Lafcadio Hearn

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

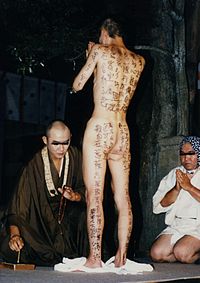

Patrick Lafcadio Hearn (27 June 1850 - 26 September 1904), also known as Koizumi Yakumo (小泉八雲 ) after gaining Japanese citizenship, was an author, best known for his books about Japan. He is especially well-known for his collections of Japanese legends and ghost stories, such as Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things.

Contents |

[edit] Biography

[edit] Early life

Hearn was born in Lefkada (the origin of his middle name), one of the Greek Ionian Islands. He was the son of Surgeon-major Charles Hearn (of County Offaly, Ireland) and Rosa Antonia Kassimati ,[1] who had been born on Kythera, an island in the Myrtoon Pelagos (currently in the municipality of Athens). His father was stationed in Lefkada during the British occupation of the islands. Lafcadio was initially baptized Patricio Lefcadio Tessima Carlos Hearn in the Greek Orthodox Church. It is not clear that Hearn's parents were ever legally married, and the Irish Protestant relatives on his father's side considered him to have been born out of wedlock. (This may, however, have been because they did not recognize the legitimacy of the Greek Orthodox Church to conduct a marriage ceremony for a Protestant.)[2]

Hearn moved to Dublin, Ireland, at the age of two, where he was brought up in the suburb of Rathmines. Artistic and rather bohemian tastes were in his blood. His father's brother Richard was at one time a well-known member of the Barbizon set of artists, though he made no mark as a painter due to his lack of energy. Young Hearn had a rather casual education, but in 1865 was at Ushaw Roman Catholic College, Durham. He was injured in a playground accident in his teens, causing loss of vision in his left eye.

[edit] Emigration

The religious faith in which he was brought up was, however, soon lost, and at 19 he was sent to live in the United States of America, where he settled in Cincinnati, Ohio. For a time, he lived in utter poverty, which may have contributed to his later paranoia and distrust of those around him[citation needed]. He eventually found a friend in the English printer and communalist Henry Watkin. With Watkin's help, Hearn picked up a living in the lower grades of newspaper work.

Through the strength of his talent as a writer, Hearn quickly advanced through the newspaper ranks and became a reporter for the Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, working for the paper from 1872 to 1875. With creative freedom in one of Cincinnati's largest circulating newspapers, he developed a reputation as the paper's premier sensational journalist, as well as the author of sensitive, dark, and fascinating accounts of Cincinnati's disadvantaged. He continued to occupy himself with journalism and with out-of-the-way observation and reading, and meanwhile his erratic, romantic, and rather morbid idiosyncrasies developed.

While in Cincinnati, he married Alethea ("Mattie") Foley, a black woman, an illegal act at the time. When the scandal was discovered and publicized, he was fired from the Enquirer and went to work for the rival Cincinnati Commercial.

In 1874 Hearn and the young Henry Farny, later a renowned painter of the American West, wrote, illustrated, and published a weekly journal of art, literature, and satire they titled Ye Giglampz that ran for nine issues. The Cincinnati Public Library reprinted a facsimile of all nine issues in 1983.

[edit] New Orleans

In the autumn of 1877, Hearn left Cincinnati for New Orleans, Louisiana, where he initially wrote dispatches on his discoveries in the "Gateway to the Tropics" for the Cincinnati Commercial. He lived in New Orleans for nearly a decade, writing first for the Daily City Item and later for the Times Democrat. The vast number of his writings about New Orleans and its environs, many of which have not been collected, include the city's Creole population and distinctive cuisine, the French Opera, and Vodou. His writings for national publications, such as Harper's Weekly and Scribner's Magazine, helped mold the popular image of New Orleans as a colorful place with a distinct culture more akin to Europe and the Caribbean than to the rest of North America. His best-known Louisiana works are Gombo Zhèbes, Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs in Six Dialects (1885); La Cuisine Créole (1885), a collection of culinary recipes from leading chefs and noted Creole housewives who helped make New Orleans famous for its cuisine; and Chita: A Memory of Last Island, a novella based on the hurricane of 1856 first published in Harper's Monthly in 1888. Little known then, even today he is relatively unknown outside the circle of New Orleans cultural devotees. However, more books have been written about him than any former resident of New Orleans other than Louis Armstrong. His footprint in the history of Creole cooking is visible even today.[3]

Hearn's writings for the New Orleans newspapers included impressionistic sketches of New Orleans places and characters and many stern, vigorous editorials denouncing political corruption, street crime, violence, intolerance and the failures of public health and hygiene officials. Despite the fact that Hearn is credited with "inventing" New Orleans as an exotic and mysterious place, his obituaries on the vodou leaders Marie Laveau and "Doctor" John Montenet are matter-of-fact and debunking. Dozens of Hearn's New Orleans writings are collected in Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn, a book edited by S. Fredrick Starr and published in 2001 by the University Press of Mississippi. (Professor Starr's scholarly introduction to Inventing New Orleans notes than many Japanese scholars of Hearn's life and work are now studying his decade in New Orleans.)[4]

Harper's sent Hearn to the West Indies as a correspondent in 1887. He spent two years in Martinique and produced two books: Two Years in the French West Indies and Youma, The Story of a West-Indian Slave, both in 1890.

[edit] Later life in Japan

In 1890, Hearn went to Japan with a commission as a newspaper correspondent, which was quickly broken off. It was in Japan, however, that he found his home and his greatest inspiration. Through the goodwill of Basil Hall Chamberlain, Hearn gained a teaching position in the summer of 1890 at the Shimane Prefectural Common Middle School and Normal School in Matsue, a town in western Japan on the coast of the Sea of Japan. Most Japanese identify Hearn with Matsue, as it was here that his image of Japan was molded. Today, the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum and his old residence are still two of Matsue's most popular tourist attractions. During his 15-month stay in Matsue, Hearn married Setsu Koizumi, the daughter of a local samurai family, and became a naturalized Japanese, taking the name Koizumi Yakumo.

In late 1891, Hearn took another teaching position in Kumamoto, Kyushu, at the Fifth Higher Middle School, where he spent the next three years and completed his book Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894). In October 1894 he secured a journalism position with the English-language Kobe Chronicle, and in 1896, with some assistance from Chamberlain, he began teaching English literature at Tokyo (Imperial) University, a post he held until 1903. In 1904, he was a professor at Waseda University. On September 26, 1904, he died of heart failure at the age of 54.

In the late 19th century Japan was still largely unknown and exotic to the Western world. With the introduction of Japanese aesthetics, however, particularly at the Paris World's Fair of 1900, the West had an insatiable appetite for exotic Japan, and Hearn became known to the world through the depth, originality, sincerity, and charm of his writings. In later years, some critics would accuse Hearn of exoticizing Japan, but as the man who offered the West some of its first glimpses into pre-industrial and Meiji Era Japan, his work still offers valuable insight today.

[edit] Legacy

The Japanese director Masaki Kobayashi adapted four Hearn tales into his 1965 film, Kwaidan. Some of his stories have been adapted by Ping Chong into his trademark puppet theatre, including the 1999 Kwaidan and the 2002 OBON: Tales of Moonlight and Rain.

Hearn's life and works were celebrated in The Dream of a Summer Day, a play that toured Ireland in April and May 2005, which was staged by the Storytellers Theatre Company and directed by Liam Halligan. It is a detailed dramatization of Hearn's life, with four of his ghost stories woven in.

Yone Noguchi is quoted as saying about Hearn, "His Greek temperament and French culture became frost-bitten as a flower in the North."[5]

There is also a cultural center named for Hearn at the University of Durham.

Hearn was a major translator of the short stories of Guy de Maupassant.[6]

In Ian Fleming's You only Live Twice, James Bond retorts to his nemesis Blofeld's comment of "Have you ever heard the Japanese expression kirisute gomen?" with "Spare me the Lafcadio Hearn, Blofeld."

[edit] Books written by Hearn on Japanese subjects

- Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894)

- Out of the East: Reveries and Studies in New Japan (1895)

- Kokoro: Hints and Echoes of Japanese Inner Life (1896)

- Gleanings in Buddha-Fields: Studies of Hand and Soul in the Far East (1897)

- Exotics and Retrospectives (1898)

- Japanese Fairy Tales (1898) and sequels

- In Ghostly Japan (1899)

- Shadowings (1900)

- Japanese Lyrics (1900) - on haiku

- A Japanese Miscellany (1901)

- Kottō: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs (1902)

- Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1903) (which was later made into the movie Kwaidan by Masaki Kobayashi)

- Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation (1904; published just after his death)[7]

- The Romance of the Milky Way and other studies and stories (1905; published posthumously)

[edit] References

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- ^ Hearn's Parents

- ^ Hearn, Lafcadio; Starr, S. Frederick (2001), Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn, University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 1578063531, http://www.upress.state.ms.us/catalog/spring2001/inventing_new_orleans.html Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn

- ^ A chronicle of Creole cuisine | Chron.com - Houston Chronicle

- ^ Hearn, Lafcadio; Starr, S. Frederick (2001), Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn, University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 1578063531, http://www.upress.state.ms.us/catalog/spring2001/inventing_new_orleans.html Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn

- ^ Yone Noguchi

- ^ Lafcadio Hearn Bibliography

- ^ http://hwpbc.gate01.com/mtoda/mtoda/onhisgreekidentity.html

[edit] Further reading

- Bisland, Elizabeth. (1906). The Life and Letters of Lafcadio Hearn, Vol. I. New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- __________________. (1906). The Life and Letters of Lafcadio Hearn, Vol. II. New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- Bronner, Milton, editor, Letters from the Raven: Being the Correspondence of Lafcadio Hearn with Henry Watkin (1907)

- Cott, Jonathan. Wandering Ghost: The Odyssey of Lafcadio Hearn (1991)

- Gould, G. M. Concerning Lafcadio Hearn (1908)

- Hearn, Lafcadio, Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn,S. Frederick Starr, editor (University Press of Mississippi, 2001)

- Hearn, Lafcadio. Lafcadio Hearn's America, Simon J. Bronner, editor (2002)

- Kennard, Nina H., Lafcadio Hearn; containing some letters from Lafcadio Hearn to his half-sister, Mrs. Atkinson (New York, D. Appleton and company, 1912) [1]

- Lurie, David. "Orientomology: The Insect Literature of Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904)", in JAPANimals: History and Culture in Japan's Animal Life, ed. Gregory M. Pflugfelder and Brett L. Walker, University of Michigan Press, 2005.

- Noguchi, Yone. Lafcadio Hearn in Japan (1910)

- Pulvers, Roger. Lafcadio Hearn: interpreter of two disparate worlds, Japan Times, January 19, 2000

- Starrs, Roy "Lafcadio Hearn as Japanese Nationalist", in "Nichibunken Japan Review: Journal of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies", Number 18, 2006, pp.181-213.

[edit] External links

| This article's external links may not follow Wikipedia's content policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Lafcadio Hearn |

- Works by Lafcadio Hearn at Project Gutenberg

- See more on Hearn here.

- A Lafcadio Hearn Virtual iDiary

- Lafcadio Hearn and Haiku

- K. Inadomi's Private Library

- Exploring Lafcadio Hearn in Japan

- Hearn's influence in literature

- Selections from Hearn's Japanese Fairy Tales

- Lafcadio Hearn's grave

- essay by Roy Starrs on "Lafcadio Hearn as a Japanese Nationalist"

- Lafcadio Hearn street - A Greek site about Hearn