Knapsack problem

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

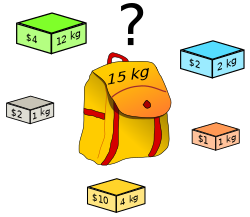

(Solution: if any number of each box is available, then three yellow boxes and three grey boxes; if only the shown boxes are available, then all but the green box.)

The knapsack problem or rucksack problem is a problem in combinatorial optimization. It derives its name from the following maximization problem of the best choice of essentials that can fit into one bag to be carried on a trip. Given a set of items, each with a weight and a value, determine the number of each item to include in a collection so that the total weight is less than a given limit and the total value is as large as possible.

A similar problem often appears in business, combinatorics, complexity theory, cryptography and applied mathematics.

The decision problem form of the knapsack problem is the question "can a value of at least V be achieved without exceeding the weight W?"

Contents |

[edit] Definition

In the following, we have n kinds of items, 1 through n. Each kind of item j has a value pj and a weight wj. We usually assume that all values and weights are nonnegative. The maximum weight that we can carry in the bag is W.

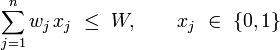

The 0-1 knapsack problem restricts the number xj of copies of each kind of item to zero or one. Mathematically the 0-1-knapsack problem can be formulated as:

- maximize

- subject to

The bounded knapsack problem restricts the number xj of copies of each kind of item to a maximum integer value bj. Mathematically the bounded knapsack problem can be formulated as:

- maximize

- subject to

The unbounded knapsack problem places no upper bound on the number of copies of each kind item.

Of particular interest is the special case of the problem with these properties:

- it is a decision problem,

- it is a 0-1 problem,

- for each kind of item, the weight equals the value: wj = pj.

Notice that in this special case, the problem is equivalent to this: given a set of nonnegative integers, does any subset of it add up to exactly W? Or, if negative weights are allowed and W is chosen to be zero, the problem is: given a set of integers, does any subset add up to exactly 0? This special case is called the subset sum problem. In the field of cryptography the term knapsack problem is often used to refer specifically to the subset sum problem.

[edit] Computational complexity

The knapsack problems are often solved using dynamic programming, though no polynomial-time algorithm is known. Both the knapsack problem(s) and the subset sum problem are NP-hard, and this has led to attempts to use subset sum as the basis for public key cryptography systems, such as Merkle-Hellman. These attempts typically used some group other than the integers. Merkle-Hellman and several similar algorithms were later broken, because the particular subset sum problems they produced were in fact solvable by polynomial-time algorithms.

The decision version of the knapsack problem described above ("can a value of at least V be achieved without exceeding the weight W?") is NP-complete. The subset sum version of the knapsack problem is commonly known as one of Karp's 21 NP-complete problems.

The knapsack problem with each type of item j having a distinct value per unit of weight (vj = pj/wj) is considered one of the easiest NP-complete problems. Indeed empirical complexity is of the order of O((log n)2) and very large problems can be solved very quickly, e.g. in 2003 the average time required to solve instances with n = 10,000 was below 14 milliseconds using commodity personal computers[1]. However in the degenerate case of multiple items sharing the same value vj it becomes much more difficult with the extreme case where vj = constant being the subset sum problem with a complexity of O(2N/2N).

[edit] Dynamic programming solution

[edit] Unbounded knapsack problem

If all weights (w1, ..., wn and W) are nonnegative integers, the knapsack problem can be solved in pseudo-polynomial time using dynamic programming. The following describes a dynamic programming solution for the unbounded knapsack problem.

To simplify things, assume all weights are strictly positive (wj > 0). We wish to maximize total value subject to the constraint that total weight is less than or equal to W. Then for each Y ≤ W, define A(Y) to be the maximum value that can be attained with total weight less than or equal to Y. A(W) then is the solution to the problem.

Observe that A(Y) has the following properties:

- A(0) = 0 (the sum of zero items, i.e., the summation of the empty set)

- A(Y) = max { pj + A(Y − wj) | wj ≤ Y }.

Here the maximum of the empty set is taken to be zero. Tabulating the results from A(0) up through A(W) gives the solution. Since the calculation of each A(Y) involves examining n items, and there are W values of A(Y) to calculate, the running time of the dynamic programming solution is O(nW). Dividing w1, ..., wn, W by their greatest common divisor is an obvious way to improve the running time.

The O(nW) complexity does not contradict the fact that the knapsack problem is NP-complete, since W, unlike n, is not polynomial in the length of the input to the problem. The length of the input to the problem is proportional to the number, log W, of bits in W, not to W itself.

An improved version of the dynamic programming algorithm named EDUK is presented in [2]. It uses a sparse representation of the search space, introduces a new dominance relation between items and takes advantage of the periodicity property of the problem which states that beyond a certain capacity, the only item that contributes is the best one(the one with the best profit.weight ratio), that property was first described by Gilmore and Gomory[3]

[edit] 0-1 knapsack problem

A similar dynamic programming solution for the 0-1 knapsack problem also runs in pseudo-polynomial time. As above, assume w1, ..., wn, W are strictly positive integers. Define A(j, Y) to be the maximum value that can be attained with weight less than or equal to Y using items up to j.

We can define A(j,Y) recursively as follows:

- A(0, Y) = 0

- A(j, 0) = 0

- A(j, Y) = A(j − 1, Y) if wj > Y

- A(j, Y) = max { A(j − 1, Y), pj + A(j − 1, Y − wj) } if wj ≤ Y.

The solution can then be found by calculating A(n, W). To do this efficiently we can use a table to store previous computations. This solution will therefore run in O(nW) time and O(nW) space, though with some slight modifications we can reduce the space complexity to O(W).

[edit] Greedy approximation algorithm

George Dantzig proposed (1957) a greedy approximation algorithm to solve the unbounded knapsack problem. His version sorts the items in decreasing order of value per unit of weight, pj/wj. It then proceeds to insert them into the sack, starting with as many copies as possible of the first kind of item until there is no longer space in the sack for more. Provided that there is an unlimited supply of each kind of item, if A is the maximum value of items that fit into the sack, then the greedy algorithm is guaranteed to achieve at least a value of A/2. However, for the bounded problem, where the supply of each kind of item is limited, the algorithm may be very much further from optimal.

[edit] Hybrid algorithm for the Unbounded Knapsack Problem

Poirriez et al. proposed (2008) [4]an hybrid algorithm to solve the unbounded knapsack problem. Their algorithm takes advantage of all the known properties of the problem (at this date). Namely, it uses a sparse dynamic programming algorithm like EDUK with the known dominance relations between items, and hybrid it with bounds computation within a Branch and bound scheme. A new upper bound is brought to the fore and a sub-family of instances is distinguished. The so called SAW-UKP family includes the strong correlated instances.

[edit] See also

- Branch and bound - a method applicable to n-dimensional knapsack problems

- List of knapsack problems

- Packing problem

- Bin packing problem

- Cutting stock problem

[edit] References

- ^ Pisinger, D. 2003. Where are the hard knapsack problems? Technical Report 2003/08, Department of Computer Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- ^ Andonov,R., Poirriez,V.,Rajopadhye, S. 2000 . Unbounded Knapsack Problem : dynamic programming revisited. European Journal of Operational Research Volume 123, Issue 2, 1 June 2000, Pages 394-407. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.disopt.2008.09.004

- ^ Gilmore,P.C. and Gomory, R.E. The theory and computation of Knapsack Functions. Operations Research 14:1045-1075, 1966.

- ^ Poirriez V., Yanev N., Andonov R. A Hybrid Algorithm for the Unbounded Knapsack Problem. Discrete Optimization Volume 6, Issue 1, February 2009, Pages 110-124 Elsevier

[edit] Further reading

- Garey, Michael R.; David S. Johnson (1979). Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-1045-5. A6: MP9, pg.247.

- Martello, Silvano; Paolo Toth (1990). Knapsack Problems: Algorithms and Computer Implementations. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-92420-2.

- Kellerer, Hans; U. Pferschy, D. Pisinger (2005). Knapsack Problems. Springer Verlag. ISBN 3-540-40286-1.

- Poirriez, Vincent; N.Yanev,R.Andonov (2009). A Hybrid Algorithm for the Unbounded Knapsack Problem. Elsevier. doi:.

[edit] External links

- Lecture slides on the knapsack problem

- PYAsUKP: Yet Another solver for the Unbounded Knapsack Problem, with code, benchmarks and downloadable copies of some papers.

- Home page of David Pisinger with downloadable copies of some papers on the publication list (including "Where are the hard knapsack problems?")