellow and black – and that everything else was caused by race miscegenation, which de Gobineau argued was the cause of chaos. The "master race", so de Gobineau, were the Northern European "Aryans", who had remained "racially pure". Southern Europeans (to include Spaniards and Southern Frenchmen), Eastern Europeans, North Africans, Middle Easterners, Iranians, Central Asians, Indians, he all considered racially mixed, degenerated through the miscegenation, and thus less than ideal.

In 19th century Indo-European studies, the language of the Rigveda was the most archaic Indo-European language known to scholars, indeed the only records of Indo-European that could reasonably claim to date to the Bronze Age. This "primacy" of Sanskrit inspired some scholars, such as Friedrich Schlegel, to assume that the locus of the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat had been in India, with the other dialects spread to the west by historical migration. This was however never a mainstream position even in the 19th century. Most scholars assumed a homeland either in Europe or in Western Asia, and Sanskrit must in this case have reached India by a language transfer from west to east, in a movement described in terms of "invasion" by Max Müller (see Indo-Aryan migration).

By the 1880s a number of linguists and anthropologists argued that the "Aryans" themselves had originated somewhere in northern Europe. A specific region began to crystallize when the linguist Karl Penka (Die Herkunft der Arier. Neue Beiträge zur historischen Anthropologie der europäischen Völker, 1886) popularized the idea that the "Aryans" had emerged in Scandinavia, and could be identified by the distinctive Nordic characteristics of blond hair and blue eyes. The distinguished biologist Thomas Henry Huxley agreed with him, coining the term "Xanthochroi" to refer to fair-skinned Europeans (as opposed to darker Mediterranean peoples, who Huxley called "Melanochroi").[9]

This "Nordic race" theory gained traction following the publication of Charles Morris's The Aryan Race (1888), which argued that the "original Aryans" could be identified by their blond hair and other Nordic features, such as dolichocephaly (long skull). A similar rationale was followed by Georges Vacher de Lapouge in his book L'Aryen et son rôle social (1899, "The Aryan and his Social Role"), in which the French anthropologist argued that the "dolichocephalic-blond" peoples were natural leaders, destined to rule over more brachiocephalic (short-skulled) peoples. Archetypes of these short-skulled people, so Vacher de Lapouge, were the Jews.[10] To this idea of "races", Vacher de Lapouge espoused what he termed selectionism, and which had two aims: first, achieving the annihilation of trade unionists, considered "degenerate"; second, the prevention of labour dissatisfaction through the creation of "types" of man, each "designed" for one specific task.

Meanwhile, in India, the British colonial government had followed de Gobineau's arguments along another line, and had fostered the idea of a superior "Aryan race" that co-opted the Indian caste system in favor of imperial interests.[11][12] In its fully developed form, the British-mediated interpretation foresaw a segregation of Aryan and non-Aryan along the lines of caste, with the upper castes being "Aryan" and the lower ones being "non-Aryan". The European developments not only allowed the British to identify themselves as high-caste, but also allowed the Brahmans to view themselves as on-par with the British. Further, it provoked the reinterpretation of Indian history in racialist and Hindu nationalist terms,[11][12] and – in following a special interpretation of Max Müller's identification of "Aryan" as a national name – gave rise to the so-called "Out of India" theory, which sought an Indian origin of the Indo-European "Aryans".

The racialist ideas that were developing independently in India and Europe fused in esoterica. In The Secret Doctrine (1888), Helena Petrovna Blavatsky saw the "Aryans" as the fifth of her seven "Root Races", dating them to about a million years ago, and tracing them to Atlantis. She considered "Abraham" to be a corruption of a word meaning "No Brahmin", from whom the Semites – "degenerate in spirituality and perfected in materiality" – had descended, and who were one rung down on the Root Race scale. The Jews, so Blavatsky, were a "tribe descended from the Tchandalas of India, the outcasts".

In Iran, racialist rhetoric became a literary idiom during the 7th century, i.e. in the aftermath of the Islamic conquest, when the Arabs became the primary "Other" – the anaryas – and the antithesis of everything Iranian (i.e. Aryan) and Zoroastrian. But "the antecedents of [present-day] Iranian ultra-nationalism can be traced back to the writings of late nineteenth-century figures such as Mirza Fath Ali Akhunzadeh and Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani. Demonstrating affinity with Orientalist views of the supremacy of the 'Indo-European peoples' and the mediocrity of the 'Semitic race,' Iranian nationalist discourse idealized pre-Islamic [Achaemenid and Sassanid] empires, whilst negating the 'Islamization' of Persia by Muslim forces."[13] In the 20th century, different aspects of this idealization of a distant past would be instrumentalized by both the Pahlavi monarchy, and by the Islamic republic that followed it; the Pahlavis used it as a foundation for anticlerical monarchism, and the clerics used it to exalt Iranian values vis-á-vis westernization.[14]

20th century

Back in Europe, in a summary of the status-quo, Hermann Hirt (1905, Die Indogermanen - Hirt consistently used Indogermanen, not Arier, to refer to the Indo-Europeans) asserted that there was no longer any question that the plains of northern Germany were the Urheimat (p. 197) of the Indo-European languages, and he connecting the "blond type" (p. 192) with the core population of the early, "pure" Indo-Europeans. The identification of the Indo-Europeans with the north German Corded Ware culture bolstered this position. First proposed by Gustaf Kossinna in 1902, it gained currency over the following two decades, until Vere Gordon Childe concluded that "the Nordics' superiority in physique fitted them to be the vehicles of a superior language" (1926, The Aryans: a study of Indo-European origins).

Gordon Childe would later regret having expressed that idea, but the depiction as possessors of a "superior language" became a matter of national pride in learned circles of Germany. Against the background of the lost World War I (portrayed to have been lost because Germany had been betrayed from within – miscegenation was at fault, more evidence for which was seen in the "corruption" represented by socialist trade unionists and other "degenerates"), Alfred Rosenberg asserted that there was a "racial threat" to Germany's homogeneous "Aryan-Nordic" (arisch-nordisch) or "Nordic-Atlantean" (nordisch-atlantisch, cf. Blavatsky above) civilization. In Rosenberg's view, the "racial threat" was "Jewish-Semitic race" (jüdisch-semitisch Rasse). Where Germany's homogeneous people were a "master race" capable of, or with an interest in, creating and maintaining culture, other "races" were merely capable of conversion, or destruction of culture.

Rosenberg – one of the principal architects of Nazi ideological creed – argued for a new "religion of the blood," based on the supposed innate promptings of the Nordic soul to defend its "noble" character against racial and cultural degeneration. Under Rosenberg, the theories of Arthur de Gobineau, Georges Vacher de Lapouge, Blavatsky, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Madison Grant, and those of Hitler ("the exact opposite of the Aryan is the Jew") all culminated in Nazi Germany's race policies and the "Aryanization" decrees of the 1920s, 1930s, and early 1940s. In its "apalling medical model", the annihilation of the "racially inferior" Untermenschen was sanctified as the excision of a diseased organ in an otherwise healthy body.[15]

Following the end of World War II and the discovery of the genocide that the "master race" had caused, the word "Aryan" ceased to have any positive meaning in Western understanding. By then, the term "Indo-Iranian" and "Indo-European" had made most uses of the term "Aryan" superfluous, and "Aryan" now survives only in the term "Indo-Aryan" to indicate (speakers of) North Indian languages. Indo-Aryan and Aryan may not however be equated; such an equation is not supported by the historical evidence.[16]

The use of the term to designate speakers of all Indo-European languages is now considered an "aberration" to be avoided.[17] Notions of an elite "Aryan race" only survive in nationalist contexts, to include White nationalism, Indian nationalism and Iranian nationalism. Echoes of "the 19th century prejudice about 'northern' Aryans who were confronted on Indian soil with black barbarians [...] can still be heard in some modern studies."[16]

Notes

- ^ Under the 1933 Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, a non-Aryan was defined as "an individual descended from a non-Aryan (in particular Jewish parents or grandparents)" (Campt 2004, p. 143).

- ^ The context being religious, Max Müller understood this to especially mean "the worshipers of the gods of the Brahmans". If this is seen from the point of view of the religious poets of the RigVedic hymns, an 'Aryan' was then a person who held the same religious convictions as the poet himself. This idea can then also be found in Iranian texts. Müller took Aryan to be an exclusively linguistic term and remarked in his Biography of words (pp. 120-1): "To me an ethnologist who speaks of Aryan race, Aryan blood, Aryan eyes and Aryan hair, is as great a sinner as a linguist who speaks of a dolichocephalic dicitionary or a brachycephalic grammar. Aryan, in scientific language, is utterly inapplicable to race. It means language and nothing but language, and if we speak of Aryan race at all, we should know that it means no more than x + Aryan speech."

References

- ^ a b Watkins, Calvert (2000), "Aryan", American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.), New York: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-82517-2.

- ^ a b c Simpson, John Andrew; Weiner, Edmund S. C., eds. (1989), "Aryan, Arian", Oxford English Dictionary, I (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, p. 672, ISBN 0-19-861213-3.

- ^ Bailey, Harold Walter (1989), "Arya", Encyclopedia Iranica, 2, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v2f7/v2f7a004.html.

- ^ Campt, Tina (2004), Other Germans: Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender, and Memory in the Third Reich, University of Michigan Press, p. 143.

- ^ Schmitt, Rüdiger (1989), "Aryan", Encyclopedia Iranica, 2, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v2f7/v2f7a010.html.

- ^ Wilson, Thomas (1894), Swastika the Earliest Known Symbol and Its Migrations: The Earliest Known Symbol, and Its Migrations, Report of the U. S. National Museum, p. 770.

- ^ cf. Gershevitch, Ilya (1968), "Old Iranian Literature", Handbuch der Orientalistik, Literatur I, Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–31, p. 2.

- ^ Siegert, Hans (1941-1942), "Zur Geschichte der Begriffe 'Arier' und 'Arisch'", Wörter und Sachen, New Series 4: 84–99.

- ^ Huxley, Thomas (1890), The Aryan Question and Pre-Historic Man, , Nineteenth Century (XI/1890).

- ^ Vacher de Lapouge, Georges; Clossen, C., trans. (1899), "Old and New Aspects of the Aryan Question", The American Journal of Sociology 5 (3): 329–346, doi:.

- ^ a b Thapar, Romila (1996), "The Theory of Aryan Race and India: History and Politics", Social Scientist 24 (1/3): 3–29, doi:.

- ^ a b Leopold, Joan (1974), "British Applications of the Aryan Theory of Race to India, 1850-1870", The English Historical Review 89 (352): 578–603, doi:.

- ^ Adib-Moghaddam, Arshin (2006), "Reflections on Arab and Iranian Ultra-Nationalism", Monthly Review Magazine 11/06, http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/aam201106.html.

- ^ Keddie, Nikki R.; Richard, Yann (2006), Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution, Yale University Press, pp. 178f., ISBN 0-300-12105-9.

- ^ Glover, Jonathan (1998), "Eugenics: Some Lessons from the Nazi Experience", in Harris, John; Holm, Soren, The Future of Human Reproduction: Ethics, Choice, and Regulation, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 57–65.

- ^ a b Kuiper, B.F.J. (1991), Aryans in the Rigveda, Leiden Studies in Indo-European, Amsterdam: Rodopi, ISBN 90-5183-307-5.

- ^ Witzel, Michael (2001), "Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts", Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7 (3): 1–115.

- Ivanov, Vyacheslav V.; Gamkrelidze, Thomas (1990), "The Early History of Indo-European Languages", Scientific American 262 (3): 110116.

- Arvidsson, Stefan; Wichmann, Sonia (2006), Aryan Idols: Indo-European Mythology as Ideology and Science, University of Chicago Press.

- Poliakov, Leon (1996), The Aryan Myth: A History of Racist and Nationalistic Ideas In Europe, New York: Barnes & Noble Books, ISBN 0-7607-0045-6.