Steppenwolf (novel)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Steppenwolf | |

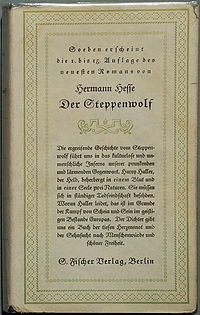

Cover of the original German edition |

|

| Author | Hermann Hesse |

|---|---|

| Original title | Der Steppenwolf |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Language | German |

| Genre(s) | Autobiographical, Novel, Existential |

| Publisher | G. Fischer Verlag (Ger) |

| Publication date | 1927 |

| Media type | print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 237 |

| ISBN | NA |

Steppenwolf (orig. German Der Steppenwolf) is the tenth novel by German-Swiss author Hermann Hesse. Originally published in Germany in 1927, it was first translated into English in 1929. Combining autobiographical and fantastic elements, the novel was named after the lonesome wolf of the steppes. The story in large part reflects a profound crisis in Hesse's spiritual world in the 1920s while memorably portraying the protagonist's split between his humanity, and his wolf-like aggression and homelessness.[1] The novel became an international success, although Hesse would later claim that the book was largely misunderstood.

Contents |

[edit] Background and publication history

In 1924 Hermann Hesse remarried wedding singer Ruth Wenger. After several weeks however, he left Basel, only returning near the end of the year. Upon his return he rented a separate apartment, adding to his isolation. After a short trip to Germany with Wenger, Hesse stopped seeing her almost completely. The resulting feeling of isolation and inability to make lasting contact with the outside world, led to increasing despair and thoughts of suicide. Hesse began writing Steppenwolf in Basel, and finished it in Zürich.[citation needed]In 1926, a precursor to the book, a collection of poems titled The Crisis. From Hermann Hesse's Diary was published. The novel was later released in 1927. The first English edition was published in 1929 by Martin Secker in the United Kingdom and by Henry Holt and Company in the United States. It was translated by Basil Creighton.

[edit] Plot summary

The book is presented as a manuscript by its protagonist, a middle-aged man named Harry Haller, who leaves it to a chance acquaintance, the nephew of his landlady. The acquaintance adds a short preface of his own and then has the manuscript published. The title of this "real" book-in-the-book is Harry Haller's Records (For Madmen Only).

As it begins, the hero is beset with reflections on his being ill-suited for the world of everybody; regular people and his unhappiness in the frivolity of the bourgeois society. In his aimless wanderings about the city he encounters a person carrying an advertisement for a magic theater who gives him a small book, Treatise on the Steppenwolf. This treatise, cited in full in the novel's text as Harry reads it, addresses Harry by name and strikes him as describing himself uncannily. It is a discourse of a man who believes himself to be of two natures: one high, the spiritual nature of man; while the other is low, animalistic; a "wolf of the steppes". This man is entangled in an irresolvable struggle, never content with either nature because he cannot see beyond this self-made concept. The pamphlet gives an explanation of the multifaceted and indefinable nature of every man's soul, which Harry is either unable or unwilling to recognize. It also discusses his suicidal intentions, describing him as one of the "suicides"; people who, deep down knew, they would take their own life one day. But to counter this it hails his potential to be great, to be one of the "Immortals".

The next day Harry meets a former academic friend with whom he had often discussed Indian mythology, and who invites Harry to his home. While there Harry both becomes disgusted by the nationalistic mentality of his friend, who inadvertently criticizes a column written by him himself, and offends the man and his wife by criticizing his wife's picture of Goethe, which he feels is too thickly sentimental and insulting to Goethe's true brilliance, thus cementing his belief that he does not fit in with regular society. Trying to postpone returning home, (where he has plans to commit suicide), Harry walks aimlessly around the town for most of the night, finally stopping to rest at a dance hall where he happens on a young woman, Hermine, who quickly recognizes his desperation. They talk at length, with Hermine alternately mocking his self-pity and indulging him in his view of life, all to his astonished relief. By promising another meeting, Hermine provides Harry with a reason to learn to live, and he eagerly embraces her instruction. Over the next few weeks Hermine introduces Harry to the indulgences of what he calls the "bourgeois": she teaches Harry to dance, introduces him to the casual use of drugs, finds him a lover (Maria), and more importantly, forces him to accept these as legitimate and worthy aspects of a full life.

[edit] The Magic Theater

She also introduces Harry to a mysterious saxophonist named Pablo, who appears to be the very opposite of what Harry considers a serious, thoughtful man. After attending a lavish masquerade ball, Pablo leads Harry to his metaphorical "magic theater", where his previous concerns and higher notions about his soul disintegrate as he participates in several ethereal and phantasmal episodes. The Magic Theater is a place where he can live out possibilities and fantasies of his mind and life. It is described as a long horseshoe shaped corridor, with a vast wall to wall mirror on one side, and countless doors on the other. He enters five of these labeled doors, each symbolic to his life in their own way.

[edit] Major characters

- Harry Haller – the protagonist, a middle-aged man

- Pablo – a saxophonist

- Hermine – a young woman Haller meets at a dance

- Maria – Hermine's friend

[edit] Critical analysis

In the preface to the novel's 1960 edition, Hesse wrote that Steppenwolf was "more often and more violently misunderstood" than any of his other books. Hesse felt that his readers focused only on the suffering and despair that are depicted in Harry Haller's life, thereby missing the possibility of transcendence and healing.[2] This could be due to the fact that at that time Western readers were not familiar with Buddhist philosophy, and therefore missed the point when reading it, because the notion of a human being consisting of a myriad of fragments of different souls is in complete contradiction of Judeo-Christian theologies. Also in the novel, Pablo instructs Harry Haller to relinquish his personality at one point, or at least for the duration of his journey through the corridors of the Magic Theater. In order to do so Harry must learn to use laughter to overcome the tight grip of his personality, to literally laugh at his personality until it shatters into so many small pieces. This concept also ran counter to the egocentric Western culture.

Hesse is a master at blurring the distinction between reality and fantasy. In the moment of climax, it's debatable whether Haller actually kills Hermine or whether the "murder" is just another hallucination in the Magic Theater. It is argued that Hesse does not define reality based on what occurs in physical time and space; rather, reality is merely a function of metaphysical cause and effect.[citation needed] What matters is not whether the murder actually occurred, but rather that at that moment it was Haller's intention to kill Hermine. In that sense, Haller's various states of mind are of more significance than his actions.

It is also notable that the very existence of Hermine in the novel is never confirmed; the manuscript left in Harry Haller's room reflects a story that completely revolves around his personal experiences. In fact when Harry asks Hermine what her name is, she turns the question around. When he is challenged to guess her name, he tells her that she reminds him of a childhood friend named Hermann, and therefore he concludes, her name must be Hermine. Metaphorically, Harry creates Hermine as if a fragment of his own soul has broken off to form a female counterpart.

The underlying theme of transcendence is shown within group interaction and dynamics. Throughout the novel Harry concerns himself with being different, with separating himself from those he is around. Harry believes that he is better than his surroundings and fails to understand why he cannot be recognized as such, which raises the idea that in order to rise above a group one must first become one with a part of it.

The duality of human nature is the major theme in the novel[citation needed] and its two main characters, Harry Haller and Hermine, illustrate this duality. Harry illustrates the duality through an inner conflict and an outer conflict. Inwardly, he believes two opposing natures battle over possession of him, a man and a wolf, high and low, spirit and animal. While he actually longs to live as a wolf free of social convention, he lives as a bourgeois bachelor, but his opposing wolfish nature isolates him from others until he meets Hermine.

Hermine represents the duality of human nature through an outer conflict. Hermine is a socialite, a foil to the isolated bachelor, and she coerces Harry to agree to subject himself to society, learning from her, in exchange for her murder. As Harry struggles through social interaction his isolation diminishes and he and Hermine grow closer to one another as the moment of her death approaches. The climax of the dualistic struggle culminates in the Magic Theater where Harry, seeing himself as a wolf, murders Hermine the socialite.

[edit] Critical reception

Hermann Hesse considered Steppenwolf to be the most misunderstood of his novels. American novelist Jack Kerouac dismissed it in On the Road (1951) and it has had a long history of mixed critical reception and opinion at large. From the very beginning, reception was harsh. Already upset with Hesse's novel Siddhartha, political activists and patriots railed against him, and against the book, seeing an opportunity to discredit Hesse. Even close friends and longtime readers criticized the novel for its perceived lack of morality in its open depiction of sex and drug use, a criticism that indeed remained the primary rebuff of the novel for many years.[3] However as society changed and formerly taboo topics such as sex and drugs became more openly discussed, critics came to attack the book for other reasons; mainly that it was too pessimistic, and that it was a journey in the footsteps of a psychotic and showed humanity through his warped and unstable viewpoint, a fact that Hesse did not dispute, although he did respond to critics by noting the novel ends on a theme of new hope.

Popular interest in the novel was renewed in the 1960s, primarily because it was seen as a counterculture book and because of its depiction of free love and frank drug usage. It was also introduced in many new colleges for study and interest in the book and in Herman Hesse was feted in America for more than a decade afterwards.

[edit] "Treatise on the Steppenwolf"

The "Treatise on the Steppenwolf" is a booklet given to Harry Haller which describes himself. It is a literary mirror and, from the outset, describes what Harry had not learned, namely "to find contentment in himself and his own life." The cause of his discontent was the perceived dualistic nature of a human and a wolf within Harry. The treatise describes, as earmarks of his life, a threefold manifestation of his discontent: one, isolation from others, two, suicidal tendencies, and three, relation to the bourgeois. Harry isolates himself from others socially and professionally, frequently resists the temptation to take his life, and experiences feelings of benevolence and malevolence for bourgeois notions. The booklet predicts Harry may come to terms with his state in the dawning light of humor.

[edit] References in popular culture

Hesse's 1928 short story "Harry, the Steppenwolf" forms a companion piece to the novel. It is about a wolf named Harry who is kept in a zoo, and who entertains crowds by destroying images of German cultural icons like Goethe and Mozart.

The name Steppenwolf has become notable in popular culture for various organizations and establishments. In 1967, the band Steppenwolf, headed by German-born singer John Kay, took their name from the novel. The Belgian band DAAU (die Anarchistische Abendunterhaltung) is named after one of the advertising slogans of the novel's magical theatre. The Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago, which was founded in 1974 by actor Gary Sinese, also took its name from the novel. The track "Steppenwolf" on English rock band Hawkwind's album Astounding Sounds, Amazing Music is directly inspired by the novel and includes references to the magic theatre and the dual nature of the wolfman-manwolf.

[edit] Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

The novel was adapted into a film of the same name in 1974. Starring Max Von Sydow and Dominique Sanda, it was directed by Fred Haines.

[edit] Footnotes

[edit] References

- Cornils, Ingo and Osman Durrani. 2005. Hermann Hesse Today. University of London Institute of Germanic Studies. ISBN 904201606X

- Freedman, Ralph. 1978. "Hermann Hesse: Pilgrim of Crisis a Biography". Pantheon Books

- Halkin, Ariela. 1995. The Enemy Reviewed: German Popular Literature Through British Eyes Between the Two World Wars. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0275951014

- Mileck, Joseph. 1981. Hermann Hesse: Life and Art. University of California Press. ISBN 0520041526

- Poplawski, Paul. 2003. Encyclopedia of Literary Modernism. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313016578

- Ziolkowski, Theodore. 1969. Foreword of The Glass Bead Game. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-1246-X

[edit] External links

- Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse

- Steppenwolf the Genius of Suffering by Hassan M. Malik

- Steppenwolf at the Internet Movie Database