Statistical hypothesis testing

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A statistical hypothesis test is a method of making statistical decisions using experimental data. It is sometimes called confirmatory data analysis, in contrast to exploratory data analysis. In frequency probability, these decisions are almost always made using null-hypothesis tests; that is, ones that answer the question Assuming that the null hypothesis is true, what is the probability of observing a value for the test statistic that is at least as extreme as the value that was actually observed?[1] One use of hypothesis testing is deciding whether experimental results contain enough information to cast doubt on conventional wisdom.

It is a key technique of frequentist statistical inference, and is widely used,[citation needed] but also much criticized. The main alternative is Bayesian inference.

The critical region of a hypothesis test is the set of all outcomes which, if they occur, cause the null hypothesis to be rejected and the alternative hypothesis accepted. It is usually denoted by C.

Contents |

[edit] Example

As an example, consider determining whether a suitcase contains some radioactive material. Placed under a Geiger counter, it produces 10 counts per minute. The null hypothesis is that no radioactive material is in the suitcase and that all measured counts are due to ambient radioactivity typical of the surrounding air and harmless objects. We can then calculate how likely it is that the null hypothesis produces 10 counts per minute. If the null hypothesis predicts (say) on average 9 counts per minute and a standard deviation of 1 count per minute, then we say that the suitcase is compatible with the null hypothesis. (This does not guarantee that there is no radioactive material, just that we have no reason to believe it); on the other hand, if the null hypothesis predicts 3 counts per minute and a standard deviation of 1 count per minute, then the suitcase is not compatible with the null hypothesis, and there are likely other factors responsible to produce the measurements.

The test described here is more fully the null-hypothesis statistical significance test. The null hypothesis is a conjecture made solely to be falsified by the sample. Statistical significance is a possible finding of the test – that the sample is unlikely to have occurred by chance given the truth of the null hypothesis. The name of the test describes its formulation and its possible outcome. One characteristic of the test is its crisp decision: reject or do not reject (which is not the same as accept). A calculated value is compared to a threshold, which is determined from the tolerable risk of error.

[edit] Definition of terms

The following definitions are mainly based on the exposition in Lehmann and Romano[2]:

- Simple hypothesis

- Any hypothesis which specifies the population distribution completely.

- Composite hypothesis

- Any hypothesis which does not specify the population distribution completely.

- Statistical test

- A decision function that takes its values in the set of hypotheses.

- Region of acceptance

- The set of values for which we fail to reject the null hypothesis.

- Region of rejection / Critical region

- The set of values of the test statistic for which the null hypothesis is rejected.

- Power of a test (1 − β)

- The test's probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis. The complement of the false negative rate, β.

- Size / Significance level of a test (α)

- For simple hypotheses, this is the test's probability of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis. The false positive rate. For composite hypotheses this is the upper bound of the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis over all cases covered by the null hypothesis.

- Most powerful test

- For a given size or significance level, the test with the greatest power.

- Uniformly most powerful test (UMP)

- A test with the greatest power for all values of the parameter being tested.

- Consistent test

- When considering the properties of a test as the sample size grows, a test is said to be consistent if, for a fixed size of test, the power against any fixed alternative approaches 1 in the limit.[3]

- Unbiased test

- For a specific alternative hypothesis, a test is said to be unbiased when the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis is not less than the significance level when the alternative is true and is less than or equal to the significance level when the null hypothesis is true.

- Uniformly most powerful unbiased (UMPU)

- A test which is UMP in the set of all unbiased tests.

[edit] Common test statistics

See legend defining symbols at bottom of table. The statistics for some other tests have their own articles, including the Wald test and the likelihood ratio test.

| Name | Formula | Assumptions |

| One-sample z-test |  |

(Normal distribution or n > 30) and σ known. (z is the distance from the mean in relation to the standard deviation of the mean). For non-normal distributions it is possible to calculate a minimum proportion of a population that falls within k standard deviations for any k (see: Chebyshev's inequality). |

| Two-sample z-test |  |

Normal distribution and independent observations and both (σ1 and σ2 known) |

| One-sample t-test |

|

(Normal population or n > 30) and σ unknown |

| Paired t-test |

|

(Normal population of differences or n > 30) and σ unknown |

| One-proportion z-test |  |

n .p > 10 and n (1 − p) > 10 and it is a SRS (Simple Random Sample). |

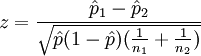

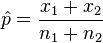

| Two-proportion z-test, equal variances |

|

n1 p1 > 5 and n1(1 − p1) > 5 and n2 p2 > 5 and n2(1 − p2) > 5 and independent observations |

| Two-proportion z-test, unequal variances |  |

n1 p1 > 5 and n1(1 − p1) > 5 and n2 p2 > 5 and n2(1 − p2) > 5 and independent observations |

| Name | Formula | Assumptions |

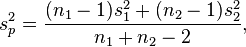

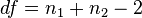

| Two-sample pooled t-test |

|

(Normal populations or n1 + n2 > 40) and independent observations and σ1 = σ2 and (σ1 and σ2 unknown) |

| Two-sample unpooled t-test |

|

(Normal populations or n1 + n2 > 40) and independent observations and σ1 ≠ σ2 and (σ1 and σ2 unknown) |

| Definition of symbols | n = sample size = sample mean = sample meanμ0 = population mean σ = population standard deviation t = t statistic df = degrees of freedom n1 = sample 1 size n2 = sample 2 size s1 = sample 1 std. deviation s2 = sample 2 std. deviation

|

[edit] Origins

Hypothesis testing is largely the product of Ronald Fisher, Jerzy Neyman, Karl Pearson and (son) Egon Pearson. Fisher was an agricultural statistician who emphasized rigorous experimental design and methods to extract a result from few samples assuming Gaussian distributions. Neyman (who teamed with the younger Pearson) emphasized mathematical rigor and methods to obtain more results from many samples and a wider range of distributions. Modern hypothesis testing is an (extended) hybrid of the Fisher vs Neyman/Pearson formulation, methods and terminology developed in the early 20th century.

[edit] Example

The following example is summarized from Fisher[4] Fisher thoroughly explained his method in a proposed experiment to test a Lady's claimed ability to determine the means of tea preparation by taste. The article is less than 10 pages in length and is notable for its simplicity and completeness regarding terminology, calculations and design of the experiment. The example is loosely based on an event in Fisher's life. The Lady proved him wrong.[5]

- The null hypothesis was that the Lady had no such ability.

- The test statistic was a simple count of the number of successes in 8 trials.

- The distribution associated with the null hypothesis was the binomial distribution familiar from coin flipping experiments.

- The critical region was the single case of 8 successes in 8 trials based on a conventional probability criterion (< 5%).

- Fisher asserted that no alternative hypothesis was (ever) required.

If, and only if the 8 trials produced 8 successes was Fisher willing to reject the null hypothesis – effectively acknowledging the Lady's ability with > 98% confidence (but without quantifying her ability). Fisher later discussed the benefits of more trials and repeated tests.

[edit] Criticism

| This article's tone or style may not be appropriate for Wikipedia. Specific concerns may be found on the talk page. See Wikipedia's guide to writing better articles for suggestions. (April 2008) |

| This article's Criticism or Controversy section(s) may mean the article does not present a neutral point of view of the subject. It may be better to integrate the material in such sections into the article as a whole. |

| This article is missing citations or needs footnotes. Please help add inline citations to guard against copyright violations and factual inaccuracies. (January 2008) |

Some statisticians have commented that pure "significance testing" has what is actually a rather strange goal of detecting the existence of a "real" difference between two populations. In practice a difference can almost always be found given a large enough sample, what is typically the more relevant goal of science is a determination of causal effect size. The amount and nature of the difference, in other words, is what should be studied.[6] Many researchers also feel that hypothesis testing is something of a misnomer. In practice a single statistical test in a single study never "proves" anything.[citation needed]

Rejection of the null hypothesis at some effect size has no bearing on the practical significance at the observed effect size. A statistically significant finding may not be relevant in practice due to other, larger effects of more concern, whilst a true effect of practical significance may not appear statistically significant if the test lacks the power to detect it. Appropriate specification of both the hypothesis and the test of said hypothesis is therefore important to provide inference of practical utility.

[edit] Meta-criticism

Little criticism of the technique appears in introductory statistics texts. Criticism is of the application, or of the interpretation, rather than of the method.

Criticism of null-hypothesis significance testing is available in other articles (for example "Statistical significance") and their references. Attacks and defenses of the null-hypothesis significance test are collected in Harlow et al.[7]

The original purposes of Fisher's formulation, as a tool for the experimenter, was to plan the experiment and to easily assess the information content of the small sample. There is little criticism, Bayesian in nature, of the formulation in its original context.

In other contexts, complaints focus on flawed interpretations of the results and over-dependence/emphasis on one test.

Numerous attacks on the formulation have failed to supplant it as a criterion for publication in scholarly journals. The most persistent attacks originated from the field of Psychology. After review, the American Psychological Association did not explicitly deprecate the use of null-hypothesis significance testing, but adopted enhanced publication guidelines which implicitly reduced the relative importance of such testing. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recognizes an obligation to publish negative (not statistically significant) studies under some circumstances. The applicability of the null-hypothesis testing to the publication of observational (as contrasted to experimental) studies is doubtful.

[edit] Philosophical criticism

Philosophical criticism to hypothesis testing includes consideration of borderline cases.

Any process that produces a crisp decision from uncertainty is subject to claims of unfairness near the decision threshold. (Consider close election results.) The premature death of a laboratory rat during testing can impact doctoral theses and academic tenure decisions.

"... surely, God loves the .06 nearly as much as the .05"[8]

The statistical significance required for publication has no mathematical basis, but is based on long tradition.

"It is usual and convenient for experimenters to take 5% as a standard level of significance, in the sense that they are prepared to ignore all results which fail to reach this standard, and, by this means, to eliminate from further discussion the greater part of the fluctuations which chance causes have introduced into their experimental results."[4]

Fisher, in the cited article, designed an experiment to achieve a statistically significant result based on sampling 8 cups of tea.

Ambivalence attacks all forms of decision making. A mathematical decision-making process is attractive because it is objective and transparent. It is repulsive because it allows authority to avoid taking personal responsibility for decisions.

[edit] Pedagogic criticism

Pedagogic criticism of the null-hypothesis testing includes the counter-intuitive formulation, the terminology and confusion about the interpretation of results.

"Despite the stranglehold that hypothesis testing has on experimental psychology, I find it difficult to imagine a less insightful means of transiting from data to conclusions."[9]

Students find it difficult to understand the formulation of statistical null-hypothesis testing. In rhetoric, examples often support an argument, but a mathematical proof "is a logical argument, not an empirical one". A single counterexample results in the rejection of a conjecture. Karl Popper defined science by its vulnerability to dis-proof by data. Null-hypothesis testing shares the mathematical and scientific perspective rather than the more familiar rhetorical one. Students expect hypothesis testing to be a statistical tool for illumination of the research hypothesis by the sample; It is not. The test asks indirectly whether the sample can illuminate the research hypothesis.

Students also find the terminology confusing. While Fisher disagreed with Neyman and Pearson about the theory of testing, their terminologies have been blended. The blend is not seamless or standardized. While this article teaches a pure Fisher formulation, even it mentions Neyman and Pearson terminology (Type II error and the alternative hypothesis). The typical introductory statistics text is less consistent. The Sage Dictionary of Statistics would not agree with the title of this article, which it would call null-hypothesis testing. [1] "...there is no alternate hypothesis in Fisher's scheme: Indeed, he violently opposed its inclusion by Neyman and Pearson."[10] In discussing test results, "significance" often has two distinct meanings in the same sentence; One is a probability, the other is a subject-matter measurement (such as currency). The significance (meaning) of (statistical) significance is significant (important).

There is widespread and fundamental disagreement on the interpretation of test results.

"A little thought reveals a fact widely understood among statisticians: The null hypothesis, taken literally (and that's the only way you can take it in formal hypothesis testing), is almost always false in the real world.... If it is false, even to a tiny degree, it must be the case that a large enough sample will produce a significant result and lead to its rejection. So if the null hypothesis is always false, what's the big deal about rejecting it?"[10] (The above criticism only applies to point hypothesis tests. If one were testing, for example, whether a parameter is greater than zero, it would not apply.)

"How has the virtually barren technique of hypothesis testing come to assume such importance in the process by which we arrive at our conclusions from our data?"[9]

Null-hypothesis testing just answers the question of "how well the findings fit the possibility that chance factors alone might be responsible."[1]

Null-hypothesis significance testing does not determine the truth or falseness of claims. It determines whether confidence in a claim based solely on a sample-based estimate exceeds a threshold. It is a research quality assurance test, widely used as one requirement for publication of experimental research with statistical results. It is uniformly agreed that statistical significance is not the only consideration in assessing the importance of research results. Rejecting the null hypothesis is not a sufficient condition for publication.

"Statistical significance does not necessarily imply practical significance!"[11]

[edit] Practical criticism

Practical criticism of hypothesis testing includes the sobering observation that published test results are often contradicted. Mathematical models support the conjecture that most published medical research test results are flawed. Null-hypothesis testing has not achieved the goal of a low error probability in medical journals. [12][13]

Many authors have expressed a strong skepticism, sometimes labeled as postmodernism, about the general unreliability of statistical hypothesis testing to explain many social and medical phenomena. For example, modern statistics do not reliably link exposures of carcinogens to spatial-temporal patterns of cancer incidence. There is not a strong convention in statistical hypothesis testing to consider alternate units of scale. With temporal data the units chosen for temporal aggregation (hour, day, week, year, decade) can completely alter the trends and cycles. With spatial data, the units chosen for analysis (the modifiable areal unit problem) can alter or reverse relationships between variables. If the issue of analysis scale is ignored in a hypothesis test then skepticism about the results is justified.

[edit] Straw man

Hypothesis testing is controversial when the alternative hypothesis is suspected to be true at the outset of the experiment, making the null hypothesis the reverse of what the experimenter actually believes; it is put forward as a straw man only to allow the data to contradict it. Many statisticians have pointed out that rejecting the null hypothesis says nothing or very little about the likelihood that the null is true. Under traditional null hypothesis testing, the null is rejected when the conditional probability P(Data as or more extreme than observed | Null) is very small, say 0.05. However, some say researchers are really interested in the probability P(Null | Data as actually observed) which cannot be inferred from a p-value: some like to present these as inverses of each other but the events "Data as or more extreme than observed" and "Data as actually observed" are very different. In some cases, P(Null | Data) approaches 1 while P(Data as or more extreme than observed | Null) approaches 0,[citation needed] in other words, we can reject the null when it's virtually certain to be true.[citation needed] For this and other reasons, Gerd Gigerenzer has called null hypothesis testing "mindless statistics" [14] while Jacob Cohen described it as a ritual conducted to convince ourselves that we have the evidence needed to confirm our theories.[15]

[edit] Bayesian criticism

Bayesian statisticians normally reject the idea of null hypothesis testing, instead using various techniques in Bayesian inference. Given a prior probability distribution for one or more parameters, sample evidence can be used to generate an updated posterior distribution. In this framework, but not in the null hypothesis testing framework, it is meaningful to make statements of the general form "the probability that the true value of the parameter is greater than 0 is p". According to Bayes Theorem, we have:

thus P(Null | Data) approaches 1 while P(Data | Null) approaches 0 exactly when P(Null)/P(Data) approaches 1, i.e. (for instance) when the a priori probability of the null hypothesis, P(Null), is also approaching 1, while P(Data) approaches 0: then P(Data | Null) is low because we have extremely unlikely data, but the Null hypothesis is extremely likely to be true.

[edit] Publication bias

In 2002, a group of psychologists launched a new journal dedicated to experimental studies in psychology which support the null hypothesis. The Journal of Articles in Support of the Null Hypothesis (JASNH) was founded to address a scientific publishing bias against such articles. According to the editors,

- "other journals and reviewers have exhibited a bias against articles that did not reject the null hypothesis. We plan to change that by offering an outlet for experiments that do not reach the traditional significance levels (p < 0.05). Thus, reducing the file drawer problem, and reducing the bias in psychological literature. Without such a resource researchers could be wasting their time examining empirical questions that have already been examined. We collect these articles and provide them to the scientific community free of cost."

The "File Drawer problem" is a problem that exists due to the fact that academics tend not to publish results that indicate the null hypothesis could not be rejected. This does not mean that the relationship they were looking for did not exist, but it means they couldn't prove it. Even though these papers can often be interesting, they tend to end up unpublished, in "file drawers."

Ioannidis has inventoried factors that should alert readers to risks of publication bias.[16]

[edit] Improvements

Jones and Tukey suggested a modest improvement in the original null-hypothesis formulation to formalize handling of one-tail tests. Fisher ignored the 8-failure case (equally improbable as the 8-success case) in the example test involving tea, which altered the claimed significance by a factor of 2[17].

Killeen proposed an alternative statistic that estimates the probability of duplicating an experimental result. It "provides all of the information now used in evaluating research, while avoiding many of the pitfalls of traditional statistical inference." [18]

[edit] See also

- Comparing means test decision tree

- Counternull

- Multiple comparisons

- Omnibus test

- Behrens–Fisher problem

- Bootstrapping (statistics)

- Checking if a coin is fair

- Falsifiability

- Fisher's method for combining independent tests of significance

- Null hypothesis

- P-value

- Statistical theory

- Statistical significance

- Type I error, Type II error

- Exact test

[edit] References

- ^ a b c The Sage Dictionary of Statistics, pg. 76, Duncan Cramer, Dennis Howitt, 2004, ISBN 076194138X

- ^ E.L. Lehmann and Joseph P. Romano (2005). Testing Statistical Hypotheses (3E ed.). New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 0387988645.

- ^ D.R. Cox and D.V.Hinkley (1974). Theoretical Statistics. ISBN 0412124293.

- ^ a b Fisher, Sir Ronald A. (1956) [1935]. "Mathematics of a Lady Tasting Tea". in James Roy Newman. The World of Mathematics, volume 3. http://books.google.com/books?id=oKZwtLQTmNAC&pg=PA1512&dq=%22mathematics+of+a+lady+tasting+tea%22&sig=8-NQlCLzrh-oV0wjfwa0EgspSNU..

- ^ R.A. Fisher, the Life of a Scientist, Box, 1978, p134

- ^ Mccloskey, Deirdre (2008). The Cult of Statistical Significance. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472050079.

- ^ What If There Were No Significance Tests?, Harlow, Mulaik & Steiger, 1997, ISBN 978-0-8058-2634-0.

- ^ Rosnow, R.L. & Rosenthal, R. (1989). Statistical procedures and the justification of knowledge in psychological science. American Psychologist, 44, 1276-1284.

- ^ a b Loftus, G.R. 1991. On the tyranny of hypothesis testing in the social sciences. Contemporary Psychology 36: 102-105.

- ^ a b Cohen, J. 1990. Things I have learned (so far). American Psychologist 45: 1304-1312.

- ^ Introductory Statistics, Fifth Edition, 1999, pg. 521, Neil A. Weiss, ISBN 0-201-59877-9

- ^ Ioannidis JP (July 2005). "Contradicted and initially stronger effects in highly cited clinical research". JAMA 294 (2): 218–28. doi:. PMID 16014596.

- ^ Ioannidis JP (August 2005). "Why most published research findings are false". PLoS Med. 2 (8): e124. doi:. PMID 16060722.

- ^ Gigerenzer, Gerd. 'Mindless statistics', The Journal of Socio-Economics, Vol 33, 2004. pp. 587-606.

- ^ Cohen, Jacob (1994) 'The earth is round (p < .05)', American Psychologist, Vol 49(12), Dec 1994. pp. 997–1003.

- ^ Ioannidis J (2005). "Why most published research findings are false". PLoS Med 2 (8): e124. doi:. PMID 16060722.

- ^ Jones LV, Tukey JW (December 2000). "A sensible formulation of the significance test". Psychol Methods 5 (4): 411–4. doi:. PMID 11194204. http://content.apa.org/journals/met/5/4/411.

- ^ Killeen PR (May 2005). "An alternative to null-hypothesis significance tests". Psychol Sci 16 (5): 345–53. doi:. PMID 15869691.

[edit] External links

- A Guide to Understanding Hypothesis Testing

- Hypothesis Testing: The Basics

- A good Introduction

- Bayesian critique of classical hypothesis testing

- Critique of classical hypothesis testing highlighting long-standing qualms of statisticians

- Dallal GE (2007) The Little Handbook of Statistical Practice (A good tutorial)

- References for arguments for and against hypothesis testing

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

= sample mean of differences

= sample mean of differences