Zeller's congruence

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Zeller's congruence is an algorithm devised by Christian Zeller to calculate the day of the week for any Julian or Gregorian calendar date.

Contents |

[edit] Formula

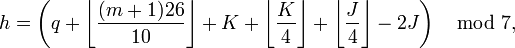

For the Gregorian calendar, Zeller's congruence is

for the Julian calendar it is

where

- h is the day of the week (0 = Saturday, 1 = Sunday, 2 = Monday, ...

- q is the day of the month

- m is the month (3 = March, 4 = April, 5 = May, ...)

- K the year of the century (

).

). - J is the century (actually

) (For example, in 1995 the century would be 19, even though it was the 20th century.)

) (For example, in 1995 the century would be 19, even though it was the 20th century.)

NOTE: In this algorithm January and February are counted as months 13 and 14 of the previous year.

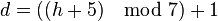

For an ISO week date Day-of-Week d (1 = Monday to 7 = Sunday), use

[edit] Implementation in software

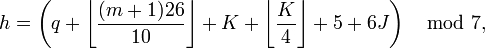

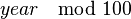

The formulas rely on the mathematician's definition of modulo division, which means that −2 mod 7 is equal to positive 5. Unfortunately, the way most computer languages implement the remainder function, −2 mod 7 returns a result of -2. So, to implement Zeller's congruence on a computer, the formulas should be altered slightly to ensure a positive numerator. The simplest way to do this is to replace − 2J by + 5J and − J by + 6J. So the formulas become:

for the Gregorian calendar, and

for the Julian calendar.

One can readily see that, in a given year, March 1 (if that is a Saturday, then March 2) is a good test date; and that, in a given century, the best test year is that which is a multiple of 100.

Zeller used decimal arithmetic, and found it convenient to use J & K in representing the year. But when using a computer, it is simpler to handle the modified year Y by using Y, Y div 4, and for Gregorian also Y div 100 & Y div 400.

[edit] Analysis

These formulas are based on the observation that the day of the week progresses in a predictable manner based upon each subpart of that date. Each term within the formula is used to calculate the offset needed to obtain the correct day of the week.

For the Gregorian calendar, the various parts of this formula can therefore be understood as follows:

- q represents the progression of the day of the week based on the day of the month, since each successive day results in an additional offset of 1 in the day of the week.

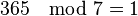

- K represents the progression of the day of the week based on the year. Assuming that each year is 365 days long, the same date on each succeeding year will be offset by a value of

.

.

- Since there are 366 days in each leap year, this needs to be accounted for by adding an additional day to the day of the week offset value. This is accomplished by adding

to the offset. This term is calculated as an integer result. Any remainder is discarded.

to the offset. This term is calculated as an integer result. Any remainder is discarded.

- Using similar logic, the progression of the day of the week for each century may be calculated by observing that there are 36524 days in a normal century and 36525 days in each century divisible by 400. Since

and

and  , the term :

, the term : accounts for this (again using integer division and discarding any fractional remainder). To avoid negative numbers, this term can be replaced with :

accounts for this (again using integer division and discarding any fractional remainder). To avoid negative numbers, this term can be replaced with : with equivalent results.

with equivalent results.

- The term

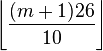

can be explained as follows. Zeller observed that, by starting each year on March 1, the day of the week for each succeeding month progressed by multiplying the month by a constant value and discarding the fractional remainder.

can be explained as follows. Zeller observed that, by starting each year on March 1, the day of the week for each succeeding month progressed by multiplying the month by a constant value and discarding the fractional remainder.

- The overall function,

, normalizes the result to reside in the range of 0 to 6, which yields the index of the correct day of the week for the date being analyzed.

, normalizes the result to reside in the range of 0 to 6, which yields the index of the correct day of the week for the date being analyzed.

The reason that the formula differs for the Julian calendar is that this calendar does not have a separate rule for leap centuries and is offset from the Gregorian calendar by a fixed number of days each century.

Since the Gregorian calendar was adopted at different times in different regions of the world, the location of an event is significant in determining the correct day of the week for a date that occurred during this transition period.

The formulae can be used proleptically, but with care for years before Year 0. To accommodate this, one can add a sufficient multiple of 400 Gregorian or 28 Julian years.

[edit] Examples

For January 1, 2000, the date would be treated as the 13th month of 1999, so the values would be:

- q = 1

- m = 13

- K = 99

- J = 19

So the formula evaluates as (1 + 36 + 99 + 24 + 4 − 38) mod 7 = 126 mod 7 = 0 = Saturday

(The 36 comes from (13+1)*26/10 = 364/10, truncated to an integer.)

However, for March 1, 2000, the date is treated as the 3rd month of 2000, so the values become

- q = 1

- m = 3

- K = 0

- J = 20

so the formula evaluates as (1 + 10 + 0 + 0 + 5 − 40) mod 7 = −24 mod 7 = 4 = Wednesday

[edit] See also

[edit] References

Each of these four similar imaged papers deals firstly with the day of the week and secondly with the date of Easter Sunday, for the Julian and Gregorian Calendars. The pages link to translations into English.

- Zeller, Christian (1882). "Die Grundaufgaben der Kalenderrechnung auf neue und vereinfachte Weise gelöst" (in German). Württembergische Vierteljahrshefte für Landesgeschichte V: 313–314. http://www.merlyn.demon.co.uk/zel-82px.htm.

- Zeller, Christian (1883). "Problema duplex Calendarii fundamentale" (in Latin). Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France 11: 59–61. http://www.merlyn.demon.co.uk/zel-83px.htm.

- Zeller, Christian (1885). "Kalender-Formeln" (in German). Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Mitteilungen des mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins in Württemberg 1 (1): 54–58. http://www.merlyn.demon.co.uk/zel-85px.htm.

- Zeller, Christian (1886). "Kalender-Formeln" (in German). Acta Mathematica 9: 131–136. doi:. http://www.merlyn.demon.co.uk/zel-86px.htm.

[edit] External links

- The Calendrical Works of Rektor Chr. Zeller: The Day-of-Week and Easter Formulae by J R Stockton, near London, UK. The site includes images and translations of the above four papers, and of Zeller's reference card "Das Ganze der Kalender-Rechnung".

- This article incorporates text from the NIST Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures, which, as a U.S. government publication, is in the public domain. Source: Zeller's congruence.