Athanasius Kircher

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article is missing citations or needs footnotes. Please help add inline citations to guard against copyright violations and factual inaccuracies. (September 2007) |

| Athanasius Kircher | |

Portrait of Kircher from Mundus Subterraneus, 1664

|

|

| Born | 2 May 1601 or 1602 Geisa, Abbacy of Fulda |

|---|---|

| Died | 27 November or 28 November 1680 Rome |

| Nationality | German |

| Religious beliefs | Roman Catholicism (Jesuit scientist-priest)[1] |

Athanasius Kircher (sometimes erroneously spelled Kirchner) was a 17th century German Jesuit scholar who published around 40 works, most notably in the fields of oriental studies, geology, and medicine. He also invented the first megaphone.

He made an early study of Egyptian hieroglyphs, and has been considered the founder of Egyptology.[1] One of the first people to observe microbes through a microscope, he was thus ahead of his time in proposing that the plague was caused by an infectious microorganism and in suggesting effective measures to prevent the spread of the disease.

Kircher has been compared to Leonardo da Vinci for his inventiveness and the breadth and depth of his work. A scientific star in his day, towards the end of his life he was eclipsed by the rationalism of René Descartes and others. In the late 20th century, however, the aesthetic qualities of his work again began to be appreciated. One scholar, Edward W. Schmidt, has called him "the last Renaissance man".

Contents |

[edit] Life

Kircher was born on 2 May in either 1601 or 1602 (he himself did not know) in Geisa, Buchonia, near Fulda, currently Hesse, Germany. From his birthplace he took the epithets Bucho, Buchonius and Fuldensis which he sometimes added to his name. He attended the Jesuit College in Fulda from 1614 to 1618, when he joined the order himself as a seminarian.

The youngest of nine children, Kircher was a precocious youngster who was taught Hebrew by a rabbi[citation needed]in addition to his studies at school. He studied philosophy and theology at Paderborn, but fled to Cologne in 1622 to escape advancing Protestant forces.[citation needed] On the journey, he narrowly escaped death after falling through the ice crossing the frozen Rhine— one of several occasions on which his life was endangered. Later, travelling to Heiligenstadt, he was caught and nearly hanged by a party of Protestant soldiers.[citation needed]

At Heiligenstadt, he taught mathematics, Hebrew and Syriac, and produced a show of fireworks and moving scenery for the visiting Elector Archbishop of Mainz, showing early evidence of his interest in mechanical devices. He joined the priesthood in 1628 and became professor of ethics and mathematics at the University of Würzburg, where he also taught Hebrew and Syrian. From 1628, he also began to show an interest in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Kircher published his first book (the Ars Magnesia, reporting his research on magnetism) in 1631, but the same year he was driven by the continuing Thirty Years' War to the papal University of Avignon in France. In 1633, he was called to Vienna by the emperor to succeed Kepler as Mathematician to the Habsburg court. On the intervention of Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, the order was rescinded and he was sent instead to Rome to continue with his scholarly work, but he had already set off for Vienna.

On the way, his ship was blown off-course and he arrived in Rome before he knew of the changed decision. He based himself in the city for the rest of his life, and from 1638, he taught mathematics, physics and oriental languages at the Collegio Romano for several years before being released to devote himself to research. He studied malaria and the plague, amassing a collection of antiquities, which he exhibited along with devices of his own creation in the Museum Kircherianum.

In 1661, Kircher discovered the ruins of a church said to have been constructed by Constantine on the site of Saint Eustace's vision of Jesus Christ in a stag's horns. He raised money to pay for the church’s reconstruction as the Santuario della Mentorella, and his heart was buried in the church on his death.

[edit] Works

Kircher published a large number of substantial books on a very wide variety of subjects, such as Egyptology, geology, and music theory. His syncretic approach paid no attention to the boundaries between disciplines which are now conventional: his Magnes, for example, was ostensibly a discussion of magnetism, but also explored other forms of attraction such as gravity and love. Perhaps Kircher's best-known work today is his Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652–54) a vast study of Egyptology and comparative religion. His books, written in Latin, had a wide circulation in the 17th century, and they contributed to the dissemination of scientific information to a broader circle of readers. But Kircher is not now considered to have made any significant original contributions, although a number of discoveries and inventions (e.g., the magic lantern) have sometimes been mistakenly attributed to him.[2]

[edit] Egyptology

Kircher was acknowledged as his era's greatest student of Ancient Egypt. While some of his notions are long discredited, portions of his work have been valuable to later scholars; Kircher helped pioneer Egyptology as a field of serious study.

Kircher's interest in Egyptology began in 1628 when he became intrigued by a collection of hieroglyphs in the library at Speyer. He learned Coptic in 1633 and published the first grammar of that language in 1636, the Prodromus coptus sive aegyptiacus. In the Lingua aegyptiaca restituta of 1643, he argued that Coptic was not a separate language, but the last development of ancient Egyptian. He also recognised the relationship between the hieratic and hieroglyphic scripts.

In Oedipus Aegyptiacus he argued, under the impression of the Hieroglyphica, that ancient Egyptian was the language spoken by Adam and Eve, that Hermes Trismegistus was Moses, and that hieroglyphs were occult symbols which "cannot be translated by words, but expressed only by marks, characters and figures." This led him to translate simple hieroglyphic texts now known to read as dd Wsr ("Osiris says") as "The treachery of Typhon ends at the throne of Isis; the moisture of nature is guarded by the vigilance of Anubis"[citation needed]. Kircher apparently fooled himself (as well as some contemporaries) into believing that he could read the hieroglyphics, but his "translations" were largely figments of his own imagination, having little to do with the actual text.

Although his approach to deciphering the texts was based on a fundamental misconception, Kircher did pioneer serious study of hieroglyphs, and the data which he collected were later used by Champollion in his successful efforts to decode the script. Kircher himself was alive to the possibility of the hieroglyphs constituting an alphabet; he included in his proposed system (incorrect) derivations of the Greek alphabet from 21 hieroglyphs. He was actively involved in the erection of Obelisks on Roman squares, often adding fantastic "hieroglyphs" of his own design in the blank areas that are now puzzling to modern scholars.

[edit] Sinology

Kircher had an early interest in China, telling his superior in 1629 that he wished to become a missionary to the country. His China Illustrata (1667) was an encyclopedia of China, which combined accurate cartography with mythical elements, such as dragons. The work emphasised the Christian elements of Chinese history, both real and imagined: he noted the early presence of Nestorians, but also claimed that the Chinese were descended from the sons of Ham, that Confucius was Hermes Trismegistus/Moses and that the Chinese characters were corrupted hieroglyphs. In his system, ideograms were inferior to hieroglyphs because they referred to specific ideas rather than to mysterious complexes of ideas, while the signs of the Maya and Aztecs were yet lower pictograms which referred only to objects. Umberto Eco comments that this idea reflected and supported the European attitude to the Chinese and native American civilisations;

"China was presented not as an unknown barbarian to be defeated but as a prodigal son who should return to the home of the common father". (p. 69)

[edit] Geology

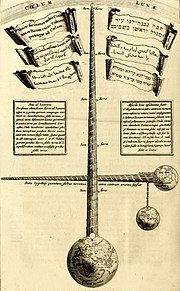

On a visit to southern Italy in 1638, the ever-curious Kircher was lowered into the crater of Vesuvius, then on the brink of eruption, in order to examine its interior. He was also intrigued by the subterranean rumbling which he heard at the Strait of Messina. His geological and geographical investigations culminated in his Mundus Subterraneus of 1664, in which he suggested that the tides were caused by water moving to and from a subterranean ocean.

Kircher was also puzzled by fossils. He understood that some were the remains of animals which had turned to stone, but ascribed others to human invention or to the spontaneous generative force of the earth. He ascribed large bones to giant races of humans.[3] Not all the objects which he was attempting to explain were in fact fossils, hence the diversity of explanations.

[edit] Medicine

Kircher took a notably modern approach to the study of diseases, as early as 1646 using a microscope to investigate the blood of plague victims. In his Scrutinium Pestis of 1658, he noted the presence of "little worms" or "animalcules" in the blood, and concluded that the disease was caused by microorganisms. The conclusion was correct, although it is likely that what he saw were in fact red or white blood cells and not the plague agent, Yersinia pestis. He also proposed hygienic measures to prevent the spread of disease, such as isolation, quarantine, burning clothes worn by the infected and wearing facemasks to prevent the inhalation of germs.

[edit] Display of screen images

In 1646, Kircher published Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae, on the subject of the display of images on a screen using an apparatus similar to the magic lantern as developed by Christian Huygens and others. Kircher described the construction of a "catotrophic lamp" that used reflection to project images on the wall of a darkened room. Although Kircher did not invent the device, he made improvements over previous models, and suggested methods by which exhibitors could use his device. Much of the significance of his work arises from Kircher's rational approach towards the demystification of projected images.[4] Previously such images had been used in Europe to mimic supernatural appearances (Kircher himself cites the use of displayed images by the rabbis in the court of King Solomon). Kircher stressed that exhibitors should take great care to inform spectators that such images were purely naturalistic, and not magical in origin.

[edit] Other

Kircher constructed a magnetic clock, the mechanism of which he explained in his Magnes (1641). The device had originally been invented by another Jesuit, Fr. Linus of Liege, and was described by an acquaintance of Line's in 1634. Kircher's patron Peiresc had claimed that the clock's motion supported the Copernican cosmological model, the argument being that the magnetic sphere in the clock was caused to rotate by the magnetic force of the sun. Kircher's model disproved the theory, showing that the motion could be produced by a water clock in the base of the device.

Other machines designed by Kircher include an aeolian harp, automatons such as a statue which spoke and listened via a speaking tube, a perpetual motion machine, or a cat piano which would drive spikes into the tails of cats which yowled to specified pitches, although he is not known to have actually constructed the instrument.

The Musurgia Universalis (1650) sets out Kircher's views on music: he believed that the harmony of music reflected the proportions of the universe. The book includes plans for constructing water-powered automatic organs, notations of birdsong and diagrams of musical instruments. One illustration shows the differences between the ears of humans and other animals. In Phonurgia Nova (1673) Kircher considered the possibilities of transmitting music to remote places.

Kircher wrote against the Copernican model in his Magnes (supporting instead that of Tycho Brahe), but in his later Itinerarium extaticum (1656, revised 1671) he presented several systems, including the Copernican, as alternative possibilities. In Polygraphia nova (1663) he proposed an artificial universal language.

Kircher received a copy of the Voynich Manuscript in 1666; it was sent to him by Johannes Marcus Marci in the hope of his being able to decipher it. The manuscript remained in the Collegio Romano until Victor Emmanuel II of Italy annexed the papal states in 1870.

In 1675, he published Arca Noë, the results of his research on the biblical Ark of Noah— following the Counter-Reformation, allegorical interpretation was giving way to the study of the Old Testament as literal truth among Scriptural scholars. Kircher analyzed the dimensions of the Ark; based on the number of species known to him (excluding insects and other forms thought to arise spontaneously), he calculated that overcrowding would not have been a problem. He also discussed the logistics of the Ark voyage, speculating on whether extra livestock was brought to feed carnivores and what the daily schedule of feeding and caring for animals must have been.

[edit] Influence

For most of his professional life, Kircher was one of the scientific stars of the world: according to historian Paula Findlen, he was "the first scholar with a global reputation". His importance was twofold: to the results of his own experiments and research he added information gleaned from his correspondence with over 760 scientists, physicians and above all his fellow Jesuits in all parts of the globe. The Encyclopædia Britannica calls him a "one-man intellectual clearing house". His works, illustrated to his orders, were extremely popular, and he was the first scientist to be able to support himself through the sale of his books. Towards the end of his life his stock fell, as the rationalist Cartesian approach began to dominate (Descartes himself described Kircher as "more quacksalver than savant").

[edit] In culture

Thereafter, Kircher was largely neglected until the late 20th century. One writer attributes his rediscovery to the similarities between his eclectic approach and postmodernism: "at the start of the 21st century Kircher's taste for trivia, deception and wonder is back”; "Kircher's postmodern qualities include his subversiveness, his celebrity, his technomania and his bizarre eclecticism".[5]

In his book For Lust of Knowing, Robert Irwin calls Kircher "one of the last scholars aspiring to know everything", adding that the philosopher Leibniz was probably the last.

As few of Kircher's works have been translated, the contemporary emphasis has been on their aesthetic qualities rather than their actual content, and a succession of exhibitions have highlighted the beauty of their illustrations. Historian Anthony Grafton has said that "the staggeringly strange dark continent of Kircher's work [is] the setting for a Borges story that was never written", while Umberto Eco has written about Kircher in his novel The Island of the Day Before, as well as in his non-fiction works The Search for the Perfect Language and Serendipities. The contemporary artist Cybèle Varela has paid tribute to Kircher in her exhibition Ad Sidera per Athanasius Kircher, held in the Collegio Romano, in the same place where the Museum Kircherianum was.

The Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles has a hall dedicated to the life of Kircher.

Ring of Fire, a series of alternate history novels, employs Fr. Kircher in a variety of short stories and as a backdrop character for the exposition of religious strife during the Thirty Years' War in the novels 1634: The Galileo Affair and 1634: The Bavarian Crisis. In the former his role is relatively minor, as he steps in as curate of Saint Mary's Parish for the parish priest — the newly named last resort Ambassador of the embattled and newly organized United States of Europe (USE) to the Most Serene Republic of Venice — Fr. Lawrence Mazarre. He plays a larger role in 1634: The Bavarian Crisis in which he forms part of a Jesuit information network that helps resolve the personal and political concerns of the staunchly Catholic heroine, Archduchess Maria Anna of Austria and the aid she receives in her flight from citizens and government functionaries of the State of Thuringia-Franconia.

The Athanasius Kircher Society had a weblog devoted to unusual ephemera, which very occasionally relate to Kircher.[6]

[edit] Bibliography

Kircher's principal works, in chronological order, are:

- 1631 Ars Magnesia

- 1635 Primitiae gnomoniciae catroptricae

- 1636 Prodromus coptus sive aegyptiacus

- 1637 Specula Melitensis encyclica, hoc est syntagma novum instrumentorum physico- mathematicorum

- 1641 Magnes sive de arte magnetica

- 1643 Lingua aegyptiaca restituta

- 1645–1646 Ars Magna Lucis et umbrae in mundo

- 1650 Obeliscus Pamphilius

- 1650 Musurgia universalis, sive ars magna consoni et dissoni

- 1652–1655 Oedipus Aegyptiacus

- 1654 Magnes sive (third, expanded edition)

- 1656 Itinerarium extaticum s. opificium coeleste

- 1657 Iter extaticum secundum, mundi subterranei prodromus

- 1658 Scrutinium Physico-Medicum Contagiosae Luis, quae dicitur Pestis

- 1660 Pantometrum Kircherianum ... explicatum a G. Schotto

- 1661 Diatribe de prodigiosis crucibus

- 1663 Polygraphia, seu artificium linguarium quo cum omnibus mundi populis poterit quis respondere

- 1664–1678 Mundus subterraneus, quo universae denique naturae divitiae

- 1665 Historia Eustachio-Mariana

- 1665 Arithmologia

- 1666 Obelisci Aegyptiaci ... interpretatio hieroglyphica

- 1667 China Monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis

- 1667 Magneticum naturae regnum sive disceptatio physiologica

- 1668 Organum mathematicum

- 1669 Principis Cristiani archetypon politicum

- 1669 Latium

- 1669 Ars magna sciendi sive combinatorica

- 1673 Phonurgia nova, sive conjugium mechanico-physicum artis & natvrae paranympha phonosophia concinnatum

- 1675 Arca Noe

- 1676 Sphinx mystagoga

- 1676 Obelisci Aegyptiaci

- 1679 Musaeum Collegii Romani Societatis Jesu

- 1679 Turris Babel, Sive Archontologia Qua Primo Priscorum post diluvium hominum vita, mores rerumque gestarum magnitudo, Secundo Turris fabrica civitatumque exstructio, confusio linguarum, & inde gentium transmigrationis, cum principalium inde enatorum idiomatum historia, multiplici eruditione describuntur & explicantur. Amsterdam, Jansson-Waesberge 1679.

- 1679 Tariffa Kircheriana sive mensa Pathagorica expansa

- 1680 Physiologia Kicheriana experimentalis

[edit] Cited references

- ^ a b Woods, Thomas. How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization, p 4 & 109. (Washington, DC: Regenery, 2005); ISBN 0-89526-038-7.

- ^ "Kircher, Athanasius." Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2007 Ultimate Reference Suite. (2008).

- ^ Palmer, Douglas (2005) Earth Time: Exploring the Deep Past from Victorian England to the Grand Canyon. Wiley, Chichester. ISBN 9780470022214

- ^ Musser, Charles (1990). The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907. University of California Press. pp. 613. ISBN 0-520-08533-7.

- ^ http://www.safran-arts.com/42day/history/h4may/02kirxer.html

- ^ Athanasius Kircher Society Charter[dead link]

[edit] Other sources

- Athanasius Kircher, Dude of Wonders Retrieved Mar. 9, 2009.

- Athanasius Kircher Image Gallery Retrieved Mar. 9, 2009.

- Athanasius Kircher's Magnetic Clock Internet Archive.

- Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (German language) Retrieved Mar. 9, 2009.

- Catholic Encyclopedia Retrieved Oct. 16, 2004.

- Glasgow University Library: Musurgia Universalis Retrieved Oct. 16, 2004.

- Infoplease: Athanasius Kircher Retrieved Oct. 16, 2004.

- The Correspondence of Athanasius Kircher Internet Archive

- The First Use of the Microscope in Medicine Retrieved Oct. 16, 2004.

- The Galileo Project Retrieved Oct. 16, 2004.

- Owners of the Voynich Manuscript Retrieved Feb. 3, 2005.

- The World is Bound With Secret Knots Retrieved Oct. 16, 2004.

- Voynich MS - Biographies Retrieved Oct. 16, 2004.

[edit] Literature

- John Edward Fletcher: A brief survey of the unpublished correspondence of Athanasius Kircher S J. (1602–80), in: Manuscripta, XIII, St. Louis, 1969, pp. 150-60.

- John Edward Fletcher: Johann Marcus Marci writes to Athanasius Kircher. Janus, Leyden, LIX (1972), pp. 97–118

- John Edward Fletcher: Athanasius Kircher und seine Beziehungen zum gelehrten Europa seiner Zeit Wolfenbütteler Arbeiten zur Barockforschung, Band 17, 1988. -

- John Edward Fletcher: "Johann Marcus Marci writes to Athanasius Kircher", Janus, 59 (1972), pp 95–118.

- John Edward Fletcher: Athanasius Kircher : A Man Under Pressure. 1988

- John Edward Fletcher: Athanasius Kircher And Duke August Of Brunswick-Lüneberg : A Chronicle Of Friendship. 1988

- John Edward Fletcher: Athanasius Kircher And His Correspondence. 1988

- Schmidt, Edward W. :The Last Renaissance Man: Athanasius Kircher, SJ. Company: The World of Jesuits and Their Friends. 19(2), Winter 2001–2002.

- Umberto Eco: Serendipities: Language and Lunacy. Columbia University Press (1998). ISBN 0-231-11134-7.

- Paula Findlen: Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything. New York, Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-415-94016-8

- Jean-Pierre Thiollet, Je m'appelle Byblos, Paris, H & D, 2005 (p. 254). ISBN 2-914 266 04 9

- Cybèle Varela: Ad Sidera per Athanasius Kircher. Rome, Gangemi, 2008. ISBN 978-88492-1416-1

- Zielinski, Siegfried. Deep Time of the Media. The MIT Press (April 30, 2008) ISBN-10: 026274032X. ISBN-13: 978-0262740326. p113-157.

[edit] Texts by Athanasius Kircher

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Athanasius Kircher |

- Magnes Siue De Arte Magnetica Opvs Tripartitvm 1643 [2nd ed.]

- Historia Evstachio-Mariana.. 1665.

- Arithmologia sive De abditis numerorum mysterijs 1665.

- Ars Magna Sciendi 1669.

- Latium. Id Est, Nova & Parallela Latii tum Veteris tum Novi Descriptio 1671.

- Obeliscus Pamphilius : hoc est, Interpretatio noua & Hucusque Intentata Obelisci Hieroglyphici 1650.

- Physiologia Kircheriana Experimentalis 1680.

- Sphinx Mystagoga : sive Diatribe hieroglyphica, qua Mumiae, ex Memphiticis Pyramidum Adytis Erutae.. 1676.

- Musurgia Universalis: Volume One; Volume Two 1650.

[edit] External links

- Fairfield University: Athanasius Kircher

- An extensive subcategorized link directory about A. Kircher

- Geology and A. Kircher (PDF files, in German)

- The Museum of Jurassic Technology in Culver City, California includes models of Kircher's inventions.

- University of Lucerne, Switzerland: Kircher-research project (in German)

- Kircherianum Virtuale: A link directory about Kircher and related subjects

- Athanasius Kircher: Contains a short biography, an English translation of Kirchers most wellknown work about the Magic Lantern and of a letter from Kircher to a Swedish prince

- Works by or about Athanasius Kircher in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Kircher, Athanasius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Jesuit scholar |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 2, 1601/1602 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Geisa, Abbacy of Fulda |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 27/November 28, 1680 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Rome |